Recent evidence has linked obesity and the metabolic syndrome with gut dysbiota. The precise mechanisms underlying that association are not entirely understood; however, microbiota can enhance the extraction of energy from diet and regulate whole-body metabolism towards increased fatty acids uptake from adipose tissue and shift lipids metabolism from oxidation to de novo production. Obesity and high fat diet relate to a specific gut microbiota, which is enriched in Firmicutes and with less Bacterioidetes. Microbiota can also play a role in the development of hepatic steatosis, necroinflammation and fibrosis. In fact, some studies have shown an association between small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, increased intestinal permeability and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). That association is, in part, due to increased endotoxinaemia and activation of the Toll-like receptor-4 signaling cascade. Preliminary data on probiotics suggest a potential role in NASH treatment, however randomized controlled clinical trials are still lacking.

There are more microbes in the gut than cells in the human body. The human gut hosts about 1.5 kg i.e. one hundred trillion commensal organisms, hundreds to thousands of different species. Also, the gut microbiota genome includes 200,000-300,000 genes, ten times more that of the human genome.1 This permissive overcrowding most certainly comes with some compensation to the host. Those guests have been subjected to selection pressure long before humans have arrived on this planet, and hosting those organisms allow us to take advantage of 400 million years of experience.

The commensal organisms that populate the human gut are dominated by four main phyla: Firmi-cutes, Bacterioidetes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria.2 Firmicutes is the main bacterial phylum, comprising more than 250 genera, such as Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma and Clostridium.3They are able to produce several short chain fatty acids (SCFA) like butyrate.2 Bacterioide-tes is a phylum that includes 20 genera, the most abundant of which is Bacteroides (thetaiotaomi-cron).3 They are able to produce hydrogen.

The liver is in close anatomical and functional connection with the gut, through portal circulation, favoring bidirectional influences. Recent evidence has linked microbiota to obesity, insulin resistance and steatosis, issues that will be approached in this review.

Gut Microbiota and ObesityThe regulation of body weight depends on subtle mechanisms, and mild changes, as little as a 1% increase in daily calorie intake, may have important consequences in the long run.4

The first evidence that gut microbiota may interfere with body weight and composition comes from Backhed, et al.5 They analyzed germ free mice and conventionally raised mice that were allowed to acquire gut microbiota from birth to adulthood.5 Conventional mice presented more adipose tissue and a higher percentage of body fat, compared to germ free mice, although eating less amounts of the same diet. Mice hosting gut microbiota also presented higher levels of leptin, an orexigenic adipokine, and insulin resistance, with increased fasting blood glucose and insulin. They went further and transplanted normal microbiota harvested from the distal intestine (caecum) of conventionally raised mice into adult germ free mice, resulting in a 57% increase in body fat content and insulin resistance within just 14 days. Those changes were associated with decreased intestinal expression of fasting induced adipose factor (Fiaf), also known as angiopoietin-like factor IV, a circulating lipoprotein lipase inhibitor, thus favoring fatty acid uptake and adipose tissue expansion. Fiaf also induces peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) coactivator 1 (PGC-1α) that regulates the expression of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation.6 In fact, germ free Fiaf -/knock out (ko) mice have the same amount of body fat as conventional mice.5 Fiaf may thus be seen as a mediator in the microbial regulation of the peripheral fat reservoir.

Later on, the same authors showed that, unlike conventionally raised mice, germ free mice did not increase their weight when exposed to a high fat, high carbohydrate diet.6 Diet alone was not sufficient to induce obesity. Germ free mice not only presented higher circulating Fiaf levels, they also presented increased skeletal muscle and liver levels of phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its downstream targets involved in fatty acid oxidation (acetyl-CoA carboxylase and car-nitine palmitoyltransferase).6

