This study aimed to compare the therapeutic efficacy of metformin and other anti-hyperglycemic agents in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

MaterialsA systematic electronic search on keywords including HCC and different anti-hyperglycemic agents was performed through electronic databases including Medline and EMBASE. The primary outcome was the overall survival (OS). The secondary outcomes were the recurrence-free survival (RFS) and progression-free survival (PFS).

ResultsSix retrospective cohort studies were included for analysis: Four studies with curative treatment for HCC (618 patients with metformin and 532 patients with other anti-hyperglycemic agents) and two studies with non-curative treatment for HCC (92 patients with metformin and 57 patients with other anti-hyperglycemic agents). Treatment with metformin was associated with significantly longer OS (OR1yr=2.62, 95%CI: 1.76–3.90; OR3yr=3.14, 95%CI: 2.33–4.24; OR5yr=3.31, 95%CI: 2.39–4.59, all P<0.00001) and RFS (OR1yr=2.52, 95%CI: 1.84–3.44; OR3yr=2.87, 95%CI: 2.15–3.84; all P<0.00001; and OR5yr=2.26, 95%CI: 0.94–5.45, P=0.07) rates vs. those of other anti-hyperglycemic agents after curative therapies for HCC. However, both of the two studies reported that following non-curative HCC treatment, there were no significant differences in the OS and PFS rates between the metformin and non-metformin groups (I2>50%).

ConclusionsMetformin significantly prolonged the survival of HCC patients with T2D after the curative treatment of HCC. However, the efficacy of metformin needs to be further determined after non-curative therapies for HCC patients with T2D.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Patients with very early and early stage HCC can receive curative treatment in the form of a hepatic resection or radiofrequency ablation therapy. While patients with medium, advanced, or end stage HCC generally receive non-curative treatment, including transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, targeted therapies, and traditional Chinese medicine [2]. However, the prognosis of HCC after these therapies is not satisfactory due to a high incidence of recurrence and progression [3,4].

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) has been proven to be a risk factor for HCC development worldwide [5]. Furthermore, T2D can promote the recurrence and progression of HCC after curative and non-curative treatments, although the mechanisms remain unclear [6]. Previous studies, including randomized controlled trials and multicenter retrospective studies, have reported that treatment with metformin or other anti-hyperglycemic drugs decreases the risk of HCC development in T2D patients [7–9]. However, a few retrospective cohort studies have revealed contradictory effects for anti-hyperglycemic drugs on overall survival and recurrence/progression of HCC in HCC patients with T2D [10–13]. Although a meta-analysis reported that metformin increased the overall survival rate of HCC patients with diabetes, the study contained clinical data with a high heterogeneity (I2=82.9%) [14]. Therefore, there is currently no definitive clinical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of metformin and other anti-hyperglycemic treatments for HCC patients with T2D.

This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the effects of metformin and other anti-hyperglycemic agents on the overall survival, recurrence-free survival, and progression-free survival of HCC patients with T2D.

2Materials and methods2.1Search strategyWe searched all of the articles in Medline, Embase, and Wanfang Data up until January 10, 2019 using keywords (metformin OR dimethylguanylguanidine) AND (carcinoma, hepatocellular OR hepatocellular carcinoma OR hepatoma).

2.2Inclusion and exclusion criteriaWe included all randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case–control studies if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) focused on patients with confirmed HCC and T2D; (2) patients received T2D treatment with metformin and/or any other anti-hyperglycemic agent(s) after initial treatment for HCC; and (3) included data about HCC recurrence, disease progression, and/or mortality during the follow-up period. Publications concerning the effects of anti-hyperglycemic agents after curative or non-curative treatments for HCC were included in this analysis. The following studies were excluded: (1) non-clinical studies, animal studies, conference abstracts, or reviews; (2) preventive studies regarding metformin or other anti-hyperglycemic agents on HCC development; and (3) clinical studies without complete clinical data on overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), and progression-free survival (PFS).

The primary outcome was OS after curative or non-curative treatment for HCC. The secondary outcomes were RFS after curative treatment of HCC or PFS after non-curative treatment of HCC.

2.3Data extraction and validity assessmentThe available articles were reviewed and selected according to the criteria. Useful data were extracted by two investigators (JZ and YK), independently, using a standardized data extraction form that included the following information: Name of the first author, study country or region, publication year, types of anti-hyperglycemic drugs, corresponding dose and course, number of patients, number of males and females, mean age, number of hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, Child–Pugh score, tumor characteristics (number and size), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, fasting glucose, and types of curative or non-curative treatments for HCC. In cases of discrepancies between the investigators during the process of article selection and data extraction, a third investigator (XFL) participated in the discussion to make the final decision. The quality of each study was assessed according to the STROBE checklist [15].

2.4Statistical analysisCombining the multiple outcome measures of this meta-analysis was performed using Revman 5.3 (the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were used to compare outcome variants between the metformin and non-metformin groups. An OR <1 meant a lower rate of outcome in the treatment group. Statistic heterogeneity was assessed by I2. The combined estimates were calculated and pooled under a fixed-effects model when there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2<50%). Otherwise, the estimates were combined by a random-effects model or the results were summarized without being combined. Sensitivity analyses were also performed as a possible evaluation of the existing heterogeneity. Publication biases were evaluated by funnel plot. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

