Liver transplant candidates and recipients are at high risk of psychological distress. Social, psychological and psychiatric patterns seem to influence morbidity and mortality of patients before and after transplant. An accurate organ allocation is mandatory to guarantee an optimal graft and recipient survival. In this context, the pre-transplant social, psychological and psychiatric selection of potential candidates is essential for excluding major psychiatric illness and for estimating the patient compliance. Depression is one of the most studied psychological conditions in the field of organ transplantation. Notably, an ineffectively treated depression in the pre-transplant period has been associated to a worst long-term recipient survival. After transplant, personalized psychological intervention might favor recovery process, improvement of quality of life and immunosuppressant adherence. Active coping strategy represents one of the most encouraging ways to positively influence the clinical course of transplanted patients. In conclusion, multidisciplinary team should act in three directions: prevention of mood distress, early diagnosis and effective treatment. Active coping, social support and multidisciplinary approach might improve the clinical outcome of transplanted patients.

Today, organ transplantation represents a great therapeutic option for many diseases but transplant recipients can develop many psychological distresses such as re-experiencing (of a past experience or elements of a past experience), avoidance (defined as the effort to avoid dealing with a stressor), excitement (stated as emotional state of enthusiasm, eagerness and anticipation) and sense of responsibility toward donor, clinicians and family members [1–5].

Liver transplantation (LT) comprises a complex and articulated clinical process [4]. Candidates waiting for LT typically present life-threatening disease needing donor organ for surviving and risk of death on waitlist is difficult to predict (i.e. 4–5% in Italy) [6,7]. When the organ from a donor becomes available, patients have to undergo major surgery, followed by short or long intensive care unit hospitalization. After LT, recipients should adapt to immunosuppressive drugs and restrictive life-style rules. Furthermore, potentially life-threatening complications such as rejection of the graft, cardiovascular diseases and de novo extra-hepatic cancer might occur. As expected, the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients in both pre and post-LT period can be impaired [8]. For the same considerations, candidates to LT and recipients are at high risk of somatization and mood disorders. All these phenomena generally tend to be attenuated during the first year after LT worsening later again. Interestingly, both HRQoL and psychopathology can be reinforced by the continuous medicalization embodied by the life-long immunosuppressant therapy [9].

Notably, prognosis of organ transplantation can be influenced by many social, psychological and psychiatric factors. In different (heart transplant) or very different (bone marrow transplant) contexts, pre-transplant psychiatric and psychosocial variables such as treatment adherence, social support, and coping (defined as the attitude to invest own conscious effort to answer to some difficulty, in order to try to control, minimize or tolerate conflict and psychological distress), can influence the post-transplant morbidity and mortality [10–12].

Regarding LT, the predictive ability of pre-transplant psychiatric and psychological factors is debated.

Herein, we sought to provide an overview of the current knowledge about the psychosocial and psychiatric conditions that can impact the clinical outcome of adult LT recipients proposing a multidisciplinary point of view. Indeed, we conducted a non-systematic literature review considering primarily original studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses (only in English language). Analyzed studies were available on Ovid, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane controlled trials register and/or Web of Science. We did not deepen not-English language papers, book chapters, abstracts, case reports, editorials, non-systematic reviews, studies published before 1990. We used as main key terms “psychosocial status and liver transplant”, “psychiatry and liver transplant”, “liver transplant recipients and outcome”.

2Pre-transplant psychosocial statusA correct organ allocation is mandatory to increase graft and recipient survival [13]. During the pre-LT screening process, social, psychological and psychiatric assessments are usually conducted for excluding major psychiatric illness and for evaluating the potential lack of adherence to clinical and pharmacological recommendations before and after LT [14]. Major psychiatric illness (such as schizophrenia), active illicit drugs use or alcohol consumption in absence of social support, are associated to low compliance representing consolidated contraindications for LT [15]. In particular, active illicit drug and alcohol habit lead to an unacceptable risk of recidivism, non-compliance and graft injury [16]. On the other hand, steadily abstinent, methadone-maintained, opiate-dependent candidates are commonly acceptable candidates [16,17]. Concerning the other psychological conditions such as the mood disorders, it would be important to make an accurate and early diagnosis, to set a therapeutic course and to prospectively evaluate patients as regards their compliance.

