Introduction. Response to hepatitis C treatment is known to differ by race; and, limited data suggests by ethnicity as well. A lower efficacy of HCV therapy in Latinos has been observed; whether higher doses may improve the response is unknown.

Material and methods. This study used the available data from the patients enrolled in the PROGRESS study and stratified it by race and ethnicity. The primary objectives were to evaluate the early viral kinetic pattern in Latino patients and to assess whether it was improved by higher doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a and/or RBV, as compared to Caucasian and African American patients.

Results. From a total of 1145 patients, 51 (4%) were classified Latino, 886 (77%) Caucasian, 124 (11%) African American and 84 (7%) other. Latinos had a similar virological response between the treatment groups at week 4; but by week 12, achieved a greater response with the higher intensified dose of peginterferon alfa-2a, and remained so at week 72. Caucasians had a greater response at week 4 and week 12 with the intensified dose; but by week 72, the response became similar between the treatment groups. The virological responses for African Americans were unaffected by the doses; and by week 12, were lower than both Latinos and Caucasians. In conclusion, this retrospective analysis provides further evidence for racial/ethnic differences in the response to peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin therapy in patients with HCV. Although the sample sizes in this analysis are small for generalized conclusions, the findings are of importance to physicians treating Latinos.

Race is one of several factors that have shown an impact on the therapeutic response to chronic hepatitis C treatment (CHC).1–4 Ethnicity may also have an impact on response;5 however, data is limited since ethnic and racial subpopulations have been underrepresented in the large prospective hepatitis C clinical trials. Latinos are the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the United States and it is predicted that by 2050, almost one out of every three Americans will be of Latino ethnicity.6

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been carried out in diverse populations. In Puerto Rico, a sero-epidemiologic survey estimated an overall prevalence of 2.3% for HCV among the adult population.7 However, a more recent sero-pre-valence survey conducted among adults aged 21-64 years in San Juan (the metro area of Puerto Rico and higher risk population), found 6.3% to be positive for HCV. This Latino population revealed a significantly greater prevalence of HCV infection compared to the general United States population aged 20-69 years (0.9-4.3%).8 In addition, the HCV-related mortality rate of Latino patients nearly doubles that of non-Latino white patients.9 Latino patients with CHC have shown a more aggressive inflammatory activity with fibrosis, and a greater risk of cirrhosis than in non-Latino white and African American patients.9–12 In other words, HCV infection poses a major public health problem in the Latino population.

Published reports suggest that the efficacy of CHC therapy is lower in Latinos than in non-Latino whites. Patients treated with peginterferon (Peg-IFN) alfa-2a plus ribavirin (RBV) in a multicenter, prospective study disclosed sustained virological response (SVR) rates to be 34% in the Latino white HCV genotype 1 patients as compared to 49% in the non-Latino white patients (p < 0.001).5 In this study, Latino ethnicity was demonstrated to predict a lower response in the logistic regression analysis. It is unknown whether the lower response to therapy in Latinos reported in this study could be related to an interferon ‘resistance’ or to differences in the allele frequencies of the IL28B gene, which have been proposed to explain the response rate differences in Caucasians, and African Americans.13 We know that IL28B polymorphisms are associated to IFN gene expression,14 and that the CC genotype has been associated with higher SVR rates in patients of European ancestry, African Americans and Latinos.15 However, the prevalence of the favorable CC genotype among Latinos is unknown. Yet, a small study of 102 Argentine patients with European ancestry did reveal only 18% of them to have the CC genotype.16

Nevertheless, almost all studies have reported the sustained virological response (SVR) for the Latinos to be lower than for the Caucasians yet higher than for the African Americans. Therefore, this suggests that the IL28B genotype prevalence is not the only factor to explain a diminished response to interfe-ron. Whether higher doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) and/or higher doses of RBV may improve the response to treatment in Latino patients is yet to be addressed.

Using early viral kinetics (VK) as an on-treat-ment predictor of response, have shown a good correlation with the therapeutic response to IFN-based therapy in several papers;17,18 however, information about the VK in Latino patients has not been published. Analyzing this information will determine if it also serves as a predictor of therapeutic response in Latino patients, and, thus, could contribute to the design of more effective therapies for Latino patients and other difficult-tocure populations.

The PROGRESS study was a large, randomized, international study, including Caucasian, Latino and African American patients, which investigated whether a 12-week fixed-dose induction regimen of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) and/or a highdose weight-based RBV dosage regimen could increase the SVR rates in patients with difficult-to-cure characteris-tics.19

For the purpose of this study, we used the available HCV RNA results from the patients enrolled in the PROGRESS study and stratified the data by race and ethnicity. The primary objectives of the VK analyses were to document the pattern of early VK in Latino patients and compare to Caucasian and African American patients, and to assess whether the 12 weeks VK was improved by higher doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) and/or RBV in Latino patients. A secondary objective was to assess the safety profile of those patients on the higher doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) and/or RBV during the initial 12 weeks and to monitor the evolution of any laboratory abnormalities after the postinduction period, when patients return to standard dose Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV.