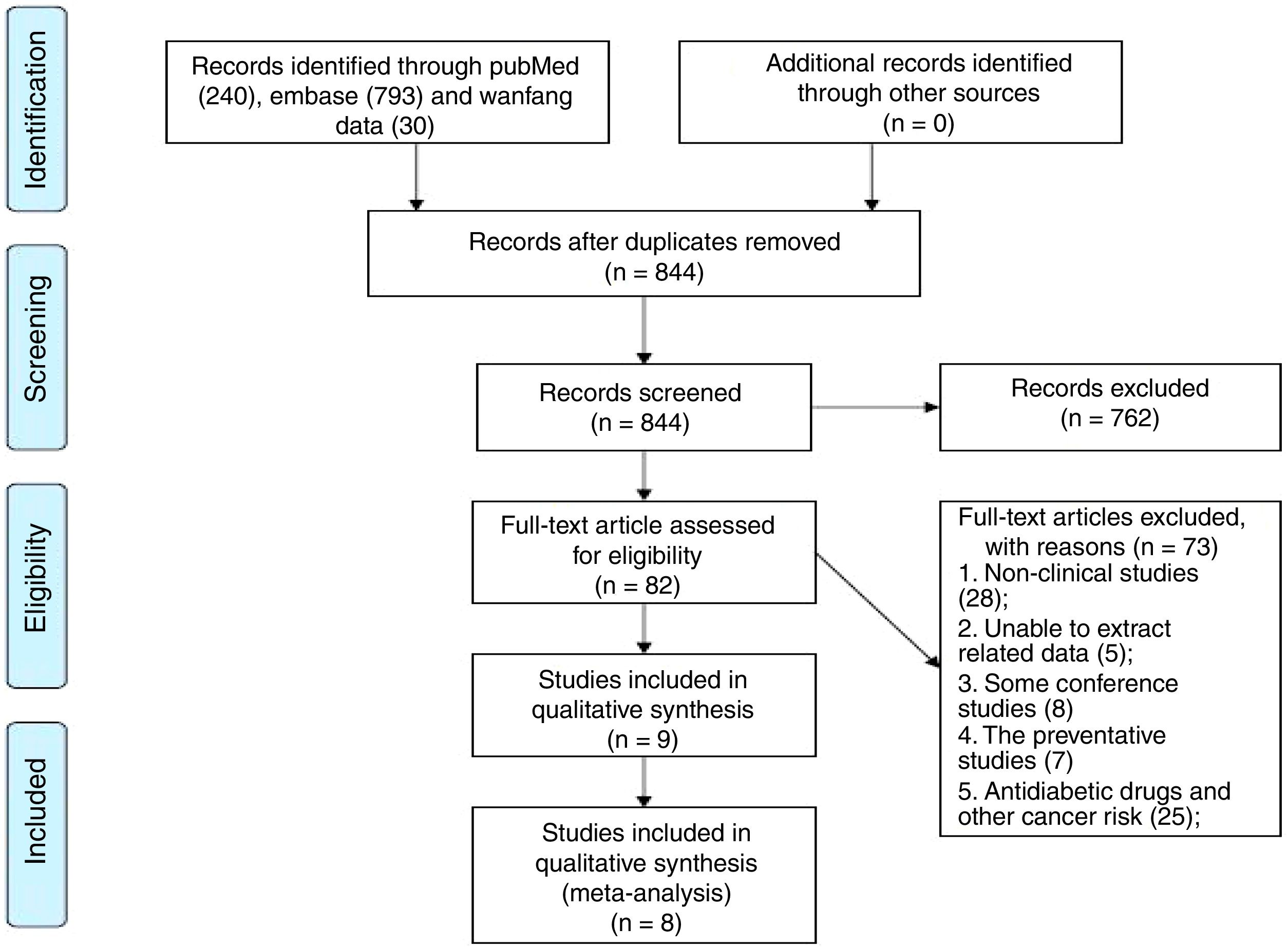

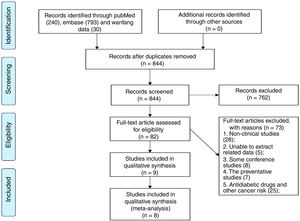

3Results3.1Characteristics of studiesOne thousand and sixty-three pieces of abstracts were found from the literature search using the specific keywords, and 844 were identified after the removal of duplicates. A total of 82 abstracts fulfilled the inclusion criteria. From these 82 publications, 73 studies were excluded following analysis of the full text: 28 reviews, editorials, or experimental articles from rodent studies, eight conference abstracts, five studies without clinical outcomes following anti-hyperglycemic therapy, seven studies which centered on the HCC-preventative effects of an anti-hyperglycemic therapy, and 25 studies on the preventative effects of anti-hyperglycemic therapies for non-HCC cancers. There were two studies in the remaining nine that were performed by the same team and had the same theme, we chose the study with the most patients [16,17]. Finally, eight retrospective cohort studies were included in this preliminary meta-analysis [10–13,17–20] (Fig. 1).

