Introduction. Epidemiological studies indicate that nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a common cause of cirrhosis described as ‘cryptogenic’. To address this from a histological perspective and to examine the significance of residual histological findings as an indication of prior NASH, we looked back at biopsies in patients who presented with cirrhosis without sufficient histological features to diagnose NASH but who had prior histologically confirmed non-cirrhotic NASH.

Methods. Seven patients were identified with biopsy pairs showing non-specific (cryptogenic) cirrhosis in the latest specimen and a prior biopsy showing non-cirrhotic NASH. Using an expanded NASH-CRN system scored blindly by light microscopy, we compared the early and late biopsies to each other and to a cohort of 13 patients with cirrhosis due to hepatitis C without co-existing metabolic syndrome.

Results. Macrosteatosis, although uniformly present in the non-cirrhotic NASH specimens, declined in the late stage cirrhotic NASH specimens and was not useful in the distinction of late cirrhotic NASH from cirrhotic viral hepatitis. However, the presence of ballooned cells, Mallory-Denk bodies, and megamitochondria and the absence of apoptotic bodies were significantly different in late stage cirrhotic NASH compared to cirrhosis due to hepatitis C.

Conclusions. Histologically advanced NASH presenting as non-specific or cryptogenic cirrhosis has residual changes which are consistent with prior steatohepatitis but which differ from cirrhosis due to hepatitis C. These results provide histological support for the more established epidemiological associations of NASH with cryptogenic cirrhosis and for criteria used in several proposed classifications of cryptogenic cirrhosis.

A variety of conditions can cause cirrhosis presenting in patients without definitive histological, historical or laboratory findings to indicate the underlying cause. This is usually referred to as nonspecific or cryptogenic cirrhosis and accounts for approximately 8-9% of liver transplantations in the US.1 Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) has been implicated as a common cause of this condition. Serial biopsy studies have shown that about 5-15% of patients with non-cirrhotic NASH will develop cirrhosis within 5-15 years although in most such cases the final biopsy was interpreted either simply as cirrhosis or as consistent with cirrhotic NASH rather than as non-specific or cryptogenic cirrhosis.2

Loss of steatosis as a key indicator of fatty liver disease in late stage NASH was first described by Powell, et al. in 1990.3 We subsequently described a strong epidemiological relationship between NASH and cryptogenic cirrhosis in 1999.4 This association was later confirmed in a number of epidemiological studies5-7 and in reports regarding the post-operative clinical course of patients undergoing liver transplantation for cryptogenic cirrhosis.8,9 Although the epidemiological data has been strong in most reports addressing this problem, very few biopsy pairs have actually been reported wherein a patient with non-specific or cryptogenic cirrhosis (without definitive histological or clinical/laboratory parameters of an underlying disease) has an antecedent biopsy demonstrating non-cirrhotic NASH.

This issue has practical implications related to accurate diagnosis of underlying disease and in proposed classification schemes for cryptogenic cirrhosis.10,11 To address this further, we undertook a systematic look back at prior histology in patients presenting to us with histological cirrhosis identified as non-specific by biopsy but with prior histologically proven non-cirrhotic NASH.

MethodsSeven patients were identified who met the stringent study criteria including a current biopsy diagnosed as non-specific cirrhosis by histological criteria, a prior biopsy and compatible history confirming non-cirrhotic NASH in the past and absence of other liver disease by conventional testing to exclude viral, autoimmune or other liver diseases such as Wilson disease, hemochromatosis or alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. The median time between the biopsy showing non-cirrhotic NASH and that showing non-specific cirrhosis was 6 years. Demographic data of this group are shown in Tables 1 and 2. All but one of these patients met ATP III criteria for metabolic syndrome.12 Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson trichrome stained specimens from the late and early stage specimens were assessed blindly by an experienced pathologist (DK) using an expanded NASH-Clinical Research Network (NASH-CRN) system which included 14 histological features scored semi-quantitatively (Table 3).13

