When portal venous gas (PVG) is found, it is usually considered an ominous sign. It is now more frequently found because of the improvement in imaging studies, mainly through computed tomography (CT). It was first related primarily to mesenteric ischemia. However, it is now identified in other conditions and the prognosis is not related to the presence in itself of PVG, but to the nature and severity of the underlying condition or disease that causes it. Next, we report three patients with portal venous gas that were seen at our surgical department. All the patients presented acute abdominal pain and during their diagnostic studies, portal venous gas was identified. Intestinal ischemia was diagnosed in two of them, who underwent an exploratory laparotomy, one of them died within 24 hours. In the other patient, the pain subsided and was treated medically and the recovery was uneventful. In conclusion: the most important factor related to portal venous gas is the disease that caused it. The most common cause of PVG is mesenteric ischemia, so every effort should be made to rule it out, as the prognosis is related to an early diagnosis and almost all patients require surgery. Other causes had been reported and conservative treatment could be used in selected cases.

PVG: portal venous gas

CT: Computed Tomography

IntroductionThe presence of gas in the intra-hepatic or extra-hepatic portal vein is a signal that has been usually associated with a lethal outcome. It was first described in children in 1955 and 5 years later in adult patients.1,2 Nowadays this disease is being frequently identified thanks to the improvement of imaging studies, mainly the increased utilization of CT.2 It was formerly associated primarily, to intestinal ischemia but its presence has been reported in other settings, many of which do not require surgery for their solution.3 In this paper we report three patients with portal venous gas seen in our surgical department and analyze the factors associated to it.

Case reportCase 1A 94-year-old female with history of hypertensive cardiopathy was seen in the emergency room. Her main complaint was abdominal pain lasting two days which worsened in the previous 12 hours to her arrival. It initiated in the lower abdomen then became generalized short after adding nausea and vomiting. During physical examination her vital signs were normal and despite having abdominal pain there were no signs of abdominal irritation. Blood analysis showed a white blood cell count of 12,500 per μl with bandemia. Arterial blood gas analysis showed an uncompensated metabolic acidosis. The abdominal computed scan showed gas in the intra-hepatic and extra-hepatic portal vein. Due to her age and condition, her relatives did not accepted surgery and she was admitted for medical treatment (antibiotics and bowel rest). The evolution was uneventful and she was discharged one week later without complications. She was doing well six months later.

