Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a slowly progressive autoimmune liver disease that may ultimately result in liver failure and premature death. Predicting outcome is of key importance in clinical management and an essential requirement for patients counselling and timing of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. The following factors are associated with progressive disease and worse outcome: young age at diagnosis, male gender, histological presence of cirrhosis, accelerated marked ductopenia in relation to the amount of fibrosis, high serum bilirubin, low serum albumin levels, high serum alkaline phosphatase levels, esophageal varices, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and lack of biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). The prognostic significance of symptoms at diagnosis is uncertain. UDCA therapy and liver transplantation have a significant beneficial effect on the outcome of the disease. The Mayo risk score in PBC can be used for estimating individual prognosis. The Newcastle Varices in PBC Score may be a useful clinical tool to predict the risk for development of esophageal varices. Male gender, cirrhosis and non-response to UDCA therapy in particular, are risk factors for development of HCC.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is an autoimmune liver disease characterized by chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis, typically affecting middle-aged women.1,2 The disease is relatively rare with reported incidence rates varying from 0.33 to 5.8 per 100,000 persons/year and prevalence rates ranging from 1.91 to 40.2 per 100,000 persons.3 Fatigue and pruritus are the most prevalent symptoms and have a major impact on quality of life, particularly in young patients.4,5 The only accepted medical treatment is ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), while liver transplantation is a lifesaving option in persons who have progressed to end-stage disease.6,7

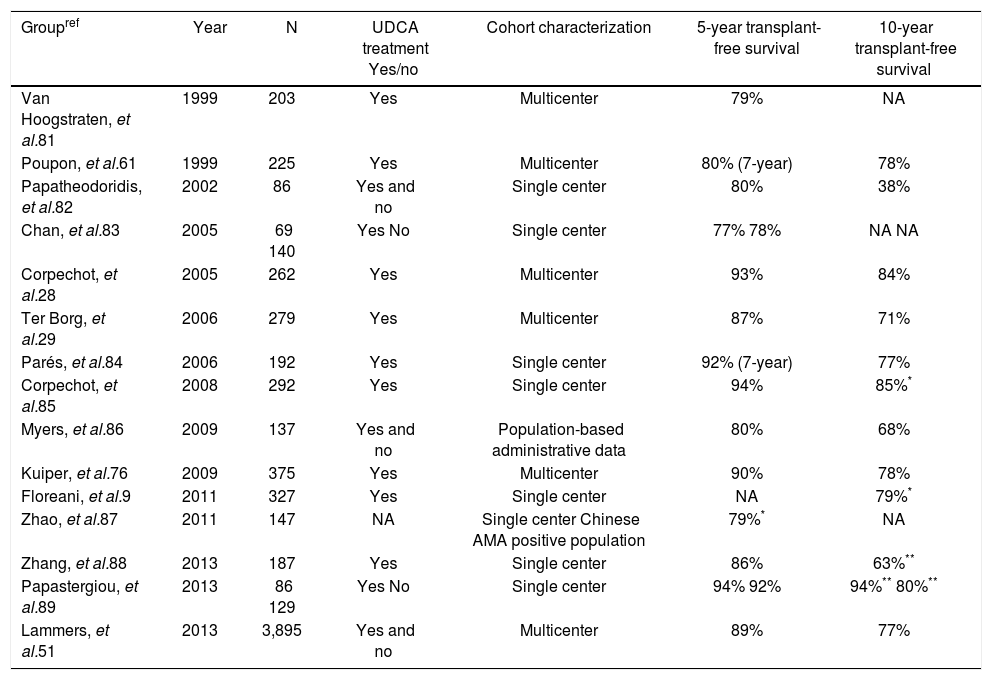

PrognosisPBC usually has a slowly progressive course and contrary to the name, generally considered a classical misnomer, cirrhosis is only manifest in the late stages of the disease. The life expectancy of affected patients is worse compared with the general population, but on an individual basis the course of the disease and the prognosis vary greatly. Currently, patients are more likely to be asymptomatic and diagnosed at earlier stages of the disease.8–10Table 1 summarizes studies published in the last fifteen years reporting 5- and 10- year liver transplant-free survival rates based on Kaplan Meier estimates. The reported differences in outcome are probably attributable to differences in study populations and variability with respect to duration and dose of treatment with UDCA.