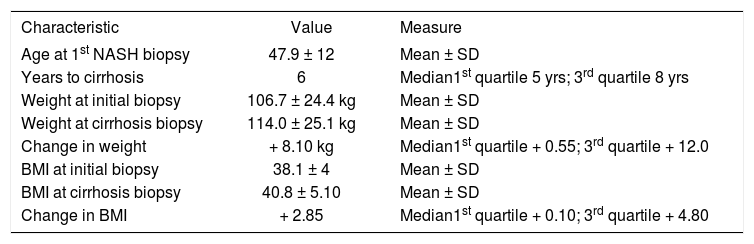

Subjects with non-specific cirrhosis and prior non-cirrhotic NASH.

| Characteristic | Value | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st NASH biopsy | 47.9 ± 12 | Mean ± SD |

| Years to cirrhosis | 6 | Median1st quartile 5 yrs; 3rd quartile 8 yrs |

| Weight at initial biopsy | 106.7 ± 24.4 kg | Mean ± SD |

| Weight at cirrhosis biopsy | 114.0 ± 25.1 kg | Mean ± SD |

| Change in weight | + 8.10 kg | Median1st quartile + 0.55; 3rd quartile + 12.0 |

| BMI at initial biopsy | 38.1 ± 4 | Mean ± SD |

| BMI at cirrhosis biopsy | 40.8 ± 5.10 | Mean ± SD |

| Change in BMI | + 2.85 | Median1st quartile + 0.10; 3rd quartile + 4.80 |

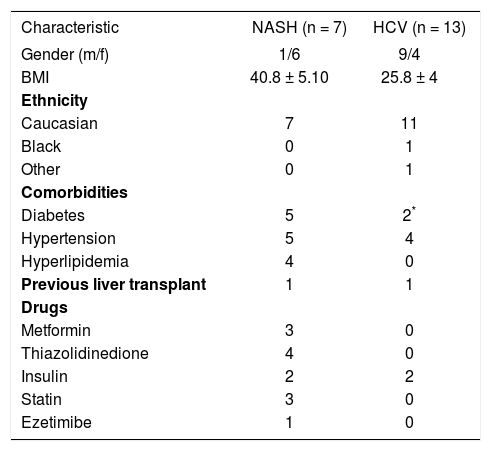

Comparative demographics: Late stage NASH (non-specific cirrhosis) versus hepatitis C-related cirrhosis.

| Characteristic | NASH (n = 7) | HCV (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (m/f) | 1/6 | 9/4 |

| BMI | 40.8 ± 5.10 | 25.8 ± 4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 7 | 11 |

| Black | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 1 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 5 | 2* |

| Hypertension | 5 | 4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 4 | 0 |

| Previous liver transplant | 1 | 1 |

| Drugs | ||

| Metformin | 3 | 0 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 4 | 0 |