Not only the presence of intestinal microbiota, but also its composition may influence body fat. Obesity seems to be associated with a specific microbiome that is able to extract more energy from the diet.7 Turnbaugh and colleagues showed that genetically obese mice (ob/ob) wasted less energy in the stools compared with lean mice. On the other hand, obese mice presented higher caecal SCFA content, acetate and butyrate, end products of bacterial carbohydrate fermentation. Finally, they transplanted germ free mice with caecal microbiota from both lean and obese mice. When the donor was an obese mouse, germ free mice gained much more weight and acquired higher efficiency in extracting calories from their diet than they did when the donor was a lean mouse. In other words, the obese phenotype could be transmissible by the microbiota.7

It was Ley who first showed differences in the mi-crobiota of the obese.8 In fact, as compared to lean mice, genetically obese mice (ob/ob) presented a 50% decrease in Bacterioidetes and a similar increase in Firmicutes content, which is associated with enrichment of the glycoside hydrolases that break down indigestible dietary polysaccharides, transport proteins importing the breakdown products and enzymes generating end products such as butyrate and acetate. Obese mice also presented an increase in methanogenic Archaea, which is associated with a lower hydrogen partial pressure, thereby optimizing bacterial fermentation rates. Those changes in mi-crobiota can explain why obese mice present an increased capacity to harvest energy from the diet.8 Similar results were found in a mouse model of Western-diet induced obesity.9 The increase in Firmicu-tes was in a particular class, Mollicutes.10

Studies in humans mimicked the same changes in microbiota with obesity and a high fat diet. A large study with 154 subjects (adult female monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs concordant for leanness or obesity, and their mothers) showed that the human intestinal microbiome is shared by family members, but is specific for each individual. However it is of interest that there was a comparable degree of co-variation between adult monozygotic and dizygo-tic twin pairs, which is suggestive of there being no genetic inheritance.11 Also, obesity was associated with decreased bacterial diversity, decreased Bacte-rioidetes and increased Actinobacteria, although with no differences regarding Firmicutes content. Furthermore, obesity presented different bacterial genes and metabolic pathways.11 The same group carried out an experiment that consisted of transplantation of human feces to germ free mice. When humanized mice were switched from a low-fat plant rich diet to a high-fat, high-sugar diet, the microbio-ta changed in just 24 h. Western diet fed humanized mice became obese, and that phenotype could be transmitted to other mice by transplanting their gut microbiota to germ-free recipients.12 A different approach, with similar results, was a study with obese patients submitted to weight loss intervention with different diets, with restriction of carbohydrate or fat.13 Weight loss paralleled a decrease in Firmi-cutes and increase in Bacterioidetes content. Of note, the increase in Bacterioidetes occurred earlier in the carbohydrate-restricted rather than fat-restricted diet, above a threshold of 2% vs. 6% weight loss.13 Finally, obese patients submitted to bariatric bypass surgery changed their gut microbiota, with a decrease in Firmicutes and Archaea content.14 Another interesting concept is that differences in gut intestinal microbiota may precede obesity. Two pediatric studies, which collected fecal samples from infants 3 to 12 months old, and prospectively followed them up for seven to ten years, showed that children that became obese initially presented lower numbers of Bacterioidetes, Bifidobacterium and higher numbers of Staphylococcus aureus.15,16

Commensal microbiota is related not only to obesity, but also to its co-morbidities, such as diabetes mellitus. As with obese patients, diabetics present different microbiota composition.17–19 Modulation of microbiota with antibiotics, norfloxacin and ampici-llin, improves glucose-tolerance in diet-induced obese mice independently of diet intake or adiposity.20

