Chronic hepatitis B has a variable course in disease activity with a risk of clinical complications like liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. As clinical symptoms present in a late stage of the disease, identification of risk factors is important for early detection and therefore improvement of prognosis. Recently, two REVEAL-HBV studies from Taiwan have shown a positive correlation between viral load at any point in time and the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Due to differences in viral and host factors between Asians and other populations, it is unclear whether these results can be extrapolated to different populations. This manuscript will discuss viral predictors of hepatitis B related liver disease in relation to ethnic origin.

In 1965, Blumberg, et al. discovered the Australia antigen, currently known as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), when blood from an Aboriginal Aus-trialian was combined with serum of a patient with haemophilia.1 HBsAg is currently used as a diagnostic test to detect past and present hepatitis B infection. Currently, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection still have a global impact, with an estimated 2 billion people worldwide.2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), of those subjects, 350 million are chronically infected with the virus.2 In Europe, the prevalence of HBsAg positive carriers varies from below 0.5 to 3.8% between countries, with increasing rates from North-West Europe to South-East Europe.3 Between 500,000-700,000 patients worldwide die annually as a result of HBV-re-lated liver disease like decompensated cirrhosis, end stage liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2,4

HBV can induce inflammation of the liver, mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes against infected he-patocytes.5,6 Chronic liver inflammation may cause fibrosis and eventually increase the risk of HBV-re-lated disease, i.e. cirrhosis and HCC. As these complications could develop in an asymptomatic patient, it is essential to identify risk factors for early detection and treatment. In the South-East Asian area, which is labeled as a high endemic region for hepatitis B, several studies in adults patients have de-monstrated a positive correlation between the viral load at any point in time and the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.7–11 However, it is unknown whether this correlation also applies to other populations due to differences in viral and host factors.

Therefore, this manuscript will first summarize the available evidence on the viral load as predictor of HBV-related liver diseases. Thereafter, differences between Asians and other populations will be discussed indicating that generalization of these results must be done with caution.

Chronic Hepatitis BBefore addressing the correlation between viral load and HBV-related liver disease, the course of HBV and predictors of HBV-related disease will briefly be discussed.

Chronic HBV is characterized by an irregular course in disease activity with variations in periods of liver injury (e.g. the immune tolerant phase without liver injury and the immune clearance phase which is associated with liver injury). These changes in the liver can occur without clinical symptoms. Liver injury can either be detected by biochemical changes expressed as elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels or via histological changes at liver biopsy showing necrosis and infla-mmation.12,13 It is generally accepted that prolonged inflammation and recurrent liver damage may eventually lead to hepatic fibrosis.14,15 Ultimately, when fibrosis persists, progressive loss of liver parenchyma and substitution with fibrous tissue will lead to cirrhosis.16 Once cirrhosis is present, there is a 5-year cumulative risk of developing HCC between 10% in West Europe and 17% in East Asia.17

Until recently, the following risk factors have been associated with development of HBV-related liver disease: age, male gender, alcohol consumption, smoking, carrier state of hepatitis B virus e-antigen (HBeAg), the presence of core or precore mutations, hepatitis B genotype C, coinfection with hepatitis C, hepatitis D or HIV, exposure to aflatoxin and diabetes mellitus.18–27 With growing understanding in the pathogenesis of HBV-related liver disease, viral factors like the viral load and genotype are also recognised as important determinants of liver disease progression.

HBV Viral Load and HBV-Related Liver DiseaseHBV is a non-cytopathic, hepatotropic DNA virus, which is quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), representing the rate of viral replication. It has been established that HBV viral load can remain stable over time until HBeAg sero-conversion or a hepatitis flare occurs.28,29 Therefore, it has been hypothesized that a high HBV viral load could be associated with the development of HBV-related liver disease. For instance, Chen, et al. showed that compared to patients with an unde-tectable HBV DNA, the relative risk (RR) for HCC related mortality was 11.2 (95% confidence interval 3.6-35.0) in patients with high HBV DNA (defined as ≥ 10E5 copies/mL).10 Others, showed similar re-sults.11,30–36