Reported prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis.

| Groupref | Year | N | UDCA treatment Yes/no | Cohort characterization | 5-year transplant-free survival | 10-year transplant-free survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Hoogstraten, et al.81 | 1999 | 203 | Yes | Multicenter | 79% | NA |

| Poupon, et al.61 | 1999 | 225 | Yes | Multicenter | 80% (7-year) | 78% |

| Papatheodoridis, et al.82 | 2002 | 86 | Yes and no | Single center | 80% | 38% |

| Chan, et al.83 | 2005 | 69 140 | Yes No | Single center | 77% 78% | NA NA |

| Corpechot, et al.28 | 2005 | 262 | Yes | Multicenter | 93% | 84% |

| Ter Borg, et al.29 | 2006 | 279 | Yes | Multicenter | 87% | 71% |

| Parés, et al.84 | 2006 | 192 | Yes | Single center | 92% (7-year) | 77% |

| Corpechot, et al.85 | 2008 | 292 | Yes | Single center | 94% | 85%* |

| Myers, et al.86 | 2009 | 137 | Yes and no | Population-based administrative data | 80% | 68% |

| Kuiper, et al.76 | 2009 | 375 | Yes | Multicenter | 90% | 78% |

| Floreani, et al.9 | 2011 | 327 | Yes | Single center | NA | 79%* |

| Zhao, et al.87 | 2011 | 147 | NA | Single center Chinese AMA positive population | 79%* | NA |

| Zhang, et al.88 | 2013 | 187 | Yes | Single center | 86% | 63%** |

| Papastergiou, et al.89 | 2013 | 86 129 | Yes No | Single center | 94% 92% | 94%** 80%** |

| Lammers, et al.51 | 2013 | 3,895 | Yes and no | Multicenter | 89% | 77% |

The ability to reliably predict outcome in patients with PBC is critically important in clinical management and an essential requirement for patient counselling and timing of diagnostic procedures and therapeutic interventions. The aim of this review is to examine established prognostic factors and available tools for estimating prognosis in individuals with PBC, including predictive scoring models for two of the most serious clinical complications, namely esophageal variceal bleeding and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Factors Determining PrognosisHistological stageSeverity of disease in PBC is based on the Scheuer14 and Ludwig1 histologic scoring systems, both recognizing 4 stages. Early histological stages are associated with favourable prognosis. The last phase, or cirrhotic phase, is irreversible and classically only this stage is associated with an increased risk of liver decompensation and development of HCC.6,11 Thus, liver histology is a strong prognostic factor.

A particular variant form of PBC, the premature ductopenic variant, is characterized by rapid, excessive bile duct loss in relation to the amount of fibrosis. In individuals with this subtype, severe cholestasis with progressive jaundice and marked hypercholesterolemia may require liver transplantation well before the development of cirrhosis.12

Histological progression of PBC was assessed in patients originally included in a clinical trial of D-penicillamine.13 Since this agent does not delay histological progression,14 this study is considered as representative of histological progression in treatment-naïve PBC patients. Approximately 80% of patients had histological progression of at least one stage during a median follow-up of 3 years, and 31% with stage I disease progressed to cirrhosis within 4 years. Another study followed-up 183 patients treated with UDCA and reported a 4% incidence of cirrhosis at 5 years in patients with stage I disease,15 suggesting that UDCA delays histological progression.

Several other histologic features have been described as important prognostic parameters of worse outcome in PBC, such as central and periportal cholestasis,11,16 periportal cell necrosis and piecemeal necrosis,15,16 interface hepatitis,15 and ductopenia.17

Many of these histological features are not systematically included in the Ludwig and Scheuer histological scoring systems; in fact, an expert panel on PBC, working under the auspices of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), agreed that histology should neither be included in prognostic scoring models nor used as a primary endpoint in clinical trials.18 A recently proposed histologic scoring system taking into account several of the histological features discussed awaits further validation.19

Efficacy of treatmentTreatment options in PBC are limited. Liver transplantation is the only curative treatment for PBC with excellent survival rates,20 but is an option only for patients with end-stage liver disease. UDCA is the only approved treatment for PBC,6,7 although several metaanalyses have failed to show a beneficial effect of UDCA in PBC.21–23 However, only a few of the included studies lasted longer than 24 months, a very short period to demonstrate effects on transplant-free survival, and most studies were clearly underpowered. In contrast, a pooled analysis of individual patient data from the 3 largest placebo-controlled double-blind studies which included longer follow-up data from one center, showed an improvement in survival with UDCA after four years of treatment.24 Another meta-analysis showed that the use of UDCA in studies that incorporated placebo control, long-term follow-up (more than 2 years) or larger numbers of patients (more than 100 patients) were associated with both improved serum liver biochemical tests and reduced incidence of liver transplantation or death.25