| Insulin | 2 | 2 |

| Statin | 3 | 0 |

| Ezetimibe | 1 | 0 |

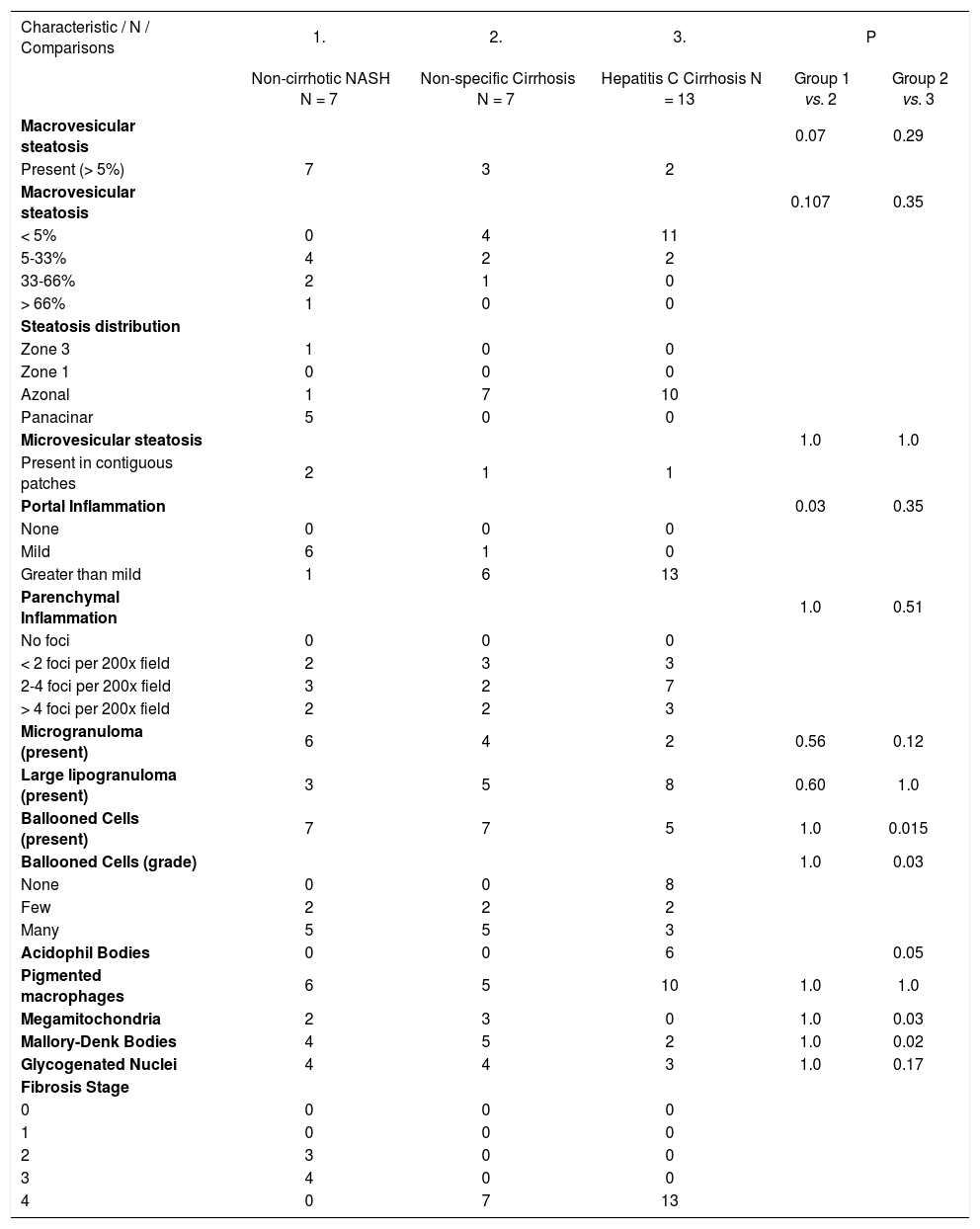

Comparison of NASH-CRN histological features identified in NASH, NASH cirrhosis, and hepatitis C cirrhosis.

| Characteristic / N / Comparisons | 1. | 2. | 3. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-cirrhotic NASH N = 7 | Non-specific Cirrhosis N = 7 | Hepatitis C Cirrhosis N = 13 | Group 1 vs. 2 | Group 2 vs. 3 | |

| Macrovesicular steatosis | 0.07 | 0.29 | |||

| Present (> 5%) | 7 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Macrovesicular steatosis | 0.107 | 0.35 | |||

| < 5% | 0 | 4 | 11 | ||

| 5-33% | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 33-66% | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| > 66% | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Steatosis distribution | |||||

| Zone 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Zone 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Azonal | 1 | 7 | 10 | ||

| Panacinar | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Microvesicular steatosis | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Present in contiguous patches | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Portal Inflammation | 0.03 | 0.35 | |||

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mild | 6 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Greater than mild | 1 | 6 | 13 | ||

| Parenchymal Inflammation | 1.0 | 0.51 | |||

| No foci | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| < 2 foci per 200x field | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||

| 2-4 foci per 200x field | 3 | 2 | 7 | ||

| > 4 foci per 200x field | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Microgranuloma (present) | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0.56 | 0.12 |

| Large lipogranuloma (present) | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0.60 | 1.0 |

| Ballooned Cells (present) | 7 | 7 | 5 | 1.0 | 0.015 |

| Ballooned Cells (grade) | 1.0 | 0.03 | |||

| None | 0 | 0 | 8 | ||

| Few | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Many | 5 | 5 | 3 | ||

| Acidophil Bodies | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.05 | |

| Pigmented macrophages | 6 | 5 | 10 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Megamitochondria | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.03 |

| Mallory-Denk Bodies | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.02 |

| Glycogenated Nuclei | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.17 |

| Fibrosis Stage | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 7 | 13 | ||

In order to ascertain the relative frequency of NASH associated histological parameters in another form of cirrhosis, the specimens from the NASH-nonspecific cirrhosis pairs were compared to a cohort of 13 hepatitis C patients with cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation who were selected based on the absence of metabolic syndrome. Demographic data for these patients is shown in Table 1. These patients tended to be slimmer (mean BMI 25.8 ± 4), and none had hyperlipidemia although four did have a history of hypertension and two of these patients had insulin dependant diabetes. Four had a distant history of moderate or less ethanol use but none within six months and none were felt to have alcohol-related liver disease. Viral genotypes included genotype 1 (n = 8), genotype 4 (n = 2), indeterminate genotype (n = 2) and genotype 3 (n = 1).