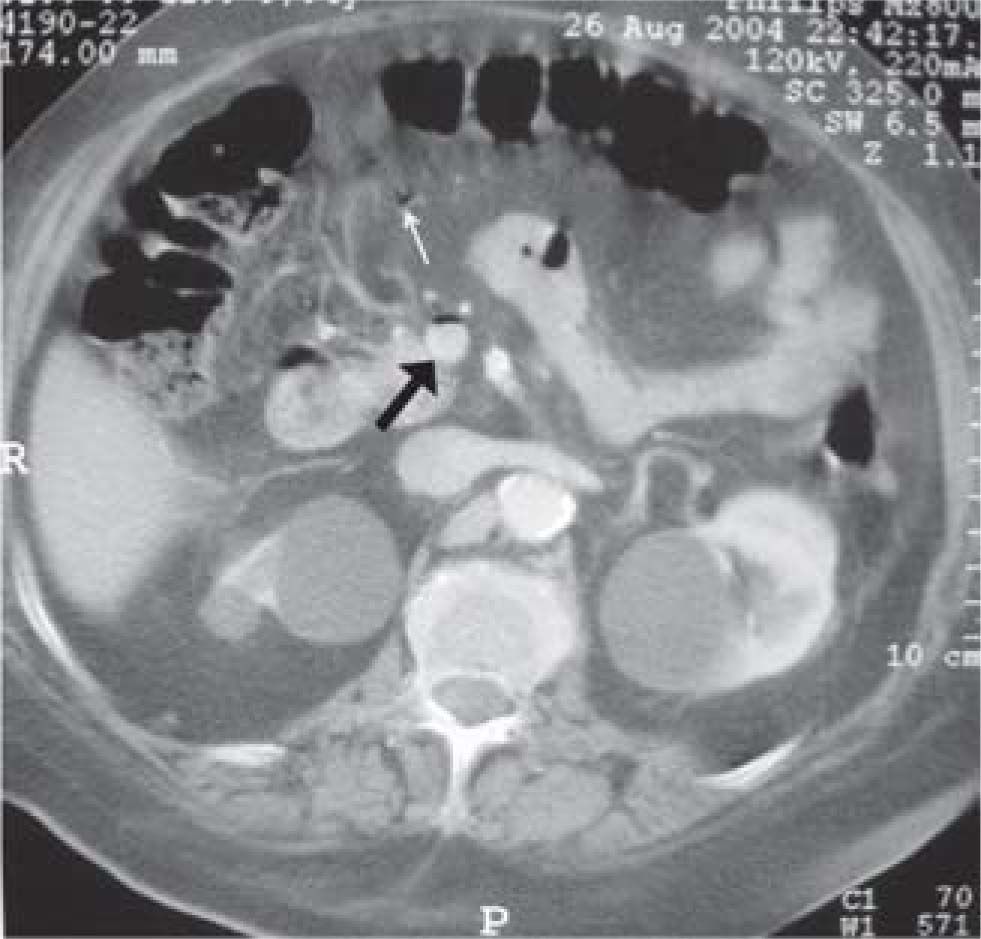

Case 2A 62-year-old female with history of ischemic cardiopathy, diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure in hemodialysis treatment, complained of generalized abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea and vomiting which had lasted for one day. During physical examination she was afebrile, had abdominal guarding, tenderness and absence of intestinal sounds, she also had rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed white blood cell count of 16,300 per μl with left shift, severe anemia and hyperglycemia. The CT scan revealed gas in the intra-hepatic and extra-hepatic portal vein along with thickening of the small bowel wall and pneumatosis intestinalis. Based in these findings, diagnosis of intestinal ischemia with necrosis was made and she underwent an intestinal resection of three feet of small bowel with a lateral-to-lateral anastomosis. She died 24 hours later due to metabolic complications.

Case 3A 42-year-old male with history of Hepatitis B Virus (unknown cause of infection), systemic hypertension, and chronic renal failure, came to our service complaining of generalized abdominal pain, abdominal distention, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting in the last 24 hours. Examinations revealed severe tenderness, abdominal guarding, absence of intestinal sounds and rebound tenderness. His initial laboratory disclosed white blood cell count of 13,500 per μl, anemia and hydro-electrolytic disorder. A CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated pneumatosis intestinalis, and gas in the intra-hepatic and extra-hepatic portal vein. We made the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia and was scheduled for exploratory abdominal surgery. At operation, patch intestinal ischemia was found all over the small intestine, no procedure was realized and the abdomen was closed with the intention of getting better health conditions. Despite medical treatment, he required dopamine infusion because of persistent hypotension, the abdominal pain continued and a “second look” surgery was scheduled 48 hours later, in which we found a much better perfusion at small intestine. Postoperatively the patient’s abdominal pain resolved with no complains or complications, the dopamine infusion was cut-over and the patient was discharged one week later, with no symptoms in his 5-month follow-up.

DiscussionThe presence of gas in the intra-hepatic portal system was first described in children with necrotizing entero-colitis by Wolfe and Evans in 1955.1,2 Five years later, Susman and Senturia reported it in adult patients.1 Historically the most common cause of PVG was bowel ischemia, which was associated to a 75 per cent mortality rate.3 Since many cases are related to severe intestinal ischemia its presence is considered an ominous sign.1,4-6

The presence of gas in the portal system has three main theories, 1) passage of gas from the intestinal lumen through a defect of the intestinal mucosa or, a retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal abscess, with circulation to the liver, 2) the presence of gas-forming-bacteria in the portal system which then circulate to the peripheral circulation and 3) increase in luminal gas pressure as seen in bowel obstruction or gastrointestinal endoscopies. These theories had been confirmed in animal models and similar changes had been found that have supported them in humans.2,7 The clinical presentation can be divided in three categories based on PVG pathophysiology. These three categories are bowel obstruction, ischemic pathology, and infectious processes.8

Diagnosis can be made with imaging studies such as plain abdominal films, ultrasound and abdominal CT scans, with the last being the most sensitive of all. Plain abdominal films show the presence of radiolucid branches in the hepatic area, but a large amount of gas must be present to be identified, this could be improved if the x-ray is taken with the patient lying on his or her left side.1,5,9 Ultrasound reveals the presence of small hyperechogenic images with variable acoustic shadows or poorly defined hyperechogenic patches in the hepatic parenchyma.2,9,10

Nowadays, the improvement and the increased utilization of the CT scans, the most sensitive test for the diagnosis,2,9,11 allows visualization of tubular areas of diminished attenuation in the liver, predominantly in the left lobe, because it has a more ventral position.1,11 Differentiation from pneumobilia has to be made. The gas in the portal system extends within 2 cm of the hepatic capsule due to the centrifuge circulation of the blood, and when the gas is in the biliary system it is primarily located centrally, due to the centripetal circulation of bile.1,10 The amount of gas seen in the CT is not related to the severity of the underlying disease. Another advantage of this test is that in patients with a suspicion of intestinal ischemia, CT provides more information compared to the other diagnostic exams that are usually made to make the diagnosis.2,5,6,9,12 Because of the relevance of PVG, the radiologist should look for other signs of a probable illness or pathology that causes it. This may help the surgeon to decide surgical or medical management, when the clinical findings aren’t clearly enough.8 In our patients the diagnosis was made by CT scan, all of them had gas in the intra-hepatic portal vein and two of them had signs of intestinal ischemia (pneumatosis intestinalis) which was confirmed during surgery (Figures 1and2).