The etiology of liver disease can represent a specific risk factor for both impairment of HRQoL and mental distress. In details, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can alter the HRQoL even in absence of advanced cirrhosis showing per se a deleterious impact on both mental health and physical well being [18,19]. HCV positive patients often develop fatigue, irritability, general malaise, abdominal pain, joint pain and headache that definitely may weaken both general psychological status and HRQoL [20,21]. HCV can negatively modify also the post-LT condition since HCV positive recipients can develop higher rates of depression symptoms at Brief Symptoms Inventory in comparison with other etiologies [22]. Also subjects with alcohol-related liver disease deserve specific selection. In fact, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is associated in about one third of cases with a mood disorder [23,24]. However, it has been suggested that etiology of liver disease is not the main predictor of altered mental status during the staying on waitlist. Remarkably, the presence of negative and passive coping behavior such as an acceptance-resignation strategy represents a leading cause of mental health impairment. Notably, it determines an altered insight of physical functioning and a decrease of global HRQoL [25].

3Impact of psychological distress on post-transplant outcomeIn the context of organ transplantation, depression is surely the most studied mental disease. In the general population, depression (major depressive disorder or dysthymia) is not only a significant determinant of HRQoL impairment [26] but also a relevant predictor of increased medical burden, health costs and poor treatment adherence [27]. Few data are available about pre-transplant psychological factors as predictors of post-LT outcome and particularly on the possible role of pre-LT depression. However, depression is a relevant clinical problem for patients into the transplant program since 15% of candidates waiting for LT show one or more depressive symptoms [28]. Markedly, Kanwal et al. [29] showed that cirrhotic patients with low HRQoL display worse survival respect to the others, even after adjusting for noteworthy factors such as model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) [29]. In particular, authors demonstrated that different levels of Short Form Liver Disease Quality of Life independently predicted mortality. In fact, patients with scores 2 standard deviations above the mean were about 60% (relative risk, 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.41–0.43) less likely to die in comparison with subjects with average HRQoL. Interestingly, patients with pre-LT depression-like symptoms show high risk of post-LT overt depression (measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) [30]. The young age, the lack of spouse and unemployment represent consolidated predictors of post-transplant depression (graduated according to Patient Health Questionnaire-9) [31]. Also other psychological alterations can influence the post-LT mental status. In fact, raised levels of anxiety and neuroticism (defined as a tendency toward anxiety, self-doubt, depression, and shyness) at pre-LT evaluation were associated with worse psychosocial outcome at 1 year from the transplant [32]. More in general, pre-transplant vulnerability (characterized by lack of coherence, optimism and social support and presence of anxiety and/or depression) can predict the onset of mental status distress after transplantation [33]. Furthermore, pre-LT maladaptive coping mechanism, deregulation, hostility, lack of effective social support, correlated with worse HRQoL and mood at 1 year after transplant [34]. Corruble et al. [35] analyzed pre-LT psychological assessment of 339 patients exploring its possible association with graft failure and post-LT 18 month-mortality. Surprisingly, the authors demonstrated with both bivariate and multivariate analysis, that presence of depressive symptoms on waitlist was associated to 3- to 4-fold decreased risk of graft failure and mortality, independently from all the other main drivers of post-LT outcome such as age, gender or primary liver disease diagnosis. Interestingly, as possible explanation, the authors suggested that transplant recipients with depressive symptoms might be better competent to face psychological distress that commonly arises after transplant.