Recently, two landmark studies of the REVEAL-HBV study group have established a correlation between the HBV viral load and advanced liver disease, i.e. cirrhosis and HCC.7,8 These two large prospective observational cohort studies in 7 Taiwanese townships with chronic hepatitis B, have demonstrated a strong correlation between a single serum HBV viral load on the one hand and the occurrence of cirrhosis and HCC on the other hand. In the first study, Iloeje, et al. examined, in a total of 3,582 untreated patients, the role of serum HBV viral load as a predictor for progression to cirrhosis.7 During a mean follow-up time of 11 years, the incidence of cirrhosis was positively correlated with HBV viral load at study entry, independent of HBeAg status and serum ALT level. This ranged from 4.5% in patients with a viral load below 300 copies/mL to 36.2% in patients with a viral load above 10E6 copies/mL.

The second study evaluated the relationship between serum HBV viral load and the risk of HCC.8 After adjustment for other risk factors like age, HBeAg status and cirrhosis, HBV viral load remained an independent risk factor for HCC, with a correlation between increasing HBV viral load and incidence of HCC. The cumulative incidence, in a follow-up period up to 13 years, of developing a HCC ranged from 1.3% in patient with a viral load below 300 copies/mL to 14.9% in patients with a viral load of 10E6 copies/mL or greater.

From these studies, showing that HBV viral load can predict the development of HBV-related liver diseases at any point in time between ages 30 and 65, it follows that without treatment, high HBV viral load could negatively affect the prognosis in the course of this disease. Indeed, additional studies confirmed that higher viral loads are associated with higher mortality rates in chronic HBV-infected patients.10,37,38

Thus, these results indicate that a high HBV viral load is associated with an unfavorable outcome, in terms of HBV-related liver disease.

Differences Between Asians and Other PopulationsAlthough a correlation in Asians has been established, it is unclear whether this also applies to other populations. In other diseases, the natural course of a disease or effect of therapy has been shown to be different between Asians and other populations. For example, a recent publication demonstrated that the risk of death from any cause among Asians, as compared to Europeans, seemed to be more strongly affected by a low BMI than by a high BMI.39 Also, in the treatment of HIV, Asians differ from Caucasians in their prevalence of lipodys-trophy, hyperlipidaemia, and insulin resistance during HAART therapy.40

With respect to HBV, there are no studies examining the impact of differences in habits, local conditions and lifestyle on the course of hepatitis B between Asians and other populations. Therefore, at present it remains unclear whether these factors contribute to differences in the pathogenesis, prognosis and treatment outcome. However, differences in age of acquiring HBV infection, HBV genotype and HBeAg seroconversion have been described between Asians and other populations. The potential impact of these differences is discussed below.

Age of acquiring HBV infectionThe age of HBV infection, whether acquired in childhood or at adult age, could play a role in the natural history of HBV. In the Asian-Pacific region, HBV is obtained early in life by either vertical (perinatal) transmission during birth or by horizontal transmission in early childhood.41–44 In a study in Taiwan, designed to investigate preventive strategies in e-antigen positive HBsAg carrier mothers, perinatal transmission reached up to 88%.45 Of note, Burk, et al. showed that, in Asians, maternal viral load also seemed to determine the outcome of perinatal hepatitis B virus in unvaccinated infants.46 In their study in Taiwanese women, the hazard ratio for having a persistently infected infant increased up to 147.0 (95% confidence interval 6.6-6,894) with increasing HBV viral load. So, vertical transmission is an important route by which Asians acquire HBV at an early age.

Another source of transmission in Asians is horizontal transmission through intrafamilial spread contact by household carriers. Numerous studies have shown that children of HBsAg positive patients have an increased risk of infection with HBV through exchange of items which contain infected body secretions, e.g. chewing gum or tooth brus-hes.41,47–51 A prospective study in India, which examined household contacts from known HBsAg positive patients, revealed that prevalence of HBsAg in children until 15 years of age was 37%.41 Supplementary studies have shown that up to 49.2% of HBV infections in children until the age of four years take place through this transmission route, e.g. through transmissions within nurseries and kindergartens.2,43,44 Thus, besides perinatal transmission, horizontal spread is responsible for a substantial proportion of HBV infections in early childhood.