As shown in Table I, the treatment, and also the prognosis, depends on the cause of the gas.1,7 Most cases of hepatic portal venous gas are related to acute intestinal ischemia with or without pneumatosis intestinalis.1,2,13-15 Other causes of hepatic portal venous gas are retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal abscess, inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal distention, gastric ulcer, pancreatitis, endoscopy, intra-abdominal tumors, cholangitis, fulminant hepatitis or trauma, among others.1,2,5,7,14-16

Etiology and treatment of patients with portal venous gas (with patients from references 1,3,4,6-10,12-19,22 and the ones herein reported). (GI: gastrointestinal bleeding).

| Etiology | Total (n = 131) | Patients | Deaths | Mortality % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestinal Ischemia | 68 (52%) | 68 | 44 | 65 |

| Surgical treatment | 52 | 28 | 54 | |

| Medical treatment | 16 | 16 | 100 | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 13 (10%) | 13 | 2 | 15 |

| Surgical treatment | 10 | 1 | 10 | |

| Medical treatment | 3 | 1 | 33 | |

| Undetermined | 13 (10%) | 13 | 4 | 31 |

| Surgical treatment | 5 | 2 | 40 | |

| Medical treatment | 8 | 2 | 25 | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 6 (5%) | 6 | 2 | 33 |

| Surgical treatment | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 6 | 2 | 33 | |

| Inflammatory or infectious diseases | 7 (5%) | 7 | 1 | 14 |

| Surgical treatment | 3 | 1 | 33 | |

| Medical treatment | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 5 (4%) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Complicated diverticular disease | 4 (3%) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Perforated ulcer | 3 (2%) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cancer | 3 (2%) | 3 | 1 | 33 |

| Surgical treatment | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 1 | 1 | 100 | |

| GI Bleeding | 3 (2%) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vascular pathologies (non Ischemic) | 3 (2%) | 3 | 2 | 66 |

| Surgical treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 2 | 2 | 100 | |

| Biliary sepsis | 3 (2%) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgical treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 131 (100%) | 131 | 57 | 44 |

| Surgical treatment | 81 | 32 | 40 | |

| Medical treatment | 50 | 24 | 48 | |

| Total (without intestinal ischemia) | 63 (48%) | 63 | 12 | 19 |

| Surgical treatment | 29 | 4 | 14 | |

| Medical treatment | 34 | 8 | 24 |

A thorough evaluation of the patients is essential.5,13 CT scans can not replace proper history-taking examination, identifying cases of PVG that do not require surgical treatment as many cases could be managed medically.17 It is of utmost importance that most, if not all, the patients with abdominal symptoms and findings compatible with intestinal ischemia usually have it, and require surgery; an early diagnosis is vital because a delay increases significantly the mortality rate.5,4,17 Conservative treatment has been reported, but with a very high mortality rate, although some of these patients were to ill to survive surgery. The CT scan findings that leads to the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia are: thickening of the intestinal wall, ascites, alterations to the mesenteric vessels and pneumatosis intestinalis.6,12,13 The occurrence of this last disease with PVG has very poor prognosis, which is determined by the extent of ischemic bowel, as seen in our patients, the one who had only ischemic bowel without infarction survived, while the other with pneumatosis and necrosis died. If another cause is suspected as the one related to this finding, such as post procedural, inflammatory bowel disease or pancreatitis; then a case-to-case decision should be made.18 The treatment could be conservative and in many cases this would be enough. It is important to identify the cause to avoid unnecessary laparotomies.18

The prognosis is related to the cause of the gas. Identification of gas in the plain abdominal films is associated with a poor prognosis, but the amount of gas is not. It is an ominous sign because most patients have intestinal ischemia.1 Also shown in Table 1, the prognosis of PVG is radically different if it is related to mesenteric ischemia (mortality ranging from 54 -100%) when compared to all the other causes. (mortality ranging from 14-24%).1,6,8,13,14 This is decreasing in part to the improvement of the imaging tests that allows an earlier diagnosis. Patients with benign surgical illness, e.g., small bowel obstruction with or without limited bowel necrosis, or large bowel obstruction, once treated, it seems to have a very good prognosis, and the follow-up is not different from the expected course of the same population of patients without PVG.8 PVG is in and of itself not a harbinger of mortality but can be interpreted as a sign of a need for aggressive support and serial evaluation in patient’s care. Close observation may be appropriate in stable patients with PVG without other specific findings for abdominal catastrophes.3

Several algorithms7,18-20 had been proposed as guides for management of PVG. As in more than half the patients this finding is related to mesenteric ischemia, every effort should be done to determine if the patient has this pathology, and if this is the case, then the most adequate treatment is surgery. In presence of a patient with abdominal signs and with an undetermined pathology, probably the best approach is surgery, and in cases in which the origin of the gas is iatrogenic (endoscopy, imaging studies) or is a finding in a patient with no abdominal pain or signs, then a conservative approach could be the best one (Figure 3).

ConclusionsThe most important factor related to portal venous gas is the disease that caused it. Many patients have mesenteric ischemia but the proportion of patients with other causes is increasing, and have better prognosis. Close observation may be appropriate in stable patients with PVG without other specific findings for abdominal catastrophes. If the cause of the PVG is due to surgical illness, the surgery should be done as soon as the diagnosis is made, because the prognosis and follow-up is the same as patients without PVG.