Material and MethodsPatientsPatients enrolled in the PROGRESS study were HCV treatment-naive patients with difficult-to-cure characteristics, such as HCV genotype 1 infection, body weight ≥ 85 kg and a high baseline viral load (serum HCV RNA ≥ 400,000 IU/mL).

The details of the eligibility and exclusion criteria have been reported previously.15 The study population included 1145 patients. The race/ethnicity alternatives were Latinos (defined as Latino whites from the United States), Caucasians (non-Latino white), African American (non-Latino) or Other.

Study designThe PROGRESS study was a randomized, double-blind, international study. Its complete design, protocol, and primary results have been published elsewhere.15 All patients received 48 weeks of subcutaneous Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) (PEGASYS®, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) plus oral RBV (COPEGUS®, Roche, Basel, Switzerland); however they were randomized (in a 1:1:2:2 ratio; stratified by country) to one of four treatment regimens.

- •

Regimen A. Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/ week plus RBV 1,200 mg/day.

- •

Regimen B. Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) 180 μg/ week plus RBV 1,400 mg/day (body weight < 95 kg) or 1,600 mg/day (bodyweight ≥ 95 kg).

- •

Regimen C. Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) 360 μg/ week (intensive) for 12 weeks then 180 μg/week for 36 weeks plus RBV 1,200 mg/day.

- •

Regimen D. Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) 360 μg/ week (intensive) for 12 weeks then 180 μg/week for 36 weeks plus RBV 1,400 mg/day (body weight < 95 kg) or 1,600 mg/day (body weight ≥ 95 kg). The follow up period lasted 24 weeks after completing the treatment.

In the event of laboratory abnormalities or adverse events, the dose of either study drug could be reduced in a step-wise manner while remaining blind.

Treatment with Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) alone could be continued, but RBV monotherapy was not allowed. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each center, and each patient provided a written informed consent.

AssessmentsThe serum HCV RNA levels were determined by real-time PCR assay (COBAS® Ampliprep/COBAS® TaqMan® HCV test; detection limit 15 IU/mL, Roche Diagnostics North America, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). The viral load was measured at baseline, during treatment (on weeks 1, 2, 4, 12, 24 and 48) and during the follow-up period (on weeks 12 and 24).

The primary efficacy endpoint in the PROGRESS study was a SVR, defined as undetectable HCV RNA in the patient’s serum at the end of the untreated follow up period (study week 72). The secondary endpoints evaluated were the percentage of patients with undetectable HCV RNA levels at week 4, defined as a rapid virological response (RVR), at week 12, defined as a complete early virological response (cEVR), and at week 48, defined as an end of treatment response (EOT). Patients with missing serum HCV RNA results at one of these time points were considered to be non-responders for the corresponding endpoint. The relapse rate was determined by the percentage of patients with an EOT response who reverted to an HCV RNA-positive status during their follow-up evaluation.

Safety assessments were performed throughout the treatment and follow-up period; which included physical examinations, laboratory tests, documentation of clinical adverse events, and completion of the Beck Depression Inventory. Dose adjustments or withdrawals were performed for safety reasons or for intolerance.

Statistical analysisThe intention-to-treat population included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication according to the treatment group. Patients from all four individual treatment arms were stratified for the race/ethnicity criteria: Latino, Caucasian or African American. Since it is known that Peg-IFN has a much greater influence on the early VK profile than RBV, the data was pooled from the Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) standard dose regimens (A and B) and the Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) intensified dose regimens (C and D).

Within each race/ethnic group, the odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the purpose of the comparison of the virologic response rates between the patients receiving standard (A and B) vs. intensified (C and D) Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) dosing.

All patients who received at least one dose of the study medication and had at least one post-baseline safety assessment were included in the safety evaluation and analysis.

ResultsBaseline demographic and disease characteristicsFrom the total of 1145 patients comprised the ITT population, 51 (4%) were classified as Latino, 886 (77%) were classified as Caucasian, 124 (11%) were classified as African American and 84 (7%) were classified as Other.