Several studies extending the follow-up of earlier published randomized, placebo-controlled UDCA trials showed that UDCA not only improves some histological features, but can delay histological progression. Two separate studies from the U.S. and France demonstrated a delay in histological progression after a minimum of four years of UDCA treatment.17,26 A combined analysis, which also used data from a Canadian and Spanish trial, showed that histologic progression was delayed after 2 years treatment, but that UDCA treatment was not associated with regression of fibrosis.27

Several studies have shown that UDCA-treated patients with early stage disease have survival rates comparable with a standardized general populaion.28,29 For UDCA-treated patients with advanced disease survival was diminished compared with an age- and sex-matched controlled population.

In summary, there is strong evidence to support the use of UDCA to delay the progression of PBC and currently it remains the only licensed medical therapy.

Gender and age at time of diagnosisData on the prognostic significance of factors such as gender or age are scare. A recent landmark study from the UK PBC consortium clearly showed the impact of important disease subgroups in a study cohort including 2,353 PBC patients.4 Importantly, male patients were less likely to respond to UDCA treatment and were at higher risk of worse outcome. Another important finding was an inverse relationship between age and likelihood to respond to UDCA. Thus, gender and age appear important in predicting prognosis in PBC.

Presence of symptoms at time of diagnosisRisk stratification according to the presence of symptoms at time of diagnosis has been the subject of many studies over the past decades.16,30–35 Of note, most studies did not use validated symptom assessment measures, which is essential for assessing the impact of subjective parameters, such as fatigue or pruritus. Therefore interpretation of such studies may be difficult.

Most studies have reported that asymptomatic patients have earlier histologic stage of disease compared with symptomatic patients, in addition to better liver enzyme profiles and lower bilirubin and higher albumin levels.36 Several studies showed that a substantial proportion of asymptomatic patients will develop symptoms over time.31,34,36–38 The vast majority (95%) of asymptomatic patients followed for up to 20 years will become symptomatic.8 Once symptoms appear, survival of initially asymptomatic patients is comparable with survival of patients who initially presented with symptoms.33,36 Therefore asymptomatic PBC patients rather appear to represent an earlier stage of the disease than a separate clinical entity.

Serological prognostic factorsAntimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) are highly specific for PBC and a cornerstone for establishment of the diagnosis. Up to 95% of PBC patients have positive AMA titers,39 and patients having positive AMA in combination with normal serum liver biochemical tests and without symptoms are likely to develop PBC over time.37 However, neither AMA status nor AMA titer has been shown to be correlated with prognosis.40,41 AMA subtypes were found to be associated with a progressive course in some studies,42 but this was not confirmed by others.43,44

Approximately half of PBC patients also have anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) detectable in serum. In particular, ANA against anti-Sp100 and antigp210 antigens are highly specific for PBC and therefore useful to establish the diagnosis of PBC in AMA-negative patients.45 It has been suggested that patients with initially positive anti-gp210 have more active disease and are more likely to develop liver failure.46,47

Biochemical prognostic factorsFrom a diagnostic point of view increased serum alkaline phosphatase values (ALP) with or without increased gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (γ-GT) are important, and both are considered as early markers of cholestasis in contrast to elevated serum total bilirubin values, which are clearly suggestive of more advanced disease.48

It has been known for several decades that serum bilirubin is one of the most powerful predictors of prognosis in PBC and this variable has been incorporated in most scoring and prediction models. A classical study demonstrated a two-phase pattern of bilirubin during the course of the disease;49 a first phase in which serum bilirubin remains stable for many years and a second phase of rapidly increasing values, the so called ‘acceleration phase’. Repeated measurements of serum bilirubin > 2.0mg/dL was a sign of late stage disease and preceded death within a few years.49 A French study showed that persistent abnormal bilirubin levels were predictive for extensive fibrosis, with a positive predictive value of 90%.15 In patients in whom serum bilirubin normalizes upon treatment with UDCA, transplant-free survival was found to be comparable with that in placebo-treated patients with initial normal serum bilirubin levels.50 The same applied to survival of patients without normalization of bilirubin and placebo-using patients with abnormal bilirubin values at baseline. In other words, serum bilirubin values retain prognostic utility irrespective of treatment, underlining the utility of serum bilirubin as a useful surrogate endpoint of outcome.