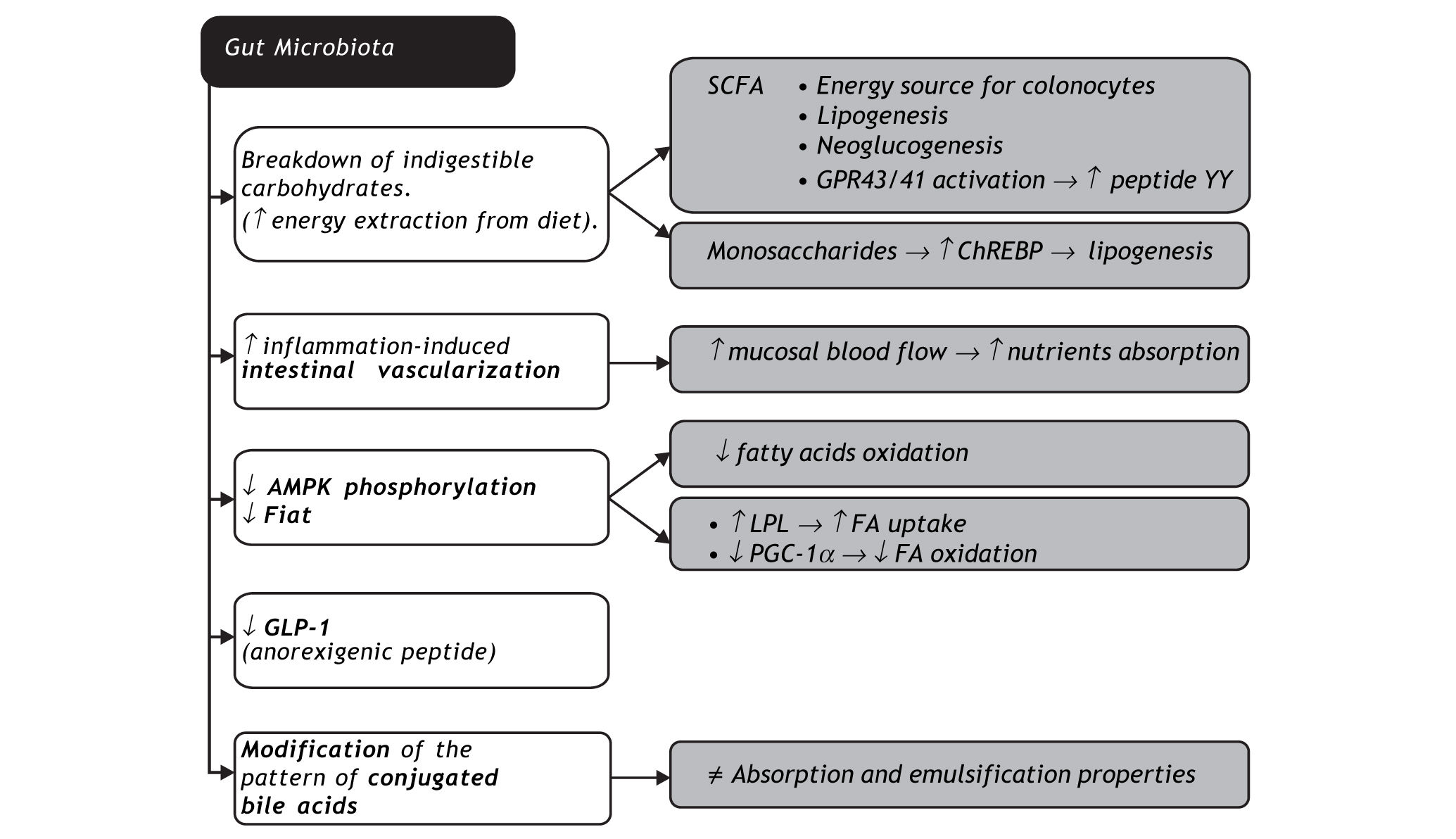

Gut microbiota may promote obesity through several mechanisms. The first is the possibility of fermenting otherwise indigestible carbohydrates in SCFA and monosaccharide. SCFA are not only substrates of colonocytes, they are also cholesterol or fatty acid precursors, and neoglucogenesis substrates in the liver, with higher exploitation of diet energy. SCFA bind to specific receptors in intestinal endocrine cells (GRP43 and GRP41) that lead to an increase in peptide YY, slowing down bowel transit, thereby allowing a higher nutrient absorption rate21 and increase in leptin, an orexigenic hormone.22 Increased liver monosaccharide uptake from portal circulation activates key transcription factors such as carbohydrate responsive element binding protein (ChREBP), which regulates lipogenesis.23 Microbio-ta also increases inflammation-induced vasculariza-tion and blood flow in the mucosa, enhancing nutrient absorption.24 The ability of commensal micro-organisms to decrease Fiaf and AMPK phos-phorylation has already been addressed in this review. Intestinal dysbiosis is also associated with decreased intestinal glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) expression, an anorexigenic peptide.25 Finally, intestinal microbiota modifies the pattern of conjugated bile acids, with direct impact on their absorption and emulsification properties.26