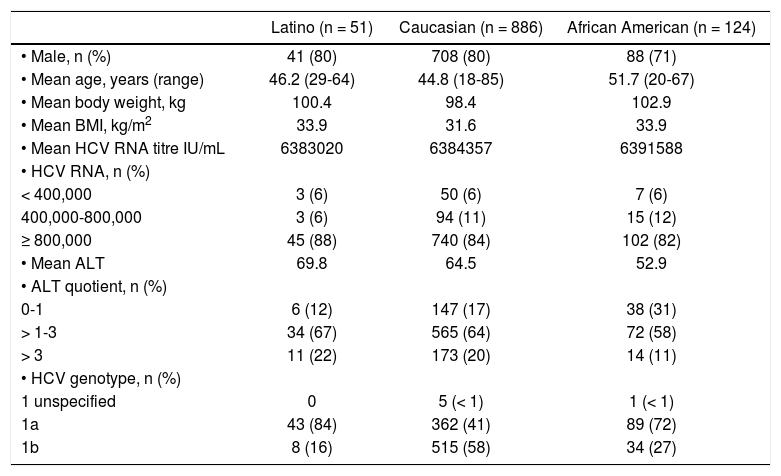

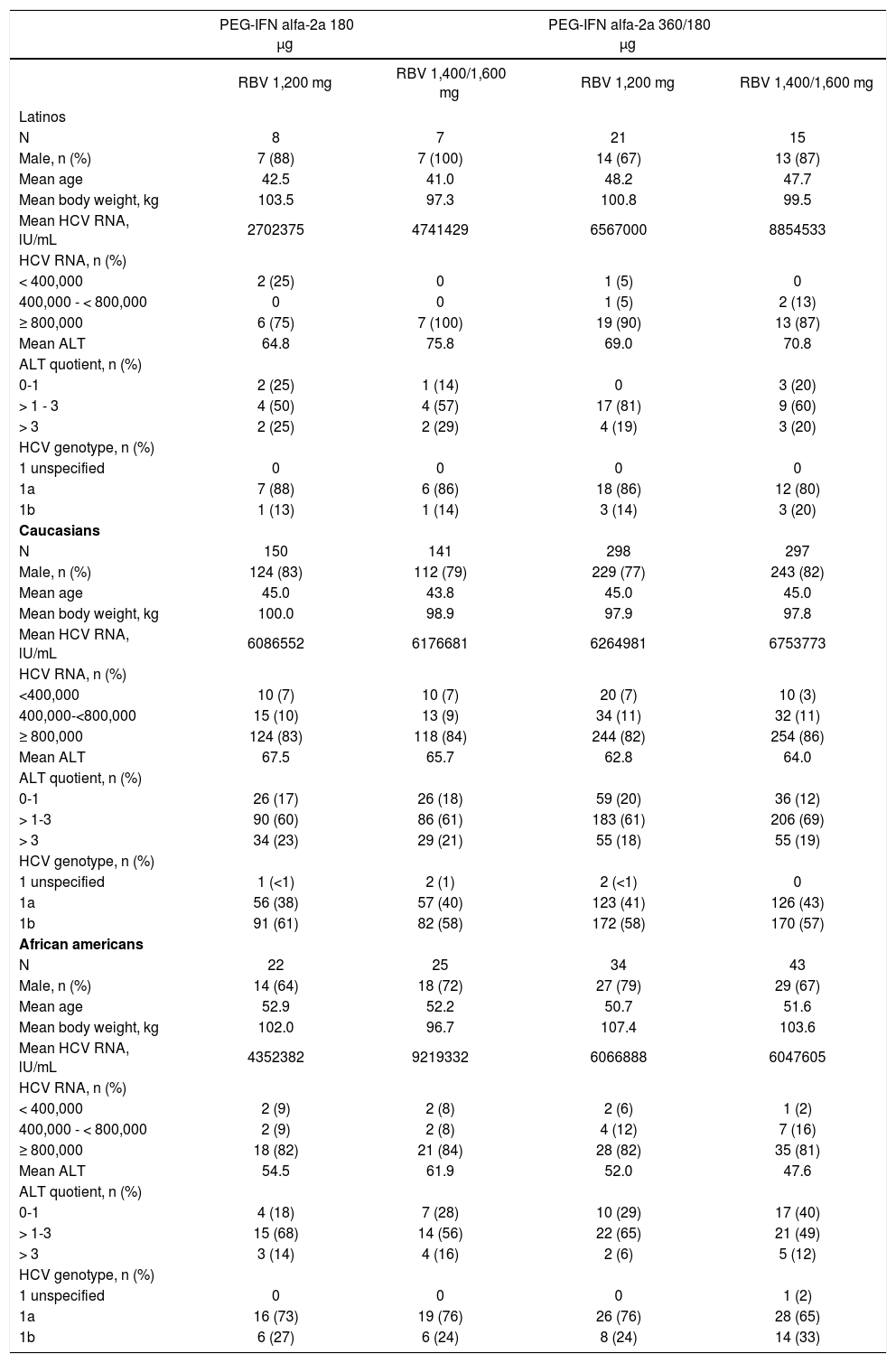

There were subtle differences in demographic data between Latino, Caucasian and African Americans (Table 1) and between the four individual treatment arms for each race or ethnicity (Table 2). The majority of the patients were male (71-80%), the mean age was 45 to 52 years, the mean body mass index was 32 to 34 kg/m2 and the great majority had a viral load ≥ 800,000 IL/mL (82-88% patients). Fewer African Americans were male, were somewhat older, and had slightly lower ALT levels (mean) as compared to Latinos and Caucasians (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics by race/ethnicity.