Albumin is regarded as another important and powerful biochemical predictor of liver decompensation. Low serum albumin and high bilirubin values were shown to be independent predictors of the development of cirrhosis15 and mortality.29 Recently, a global study including almost 5,000 subjects with PBC not only confirmed the strong prognostic importance of serum bilirubin, but also demonstrated that serum ALP values have significant independent and additional prognostic value in prediction of transplant-free survival.51

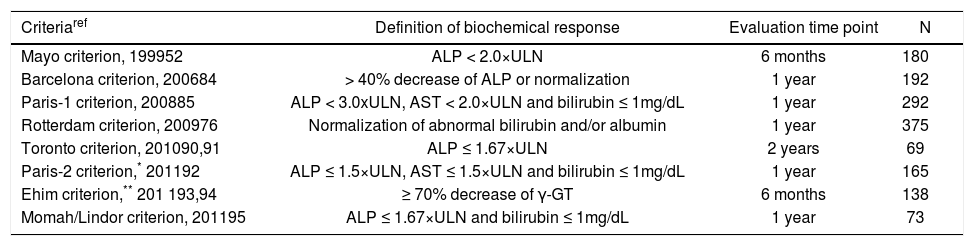

Angulo and colleagues were the first to report on the prognostic impact of changes in ALP values upon treatment with UDCA, showing that ALP values ≥ 2x upper limit of normal (ULN) after 6 months of treatment predicted future treatment failure.52 Several recent studies have also clearly demonstrated that quantitative decreases in bilirubin, albumin, ALP, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or γ-GT levels 6 months, 1 year or 2 years UDCA treatment, are predictive for improved transplant-free survival (Table 2). Responders according to these criteria were likely to have survival rates comparable with a general population. These biochemical response criteria are useful and now generally accepted tools for stratification purposes and for identifying patients in need of additional treatment.

Biochemical response criteria for risk stratification in UDCA treated patients.

| Criteriaref | Definition of biochemical response | Evaluation time point | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayo criterion, 199952 | ALP < 2.0×ULN | 6 months | 180 |

| Barcelona criterion, 200684 | > 40% decrease of ALP or normalization | 1 year | 192 |

| Paris-1 criterion, 200885 | ALP < 3.0xULN, AST < 2.0×ULN and bilirubin ≤ 1mg/dL | 1 year | 292 |

| Rotterdam criterion, 200976 | Normalization of abnormal bilirubin and/or albumin | 1 year | 375 |

| Toronto criterion, 201090,91 | ALP ≤ 1.67×ULN | 2 years | 69 |

| Paris-2 criterion,* 201192 | ALP ≤ 1.5×ULN, AST ≤ 1.5×ULN and bilirubin ≤ 1mg/dL | 1 year | 165 |

| Ehim criterion,** 201 193,94 | ≥ 70% decrease of γ-GT | 6 months | 138 |

| Momah/Lindor criterion, 201195 | ALP ≤ 1.67×ULN and bilirubin ≤ 1mg/dL | 1 year | 73 |

Mathematical prediction models, either time-fixed or time-dependent, have been developed to predict the probability of survival using biochemical, clinical and/or histological features. Serum bilirubin and age are the main components of almost all proposed models.11,16,53–56

Roll, et al. showed that age at time of diagnosis, presence of hepatomegaly and increased serum bilirubin were all independently associated with survival.16 Notably, portal fibrosis was an independent predictor of prolonged survival in this study. Other studies identified (log)bilirubin,32,56.57 variceal bleeding32 albumin, age and ascites57 as independent predictors of outcome.

Bonsel, et al. constructed a prognostic model incorporating nine variables: log(bilirubin), age, albumin, HBsAg, neurological complications, varices, ascites, clinical icterus and Quick-time prolongation.54

