Backgroud/rationale of study. Analyze safety and efficacy of angiographic-occlusion-with-sclerotherapy/ embolotherapy-without-transjugular-intrahepatic-portosystemic-shunt (TIPS) for duodenal varices. Although TIPS is considered the best intermediate-to-long term therapy after failed endoscopic therapy for bleeding varices, the options are not well-defined when TIPS is relatively contraindicated, with scant data on alternative therapies due to relative rarity of duodenal varices. Prior cases were identified by computerized literature search, supplemented by one illustrative case. Favorable clinical outcome after angiography defined as no rebleeding during follow-up, without major procedural complications.

Results. Thirty-two cases of duodenal varices treated by angiographic-occlusion-with-sclerotherapy/embolotherapy-without-TIPS were analyzed. Patients averaged 59.5 ± 12.2 years old (female = 59%). Patients presented with melena-16, hematemesis & melena-5, large varices-5, growing varices-2, ruptured varices-1, and other3. Twenty-nine patients had cirrhosis; etiologies included: alcoholism-11, hepatitis C-11, primary biliary cirrhosis-3, hepatitis B-2, Budd-Chiari-1, and idiopathic-1. Three patients did not have cirrhosis, including hepatic metastases from rectal cancer-1, Wilson’s disease-1, and chronic liver dysfunction-1. Thirty-one patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy before therapeutic angiography, including fifteen undergoing endoscopic variceal therapy. Therapeutic angiographic techniques included balloon-occludedretrograde-transvenous-obliteration (BRTO) with sclerotherapy and/or embolization-21, DBOE (double-balloon-occluded-embolotherapy)-5, and other-6. Twenty-eight patients (87.5%; 95%-confidence interval: 69-100%) had favorable clinical outcomes after therapeutic angiography. Three patients were therapeutic failures: rebleeding at 0, 5, or 10 days after therapy. One major complication (Enterobacter sepsis) and one minor complication occurred.

Conclusions. This work suggests that angiographic-occlusion-with-sclerotherapy/embolotherapy-without-TIPS is relatively effective (-90% hemostasis-rate), and relatively safe (3% major-complication-rate). This therapy may be a useful treatment option for duodenal varices when endoscopic therapy fails and TIPS is relatively contraindicated.

Endoscopic therapy using endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL),1,2 sclerotherapy,3 or endoclips4 is usually the initial therapy for recently bleeding or actively bleeding duodenal varices, but endoscopic therapy is sometimes not feasible or successful due to large variceal size,5 submucosal or deep variceal location,6,7 risks of duodenal perforation,8 awkward and inaccessible variceal position on the duodenal wall, or endoscopist inexperience. In such circumstances, percutaneous therapies offered by interventional radiology should be considered. In the presence of portosystemic hypertension, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) with or without embolization of varices.9–11 offers an effective method of reducing the backpressure responsible for maintaining variceal patency, with a reported success rate of up to 95% in patients with esophageal varices and an elevated (> 12 mmHg) portosystemic gradient.14 However efficacy of TIPS for ectopic varices is less well established. Moreover, TIPS has relative contraindications, including patients with: decompensated liver disease with highly elevated MELD (Model for End Stage Liver Disease) scores,15,16 incipient hepatic encephalopathy,17 unfavorable venous anatomy such as portal vein thrombosis,16,18 or, perhaps, low hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) which is most commonly due to heart failure.19

When TIPS is relatively contraindicated, alternatives include fluoroscopically-guided procedures such as angiographic occlusion with sclerotherapy/ embolotherapy of duodenal varices without TIPS (AOse; including balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration [BRTO] with sclerotherapy, BRTO with sclerotherapy and embolization, and double balloon occluded embolotherapy [DBOE]; and sclerotherapy/embolotherapy without balloon occlusion), or the recently proposed EUS-guided embolization.12,13 AOse may be considered during the same session when contemplating TIPS through the same transjugular route without requiring repeat catheterization. Drawbacks of AOse, however, include potential redevelopment of varices due to the untreated, underlying portal hypertension. Data on AOse are sparse and are mostly scattered in individual case reports because duodenal varices are relatively uncommon, accounting for only about 1-2% of bleeding in patients with portal hypertension.5,6 This work comprehensively analyzes this therapy to determine its safety and efficacy, and to suggest its role in treating duodenal varices.