| Latino (n = 51) | Caucasian (n = 886) | African American (n = 124) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Male, n (%) | 41 (80) | 708 (80) | 88 (71) |

| • Mean age, years (range) | 46.2 (29-64) | 44.8 (18-85) | 51.7 (20-67) |

| • Mean body weight, kg | 100.4 | 98.4 | 102.9 |

| • Mean BMI, kg/m2 | 33.9 | 31.6 | 33.9 |

| • Mean HCV RNA titre IU/mL | 6383020 | 6384357 | 6391588 |

| • HCV RNA, n (%) | |||

| < 400,000 | 3 (6) | 50 (6) | 7 (6) |

| 400,000-800,000 | 3 (6) | 94 (11) | 15 (12) |

| ≥ 800,000 | 45 (88) | 740 (84) | 102 (82) |

| • Mean ALT | 69.8 | 64.5 | 52.9 |

| • ALT quotient, n (%) | |||

| 0-1 | 6 (12) | 147 (17) | 38 (31) |

| > 1-3 | 34 (67) | 565 (64) | 72 (58) |

| > 3 | 11 (22) | 173 (20) | 14 (11) |

| • HCV genotype, n (%) | |||

| 1 unspecified | 0 | 5 (< 1) | 1 (< 1) |

| 1a | 43 (84) | 362 (41) | 89 (72) |

| 1b | 8 (16) | 515 (58) | 34 (27) |

Eighty four patients were categorized as “Other” including American Indian (n = 7; 8%), Asian (n = 8; 10%), Black (n = 10; 12%), Native Hawaiian (n = 3; 4%), White (n = 45; 54%), other (n = 11; 13%).

Baseline characteristics in Latino, Caucasian and African American patients, by treatment group.

| PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg | PEG-IFN alfa-2a 360/180 μg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBV 1,200 mg | RBV 1,400/1,600 mg | RBV 1,200 mg | RBV 1,400/1,600 mg | |

| Latinos | ||||

| N | 8 | 7 | 21 | 15 |

| Male, n (%) | 7 (88) | 7 (100) | 14 (67) | 13 (87) |

| Mean age | 42.5 | 41.0 | 48.2 | 47.7 |

| Mean body weight, kg | 103.5 | 97.3 | 100.8 | 99.5 |

| Mean HCV RNA, lU/mL | 2702375 | 4741429 | 6567000 | 8854533 |

| HCV RNA, n (%) | ||||

| < 400,000 | 2 (25) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 |

| 400,000 - < 800,000 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (13) |

| ≥ 800,000 | 6 (75) | 7 (100) | 19 (90) | 13 (87) |

| Mean ALT | 64.8 | 75.8 | 69.0 | 70.8 |

| ALT quotient, n (%) | ||||

| 0-1 | 2 (25) | 1 (14) | 0 | 3 (20) |

| > 1 - 3 | 4 (50) | 4 (57) | 17 (81) | 9 (60) |

| > 3 | 2 (25) | 2 (29) | 4 (19) | 3 (20) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||||

| 1 unspecified | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1a | 7 (88) | 6 (86) | 18 (86) | 12 (80) |

| 1b | 1 (13) | 1 (14) | 3 (14) | 3 (20) |

| Caucasians | ||||

| N | 150 | 141 | 298 | 297 |

| Male, n (%) | 124 (83) | 112 (79) | 229 (77) | 243 (82) |

| Mean age | 45.0 | 43.8 | 45.0 | 45.0 |

| Mean body weight, kg | 100.0 | 98.9 | 97.9 | 97.8 |

| Mean HCV RNA, lU/mL | 6086552 | 6176681 | 6264981 | 6753773 |

| HCV RNA, n (%) | ||||

| <400,000 | 10 (7) | 10 (7) | 20 (7) | 10 (3) |

| 400,000-<800,000 | 15 (10) | 13 (9) | 34 (11) | 32 (11) |

| ≥ 800,000 | 124 (83) | 118 (84) | 244 (82) | 254 (86) |

| Mean ALT | 67.5 | 65.7 | 62.8 | 64.0 |

| ALT quotient, n (%) | ||||

| 0-1 | 26 (17) | 26 (18) | 59 (20) | 36 (12) |

| > 1-3 | 90 (60) | 86 (61) | 183 (61) | 206 (69) |

| > 3 | 34 (23) | 29 (21) | 55 (18) | 55 (19) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||||