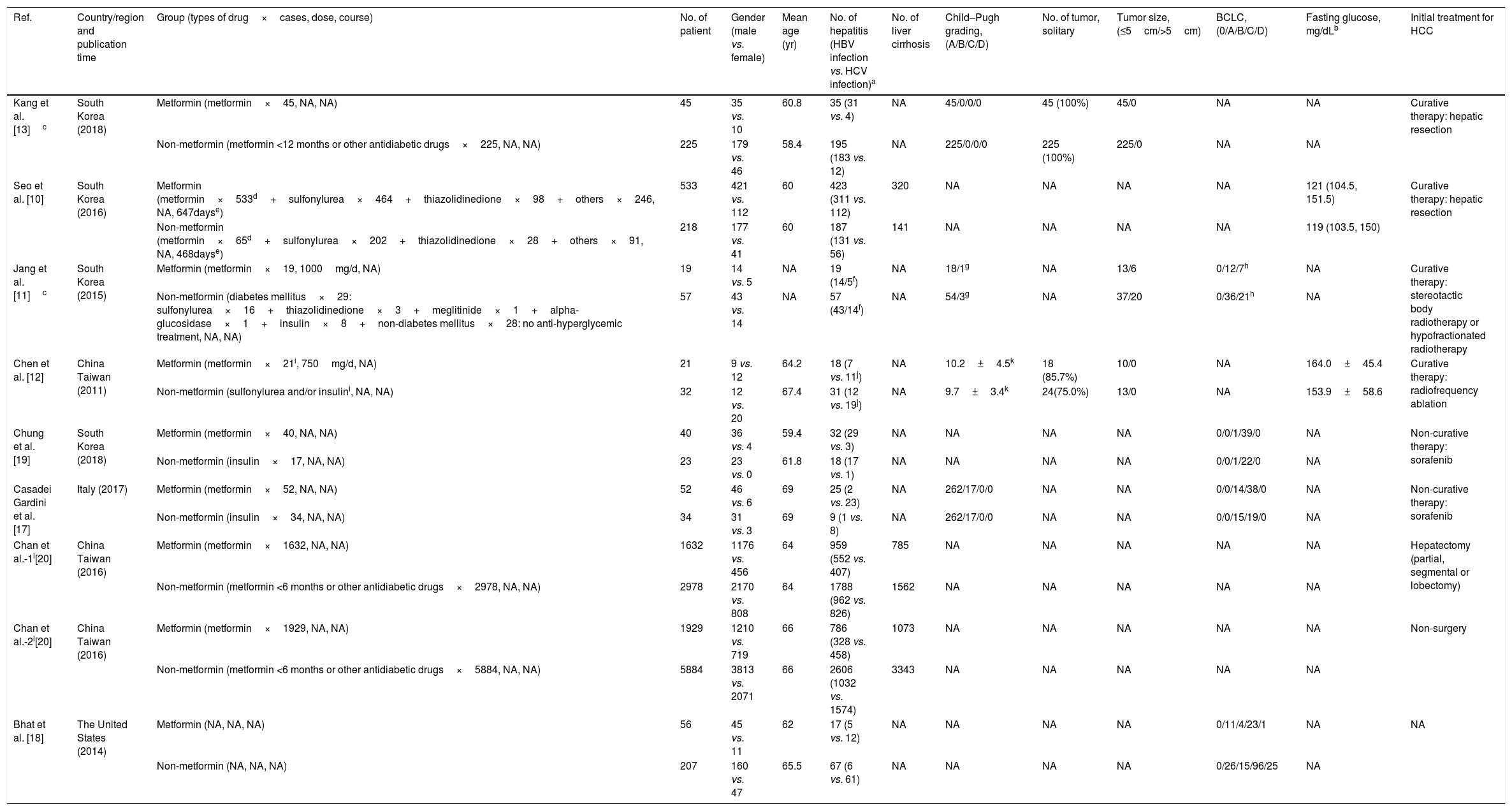

A total of 13,985 patients from eight studies were included: 4327 HCC participants with T2D received metformin therapy in the metformin group, with a further 9658 belonging to the non-metformin group [10–13,17–20]. The choice of hypoglycemic drugs for T2D was made according to the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes from the American Diabetes Association [12]. In the metformin group, all patients were treated with metformin in a dose range of 250–2000mg/day for more than 3 months to control the T2D. In the non-metformin group, most patients received other anti-hyperglycemic agents, such as sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, alpha-glucosidase, and insulin, and three studies included patients who had used a short course of metformin (<6 months [20] and <3 [10,18]). For the initial treatment of HCC, patients from three of the studies received curative HCC treatments, including hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation therapy [10,12,13]; patients from one study received complete tumor necrosis after stereotactic body radiotherapy or hypofractionated radiation therapy [11]; patients from one study received surgical or non-surgical treatment, but the authors did not distinguish between curative or non-curative treatment [20]; patients in another two studies received non-curative HCC targeted therapy with sorafenib [17,19]; and one study did not detail the initial treatment for the HCC [18]. Baseline comparisons between the metformin and non-metformin groups were performed in eight studies [10–13,17–20]. There were no significant differences in age, gender, hepatitis virus infection, presence of cirrhosis, Child–Pugh grading, tumor staging, fasting glucose, and the initial treatment of HCC between both of the groups. The characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with T2D before initial treatment of HCC.

| Ref. | Country/region and publication time | Group (types of drug×cases, dose, course) | No. of patient | Gender (male vs. female) | Mean age (yr) | No. of hepatitis (HBV infection vs. HCV infection)a | No. of liver cirrhosis | Child–Pugh grading, (A/B/C/D) | No. of tumor, solitary | Tumor size, (≤5cm/>5cm) | BCLC, (0/A/B/C/D) | Fasting glucose, mg/dLb | Initial treatment for HCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang et al. [13]c | South Korea (2018) | Metformin (metformin×45, NA, NA) | 45 | 35 vs. 10 | 60.8 | 35 (31 vs. 4) | NA | 45/0/0/0 | 45 (100%) | 45/0 | NA | NA | Curative therapy: hepatic resection |

| Non-metformin (metformin <12 months or other antidiabetic drugs×225, NA, NA) | 225 | 179 vs. 46 | 58.4 | 195 (183 vs. 12) | NA | 225/0/0/0 | 225 (100%) | 225/0 | NA | NA | |||

| Seo et al. [10] | South Korea (2016) | Metformin (metformin×533d+sulfonylurea×464+thiazolidinedione×98+others×246, NA, 647dayse) | 533 | 421 vs. 112 | 60 | 423 (311 vs. 112) | 320 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 121 (104.5, 151.5) | Curative therapy: hepatic resection |

| Non-metformin (metformin×65d+sulfonylurea×202+thiazolidinedione×28+others×91, NA, 468dayse) | 218 | 177 vs. 41 | 60 | 187 (131 vs. 56) | 141 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 119 (103.5, 150) | |||

| Jang et al. [11]c | South Korea (2015) | Metformin (metformin×19, 1000mg/d, NA) | 19 | 14 vs. 5 | NA | 19 (14/5f) | NA | 18/1g | NA | 13/6 | 0/12/7h | NA | Curative therapy: stereotactic body radiotherapy or hypofractionated radiotherapy |

| Non-metformin (diabetes mellitus×29: sulfonylurea×16+thiazolidinedione×3+meglitinide×1+alpha-glucosidase×1+insulin×8+non-diabetes mellitus×28: no anti-hyperglycemic treatment, NA, NA) | 57 | 43 vs. 14 | NA | 57 (43/14f) | NA | 54/3g | NA | 37/20 | 0/36/21h | NA | |||

| Chen et al. [12] | China Taiwan (2011) | Metformin (metformin×21i, 750mg/d, NA) | 21 | 9 vs. 12 | 64.2 | 18 (7 vs. 11j) | NA | 10.2±4.5k | 18 (85.7%) | 10/0 | NA | 164.0±45.4 | Curative therapy: radiofrequency ablation |

| Non-metformin (sulfonylurea and/or insulini, NA, NA) | 32 | 12 vs. 20 | 67.4 | 31 (12 vs. 19j) | NA | 9.7±3.4k | 24(75.0%) | 13/0 | NA | 153.9±58.6 | |||

| Chung et al. [19] | South Korea (2018) | Metformin (metformin×40, NA, NA) | 40 | 36 vs. 4 | 59.4 | 32 (29 vs. 3) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/0/1/39/0 | NA | Non-curative therapy: sorafenib |

| Non-metformin (insulin×17, NA, NA) | 23 | 23 vs. 0 | 61.8 | 18 (17 vs. 1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/0/1/22/0 | NA | |||