One patient in the NASH group and one in the hepatitis C group had previously undergone liver transplantation, one for cryptogenic cirrhosis in the former group and one for hepatitis C related cirrhosis in the latter group. Both of these patients were included because they met our inclusion criteria and it was felt that the inclusion of these patients broadened the findings.

The Fisher’s exact test and signed rank test performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) were used to compare the categorically scored histological features in the non-cirrhotic NASH patients, their paired biopsy showing non-specific cirrhosis and the cirrhotic hepatitis C patients. The protocol for this study was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board.

ResultsAmong the patients with histological NASH, all were obese at the time of the first biopsy with a mean BMI of 38.1 (range 32.2-42.5) and a mean age of 47.9 years (range 29 to 58 yrs) at the time of diagnosis (Table 1). These patients progressed from NASH with fibrosis stage 2 (3 subjects) or 3 (4 subjects) to the appearance of non-specific cirrhosis over a median of 6 years (range 3 to 11 years). All but one of the patients gained weight in this interval with a median change in weight and BMI of +8.10 kg and +2.85 respectively without evidence of ascites. Compared to the hepatitis C group (Table 2), there was a significantly higher proportion of diabetes (p = 0.02) and hyperlipidemia (p = 0.007) in the NASH group. Consistent with these conditions, the NASH patients were more frequently treated with metformin (n = 3), thiazolidinediones (n = 4), and statin-type medications (n = 3), p < 0.05 for each agent.