Material and MethodsCases of duodenal varices treated by AOse were identified by computerized literature review using Pubmed, supplemented by review of gastroenterology and angiography textbooks and monographs. One case reported in a small clinical series20 was omitted because the identical case had been previously reported as a case report21 to avoid duplicate data. Favorable clinical outcome after AOse was defined as no recurrent variceal bleeding during follow-up and no major procedural complications. Patient complications were attributed to the procedure if:

- •

Attributed by the case report authors as a procedure complication, and

- •

Attributable to the procedure either because complication occurred soon after the procedure (Enterobacter sepsis 3 days after procedure), or complication is biologically plausible after procedure (duodenal ulcer after sclerotherapy attributable to sclerosant toxicity or mucosal ischemia from sclerotherapy).

This work received an exemption/approval on August 13, 2014 from William Beaumont Hospital.

Case ReportSee appendix 1.

ResultsComprehensive literature review revealed 32 cases of AOse, including the currently reported patient (Table 120–39). Patients on average were 59.5 + 12.2 years old. Nineteen patients (59%) were female. Twenty-nine patients had cirrhosis, the etiologies of which are listed in table 2. Three patients did not have cirrhosis, including one each with: liver dysfunction for 10 years,23 hepatic metastases from rectal cancer,35 and Wilson’s disease for 10 years.36 Among the 29 patients with known cirrhosis, the cirrhosis was classified as Childs-Pugh stage A-3, stage B-5, and stage C-5 (unstaged-16). Patients presented with melena-16, hematemesis & melena-5, large varices-5, growing varices-2, ruptured varices-1, melena & hematochezia-1, hematemesis-1, and hematochezia-1. Thirty-one patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) before angiography; one patient did not undergo EGD before angiography because of hypotension and encephalopathy.31 Varices were located in descending duodenum-19, third portion of duodenum-1, and fourth portion of duodenum-1 (unspecified location-11). Fifteen patients underwent endoscopic therapy before angiographic therapy, including sclerotherapy-3, endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL)-3, endoclips-3, EVL & endoclips-1, EVL & sclerotherapy-1, and unspecified-4. Among these 15 patients, therapeutic angiography was performed because endoscopic therapy initially or subsequently failed-11, and unknown/unstated reasons-4. Among the 17 patients not undergoing endoscopic therapy, angiographic therapy was indicated for duodenal varices that were large, had recently grown, had recently bled, or were actively bleeding.

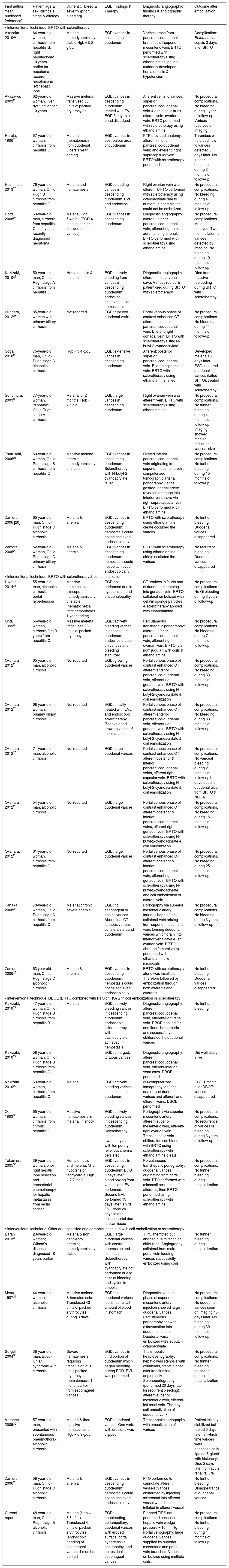

Literature review of reported cases of duodenal varices treated by angiographic occlusion by sclerotherapy/embolotherapy without TIPS during portovenography.

| First author, Year published [reference] | Patient age & sex, cirrhosis stage & etiology | Current Gl bleed & severity (prior Gl bleeding) | EGD Findings & Therapy | Diagnostic angiographic findings & angiographic therapy | Outcome after embolization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Interventional technique: BRTO with sclerotherapy | |||||

| Akasaka, 201022 | 64-year-old woman, cirrhosis from hepatitis B, right hepatectomy 10 years earlier for hepatoma; recurrent hepatoma in left hepatic lobe | Melena, hemodynamically stable Hgb = 5.2 g/dL | EGD: varices in descending duodenum | Varices arose from pancreaticoduodenal branches off superior mesenteric vein; BRTO performed with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine; patient suddenly developed hematemesis & hypotension | Complication: Enterobacter sepsis 3 days after BRTO |

| Akazawa, 200323 | 62-year-old woman, liver dysfunction for 10 years | Massive melena, transfused 80 units of packed erythrocytes | EGD: varices in descending duodenum treated with EVL; EGD 5 days later: band dislodged | Afferent veins to varices: superior pancreaticoduodenal vein & gastrocolic trunk, efferent vein: ovarian vein. BRTO performed with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 1 year of follow-up. Varices resolved on imaging |