| Casadei Gardini et al. [17] | Italy (2017) | Metformin (metformin×52, NA, NA) | 52 | 46 vs. 6 | 69 | 25 (2 vs. 23) | NA | 262/17/0/0 | NA | NA | 0/0/14/38/0 | NA | Non-curative therapy: sorafenib |

| Non-metformin (insulin×34, NA, NA) | 34 | 31 vs. 3 | 69 | 9 (1 vs. 8) | NA | 262/17/0/0 | NA | NA | 0/0/15/19/0 | NA | |||

| Chan et al.-1l[20] | China Taiwan (2016) | Metformin (metformin×1632, NA, NA) | 1632 | 1176 vs. 456 | 64 | 959 (552 vs. 407) | 785 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Hepatectomy (partial, segmental or lobectomy) |

| Non-metformin (metformin <6 months or other antidiabetic drugs×2978, NA, NA) | 2978 | 2170 vs. 808 | 64 | 1788 (962 vs. 826) | 1562 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Chan et al.-2l[20] | China Taiwan (2016) | Metformin (metformin×1929, NA, NA) | 1929 | 1210 vs. 719 | 66 | 786 (328 vs. 458) | 1073 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Non-surgery |

| Non-metformin (metformin <6 months or other antidiabetic drugs×5884, NA, NA) | 5884 | 3813 vs. 2071 | 66 | 2606 (1032 vs. 1574) | 3343 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Bhat et al. [18] | The United States (2014) | Metformin (NA, NA, NA) | 56 | 45 vs. 11 | 62 | 17 (5 vs. 12) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/11/4/23/1 | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin (NA, NA, NA) | 207 | 160 vs. 47 | 65.5 | 67 (6 vs. 61) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/26/15/96/25 | NA |

The criteria of hepatitis B virus HBV and hepatitis C virus HCV infection were not mentioned in original articles.

Using metformin for ≤90 days was categorized as the non-metformin group or >90 days was categorized as the metformin group.

During the follow-up period, insulin resistance, lactic acidosis, or hypoglycemia were not observed in the metformin and non-metformin groups from Chen's study [12], and were also not reported in the other seven studies [10,11,13,17–20]. There was no data regarding the 2-h postprandial blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c levels after anti-hyperglycemic administration. Furthermore, there was no liver function data after anti-hyperglycemic administration.

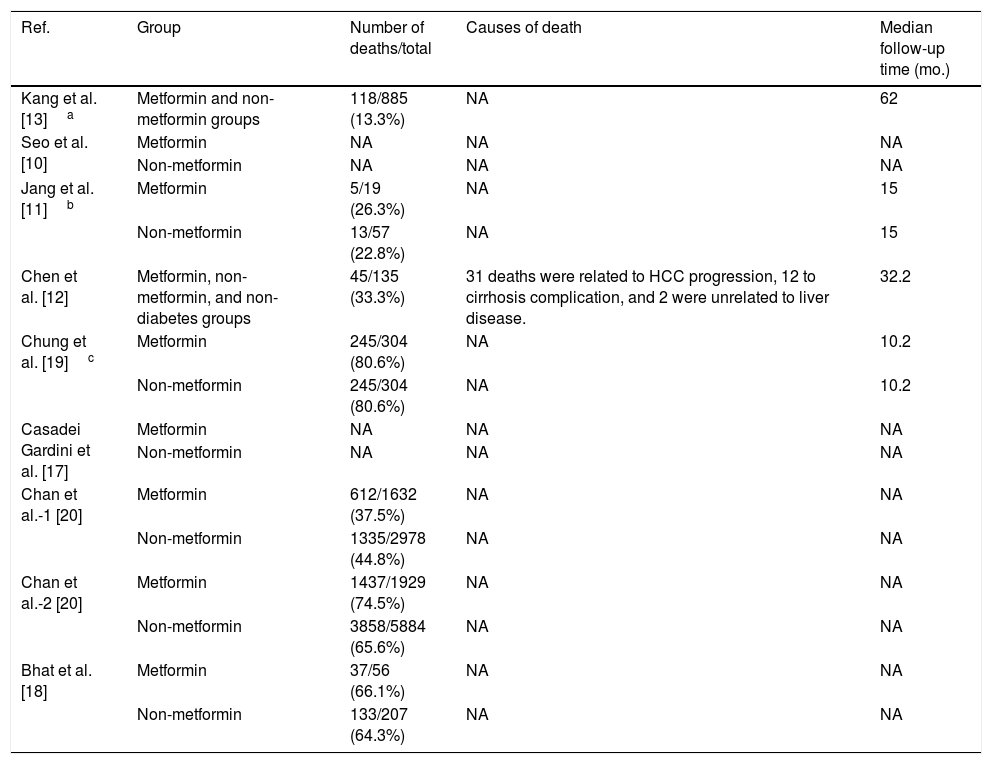

Furthermore, Chen's study showed that 31 patients died due to HCC progression, 12 patients died from severe cirrhotic complications, and two succumbed to extrahepatic diseases. However, the authors did not compare the differences in the causes of death between the metformin and non-metformin groups [12]. The other seven studies did not report on the cause of death for the HCC patients [10,11,13,17–20]. These data are shown in Table 2.

The number and cause of death of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with T2D after metformin or non-metformin treatments.

| Ref. | Group | Number of deaths/total | Causes of death | Median follow-up time (mo.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang et al. [13]a | Metformin and non-metformin groups | 118/885 (13.3%) | NA | 62 |

| Seo et al. [10] | Metformin | NA | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin | NA | NA | NA | |

| Jang et al. [11]b | Metformin | 5/19 (26.3%) | NA | 15 |

| Non-metformin | 13/57 (22.8%) | NA | 15 | |

| Chen et al. [12] | Metformin, non-metformin, and non-diabetes groups | 45/135 (33.3%) | 31 deaths were related to HCC progression, 12 to cirrhosis complication, and 2 were unrelated to liver disease. | 32.2 |

| Chung et al. [19]c | Metformin | 245/304 (80.6%) | NA | 10.2 |

| Non-metformin | 245/304 (80.6%) | NA | 10.2 | |

| Casadei Gardini et al. [17] | Metformin | NA | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin | NA | NA | NA | |

| Chan et al.-1 [20] | Metformin | 612/1632 (37.5%) | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin | 1335/2978 (44.8%) | NA | NA | |