Gut Microbiota and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseaseRegarding the potential interaction between gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NA-FLD) there is evidence from the work of Backhed and collaborators that transplanting normal micro-biota harvested from the distal intestine (caecum) of conventionally raised mice into germ free mice not only increased body fat, it also specifically increased liver fat.5 The authors also demonstrated a greater than two-fold increase in liver triglyceride content, associated with a higher monosaccharide absorption from the lumen, promoting de novo fatty acid synthesis, as confirmed by an increased acetyl-CoA car-boxylase activity and fatty acid synthase.5

NAFLD and steatohepatitis have been associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and increased intestinal permeability. In fact, a short time after its description, nonalcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH) was reported in patients with SIBO after intestinal bypass, which reverted after a metronidazol trial or after resection of the bypassed bowel segment.27 NASH has also been reported in patients with SIBO associated with small bowel di-verticulosis.28

Animal models with SIBO have been associated with NASH histology, which reverts after antibiotic therapy.29,30

Wigg, et al. studied 23 patients with NASH and 23 healthy controls and evaluated the presence of SIBO with 14C-D-xylose and lactulose breath test.31 They found SIBO in 50% of NASH patients as opposed to 22% in controls. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels were also increased in NASH patients. However, they failed to demonstrate increased endotoxaemia or disturbed intestinal permeability. Some limitations were pointed out, namely the lack of a group with simple steatosis, and the definition of NASH requiring only macrovesicular steatosis and inflammation on liver histology, the presence of ballooned hepatocytes not being necessary. The assessment of intestinal permeability was restricted to the small bowel. Furthermore, the methodology used has low sensitivity and specificity.32 Posterior studies also suggested an association between SIBO and NASH33 or severity of hepatic steatosis.34,35 In fact, Miele. et al. evaluated intestinal permeability with 51Cr-EDTA (ethylene dia-mine tetra-acetate) in 35 patients with histologicallyconfirmed NAFLD, 27 celiac patients and 24 healthy controls. Intestinal permeability correlated with hepatic steatosis severity, although not with the presence of NASH. Also, severe steatosis correlated with altered tight junction integrity, as assessed by immunohisto-chemistry studies for zonula-occludens-1 (ZO-1) carried out on duodenal samples.

On the other hand, Farhadi, et al.36 found no difference in baseline intestinal permeability between NASH patients and controls when using urinary excretion of 5-h lactulose/mannitol (L/M) ratio and 24-h sucralose. Nonetheless, aspirin more frequently triggered increased whole-gut permeability in NASH patients, thus suggesting an increased susceptibility to intestinal leakiness. Dysbiosis-related decrease in glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2), an endogenous intestinotrophic, further contributes to disturbed tight junction integrity and increased intestinal permeability.25

Several bacterial bioproducts may be potentially hepatotoxic e.g. ammonia, phenols, ethanol, among others.37 Increased intestinal production of ethanol has been described in obese patients.38 Also, treatment with antibiotics decreases intestinal ethanol production.33,39 The main bacterial bioproduct that is likely to be involved in NAFLD/NASH pathogene-sis is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the active component of endotoxin, an element of the cell wall of Gram negative bacteria. Endogenous LPS is continuously produced in the gut with bacterial death. Its translocation through intestinal capillaries occurs in a toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4)-dependent mechanism. From there, LPS transport to target tissues is facilitated by lipoproteins, chylomicra, synthesized by enterocytes in response to fat in the diet.40 In fact, LPS absorption occurs during lipid absorption.41 LPS binds to lipopolysaccharide binding-protein (LBP), and that complex binds to CD14, expressed in inflammatory cells, enterocytes or in a soluble form. Together, LPS-LBP-CD14, activate TLR-4, present in inflammatory cells like mo-nocytes, Kupffer cells and even stellate cells. An intracellular cascade is triggered, including stress-activated and mitogen-activated kinases, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and interferon-regulatory factor-3 (IFR-3). NFκB translocates to the nucleus where it enhances the expression of several target genes involved in the inflammatory pathway, such as TNF-α, interleukin 1 and 6.37 TLR-4 signaling can thus promote insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fi-brogenesis.