On the other hand, Rogal et al. [36] reported that pre-LT depression (including minor and major depression, adjustment disorder, and mixed anxiety and depression) did not directly influence the clinical outcome in terms of graft rejection and mortality. However, patients with depression needed more often psychiatric support in the post-LT period (37% vs. 18%). Furthermore, patients on effective antidepressant therapy at the time of surgery showed a lower rate of acute cellular rejection in comparison with candidates who did not take antidepressants (13% vs. 40%). Indeed, the authors demonstrated that an underestimated or untreated depression could negatively influence the post-LT clinical course. The same authors [37] reinforced the message analyzing the long-term transplant outcome (10 years after LT). Depressed recipients with unsuccessfully treated depression (assessed with Beck Depression Inventory) revealed an all-cause mortality rate of 68% while mortality percentage was substantially lower in subjects under effective antidepressants (48%) and in non-depressed ones (44%). Notably, the adequacy of antidepressant treatment was assessed with The Antidepressant Treatment History Form (range 1–5). Medication dose administered for at least 4 weeks with a score ≥3 was considered satisfactory. Interestingly, the authors proved that the efficient treatment of psychiatric condition might influence patient survival more than the consolidated predictors such as HCV clearance, low MELD score and young donor age.

Telles-Correia et al. [38] examined data of 150 LT recipients showing that pre-transplant solid social support was a strong predictor of 1-year post-LT survival while presence of neuroticism during the waitlist permanence was significantly and independently associated with higher post-LT mortality. According to the reported data, social support and neuroticism seem to have major influence on patient outcome than severity of liver disease.

4Immunosuppressive drug adherenceThe lack of compliance can negatively alter both HRQoL and clinical outcome of transplant recipients being a major risk factor for graft rejection [39]. An adequate selection of candidates to organ transplant forecasts the assessment of the compliant behavior before surgery [39]. Notably, a psychotherapeutic support program for candidates to LT might increase the compliance to medical issues leading to a more effective adaption to the transplant itself [40]. However, data about the predictive ability of pre-LT psychosocial condition regarding the immunosuppressive therapy adherence are discordant. Rodrigue et al. [41] analyzed the immunosuppression adherence and health status of 236 LT recipients during their first two years after LT. Thirty-five percent of patients were missed-dose non-adherent, 30% reported 1 or more 24-hour immunosuppression holidays in the past 6 months and 14% were altered-dose non-adherent. Notably, the pre-LT mood disorder and social support instability increased the risk of non-adherence. More recently, Lieber et al. [42] evaluated whether the psychosocial assessment before LT could aim to detect patients at major risk of non-adherence. The study comprised 248 LT recipients observed at least 1 year after surgery. Similarly to the previous study, the authors described high rates of inadequate compliance (50%). However, none of the pre-LT psychosocial patterns were able to foresee non-adherence or rejection.

5Role of psychologist in the transplant processThe pre-LT psychological assessment might be important for the evaluation of LT candidacy and for the improvement of post-LT clinical outcome [14]. Candidates on waitlist often develop fears related to transplant and depression symptoms that can negatively influence functional capacity, social context, economic situation, global mental health status and post-LT clinical outcome [43]. In particular, the presence of pre-LT mood disorder, the lack of social support, the substance misuse and the alcohol habit, seem to be associated to post-transplant mental and physical morbidity [44]. In this context, targeted psychological intervention can contribute to favor the recovery process improving HRQoL and observance to clinical recommendations and treatment [43]. Psychosocial interventions can help patients with end-stage liver disease to reduce illness-related fear but also symptoms of anxiety and depression and global HRQoL [45].