| 1 unspecified | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| 1a | 56 (38) | 57 (40) | 123 (41) | 126 (43) |

| 1b | 91 (61) | 82 (58) | 172 (58) | 170 (57) |

| African americans | ||||

| N | 22 | 25 | 34 | 43 |

| Male, n (%) | 14 (64) | 18 (72) | 27 (79) | 29 (67) |

| Mean age | 52.9 | 52.2 | 50.7 | 51.6 |

| Mean body weight, kg | 102.0 | 96.7 | 107.4 | 103.6 |

| Mean HCV RNA, lU/mL | 4352382 | 9219332 | 6066888 | 6047605 |

| HCV RNA, n (%) | ||||

| < 400,000 | 2 (9) | 2 (8) | 2 (6) | 1 (2) |

| 400,000 - < 800,000 | 2 (9) | 2 (8) | 4 (12) | 7 (16) |

| ≥ 800,000 | 18 (82) | 21 (84) | 28 (82) | 35 (81) |

| Mean ALT | 54.5 | 61.9 | 52.0 | 47.6 |

| ALT quotient, n (%) | ||||

| 0-1 | 4 (18) | 7 (28) | 10 (29) | 17 (40) |

| > 1-3 | 15 (68) | 14 (56) | 22 (65) | 21 (49) |

| > 3 | 3 (14) | 4 (16) | 2 (6) | 5 (12) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||||

| 1 unspecified | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| 1a | 16 (73) | 19 (76) | 26 (76) | 28 (65) |

| 1b | 6 (27) | 6 (24) | 8 (24) | 14 (33) |

- •

Viral kinetics.Figure 1 A-C demonstrates the mean HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL) change over the first 12 weeks directly comparing each treatment regimen, segregated by Latino, Caucasian and African American patients. In Latinos, the greatest decline in viral load was consistently achieved with Regimen D (i.e. higher dose Peg-IFN and RBV) as compared to Regimens AtoC (Figure 1A). In Caucasians, the rate of viral load reduction tended to be consistently slightly higher with the intensified dose regimens (C and D) as compared to the standard dose regimens (A and B); however, there were no apparent differences between regimens A and B or between regimens C and D (Figure 1B). In African Americans, the decline in viral load was similar, irrespective of the treatment regimen (Figure 1C). Figure 2 demonstrates the same data (mean change in HCV RNA over the first 12 weeks) but directly comparing the race/ethnicity within each treatment group, which display similar response curves by the Latinos and Caucasians within the treatment groups A and D.

Figure 3A-C demonstrates the mean HCV RNA change over the first 12 weeks for the pooled data: A and B (standard Peg-IFN alfa-2a dose) vs. C and D (intensified Peg-IFN alfa-2a dose). In both Latino and Caucasian patients, the decline in viral load was consistently greater in the intensified dose as compared to the standard dose group throughout the 12 week treatment period (Figure 3A–3B). However, the decline in the viral load in African American patients remained similar irrespective of doses (Figure 3C). Figure 4 demonstrates the same data (mean change in HCV RNA over the first 12 weeks) but directly comparing the race/ethnicity within each pooled treatment group, which display three distinctive response curves where the Latinos are in-between the African Americans and the Caucasians; however by the end of the 12 weeks the response in the Latinos closely approximates that of the Caucasians.

- •

Viral clearance.Figure 5A-C demonstrates the virological response over the first 12 weeks for the pooled data. In Latino patients, the virological response at week 4 (RVR) was similar between the two pooled treatment regimens (standard dose: 6.7%; intensified dose: 5.6%), but by week 12 the cEVR was greater in the patients treated with the intensified dose (58.3%) as compared to the standard dose (46.7%) (Figure 5A). The virologic response in the Caucasian patients was consistently greater throughout the 12 weeks of treatment in the intensified dose group as compared to the standard dose group (RVR: 19.2 vs. 12.7%, respectively; cEVR: 63.0 vs. 58.1%) (Figure 5B). In the African American patients, the RVR rates at week 4 were higher in the standard dose group (8.5 vs. 3.9%) but at week 12 the relationship inversed, having the cEVR rates higher in the intensified dose group (32.5 vs. 27.7%) (Figure 5C). Figure 6 demonstrates the virological response over the first 12 weeks but directly comparing the race/ ethnicity within each treatment group, which again display three distinctive response curves where the Latinos are in-between the African Americans and the Caucasians.