| Haruta, 199624 | 57-year-old woman, cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Melena (hematemesis from duodenal ulcers 1 year earlier) | EGD: varices in post-bulbar area of duodenum | PTP provided anatomy: afferent (inferior pancreatico-duodenal vein) and efferent (right supracapsular vein). BRTO with sclerotherapy performed | Thrombus with no blood flow to varices detected 5 days later. No further bleeding during 3 months of follow-up |

| Hashimoto, 201325 | 76-year-old woman, Child-Pugh В cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Melena and hematemesis | EGD: bleeding varices in descending duodenum. EVL and endoclips failed | Right ovarian vein was efferent. BRTO performed with sclerotherapy using cyanoacrylate due to numerous afferents that could not be embolized | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 4 months of follow-up |

| Hotta, 200826 | 63-year-old man, cirrhosis from hepatitis С for 4 years, recently diagnosed hepatoma | Melena, Hgb = 5.4 g/dL (EGD 4 months earlier showed no varices) | EGD: varices in descending duodenum | Diagnostic angiography: afferent-inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein, efferent-right inferior adrenal to right renal. BRTO performed with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine | No procedural complications. Melena resolved. Two months later no varices detected by imaging. No bleeding during 10 months of follow-up |

| Kakizaki, 201027 | 50-year-old man, Childs-Pugh stage A cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Hematemesis & melena | EGD: actively bleeding from varices in descending duodenum; endoclips achieved initial hemos tasis | Diagnostic angiography: efferent-inferior vena cava. Varices rebled & patient died during BRTO with sclerotherapy | Died from massive rebleeding during BRTO with sclerotherapy |

| Okahara, 201228 | 85-year-old woman with primary biliary cirrhosis | Not reported | EGD: ruptured duodenal varix | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-posterior pancreaticoduodenal vein, Efferent-right gonadal vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 11 months of follow-up |

| Soga 201029 | 75-year-old man, Child-Pugh stage С alcoholic cirrhosis | Hgb = 9.4 g/dL | EGD: extensive varices in descending duodenum | Afferent: posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein. Efferent: spermatic vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine failed | Developed melena 10 days later. EGD: ruptured duodenal varices (failed BRTO), treated with sclerotherapy |

| Sonomura, 200330 | 77-year-old woman, idiopathic Child-Pugh stage A cirrhosis | Melena for 2 months. Hgb = 7.5 g/dL | EGD: large varices in descending duodenum | Right ovarian vein was efferent vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine | No procedural complications. No further bleeding during 4 months of follow-up. Imaging showed marked reduction in variceal size |

| Tsurusaki, 200621 | 60-year-old woman, Child-Pugh stage В cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Massive melena, anemia, hemodynamically unstable | EGD: varices in descending duodenum. Sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate failed | Dilated inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein originating from superior mesenteric vein, computerized tomographic arterial portography via the gastroduodenal artery revealed drainage into inferior vena cava via right supracapsular vein. BRTO performed with ethanolamine. | No procedural complications. No further bleeding during 15 months of follow-up |

| Zamora 2006 [20] | 65-year-old man, Child-Pugh stage С alcoholic cirrhosis | Melena & anemia | EGD: varices in descending duodenum; hemostasis could not be achieved endoscopically | BRTO with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine oléate occluded the varices | No further bleeding. Duodenal varices disappeared |

| Zamora 200620 | 52-year-old woman, Child-Pugh stage С primary biliary cirrhosis | Melena & anemia | EGD: varices in descending duodenum; hemostasis could not be achieved endoscopically | BRTO with sclerotherapy using ethanolamine oléate occluded the varices | No recurrent bleeding. Duodenal varices disappeared |

| • Interventional technique: BRTO with sclerotherapy & coil embolization | |||||

| Hwang, 201431 | 55-year-old man, alcoholic cirrhosis, portal hypertension | Massive hematochezia, syncope, hemodynamically unstable (hematochezia from hemorrhoids 1 year earlier) | EGD not performed due to hypotension and encephalopathy | CT: varices in fourth part of duodenum draining into gonadal vein. BRTO: collateral embolized with gelatin sponge particles & sclerotherapy applied with ethanolamine | No procedural complications. No Gl bleeding during 3 years of follow-up |

| Ohta, 199932 | 56-year-old woman, cirrhosis for 10 years from hepatitis С | Massive melena; transfused 28 units of packed erythrocytes | EGD: actively bleeding varices in descending duodenum; endoclips placed on varices and bleeding stabilized | Percutaneous transhepatic portography: afferent-inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein, efferent-right ovarian vein. BRTO (via right jugular) with coils & ethanolamine | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 7 months of follow-up |