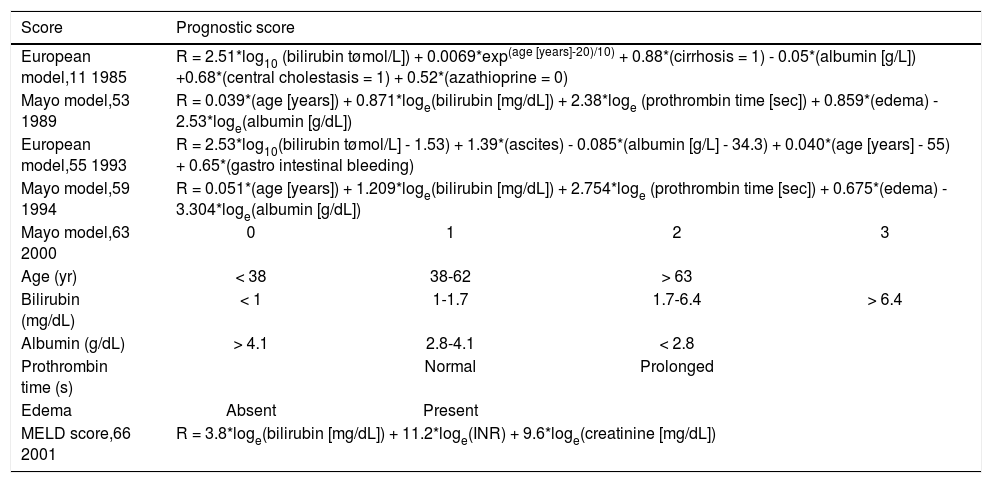

Two well defined and cross-validated models, the European Model and the Mayo risk score, are summarized in table 3. The European model was published in 1985 by Christensen, et al. based on data from 248 patients, originally included in an azathioprine placebo-controlled trial.11 This time-fixed model included age at time of diagnosis, bilirubin, albumin, cirrhosis, central cholestasis and usage of azathioprine at baseline. In 1993 this group published two time-dependent models; one included only clinical and biochemical variables (bilirubin, ascites, albumin, age and gastrointestinal bleeding) and one extended version, included additionally IgM and two histological variables (central cholestasis and cirrhosis).

Important prediction models in primary biliary cirrhosis.

| Score | Prognostic score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European model,11 1985 | R = 2.51*log10 (bilirubin tømol/L]) + 0.0069*exp(age [years]-20)/10) + 0.88*(cirrhosis = 1) - 0.05*(albumin [g/L]) +0.68*(central cholestasis = 1) + 0.52*(azathioprine = 0) | |||

| Mayo model,53 1989 | R = 0.039*(age [years]) + 0.871*loge(bilirubin [mg/dL]) + 2.38*loge (prothrombin time [sec]) + 0.859*(edema) - 2.53*loge(albumin [g/dL]) | |||

| European model,55 1993 | R = 2.53*log10(bilirubin tømol/L] - 1.53) + 1.39*(ascites) - 0.085*(albumin [g/L] - 34.3) + 0.040*(age [years] - 55) + 0.65*(gastro intestinal bleeding) | |||

| Mayo model,59 1994 | R = 0.051*(age [years]) + 1.209*loge(bilirubin [mg/dL]) + 2.754*loge (prothrombin time [sec]) + 0.675*(edema) - 3.304*loge(albumin [g/dL]) | |||

| Mayo model,63 2000 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Age (yr) | < 38 | 38-62 | > 63 | |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | < 1 | 1-1.7 | 1.7-6.4 | > 6.4 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | > 4.1 | 2.8-4.1 | < 2.8 | |

| Prothrombin time (s) | Normal | Prolonged | ||

| Edema | Absent | Present | ||

| MELD score,66 2001 | R = 3.8*loge(bilirubin [mg/dL]) + 11.2*loge(INR) + 9.6*loge(creatinine [mg/dL]) | |||

The Mayo risk score is the most frequently used model in PBC to predict the short-term survival probability. This model was published in 1989 and cross-validated in independent cohorts.53,58 The following clinical and biochemical variables were included: age of the patient, serum bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time (PT) and severity of edema. A great advantage of this model was that liver histology was not required to calculate the risk score. The original model was based on baseline characteristics and less useful to predict survival over time. An adapted Mayo model was proposed in 1994 using the same variables (INR instead of PT) to predict short-term (< 2 years) survival or time to transplantation at any time point during follow-up.59

Data on the predictive value of the Mayo risk score after the introduction of UDCA treatment is conflicting. Kilmurry, et al. showed that in a group of 222 patients originally included in an UDCA trial, the Mayo risk score remained a useful tool for prediction of survival when calculations are repeated after 6 months treatment.60 Later studies suggested that the Mayo risk score overestimated the risk of death when applied before the start of treatment.29,61,62 In a general sense the Mayo risk score is a useful tool to stratify patients for survival and possibly for clinical trials.