Remarkably, the psychological intervention has to be fully integrated in a multidisciplinary clinical approach with the involvement of all the main professional figures of the LT process (primarily surgeons, hepatologists and psychologists) who should collaborate, interchange information and face together the main clinical events of the transplant process, from the pre-listing evaluation until the post-LT period. Members of multidisciplinary team might perform joint visit and ward round to reinforce the clinical exchange. In fact, only a global intervention results to be effective as diagnostic and therapeutic tool [39]. The psychological support and care can be instruments for early diagnosis and quick treatment but also elements of empathy toward the entire clinical transplant team. In fact, the medical approach alone might favor the onset of negative psychological patient's reactions such as depression as sign of somatization [43]. One of the main aims of the transplant psychologist should be the achievement of active coping strategy. As reported, coping can be defined as all abilities used to face stressful situations. Notably, the psychological concept of coping has been already applied in the field of transplant psychology. The assessment of coping strategies should be explored during the transplant process encouraging patients to use of action-oriented methods and discourage the passive reactions that definitely can negatively impact the prognosis [46,47]. Telles-Correia et al. [38] analyzed the influence of psychiatric and psychosocial factors on 150 LT recipients demonstrating that active coping is a relevant predictor of short hospitalization after LT. Active coping, social support and multidisciplinary approach might help patients to obtain a psychological positive change after LT that in other transplant contexts, seems to be possible [48]. The relevance of social support has been confirmed in many transplant settings including LT. In fact, LT recipients who have relatives with symptoms of anxiety and/or depression decrease their HRQoL at 1 year from the transplant [49]. Interestingly, LT candidates with anxious family members tend to use to a lesser extent effective coping strategies such as active fighting, self-control/emotional control and seeking for social support [50]. Caregivers of LT candidates often show psychological difficulties and stressors such as doubts about emergency situations (42.6%), mood swings (29.5%), food and medications (27.9%). In general, a quarter of the caregivers feel themselves inadequate for their role. Seeing the relevance of the social support, sustenance measures and caregiver-dedicated training should be implemented in all transplant centers [51].

Remarkably, multidisciplinary team should help patients to develop a positive attitude toward transplant process. In particular, transplant recipients should get a post-traumatic growth that represents a positive psychological change consequent to an adverse life experience. Notably, Pérez-San-Gregorio et al. [46] analyzed the predictors of post-traumatic growth (assessed with Posttraumatic Growth Inventory) in LT recipients demonstrating that active coping, instrumental support, emotional support and acceptance, were associated to a major growth. Transplant surely is a stressful event but at the same time it can lead to major confidence in own capacities particularly regarding the management of difficulties. Organ transplantation can favor the aptitude to organize and plan the everyday activities and facilitate new adaptive strategies [52].

Again Pérez-San-Gregorio et al. [53] studied the post-traumatic growth of caregivers of LT recipients. The authors, using as in the previous study the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, analyzed 218 family members. Interestingly, also in the caregivers, positive coping strategy correlated with a major post-traumatic growth.