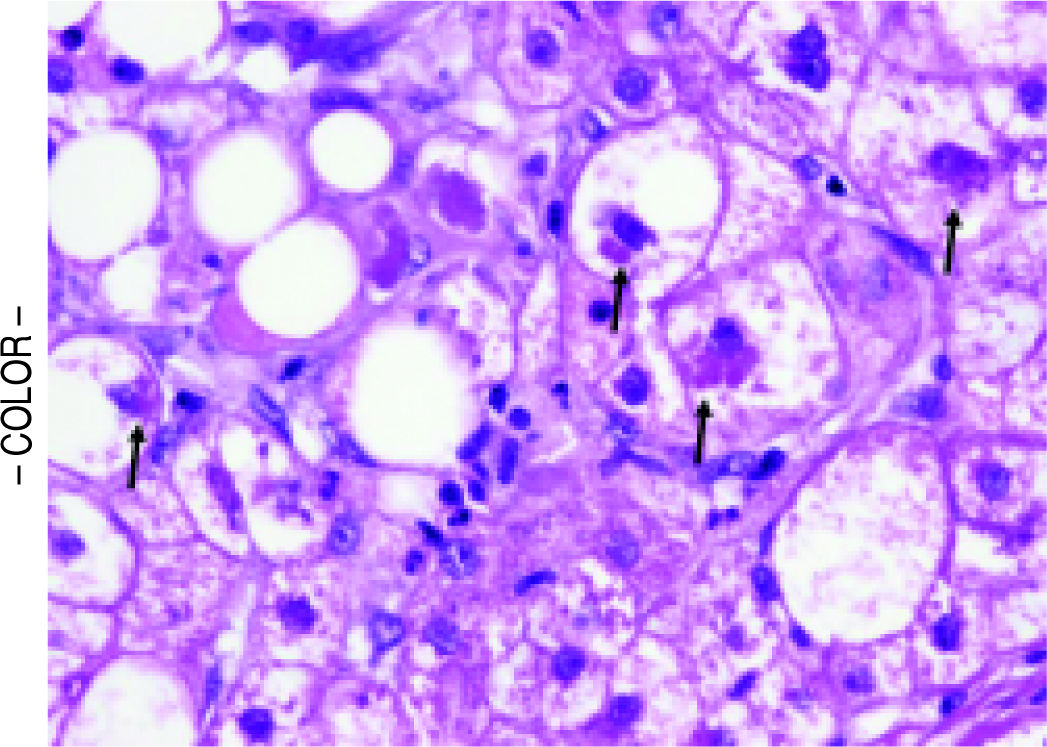

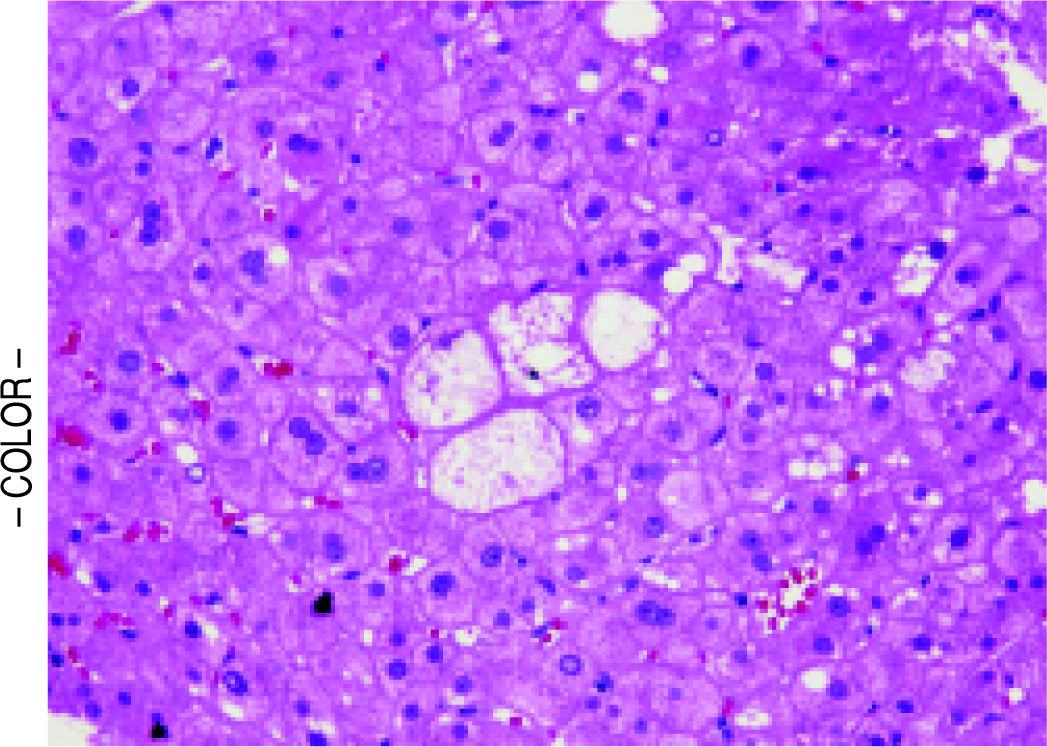

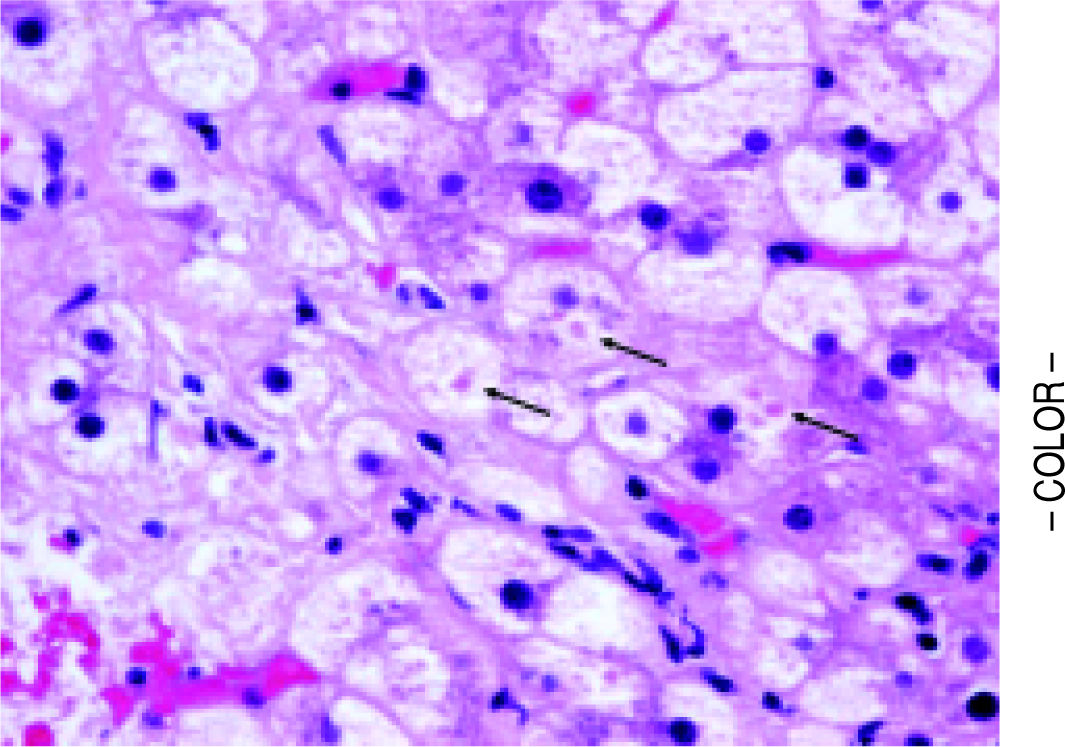

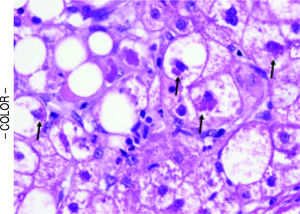

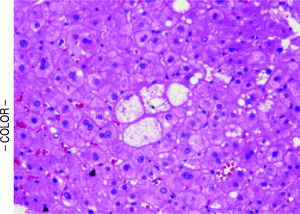

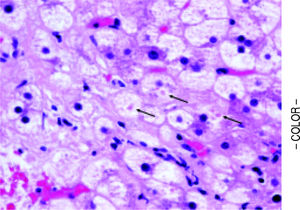

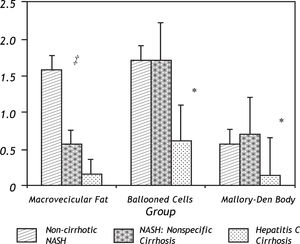

Table 3 shows the comparisons of histological features between the prior NASH biopsy and the subsequent non-specific cirrhosis specimens in the NASH group. There was a statistical trend towards complete loss of macrosteatosis. When classified as present or absent, all subjects had macrosteatosis in the prior non-cirrhotic NASH specimen but 4 out of 7 subjects had complete loss of macrosteatosis in the cirrhosis biopsy specimen (p = 0.07). However, there was no significant difference in the presence of ballooning (Figures 1 and 2) evident in 5 out of 7 patients at both the NASH stage and the non-specific cirrhosis stage or in the presence of microsteatosis in the early versus late stage samples. Portal inflammation increased as subjects progressed from NASH to cirrhosis (p = 0.03) whereas parenchymal inflammation was unchanged. Mallory-Denk bodies (Figures 1 and 2), megamitochondria (Figure 3), glycogenated nuclei, microgranulomas, lipogranulomas, and pigmented macrophages were noted equally in both the non-cirrhotic NASH and the late stage cirrhosis specimens. Acidophil (apoptotic) bodies were notably absent in both stages.