A simplified model of the Mayo risk score was proposed by Kim, et al.,63 and web based applications are available for the Mayo risk score, which facilitate its usage in clinical practice.

In addition, more general prediction liver scores are used in PBC, such as the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and the Child-Turcotte-Pugh-score.64,65 The MELD score is based on serum bilirubin, serum creatinine and INR. This score was originally proposed as a prognostic marker for the outcome after placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS),66 and currently used for liver organ allocation. We believe that the MELD score does not perform well in PBC and may result in excessive waiting time.

Prediction of Portal Hypertension and Esophageal VaricesEsophageal varices may develop in the cirrhotic and pre-cirrhotic stages of PBC.68,69 Survival of PBC patients who develop esophageal varices has been reported to be poor.67,68 Patanwala, et al. reported a 5-year survival rate of 63% and 91% for patients with and without esophageal varices, respectively. The poor prognosis associated with esophageal varices may partly reflect the advanced stage of the disease in the majority of cases who develop varices, but may also be related to mortality associated with variceal bleeding. Therefore tools for timely diagnosis of varices and institution of prophylactic treatment are of obvious clinical importance.

A Mayo risk score ≥ 4.0 was seen in 93% of patients who developed esophageal varices,52 while another study identified a Mayo risk score ≥ 4.5 together with a platelet count of < 140.000/mm as independent risk factors for development of esophageal varices.69 The current AASLD guideline on PBC recommends surveillance for esophageal varices of patients with a platelet count of < 140.000/ mm3 or Mayo risk score > 4.1.6

Recently the Newcastle Varices in PBC Score was proposed to predict esophageal varices,68 based on a retrospective study including 330 PBC patients. This score was validated externally in two independent cohorts. Low albumin, low platelet count, abnormal ALP values and splenomegaly were independent predictors of varices development. An adapted score was proposed excluding splenomegaly to improve the usability in clinical practice and an online calculator is available (http://www.uk-pbc.com/resources/uk-pbc-varice-prediction-tool.html),

Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)A recent systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled relative risk of the development of HCC of 18.80 (95% CI, 10-81-26.79) for PBC patients compared with a general population, which makes HCC the most prevalent cancer in PBC.70 The outcome of patients with HCC is poor.

HCC is less frequently seen in patients who initially present with early stage disease.71,72 Jones, et al. followed-up 667 patients with early (stage I or II) and late (stage III or IV) stage disease, and both groups over the same period of time. All 16 HCC cases in this study were found in patients with advanced disease (stage III or IV) and not in patients with early disease (stage I or II).73 A similar finding was reported by Floreani, et al.74 Additional Greek and Dutch studies clearly showed that despite the differences in disease stages at baseline, all HCC cases had advanced disease at time of HCC diagnosis.75,76 However, a study from Japan of 178 HCC cases, described HCC cases among all four histological stages,77 especially in males. Histological stage at time of PBC diagnosis was independently associated with development of HCC for females, but not for males. These findings suggest that once cirrhosis occurs, risk of HCC development increases for females, but males may be at risk at any histological stage of disease. The Japanese study also showed a 10-year incidence of HCC for males versus females of 6.5% versus 2.0% (P < 0.0001). Several other studies also have demonstrated that in general males are more likely to develop HCC than females.71–73 Estrogens are considered as having possibly protective effect on HCC development.