| Chan et al.-2 [20] | Metformin | 1437/1929 (74.5%) | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin | 3858/5884 (65.6%) | NA | NA | |

| Bhat et al. [18] | Metformin | 37/56 (66.1%) | NA | NA |

| Non-metformin | 133/207 (64.3%) | NA | NA |

Combining data from the eight studies [10–13,17–20] showed there was no significant difference in 1yr OS (OR1yr=1.13, 95%CI: 0.43–2.94, P=0.80), but there was a significant difference in 3yr and 5yr OS between the metformin and non-metformin groups (OR3yr=1.83, 95%CI: 1.29–2.60, P=0.0007; OR5yr=1.63, 95%CI: 1.16–2.29, P=0.005). It was notable that these studies showed a medium to high heterogeneity (I2=86%, 76%, and 88%, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 1). We assumed that the heterogeneity mainly resulted from the initial treatment of HCC (curative or non-curative treatment). Accordingly, these studies were stratified according to their curative and non-curative treatments. In the grouping process, Bhat et al. [18] did not indicate the type of initial treatment for the HCC and Chan et al. [20] divided the patients into surgical and non-surgical groups, but did not distinguish between curative and non-curative treatments, and as such the two were excluded from the curative treatment group. Finally, the curative treatment group had four studies [10–13] and the non-curative treatment group had two studies [17,19].

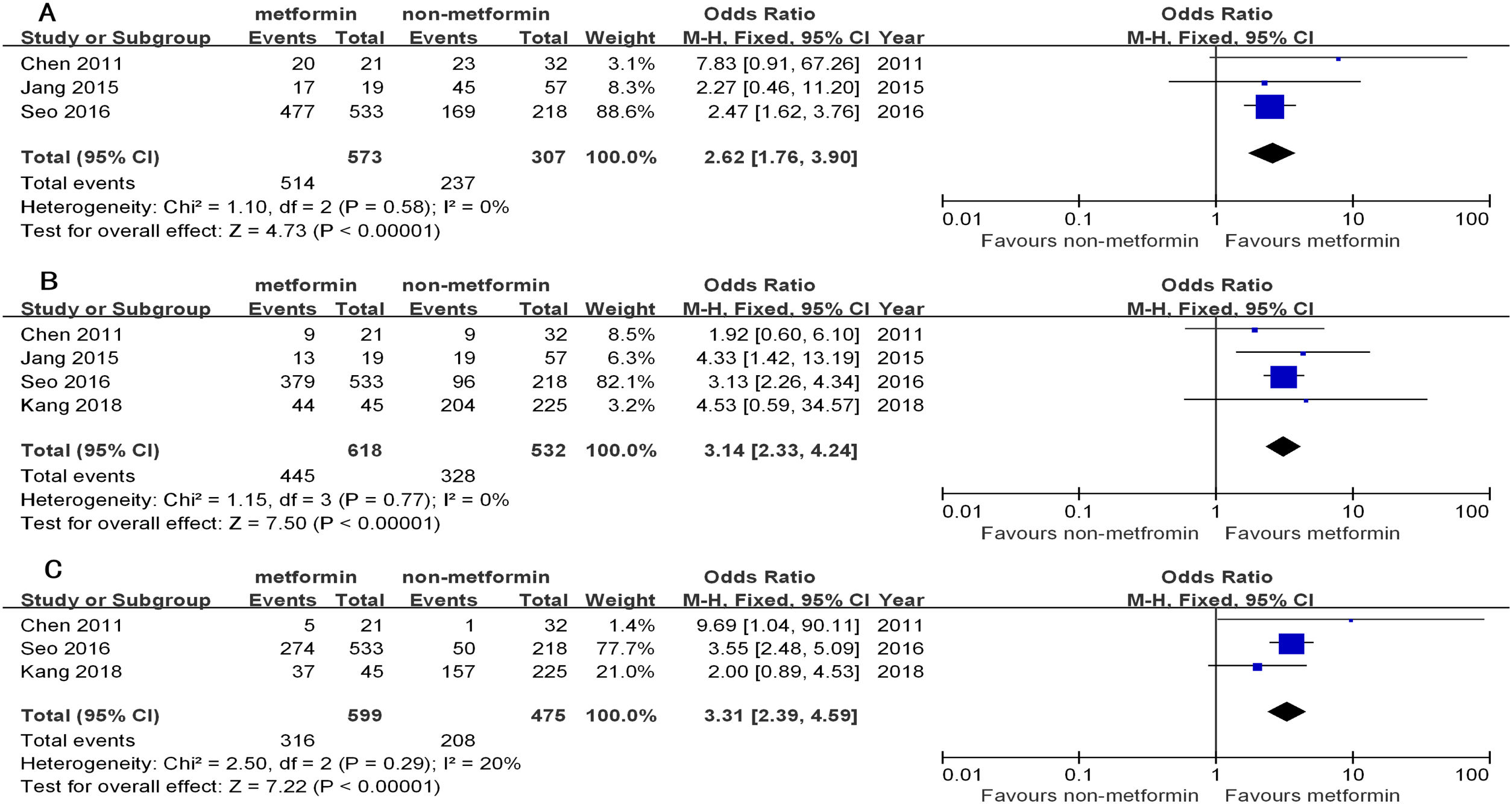

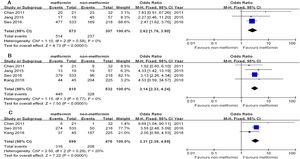

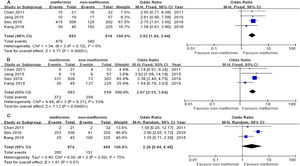

The 1yr, 3yr, and 5yr OS in the patients from the metformin group with curative treatment were significantly longer than that of the non-metformin group (OR1yr=2.62, 95%CI: 1.76–3.90; OR3yr=3.14, 95%CI: 2.33–4.24; OR5yr=3.31, 95%CI: 2.39–4.59, all P<0.00001). There was a low heterogeneity in the curative treatment subgroup (I2=0%, 0%, and 20%, respectively) (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with T2D after metformin or non-metformin treatment for HCC.