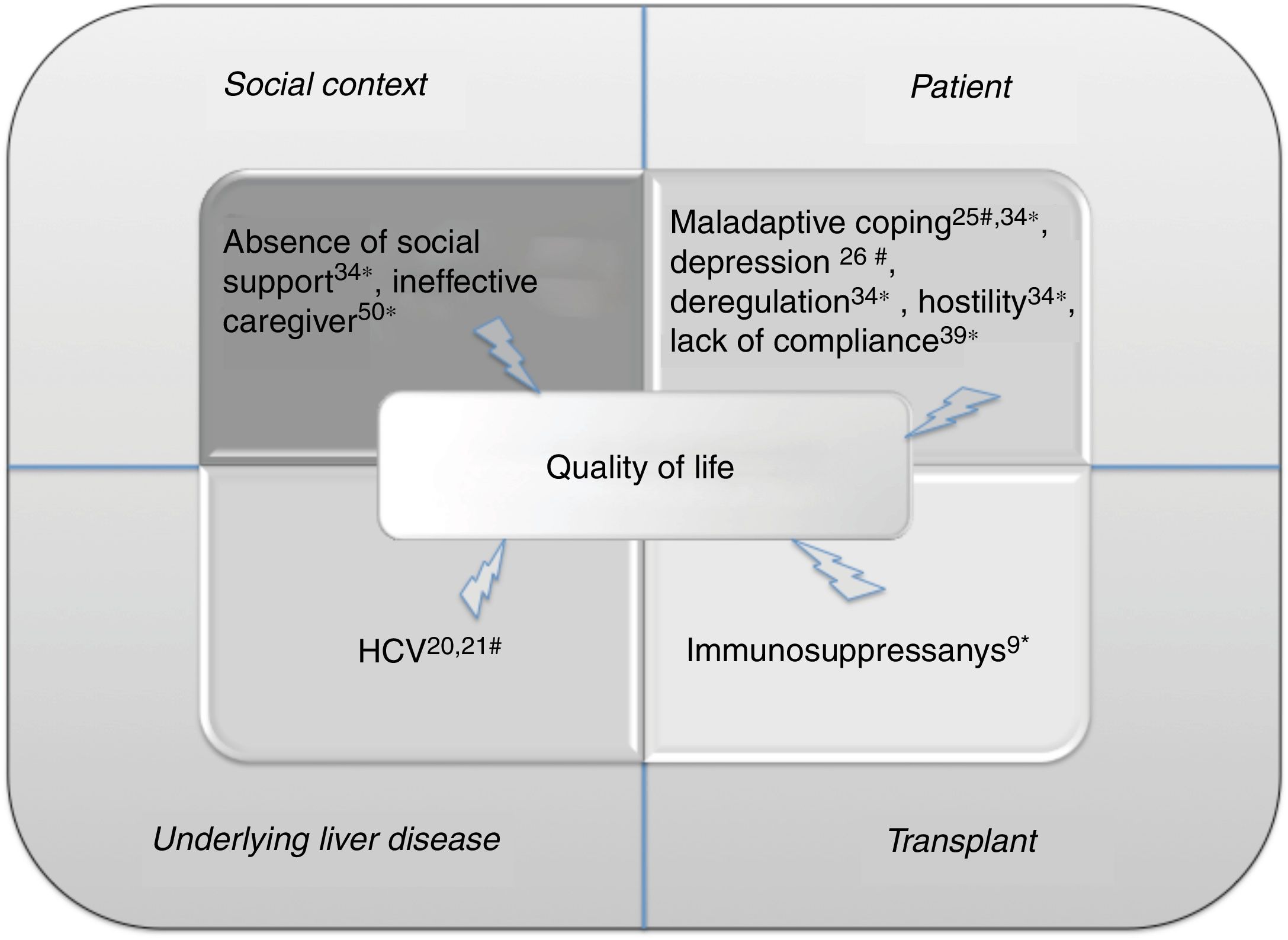

6ConclusionsAchievement of survival benefit and return to satisfying HRQoL represent main goals of organ transplantation (in Fig. 1, we summarized the main factors influencing the HRQoL during the transplant process). Transplant recipients should reach the health status they had before the onset of liver disease with virtuous balance between graft functionality and recipient physical integrity [54]. The multidisciplinary team might represent a noteworthy element to get these purposes. Notably, the multidisciplinary team guarantees the global attitude that is definitely the only efficient diagnostic and therapeutic approach. As recently demonstrated, in patients transplanted for AUD, the multidisciplinary approach might favor detection of early alcohol use recurrence improving patient survival [55].

Main factors influencing the quality of life of patients during the transplant process. Each factor has been associated to reference number. We detected the following main macro categories: social context, patient psychological patterns, underlying liver disease and features correlated to transplant.

Hashtag indicates the effect on pre-transplant quality of life; asterisk, on post-transplant quality of life.

HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Seeing the relationship between psychosocial patterns and clinical outcome, the multidisciplinary approach and the development of biopsychosocial model represent the only reasonable ways to obtain a global benefit for patients [56].