Cani, et al. exposed mice to a high-fat diet, producing a two-to three-fold increase in LPS plasma levels, inducing what has been called metabolic en-dotoxaemia, as opposed to endotoxaemia in septic shock, in which LPS levels are 10-50 times higher.42 Also, chronic infusion of low LPS doses in mice mimicked the high-fat diet phenotype, causing obesity and increase in fat body weight percentage, insulin resistance, adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, CD14 -/- ko mice were protected from those metabolic consequences, either after LPS infusion, or with a high-fat diet. Similarly, TLR-4 -/- ko mice are protected from steatosis/NASH development with a methionine-choline deficient (MCD) diet, an animal model of NASH.43 Also, genetically obese, fa/fa and ob/ob, mice are more susceptible to endotoxin hepatotoxici-ty, rapidly developing NASH after exposure to low doses of LPS,44 which may be explained by Kupffer cell dysfunction with decreased phagocytic potential, decreasing the barrier to the passage of LPS from portal to systemic circulation, and thus increasing extrahepatic cytokine production.44 In the same way, in MCD-diet and high-fat diet mice, LPS induces more TNF-a expression, hepatocyte apoptosis and death than in mice on a standard diet.45,46

Human studies have also demonstrated that endo-toxaemia is a risk factor for NAFLD and NASH development. Two studies with biopsy-proven NAFLD patients showed increased endotoxaemia in comparison with healthy controls.47,48 Endotoxaemia was even higher in NASH patients compared to patients with simple steatosis.49 Endotoxin plasma levels also correlated positively with insulin resistance.48 More recently, Verdam, et al. studied severely obese patients, and showed that patients with NASH presented higher IgG antibody anti-endotoxin titres than patients with healthy livers. Furthermore, those antibody titres progressively increased according to severity of hepatic inflammation.50

In short, several mechanisms may explain the potential steatogenic and pro-inflammatory effect of intestinal microbiota. It promotes an increase in free fatty acid uptake and production by the liver, as previously explained. On the other hand, an increase in LPS, through activation of TLR-4 inflammatory signaling cascade, leads to insulin resistance and TNF-α mediated inflammation, as well as hepatic fibrogene-sis, since stellate cells express those receptors.37 Among other potentially steatogenic and pro-inflammatory bacterial bioproducts is ethanol. Disturbance in choline metabolism is another important mechanism. Microbiota produces enzymes that catalyze the first step in the conversion of diet-derived choli-ne into dimethylamine and trimethylamine.51 That can have two important consequences in the liver: the uptake of those hepatotoxic substances52 and choline depletion.53 Choline is necessary to the VLDL assembly and to lipid export from the liver.44 In that way, microbiota promotes hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance and lipoperoxidation injury.53,54 Lastly, by changing the bile acid pattern, microbiota can indirectly promote hepatic steatosis and lipope-roxidation, through signaling pathway cascades responsive to bile acids, such as farsenoid X receptor (FXR) stimulation.26,55

Fructose, Gut Microbiota and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseaseFructose monosaccharide intake has been increasing extraordinarily in recent decades, mostly associated with high fructose corn syrup, primarily in the form of soft drinks.56 The liver is the main site of fructose metabolism, since it possesses Glut-5, the specific receptor.57 Fructose is different from glucose, since its metabolism is insulin-independent and is more prone to promote de novo lipogenesis and stimulate triglyceride synthesis.58 It is also more prone to induce obesity, since it may not cause the level of satiety equivalent to that of a glucose-based meal,59 besides slowing down the basal metabolic rate.60