On the other hand, in low endemic areas like in Northwest Europe, HBV infection is mostly acquired at a later age compared to Asians. In a national, case-based study in Norway, the incidence of chronic HBV was highest in people aged 20-29.52 Furthermore, this age group was also at highest risk of acquiring acute HBV. Of particular note, the group of chronic HBV-infected patients contained more immigrants from high endemic regions than native Norwegians. Additional studies showed that, for acute HBV, horizontal transmission (mostly blood-blood or sexual contact), is the main route of infection in these low endemic countries.53,54 In the previously mentioned Norwegian study, 64% of all cases of acute HBV infections were acquired through intravenous drug use.52 A study in the Netherlands, another low endemic country, assessed the possible transmission routes of 464 patients with chronic hepatitis B.54 This study showed that both perinatal and horizontal transmission were responsible for infection, but in patients born in the Netherlands, (homo-)sexual transmission appeared responsible for a larger proportion of infections compared to patients originally born elsewhere.

Thus, differences in the age of acquiring HBV infection (childhood in Asians vs. native adults in low endemic, non-Asian populations) might play a role in the natural history of HBV infections.

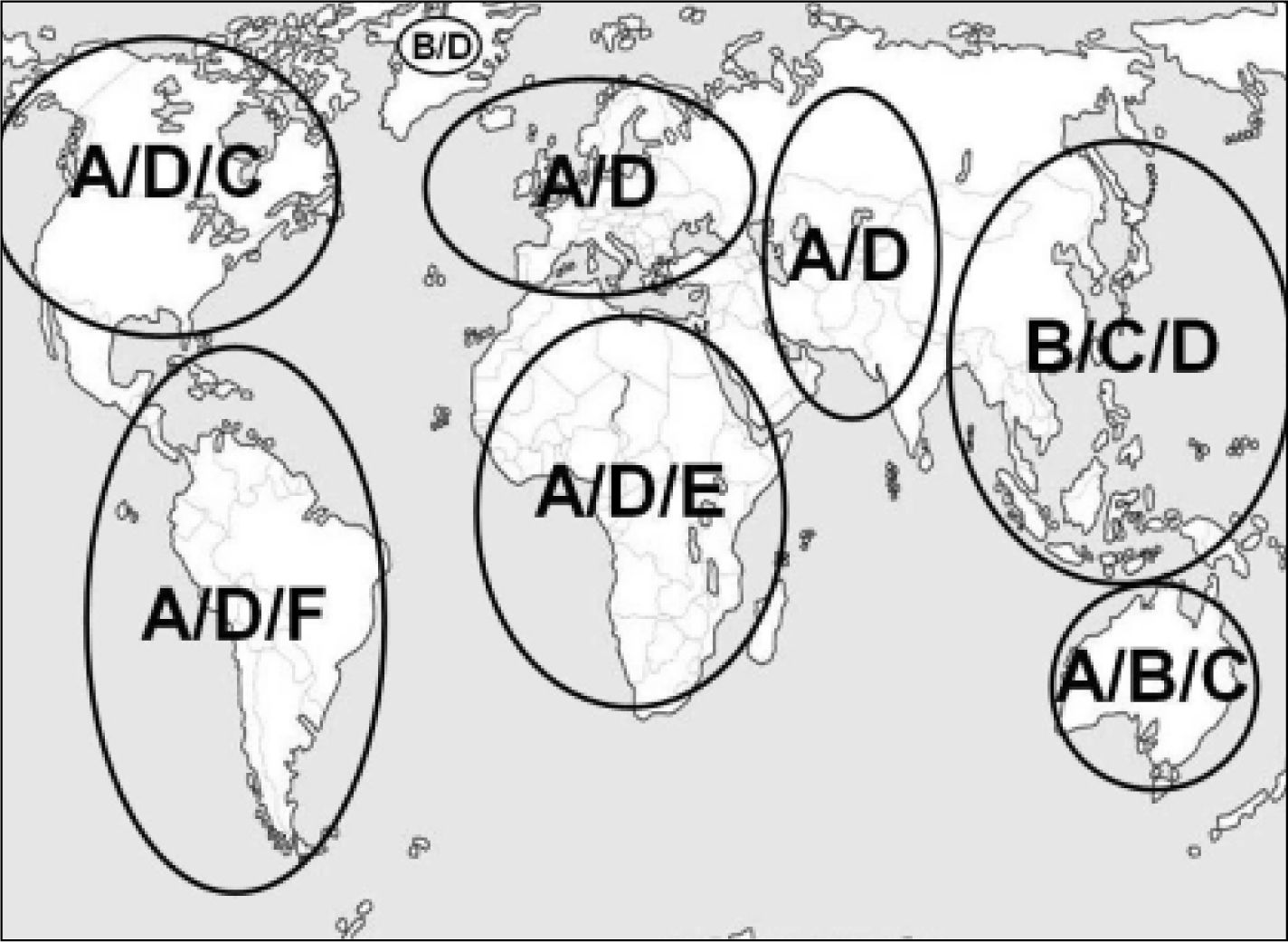

GenotypeCurrently, there are 10 different genotypes of HBV with a discongruity of 8% in the genomic HBV sequence.55–63 Although HBV genotype currently is only relevant for interferon-alfa therapy with regard to clinical decision making, there is an increased understanding of its role in the course of HBV infection. Since most studies related to genotype have been conducted in areas where genotypes A, B, C and D predominate, these are most extensively investigated. Figure 1 illustrates the global distribution of the dominant genotypes.