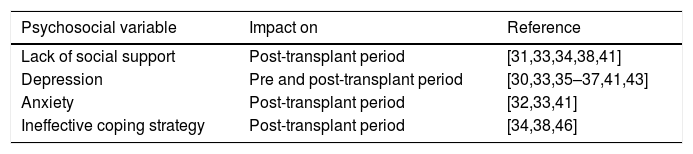

Multidisciplinary team should include expert and specifically formed psychologist and psychiatrist for early diagnosis and effective treatment of pre-transplant mental illness. Markedly, psychological status of LT candidates might influence post-LT adherence, HRQoL and global clinical outcome. Many psychosocial factors can influence the transplant process as summarized in Table 1.

Psychosocial conditions influencing the clinical outcome of patients during the liver transplant process.

| Psychosocial variable | Impact on | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of social support | Post-transplant period | [31,33,34,38,41] |

| Depression | Pre and post-transplant period | [30,33,35–37,41,43] |

| Anxiety | Post-transplant period | [32,33,41] |

| Ineffective coping strategy | Post-transplant period | [34,38,46] |

Recently, Schneekloth et al. [57] underlined the importance of the pre-LT psychological assessment. The authors evaluated the pre-LT psychosocial variables of all North-American LT recipients (from 2000 to 2012) in relationship with post-LT mortality. Pre-LT psychosocial screening scales were able to recognize psychosocial burden foreseeing post-LT outcomes. In particular, female LT recipients with lower Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation scores and alcoholic liver disease, showed a higher post-transplant mortality.

Depression is the most studied pre-LT psychological condition. Interestingly, transplant recipients with an inefficiently treated depression, showed a worst overall survival in respect to subjects under effective antidepressants or non-depressed patients [37]. Dew et al. [58] developed an important systematic review and meta-analysis including twenty-seven studies about LT but also heart, kidney, lung, pancreas transplant. Notably, depression but not anxiety increased the relative risk of post-transplant mortality by 65%.

Few data are available about the possibility to predict the lack of adherence to immunosuppressive regimens. In this regard, De Geest et al. [59] recently demonstrated that pre-transplant medication non-adherence was associated with threefold higher odds of post-transplant immunosuppression non-adherence. These data, coming from liver, renal, heart and lung transplant recipients, showed the importance of early detection of non-compliance. The authors indirectly confirmed the relevance of active multidisciplinary team that definitely should monitor and follow patients by a clinical and psychosocial point of view in all the transplant phases. In fact, the authors suggested the need of planning early adherence-supporting interventions.

It has to be underlined that the lack of compliance can negatively impact both HRQoL and clinical outcome of transplant recipients [39] and that, in general, a psychological support program targeted to the pre-LT period, might increase the compliance of transplanted patients [40].

In conclusion, the multidisciplinary team should perform a quick and effective evaluation of social support, an adequate training about LT process, and an early psychological/psychiatric diagnosis. The multidisciplinary team should favor the development of virtuous mechanisms such as active coping that, together with valid social support and whole multidisciplinary approach, can improve the clinical outcome of transplant recipients. All patients within transplant program can benefit from psychological support with the aim of transforming the traumatic experience of LT in a personal psychological growth.

7Future perspectivesActually, there are not evidences about the opportunity to use a specific psychological approach for a particular phase of the transplant process and seeing the inhomogeneity between patients waiting for LT, to plan a study would be very difficult. In fact, candidates to LT show different age at the time of LT, can be affected by AUD or not, can develop a primary liver cancer or not, can have a long staying on waitlist or not (from hours to years). Nevertheless, we can make the following suggestions potentially useful for planning further studies: (a) any psychological approach useful to obtain active coping strategy might be considered valuable; (b) seeing the importance of social support, family therapy might be helpful; (c) in general population group or self-help group therapy seem to be beneficial for patients with history of illicit drug use or AUD [60]; indeed, also in the transplant context, these kind of approaches might lead to significant results.AbbreviationsPTSD post-traumatic stress disorder liver transplantation health-related quality of life hepatitis C virus alcohol use disorder model for end-stage liver disease

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.