In this difficult to treat population, the Latino patients achieved higher SVR rates in the intensified dose group (36.1%)(13/36) as compared to the standard dose group (26.7%)(4/15). In Caucasian and African American patients, the SVR rates were similar between the two treatment groups: Caucasians 42.3% (123/291) vs. 43.9% (261/595) and African Americans 21.3% (10/47) vs. 19.5% (15/77) (data not shown).

- •

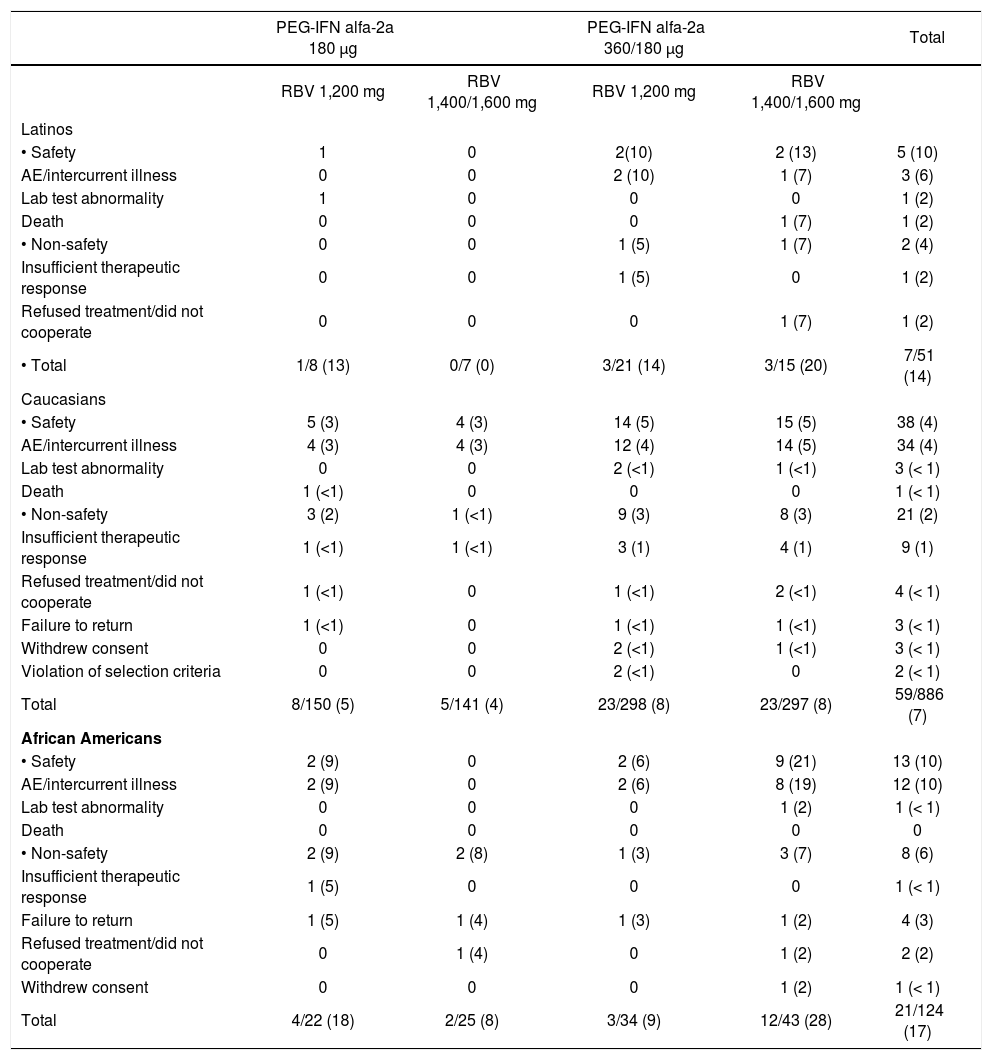

Withdrawal from treatment. During the first 12 weeks of therapy, 7 of 51 (14%) Latino patients, 59 of 886 (7%) Caucasian patients and 21 of 124 (17%) African American patients withdrew from the Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) treatment, disclosing no noticeable differences across the treatment groups (Table 3). The withdrawals from Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) treatment due to, specifically, safety reasons were reported in 5 of 51 (10%) Latinos, 38 of 886 (4%) Caucasian, and 13 of 124 (10%) African Americans, having a similar proportion across the four treatment groups (Table 3). The proportion of patients that withdrew from RBV therapy, due to safety reasons, during the first 12 weeks was similar among Latinos, Caucasians and African Americans; 10, 4 and 10% respectively (data not shown).

Table 3.Patients withdrawn from Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) during the first 12 weeks.