Animal models have already demonstrated an association between fructose and hepatic steatosis, NASH and even hepatic fibrosis development.61–63 Recently it has been shown that in humans, high fructose consumption also increases the risk of developing NAFLD.56 It is also associated with disease severity, namely hepatic inflammation and more advanced fibrosis.64

An association between fructose and several risk factors of NAFLD/NASH is well known. For instance, it is associated with arterial hypertension through indirect inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase caused by an increase in uric acid.58 Also, insulin requires nitric oxide to stimulate glucose uptake contributing to insulin resistance,65 besides having an indirect action in the insulin cascade signaling through increased intracellular diacylgly-cerol. Fructose also is known to be a risk factor for the development of the full metabolic syndrome, not only its individual components.66 Nakagawa, et al. showed that mice fed on a high fructose diet, unlike those on a high dextrose diet, developed metabolic syndrome.65 Interestingly, co-treatment with allopu-rinol (a xanthine oxidase inhibitor) or benzbromarone (a uricosuric agent) was able to prevent or reverse features of the metabolic syndrome, like hyperinsuli-nemia, systolic hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia and weight gain.65 Studies in humans confirmed the association between fructose consumption and metabolic syndrome.

Not until recently was it proposed that the link between fructose consumption and hepatic steatosis is an increase in SIBO and disturbed intestinal per-meability.67 Bergheim at al. submitted mice to a diet either with a solution with 30% glucose, 30% fructose, 30% sucrose or water with an artificial sweetener.68 They found that despite the fact that mice exposed to glucose had a higher caloric intake and increased weight, fructose exposed mice developed more hepatic steatosis, and that was associated with increased portal blood LPS levels and TNF-α production. Also, co-treatment with antibiotics (polymyxin B and neomycin) prevented steatosis development in fructose-fed mice. In another experiment, co-treatment with a prebiotic, oligofructose, prevented hy-pertriglyceridemia and liver damage associated with a high-fructose diet.69 Lastly, TLR-4 mutant mice are resistant to hepatic steatosis, TNF-α induction, lipid peroxidation and insulin resistance, as compared to wild type mice.67 Studies in humans also showed that fructose intake was associated not only with NAFLD but also with an increase in endotoxaemia and hepatic expression of TLR-4.47 It is not yet understood what the mechanisms are that lead to bacterial overgrowth and increased intestinal permeability. However, bacterial flora can ferment carbohydrates to alcohol when intestinal stasis allows their overgrowth in the upper parts of the gastrointestinal tract.70 A recent report has also suggested that fructose consumption is associated with the activation of serotonin reuptake transporters, which regulate intestinal motility and permeability.71

Approach to Gut Microbiota as a Therapeutic Tool in the Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseaseWe can interfere with gut microbiota through the use of several types of compounds: probiotics, pre-biotics and symbiotics. Probiotics are live commensal micro-organisms that are able to modulate the intestinal microbiota with benefits to the host’s health. The most common probiotics in the market are Lactobacilli, Streptococci and Bifidobacteria. Prebiotics are indigestible carbohydrates that stimulate the growth and activity of beneficial bacteria, particularly Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria. Some examples of prebiotics are lactulose, which increases the number of Bifidobacteria, and fructooligosaccha-rides like oligofructose and inulin. Lastly, symbiotics are products that contain both probiotics and prebio-tics, like a combination of inulin, Lactobacillus rhamnosus G and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12.72