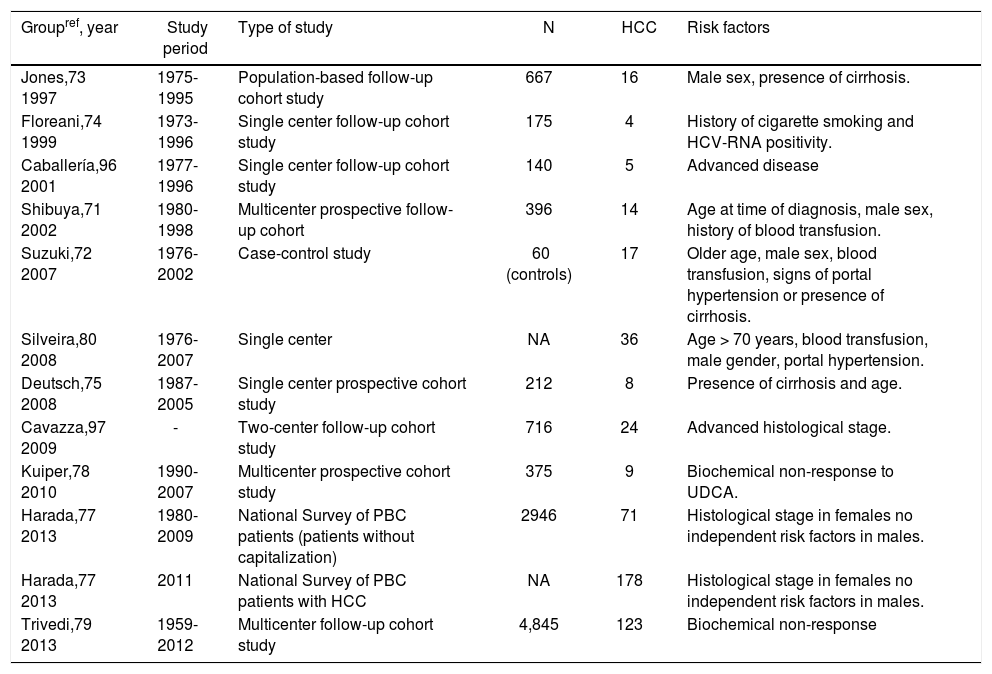

Male gender and advanced disease are the most frequently reported risk factors for HCC in PBC (Table 4). Japanese researchers proposed a highly accurate prediction model (area under the curve of 0.95) to predict development of HCC. Patients with older age, male sex, history of blood transfusion and any signs of portal hypertension or cirrhosis were more likely to develop HCC.72 These intriguing results await confirmation by other studies. Recently, absence of biochemical response in UDCA-treated PBC patients was proposed as another important risk factor for HCC.78 A large international cohort study involving 4845 PBC patients and 123 HCC cases confirmed these findings and indicated that biochemical non-response to UDCA therapy is the strongest predictive risk factor for development of HCC.79

Risk factors for development of hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Groupref, year | Study period | Type of study | N | HCC | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones,73 1997 | 1975-1995 | Population-based follow-up cohort study | 667 | 16 | Male sex, presence of cirrhosis. |

| Floreani,74 1999 | 1973-1996 | Single center follow-up cohort study | 175 | 4 | History of cigarette smoking and HCV-RNA positivity. |

| Caballería,96 2001 | 1977-1996 | Single center follow-up cohort study | 140 | 5 | Advanced disease |

| Shibuya,71 2002 | 1980-1998 | Multicenter prospective follow-up cohort | 396 | 14 | Age at time of diagnosis, male sex, history of blood transfusion. |

| Suzuki,72 2007 | 1976-2002 | Case-control study | 60 (controls) | 17 | Older age, male sex, blood transfusion, signs of portal hypertension or presence of cirrhosis. |

| Silveira,80 2008 | 1976-2007 | Single center | NA | 36 | Age > 70 years, blood transfusion, male gender, portal hypertension. |

| Deutsch,75 2008 | 1987-2005 | Single center prospective cohort study | 212 | 8 | Presence of cirrhosis and age. |

| Cavazza,97 2009 | - | Two-center follow-up cohort study | 716 | 24 | Advanced histological stage. |

| Kuiper,78 2010 | 1990-2007 | Multicenter prospective cohort study | 375 | 9 | Biochemical non-response to UDCA. |

| Harada,77 2013 | 1980-2009 | National Survey of PBC patients (patients without capitalization) | 2946 | 71 | Histological stage in females no independent risk factors in males. |

| Harada,77 2013 | 2011 | National Survey of PBC patients with HCC | NA | 178 | Histological stage in females no independent risk factors in males. |

| Trivedi,79 2013 | 1959-2012 | Multicenter follow-up cohort study | 4,845 | 123 | Biochemical non-response |

Surveillance strategies resulting in early diagnosis of HCC may improve outcome.80 Clearly, routine screening of all PBC patients on a regular basis is not practical. The current AASLD PBC guideline suggests that surveillance of HCC in PBC should be performed in cirrhotic patients and older men.6 Possibly, the recently reported overwhelming prognostic importance of biochemical response to UDCA may prompt future modifications of present guidelines.

Abbreviations- •

AMA: antimitochondrial antibody.

- •

ANA: anti-nuclear antibodies

- •

AST: aspartate aminotransferase

- •

Gamma-GT: gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase.

- •

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

- •

MELD: Model of End-Stage Liver Disease.

- •

PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis.

- •

PT: prothrombin time.

- •

UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

- •

ULN: upper limit of normal.

None.