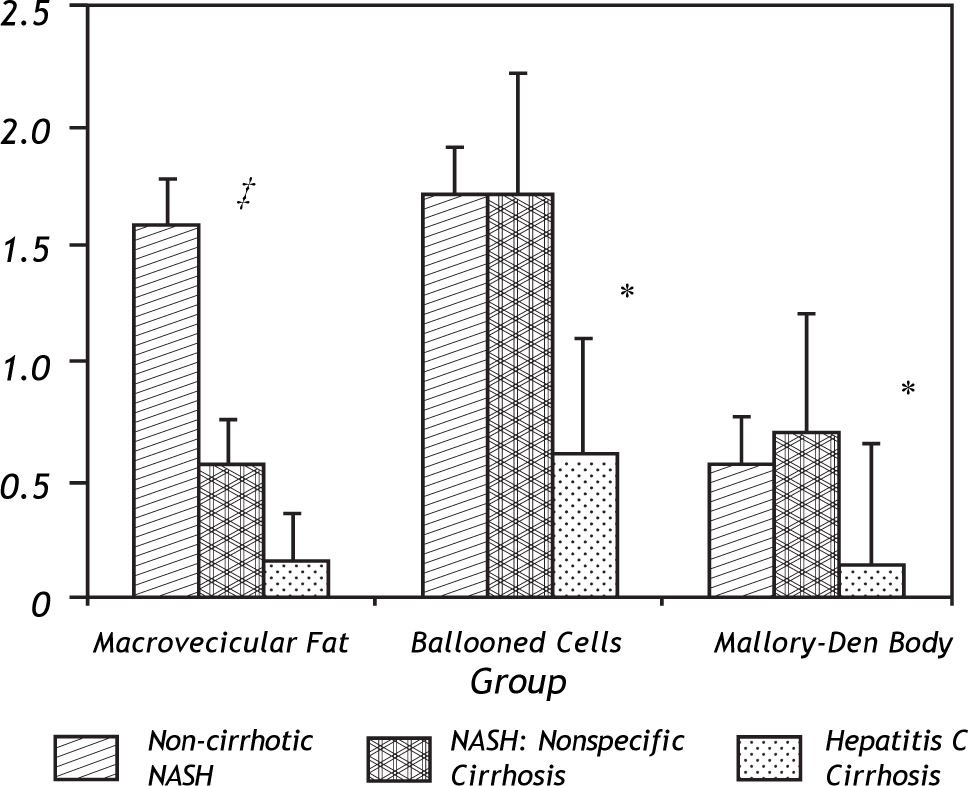

Results comparing the histological features of the NASH group to those from hepatitis C cirrhosis are shown in Table 3 and Figure 4. In terms of macrosteatosis, late stage NASH resembled cirrhosis due to viral HCV because macrosteatosis was minimal in both cirrhotic groups including the single patient (grade 1 steatosis) with genotype 3 hepatitis C. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in the presence (p = 0.29) or the grade of macrosteatosis (p = 0.35) between the NASH-related ‘nonspecific’ cirrhosis group and the hepatitis C cirrhosis group. However, the presence and the grade of ballooned cells (p = 0.015, p = 0.03 respectively), the presence of megamitochondria (p = 0.03) and the presence of Mallory-Denk bodies (p = 0.02) were significantly greater in the NASH-related cryptogenic cirrhosis group compared to hepatitis C related cirrhosis. There was also a strong trend towards significance in the absence of acidophil bodies in the NASH group. Acidophil bodies were identified in 6 out of 13 hepatitis C cirrhosis specimens but were absent in both the early and the late stage NASH group (p = 0.05).

Differences in macrosteatosis, cellular ballooning and Mallory-Denk body histological scores between the three groups including the early non-cirrhotic NASH biopsy, the later paired non-specific cirrhosis specimen and the control group of hepatitis C patients who lacked metabolic syndrome.‡ Indicates a statistical trend (p = 0.07) in the loss of macrovesicular fat in the early (non-cirrhotic NASH) versus late (non-specific cirrhosis) NASH patients. * Indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between the early or late NASH samples versus the hepatitis C group.

Epidemiologic data support that progression of NASH is one of the more common causes of cirrhosis characterized histologically as non-specific and clinically as cryptogenic. Compared to the epidemiological literature, the histological literature is relatively less established in this regard. Although progression of NASH to cirrhosis is very well known from serial biopsy studies, we are aware of only 21 histologically confirmed cases in published papers which document progression of histological NASH to a stage of nonspecific (without definitive features of NASH) cirrhosis by biopsy.3,14-21 In the present study, we have looked back at prior histological specimens in patients presenting to us with cirrhosis which histologically was diagnosed as non-specific and compared these specimens to the prior NASH samples and to cirrhosis related to hepatitis C.