| Ref. | Group | No. of patient | 1yr | 3yr | 5yr | Mean survival (mo.) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang et al. [13] | Metformin | 45 | NA | 44 | 37 | 80.4 | 0.028 |

| Non-metformin | 225 | NA | 204 | 157 | 76.8 | ||

| Seo et al. [10] | Metformin | 533 | 477 | 379 | 274 | 92.4 | <0.01 |

| Non-metformin | 218 | 169 | 96 | 50 | 51.6 | ||

| Jang et al. [11]a | Metformin | 19 | 17 | 13 | NA | 30.1 | 0.022 |

| Non-metformin | 57 | 45 | 19 | NA | 18.0 | ||

| Chen et al. [12] | Metformin | 21 | 20 | 9 | 5 | 37.1 | 0.024 |

| Non-metformin | 32 | 23 | 9 | 1 | 24.5 | ||

| Chung et al. [19] | Metformin | 40 | 21 | 4 | NA | 12.1 | 0.96 |

| Non-metformin | 23 | 12 | 0 | NA | 11.8 | ||

| Casadei Gardini et al. [17] | Metformin | 52 | 17 | 2 | NA | 9.3 | 0.0001 |

| Non-metformin | 34 | 27 | 6 | NA | 20.5 | ||

| Chan et al.-1 [20] | Metformin | 1632 | NA | 1519 | 1204 | 96 | <0.0001 |

| Non-metformin | 2978 | NA | 2646 | 1973 | 84 | ||

| Chan et al.-2 [20] | Metformin | 1929 | NA | 1603 | 1000 | 62.4 | 0.4925 |

| Non-metformin | 5884 | NA | 4617 | 2792 | 55.2 | ||

| Bhat et al. [18] | Metformin | 56 | 35 | 25 | 11 | 22.8 | 0.77 |

| Non-metformin | 207 | 137 | 75 | 55 | 32.4 |

The overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) between the metformin and non-metformin groups after curative treatment for HCC. (A) Meta-analysis of the 1yr results (lacking the study by Kang). (B) Meta-analysis of the 3yr results. (C) Meta-analysis of the 5yr results (lacking the study by Jang).