Several studies in Asians have shown that patients with genotype C infection have an unfavorable outcome compared to genotype B.9,11,64–69 Similar to others, Yang, et al. conducted a large prospective cohort study on the association between genotype and the occurrence of HCC.64–68 In 2,762 HBsAg positive Taiwanese patients, they demonstrated that the risk of HCC development was highest among participants infected with genotype C compared to genotype B. In another study, Liang, et al. showed that patients with genotype C had a worse disease-free survival rate compared to genotype B.69 In line with these findings, several studies have shown that genotype B is associated with a higher rate of HBe-Ag negativity compared to genotype C. Two factors could explain this observation. First of all, patients with genotype B tend to experience spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion at a younger age compared to patients with genotype C.70,71 In a retrospective Chinese study, mean age at HBeAg seroconversion was 27 ± 2 years in patients with genotype B compared to 35 ± 2 years in patients with genotype C (p < 0.05).70 Second, genotype B is associated with a higher prevalence of precore (G1896A) and core promoter (A1762T, G1764A) mutations, resulting in loss of HBeAg, compared to genotype C.70,72

Studies comparing genotype A and D resulted in contradictory data regarding the development of HBV-related liver disease.73–76 Kumar, et al. showed that genotype A was more often associated with ALT elevation, HBeAg positivity, absence of anti-HBe and cirrhosis after age 25 compared to genotype D.73 Contrary to this, Thakur, et al. demonstrated that HBV genotype D, compared to genotype A, was associated with more severe liver disease and might predict the occurrence of HCC in young patients.75

Response to treatment also seems to be influenced by genotype. Patients infected with genotype A and B respond better to treatment with pegylated inter-feron-alfa compared to genotype C and D.77–79 Thus, differences in genotypes can alter the disease severity, course of HBV infection and treatment outcome.