PEG-IFN alfa-2a 180 μg PEG-IFN alfa-2a 360/180 μg Total RBV 1,200 mg RBV 1,400/1,600 mg RBV 1,200 mg RBV 1,400/1,600 mg Latinos • Safety 1 0 2(10) 2 (13) 5 (10) AE/intercurrent illness 0 0 2 (10) 1 (7) 3 (6) Lab test abnormality 1 0 0 0 1 (2) Death 0 0 0 1 (7) 1 (2) • Non-safety 0 0 1 (5) 1 (7) 2 (4) Insufficient therapeutic response 0 0 1 (5) 0 1 (2) Refused treatment/did not cooperate 0 0 0 1 (7) 1 (2) • Total 1/8 (13) 0/7 (0) 3/21 (14) 3/15 (20) 7/51 (14) Caucasians • Safety 5 (3) 4 (3) 14 (5) 15 (5) 38 (4) AE/intercurrent illness 4 (3) 4 (3) 12 (4) 14 (5) 34 (4) Lab test abnormality 0 0 2 (<1) 1 (<1) 3 (< 1) Death 1 (<1) 0 0 0 1 (< 1) • Non-safety 3 (2) 1 (<1) 9 (3) 8 (3) 21 (2) Insufficient therapeutic response 1 (<1) 1 (<1) 3 (1) 4 (1) 9 (1) Refused treatment/did not cooperate 1 (<1) 0 1 (<1) 2 (<1) 4 (< 1) Failure to return 1 (<1) 0 1 (<1) 1 (<1) 3 (< 1) Withdrew consent 0 0 2 (<1) 1 (<1) 3 (< 1) Violation of selection criteria 0 0 2 (<1) 0 2 (< 1) Total 8/150 (5) 5/141 (4) 23/298 (8) 23/297 (8) 59/886 (7) African Americans • Safety 2 (9) 0 2 (6) 9 (21) 13 (10) AE/intercurrent illness 2 (9) 0 2 (6) 8 (19) 12 (10) Lab test abnormality 0 0 0 1 (2) 1 (< 1) Death 0 0 0 0 0 • Non-safety 2 (9) 2 (8) 1 (3) 3 (7) 8 (6) Insufficient therapeutic response 1 (5) 0 0 0 1 (< 1) Failure to return 1 (5) 1 (4) 1 (3) 1 (2) 4 (3) Refused treatment/did not cooperate 0 1 (4) 0 1 (2) 2 (2) Withdrew consent 0 0 0 1 (2) 1 (< 1) Total 4/22 (18) 2/25 (8) 3/34 (9) 12/43 (28) 21/124 (17) - •

Adverse events. The incidence of individual adverse events during the first 12 weeks of treatment resulted comparable across the three race/ ethnic groups and four treatment regimens; specifically, 96% reported in Latinos, 97% in Caucasians, and 94% in African Americans. The most common events were headache, fatigue, nausea, pyrexia and chills. The development of pneumonia was reported in 7 Caucasian patients (<1%); 1 in group A, 1 in group B, 2 in group C, and 3 in group D; however, no reports of pneumonia were reported in the Latino or African American patients.

The mean body weight loss after 12 weeks of treatment resulted 3.3kg in Latinos, 4.1 kg in Caucasians and 4.6 kg in African Americans (Figure 7). As expected, the weight loss tended to be greater among patients receiving the intensified dose of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV as compared to the standard dose. The body weight continued to decline in all treatment groups with continued Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD)/RBV therapy; in fact, at the end of the treatment regimen (at week 48) the mean body weight loss was 6.3 kg in Latinos, 7.5 kg in Caucasians and 7.9 kg in African Americans. After a 24 weeks follow up period (at week 72), the body weight had increased, resulting in a final mean body weight loss of 4.1, 2.9 and 4.3 kg, respectively.

A decline in the hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, and platelet count was observed in all three ethnic/racial groups and in all treatment regimens during the first 12 weeks of treatment, and subsequently till the end of therapy, at 48 weeks (Figure 8). The hemoglobin level and the white blood cell count displayed a relatively constant decline during the full 48 weeks treatment period. The patients receiving the 12 weeks intensified doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40 KD) plus RBV experienced a more drastic decline in the platelet count as compared to those who received the standard dose. During the following 36 weeks of therapy, where all patients received the standard dose of Peg-IFN alfa-2a plus RBV, the platelet counts stabilized in the pooled intensified dose group.

During the first 12 weeks of treatment period, two deaths were reported. One was a Latino patient from group D, whom died on day 72 due to hepatic failure, and the other was a Caucasian patient from group A, whom died on day 39 due to a myocardial infarction. Neither of the deaths was considered to be treatmentrelated.

No deaths were reported in the African Americans.