Strict entry criteria limited the focus of this study to these unique patients presenting with histologically non-specific cirrhosis who also had a prior biopsy (usually from an outside institution) consistent with non-cirrhotic NASH. Blinded assessment of these biopsies and comparison of these pairs with cirrhosis due to hepatitis C in patients without co-existing metabolic syndrome revealed that late stage NASH possesses some distinctive features consistent with antecedent NASH including ballooned hepatocytes, Mallory-Denk bodies, and megamitochondria (Figures 1-3). These results support previously proposed classification schemes for cryptogenic cirrhosis.9-11

The most prominent histological feature which changed in early versus late stage NASH was the loss of macrosteatosis-usually considered an essential but not sufficient indicator of NASH. Indeed, there was no significant difference in macrosteatosis between the late stage NASH specimens and the late stage hepatitis C specimens from patients without metabolic syndrome-both of the cirrhotic groups had relatively low macrosteatosis compared to the NASH samples (Figure 4). Counted as present or absent, 4 of 7 NASH patients completely lost evidence of this feature in the late-stage, non-specific cirrhosis biopsy.

Although unresolved, several explanations for loss of steatosis have been proposed including altered hepatic blood flow resulting in altered insulin exposure and abnormal glucose and lipoprotein delivery due to sinusoidal injury.22-24 Another less established explanation involves repopulation of the native liver with one derived from disease-resistant stem cells (oval cells) leading to fundamental changes in hepatic fat metabolism and diminished fat storing capacity. In support of this mechanism, such cells constitute the majority of cells in regenerating cirrhotic nodules in NASH-cirrhosis.25 Cirrhosis-related malnutrition is another possibility. However, weight gain was seen in the NASH patients in the interval between the first and second biopsy. Because none of these patients had over complications of portal hypertension such as ascites, the weight gain was unlikely to be due to simple fluid retention. This suggests that diminished macrosteatosis in advancing NASH was not simply due to systemic cirrhosis-related malnutrition.

Acidophil bodies were distinctly less evident in both early and late stage NASH compared to hepatitis C cirrhosis specimens. This was somewhat paradoxical given the prominent role of apoptosis pathway activation in NASH pathogenesis. It suggests that cell death may proceed more by necrosis or necroapoptosis but the issue remains to be resolved. We also noted significantly increased inflammation in the residual portal areas as NASH progressed to non-specific cirrhosis. This is in keeping with more recent reports on portal involvement in NASH but contrasts to prior studies on this issue.3,16,26,27 The reason for this discrepancy is unclear.

There are several inherent limitations in this work. As a ‘look back’ study, it is retrospective by design as we worked back from patients presenting with non-specific cirrhosis defined histologically. Strict entry criteria also required that such patients have an antecedent biopsy showing non-cirrhotic NASH thus introducing a specific bias but which actually constituted an aim of the study – to compare these well-defined biopsy pairs. However, this also limited case ascertainment because most of the antecedent biopsies were performed at outside institutions as long ago as 11 years thus limiting the size of the study to those in whom both specimens could be obtained for blinded review.

Another limitation of our analysis of this data is the inherently categorical nature of the NASH-CRN scoring system characteristic of all such scoring systems. Because the primary aim of this study was to assess residual features of NASH in non-specific cirrhosis in patients with proven prior NASH, we elected to utilize a system designed specifically for NASH rather than other systems such as Ishak often applied to viral hepatitis. Also, the inclusion of two patients (one in the NASH group and one in the hepatitis C group) who had prior liver transplantations may have added a degree of heterogeneity. However, both subjects met strict entry criteria and were included as it was felt to broaden the study and demonstrated the occurrence of post-transplant NASH with progression to non-specific cirrhosis.

In conclusion, our results provide further histological evidence to support the progression of NASH to a late stage in which there is loss of diagnostic features of NASH leading to a histological diagnosis of ‘non-specific cirrhosis’ and a clinical diagnosis of ‘cryptogenic cirrhosis’. These results confirm that residual histological features of NASH remain even in these advanced cases and distinguish this form of cryptogenic cirrhosis from cirrhosis caused by advanced hepatitis C. In particular, hepatocyte ballooning, Mallory-Denk body formation and megamitochondria and a paucity of acidophil bodies may aid in the interpretation of these cases. Further studies are warranted to understand the mechanisms involved with loss of steatosis as the disease progresses and to develop other histological markers of prior lipid-induced oxidative injury.

Abbreviations- •

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- •

NASH-CRN: NASH-Clinical Research Network

- •

NIDDK: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- •

BMI: Body mass index