Hepatitis B e-antigen seroconversionThe prevalence of HBeAg positivity varies between different populations. Two Greek studies in HBsAg positive women between age 20 and 30 showed a low prevalence of HBeAg positivity.80,81 In these studies, the route of transmission in these patients was not described. One of the studies reported a prevalence of HBeAg positivity of 7.3%, dropping to 5.7% (6 of 105 instead of 8 of 109) when patients with an Asian origin were subtracted in this stu-dy.80 On the other hand, in Chinese HBV positive women of the same age, a large cohort study revealed a HBeAg positivity of 43%.82 Of note, in this cohort, approximately 10% of all patients over 40 years remained HBeAg positive. This might suggest that Asians have a higher prevalence and longer duration of HBeAg positivity compared to the Euro-pean population.

Differences in HBeAg seroconversion rate might influence the progression to HBV-related liver disea-se.80–84 A few cohort studies have investigated the re-lationship between a delayed HBeAg seroconversion and progression to HBV-related disease in the natural course of HBV.34,83–85 After HBeAg seroconver-sion an annual incidence of cirrhosis varies between 0.5% and 0.9% in therapy-naïve patients,83,85 while in HBeAg positive patients 5% progressed to cirrhosis in a mean follow-up of 10.5 ± 4.3 years, with age at HBeAg seroconversion being an independent risk factor for developing cirrhosis (hazard ratio of 3.4 with 95% confidence interval 1.4-8.2).83 These results are in line with the results from the REVEAL-HBV studies.7,8 A possible explanation for this association could be that HBeAg positivity, which indicates sustained HBV replication, may induce an accelerated rate of cell turnover leading to a higher degree of hepatic fibrosis and malignant transformation as a result of continuous or recurrent hepato-cyte necrosis and regeneration.34,83

Taken together, although several studies postulate a difference in the Asian-Pacific region compared to other areas in delayed HBeAg seroconversion and its association with the development of HBV-related liver diseases, the exact impact of this association will have to be determined in future studies.

Cobra StudySince a part of the HBV-infected population lives in Western Europe and North America, it is important to investigate whether the correlation between HBV viral load and the occurrence of HBV-related liver diseases, found in Asians, are also applicable to other populations.

The Public Health Service Amsterdam was responsible for vaccinating newborns from mothers with chronic hepatitis B from 1989 through 2009, leading to an unique cohort of HBV positive women who could be eligible for this purpose.86 Of these women, blood samples have been collected and stored at the time of HBV diagnosis. This will be the basis for a study, the ‘Cohort of hepatitis B research of Amsterdam (COBRA)’ study. This study is designed to investigate the correlation between a single hepatitis B viral load and HBV-related liver disease in a non-Asian population. Also, since there is evidence emerging in the clinical use of quantitative HBsAg, this study will further investigate the relationship between quantitative HBsAg, HBV viral load and HBV-related liver disease.

ConclusionIn conclusion, two landmark studies have provided evidence that a single elevated serum HBV viral load predicts disease progression in HBV. In this manuscript, we have demonstrated that geographical differences in viral and host factors could in part influence the pathogenesis of hepatitis B. Therefore, further prospective clinical studies in non-Asians will have to determine the role of these findings in other populations.

Abbreviations- •

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase.

- •

anti-HBe: Hepatitis B e antibody.

- •

BMI: Body mass index.

- •

copies/mL: Copies per milliliter

- •

DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid.

- •

HAART: Highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

- •

HBeAg: Hepatitis B e-antigen.

- •

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen.

- •

HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

- •

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

- •

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

- •

WHO: World Health Organization.

S. Harkisoen: literature search and selection, writing manuscript. J.E. Arends: literature search, writing manuscript. Karel J. van Erpecum: writing manuscript. A. van den Hoek: writing manuscript. A.I.M. Hoepelman: writing manuscript and supervising.

Conflict of InterestSoeradj Harkisoen: no conflict of interest. Joop E. Arends: participates in advisory board of MSD. Karel J. van Erpecum: was member of advisory boards of BMS and Gilead and received research support by Schering Plough. Anneke van den Hoek: no conflict of interest. Andy I.M. Hoepelman: received grants from Roche, Gilead, Merck and ViiV Healthcare and is an advisor for Gilead, Merck, ViiV Healthcare and Janssen.