- •

Peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD). During the first 12 weeks of treatment, the dose of Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) required modification, due to an adverse event or laboratory abnormality, in only 9 Latino patients (18%); where all of these 9 patients had been randomized to an intensified dose groups (C or D). On the other hand, the Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) dose required modification in 168 (19%) Caucasian patients (12% standard, 23% in-tensified) and in 23 (19%) African American patients (23% standard, 16% intensified). The most common reason for the modification of the Peg-IFN alfa-2a dose in all three racial/ethnic groups was the advent of neutropenia.

- •

Ribavirin. During the first 12 weeks, the dose of RBV required modification, due to an adverse event or laboratory abnormality, in 18% of the Latinos, 17% of the Caucasians and 22% of the African Americans. The most common reason for modification of the dose was the advent of anemia.

This retrospective analysis provides further evidence for racial and ethnic differences in the response to Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV therapy in patients with CHC. The results indicate that after 12 weeks of treatment with Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) plus RBV, Latino patients infected with the HCV genotype 1 tend to achieve greater virological response with an intensified dose as compared to the standard dose of Peg-IFN alfa-2a. Although the Latino patients initially achieved similar RVR rates at week 4 with both dose groups, and were much lower as compared to the Caucasian patients; by week 12, much greater cEVR rates were observed in the intensified dose group, and were, in fact, comparable to the cEVR rates among the Caucasian patients. Higher SVR rates were also reported in the intensified dose group in the Latino patients (data not shown). These findings suggest that Latinos have a slower clearance of the HCV which ultimately results in a lower SVR than Caucasians; correlating with the fact that RVR is a better predictive value for SVR than cEVR.20,21 Therefore, the differences of SVR among Latinos and Caucasians may be partially explained by these described differences in the early viral kinetics but this aspect alone does not explain the differences among the ethnic and racial groups. The achievement of higher SVR rates with the intensified doses in the Latino group suggests that this strategy may be capable of accelerating the early viral kinetics; however, it is not enough to overcome the overall non responsiveness to interfe-ron. Recent publications have demonstrated the benefit of higher doses of Peg-IFN to obtain a higher SVR in difficult to treat populations.22

For Caucasian patients, both RVR and cEVR rates were greater with the intensified dose group; however, SVR was similar between the treatment groups. The virologic response rates for African Americans appear to be unaffected by the Peg-IFN alfa-2a dose (40KD) and by week 12, are lower as compared to both Latino and Caucasian patients. These results again demonstrate a certain ‘resistance’ to interferon in the African American population, which correlates with the dismal SVR when treated with Peg-IFN and RBV.

The 12 week safety profile of Peg-IFN (40KD) plus RBV in the Latino patients is similar to that of the Caucasian and African American patients, irrespective of the treatment dose, and resulted, in fact, consistent with the known safety profile of Peg-IFN alfa-2a plus RBV. A greater, but reversible, decrease in body weight and the platelet count was observed in the intensified dose group relative to the standard dose group in all three ethnic or racial populations. The Peg-IFN alfa-2a (40KD) dose had a minimal impact on the hemoglobin level or the white blood cell count. Therefore, differences in the safety parameters (i.e. dose modifications o discontinuation of drugs) cannot explain the obtained VK results among the ethnic or racial groups.

Differences in the allele frequencies of the IL28B gene have, for the most part, explained the differences in the virological response rates seen in Caucasians, African Americans and Asians.13 A great limitation of this analysis is that the PROGRESS study was initiated before the IL28B SNP was identified as a genetic predictor of response, and therefore was not assessed in this study. Whether the IL28B genetic patterns may influence the response to intensified doses of Peg-IFN alfa-2a/RBV therapy in Latino patients remains yet to be determined.

This study has limitations, mainly due to the small number of patients in the Latino and African American groups as compared to the Caucasian population. Because of the barriers for minority groups to obtain CHC treatment and their poor representation in clinical trials, it has been a challenge to analyze information pertinent to Latinos. In spite of the small sample size, the findings obtained in this study are of importance to physicians treating Latino patients. To our knowledge this is the only study that reports viral kinetics in Latinos when treated with Peg-IFN alfa-2a and RBV. Furthermore, this is the first analysis of the VK in Latinos while comparing treatment with standard versus intensified Peg-IFN doses.

Although we are now in the rapidly evolving era of directly acting antiviral drugs, this data remains pertinent since we still anticipate the continued need for interferon in the treatment of many patients. These results also add to a growing body of evidence that indicate existing differences in the treatment responses among ethnic groups; therefore further studies among Latino patients are needed.

Abbreviations- •

CHC: chronic hepatitis C.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

Peg-IFN: peginterferon.

- •

RBV: ribavirin.

- •

SVR: sustained virological response.

- •

VK: viral kinetics.

- •

RVR: rapid virological reponse.

- •

cEVR: complete early virological response.

- •

EOT: end of treatment response.

Funding for the PROGRESS study, and support for third-party statistical and writing assistance was provided by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Grants and Financial Support: N/A