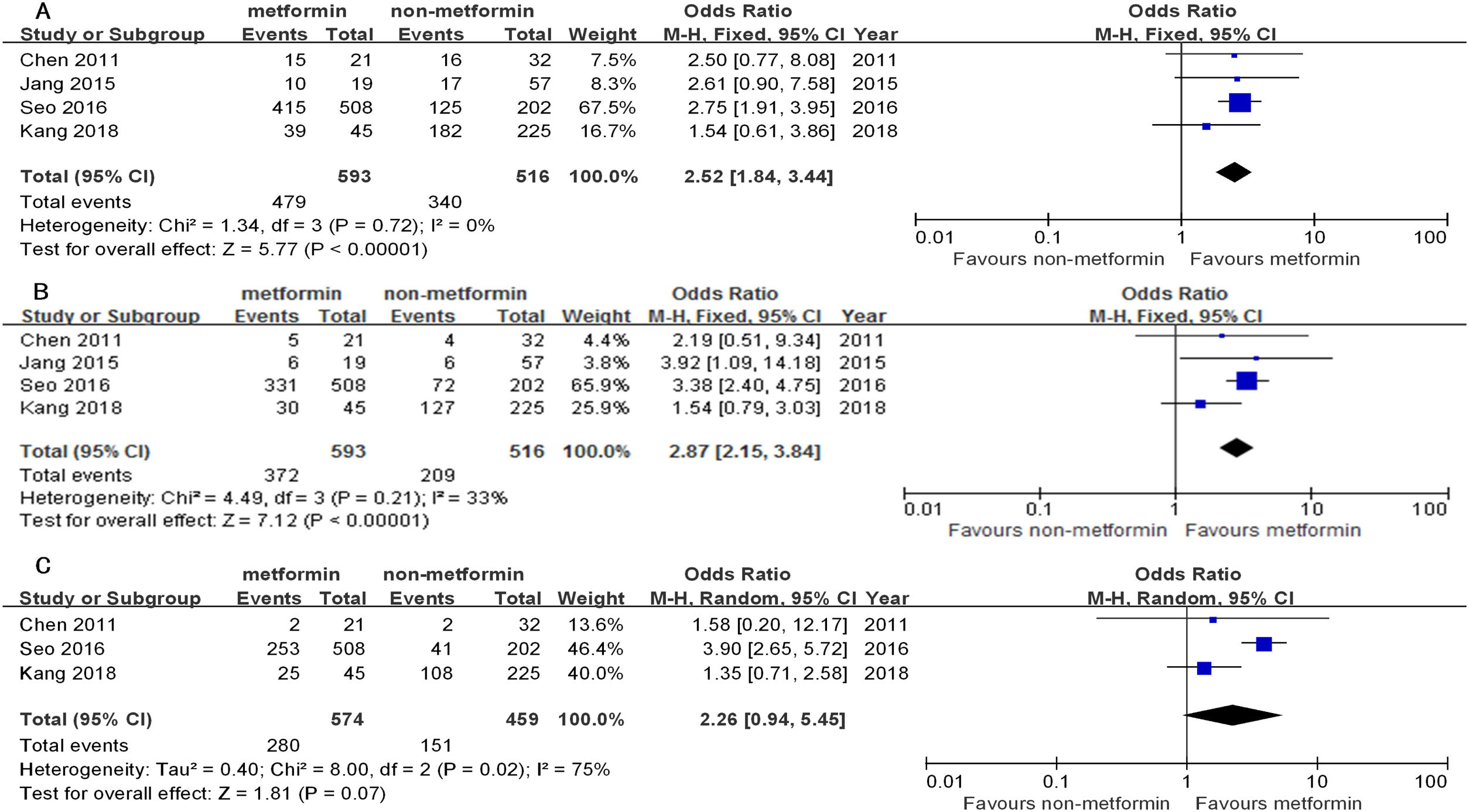

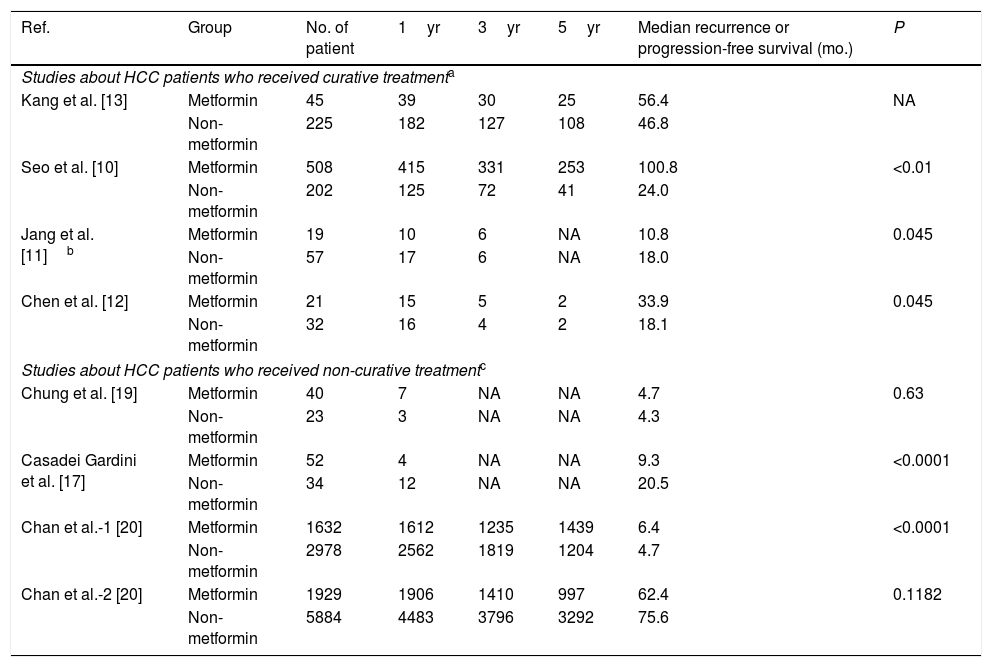

Similarly, the 1yr, 3yr, and 5yr RFS in the patients receiving curative treatment for HCC in the metformin group were significantly longer than the non-metformin group (OR1yr=2.52, 95%CI: 1.84–3.44; OR3yr=2.87, 95%CI: 2.15–3.84; all P<0.00001; and OR5yr=2.26, 95%CI: 0.94–5.45, P=0.07). There was a low–middle heterogeneity between them (I2=0%, 33%, and 75%) (Table 4 and Fig. 3).

Recurrence-free survival or progression-free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with T2D after metformin or non-metformin treatment for HCC.

| Ref. | Group | No. of patient | 1yr | 3yr | 5yr | Median recurrence or progression-free survival (mo.) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies about HCC patients who received curative treatmenta | |||||||

| Kang et al. [13] | Metformin | 45 | 39 | 30 | 25 | 56.4 | NA |

| Non-metformin | 225 | 182 | 127 | 108 | 46.8 | ||

| Seo et al. [10] | Metformin | 508 | 415 | 331 | 253 | 100.8 | <0.01 |

| Non-metformin | 202 | 125 | 72 | 41 | 24.0 | ||

| Jang et al. [11]b | Metformin | 19 | 10 | 6 | NA | 10.8 | 0.045 |

| Non-metformin | 57 | 17 | 6 | NA | 18.0 | ||

| Chen et al. [12] | Metformin | 21 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 33.9 | 0.045 |

| Non-metformin | 32 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 18.1 | ||

| Studies about HCC patients who received non-curative treatmentc | |||||||

| Chung et al. [19] | Metformin | 40 | 7 | NA | NA | 4.7 | 0.63 |

| Non-metformin | 23 | 3 | NA | NA | 4.3 | ||

| Casadei Gardini et al. [17] | Metformin | 52 | 4 | NA | NA | 9.3 | <0.0001 |

| Non-metformin | 34 | 12 | NA | NA | 20.5 | ||

| Chan et al.-1 [20] | Metformin | 1632 | 1612 | 1235 | 1439 | 6.4 | <0.0001 |

| Non-metformin | 2978 | 2562 | 1819 | 1204 | 4.7 | ||

| Chan et al.-2 [20] | Metformin | 1929 | 1906 | 1410 | 997 | 62.4 | 0.1182 |

| Non-metformin | 5884 | 4483 | 3796 | 3292 | 75.6 | ||

Due to the high heterogeneity, there were no conclusive data about OS or PFS in the non-curative subgroup of the two studies [17,19] (Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figure 2). Accordingly, we did a descriptive analysis: The HCC patients from these two studies received sorafenib treatment and all belonged to BCLC B or C. Casadei Gardini et al. [17] reported that patients were treated with sorafenib (400mg twice daily) for HCC until HCC progression, unacceptable toxicity, or death. Chung et al. [19] reported that the patients were treated with sorafenib for a median of 10.2 months (range: 2–76 months), without providing dose clarification.

Additionally, Casadei Gardini et al. [17] reported that the treatment of HCC patients with sorafenib and metformin resulted in a median OS of 6.6 months (95%CI: 4.6–8.7) as compared to 16.6 months (95%CI: 14.5–25.5) with insulin (P=0.0001), and a median PFS of 1.9 months (95%CI: 1.8–2.3) as compared to 8.5 months (95%CI: 5.3–11.4) with insulin (P<0.0001). Chung et al. [19] reported that the median OS of patients on sorafenib treatment was 12.1 months in the metformin group, similar to the 11.8 months of the insulin group (P=0.96), and the median PFS of patients on sorafenib treatment was 4.5 months in the metformin group, similar to the 4.1 months of the insulin group (P=0.63). Therefore, these two studies indicated that treatment with metformin did not significantly prolong the OS and PFS when compared to insulin therapy in HCC patients on sorafenib.

3.5Publication bias assessmentThe publication bias in the study was assessed using a funnel plot of the 3yr OS rate for curative treatment in all of the studies. There was no obverse publication bias in this meta-analysis (Supplementary Figure 3).

4DiscussionThis meta-analysis revealed that anti-hyperglycemic therapies after curative treatment for HCC significantly reduced the risk of cancer recurrence and improved the OS of HCC patients with T2D. This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the efficacy of anti-hyperglycemic drugs on cancer recurrence and OS after the curative treatment of HCC patients with T2D.

Despite advances in surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, there is still no effective adjuvant treatment for preventing HCC recurrence and prolonging the OS. Recent studies have shown that HCC patients with T2D, before or after HCC treatment, are associated with an increased risk of HCC recurrence and a shorter OS [8,9]. These observations have shed some light on the potential role of anti-hyperglycemic therapies in preventing HCC recurrence and prolonging OS. However, this hypothesis has not been demonstrated by any prospective randomized controlled trials. Therefore, this meta-analysis provides important data on the beneficial effects of anti-hyperglycemic therapies on the survival of HCC patients after curative treatment.