Despite numerous papers in this area, it is difficult to access the true effect of probiotics on NAFLD prevention or treatment, since the experiments made use of different animal models and different bacterial strains. The most frequently used probiotic is VSL#3, a mixture of different bacteria (Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobac-terium longum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus bulgaricus). Li, et al.73 studied the effect of VSL#3, given for four weeks, on ob/ob mice submitted to a high fat diet. VSL#3 improved liver histology, reduced total hepatic fatty acids content, decreased aminotransfe-rase plasma levels, and downregulated pro-inflammatory JNK and NFκB pathways. Similar effects were accomplished with the administration of anti-TNF-α antibody. In another paper, VSL#3 was able to improve insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in mice on a high fat diet.74 Those effects were believed to be the consequence of immune regulation. The authors showed that high fat diet induced natural killer T (NKT) cell depletion, which occurs earlier than insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Probiotics were able to prevent NKT cell depletion, and metabolic benefits were dependent on the latter. In fact, similar effects are achieved when NKT cells are transferred from normal controls. Also, probio-tics were not effective in mice without NKT cells. Others corroborated the effect of VSL#3 in improving inflammation, oxidative stress and fibrogenesis in a high-fat diet or MCD diet fed mice.75,76

In relation to prebiotics, Fan et al. showed that lactulose decreased hepatic inflammation and portal vein LPS levels in rats with high fat diet induced NASH.77 Several animal models of NAFLD also suggested a beneficial effect of oligofructose in preventing hepatic steatosis development.78–80

Regarding studies with probiotics in humans, there are only two pilot studies.81,82 The first study included 10 patients with biopsy proven NASH in whom a symbiotic (Lactobacillus acidophilus, bifidus, rhamnosus, plantarum, salivarius, bulgaricus, lactis, casei, breve and the prebiotic fructooligosaccharide with vitamins) was administered for two months.81

The second looked at 22 patients with NAFLD in whom VSL#3 was administered for three months.82 Both showed improvement of aminotransferases, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, TNF-α and oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxinone-nal, while on treatment. A meta-analysis83 concluded that this preliminary data indicate that probiotics are well tolerated, may improve liver tests and markers of lipid peroxidation, suggesting a possible therapeutic role. However, randomized controlled clinical trials would be needed before such compounds could be recommended as treatment.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, intestinal microbiota may influence body composition, favoring the expansion of adipose tissue, contributing to the obesity pandemic. Obese subjects have a specific microbiota that harvest energy from the diet more effectively, producing more SCFA and decreasing Fiaf expression, leading to greater entry of fatty acids into peripheral adipose tissue and the liver. Also, diet itself, specifically high fat and fructose consumption, is known to modulate intestinal microbiota leading to metabolic endotoxaemia. Endotoxaemia promotes the development of insulin resistance, steatosis, inflammation and hepatic fibrogenesis. However the correlation between steatosis severity and presence or absence of NASH with the degree of intestinal permeability and/or endotoxinaemia has not shown uniform results among studies.

Recently, it has been shown that hepatic steatosis and NASH are associated with bacterial proliferation and increased intestinal permeability, so it would be expected that interventions that modulate intestinal microbiota may be beneficial in the prevention or even treatment of those conditions. However, studies in animal models are difficult to evaluate since they use different models, different bacterial strains and different doses. There are only two pilot studies in humans of probiotic treatment in patients with NAFLD and NASH, and they suggest a potential role for modulation of gut microbio-ta. However, randomized clinical trials are needed before any recommendation can be made.

Abbreviations- •

SCFA: short chain fatty acids.

- •

Fiaf: fasting induced adipose factor.

- •

PPARγ: peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor gamma

- •

PGC-lα: peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor coactivator.

- •

ko: knock out.

- •

AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase.

- •

ChREBP: carbohydrate responsive element binding protein.

- •

GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1.

- •

NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

- •

SIBO: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

- •

NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

- •

TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha.

- •

51Cr-EDTA: ethylene diamine tetra-acetate.

- •

ZO-1: zonula-occludens-1.

- •

GLP-2: glucagon-like peptide 2.

- •

LPS: lipopolysaccharide.

- •

TLR-4: toll-like receptor-4.

- •

LBP: lipopolysaccharide binding-protein.

- •

JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

- •

NFκB, nuclear factor κB.

- •

IRF-3: interferon-regulatory factor-3.

- •

MCD: methionine-choline deficient.

- •

FXR: farsenoid X receptor.

- •

NKT cells: natural killer T cells.