In this study, we first combined eight retrospective studies to determine the 1yr, 3yr, and 5yr OS rates [10–13,17–20]. However, they had a high heterogeneity (I2=86%, 76%, and 88%, respectively). This heterogeneity could have stemmed from many factors, including the different durations of the T2D, the different extents of insulin resistance, and the different initial therapies and stages of the HCCs among these studies. To decrease the heterogeneity as much as possible, we subsequently stratified these studies into curative and non-curative treatments for HCC. This stratification decreased the heterogeneity to 0%, 0%, and 20% for 1yr, 3yr, and 5yr OS and 0%, 33%, and 75% for 1yr, 3yr, and 5yr RFS in the curative treatment subgroup. However, the heterogeneity for OS and PFS in the non-curative treatment subgroup did not significantly decrease (I2=88% and 76% for 1yr and 3yr OS, and 81% for 1yr PFS, there were no 5yr OS and 3yr and 5yr PFS reported in the non-curative treatment). The relatively higher heterogeneity of the 5yr RFS may relate to the following three points: (1) the 5yr-sample sizes of the HCC patients decreased; (2) the BCLC staging could have affected the time of HCC recurrence during the follow-up, unfortunately, only one study reported the BCLC-staging data in the curative treatment subgroup [11] and probably different BCLC staging existed among the studies; and (3) the different Child–Pugh grading among the studies might have influenced the recurrence of HCC patients. In the non-curative group, the high heterogeneity may have originated from the difference in the doses and duration of the sorafenib treatment for HCC.

The results from the current study revealed that metformin therapy significantly reduced the risk of HCC recurrence and prolonged OS of HCC patients after curative treatment when compared with other anti-hyperglycemic agents. Clinically, HCC recurrence within 2yr after a curative operation is generally due to primary tumor diffusion. After 2yr, the recurrence is usually is multicentric [21]. Given that metformin treatment decreases the risk of HCC development in T2D patients [22] and inhibits HCC cell proliferation [23], we speculate that metformin therapy may not only inhibit HCC cell proliferation to prevent primary tumor cell diffusion, but also suppress multicentric HCC growth de novo to some extent. Furthermore, since most malignant cells depend on glucose for metabolism, metformin treatment can decrease blood glucose levels and, potentially, inhibit energetic metabolism in HCC cells. Moreover, metformin can control T2D, thereby improving liver function [24] that may contribute to an increase in the OS of HCC patients. However, neither the liver function changes nor the cause of death data for the HCC patients were compared between the different anti-hyperglycemic agents, which should be a focus of further study. On the other hand, through its receptors, insulin can activate the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, which may promote the growth and progression of HCC [25].

In the non-curative group, metformin treatment showed no significant difference compared with other anti-hyperglycemic drugs after non-curative therapy in this population. We speculate that residual tumor and the limited survival time (about 1yr) after non-curative therapy may have hidden the efficacy of the metformin therapy. Furthermore, one basic study indicated that chronic treatment with metformin increased tumor aggressiveness and resistance to sorafenib in advanced HCC [17].

Metformin is a biguanide class of drug. It works by decreasing the glucose production by the liver and increasing the insulin sensitivity of body tissues. Metformin is generally well tolerated. Common side effects of metformin include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain. It has a low risk of causing hypoglycemia. A high blood lactic acid level is a concern if the medication is prescribed inappropriately and in overdose. Insulin is a peptide hormone produced by the pancreatic islet β-cells. It regulates blood glucose levels by promoting the transportation of blood glucose into the liver, fat, and skeletal muscle cells. Furthermore, it strongly inhibits the glucose production and secretion by the liver. Hypoglycemia and increased insulin resistance are major concerns for patients with T2D using insulin. In this meta-analysis, these side effects were not reported following metformin and non-metformin treatments.

The main limitation of this meta-analysis was a lack of data from prospective randomized controlled trials. All of the data in this study were derived from retrospective cohorts, and hence, there was no T2D patients avoiding anti-hyperglycemic therapy. Ideally, a large-scale randomized, placebo-controlled trial is needed to determine the effect of anti-hyperglycemic therapies on HCC patients with T2D after curative HCC treatment. However, it might be considered unethical to perform such a randomized clinical trial, because anti-hyperglycemic therapy is indicated for these patients according to different international guidelines [26,27]. Another limitation of this study was a lack of sufficient data after non-curative treatments for HCC. There were only two studies that indicated that metformin did not improve the OS in these patients [17,19]. Furthermore, information on the baseline severity of T2D, liver disease (cirrhosis, Child–Pugh score, MELD, etc.), HCC stage (BCLC or TNM), and cause of death (liver disease progression, HCC progression, or T2D related and non-liver related complications) were incomplete in some of the studies included in this meta-analysis, and hence, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions.

In conclusion, our data indicates that metformin treatment significantly improves the OS of HCC patients with T2D after curative therapies. Before or after the curative treatment of HCC, patients should be monitored regularly for their blood glucose for consideration of metformin therapy. Further studies should explore the efficacy and safety of metformin in HCC patients without T2D, including HCC patients with insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), as well as HCC patients with advanced or end stage disease.AbbreviationsHCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

T2Dtype 2 diabetes

OSoverall survival

RFSrecurrence-free survival

PFSprogression-free survival

BCLCBarcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

NAFLDnon-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Informed patient consentNot applicable.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 81660399, 81860423]; the Innovative Research Team Project of Yunnan Province [grant number 2015HC033]; the Yunnan Provincial Academician Workstation of Xiaoping Chen [grant number 2017IC018]; the Breeding Program for Major Scientific and Technological Achievements of Kunming Medical University [grant number CGYP201607]; the Medical Leading Talent Project of Yunnan Province [grant number L201622]; and Yunnan Provincial Clinical Center of Hepato-biliary-pancreatic Diseases [grant number ZX2019-04-04] to L.W; and the Leading Academic and Technical Young and Mid-aged Program of Kunming Medical University [grant number 60118260108] and the Educational Research and Educational Reform Program of Kunming Medical University [grant number 2019-JY-Z-12] to Y. K.