| Okahara 201228 | 65-year-old man, alcoholic cirrhosis | Not reported | EGD: growing duodenal varices | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-anterior pancreatico-duodenal vein, efferent-right gonadal vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate & coil embolization | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 83 months of follow-up |

| Okahara 201228 | 68-year-old woman, primary biliary cirrhosis | Not reported | EGD: initially treated with EVL and endoscopic sclerotherapy. Redeveloped growing varices 6 months later | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-anterior pancreatico-duodenal vein, efferent-right gonadal vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate & coil embolization | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 33 months of follow-up |

| Okahara 201228 | 71-year-old man, alcoholic cirrhosis | Not reported | EGD: large duodenal varices | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-posterior & inferior pancreaticoduodenal veins, efferent-right capsular vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate & coil embolization | No procedural complications. No variceal bleeding during 2 months of follow-up but developed a duodenal ulcer from BRTO & NBCA |

| Okahara 201228 | 54-year-old man, alcoholic cirrhosis | Not reported | EGD: large duodenal varices | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-posterior & inferior pancreaticoduodenal veins, efferent-right gonadal vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate & coil embolization | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 16 months of follow-up |

| Okahara, 201228 | 61-year-old woman, cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Not reported | EGD: large duodenal varices | Portal venous phase of contrast enhanced CT: afferent-posterior & inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein, efferent-right gonadal vein. BRTO with sclerotherapy using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and coil embolizaton of afferent vein | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 25 months of follow-up |

| Tanaka, 200833 | 78-year-old woman, Child-Pugh stage A cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Melena; chronic severe anemia | EGD: no esophageal or gastric varices. Abdominal CT: tortuous venous collaterals around duodenum | Portography via superior mesenteric artery: tortuous hepatofugal collateral vein arising from superior mesenteric vein, forming duodenal varices which drain into inferior vena cava & left ovarian vein. BRTO (through femoral vein) performed with ethanolamine & microcoils | No procedural complications. No bleeding during 3 years of follow-up |

| Zamora 200620 | 63 year old man, Child-Pugh stage С alcoholic cirrhosis | Melena & anemia | EGD: varices in descending duodenum; hemostasis could not be achieved endoscopically | BRTO with sclerotherapy alone was insufficient. Therefore followed by embolization through both afferents and efferents | No further bleeding. Duodenal varices disappeared |

| • Interventional technique: DBOE (BRTO combined with PTO or TIO) with coil embolization or sclerotherapy | |||||

| Kakizaki, 201027 | 47-year-old woman, Child-Pugh stage В cirrhosis from hepatitis В | Melena | EGD: actively bleeding varices in descending duodenum; endoscopic sclerotherapy with cyanoacrylate achieved hemostasis | Diagnostic angiography: afferent-pancreaticoduodenal vein, efferent-right renal vein. DBOE applied for additional hemostasis and successfully obliterated the duodenal varices | No further bleeding |

| Kakizaki, 201027 | 58-year-old woman, Child-Pugh stage В cirrhosis from hepatitis С | EGD: enlarged, tortuous varices | Diagnostic angiography: afferent-pancreaticoduodenal vein, efferent-inferior vena cava. DBOE performed | Did well after; alive | |

| Kakizaki 201027 | 63-year-old woman, cirrhosis from hepatitis С | Melena | EGD: actively bleeding varices in descending duodenum | 3D-computerized tomography: defined anatomy of duodenal varices and afferent and efferent veins. DBOE performed | EGD 1 month after DBOE: varices disappeared |

| Ota, 199934 | 65-year-old woman, cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis С | Massive hematemesis & melena, in shock | EGD: actively bleeding varices in descending duodenum. Sclerotherapy using cyanoacrylate with temporary relief but anemia persisted | Portography via superior mesenteric artery: afferent-superior mesenteric vein, efferent-right ovarian vein. Transileocolic vein obliteration combined with BRTO using sclerotherapy with ethanolamine oléate | No procedural complications. No recurrence of varices or bleeding during 3 years of follow-up |

| Takamura, 200535 | 39-year-old woman, prior right hepatic lobe resection and transarterial chemotherapy for hepatic metastases from rectal cancer | Hematemesis and melena. Mild hypotension, tachycardia, Hgb = 7.7 mg/dL | EGD: varices in descending duodenum; EGD 3 days later: blood oozing from varices and EVL performed. Second EVL performed 13 days later. Third EVL done 20 days later but unsuccessful due to scar tissue | Percutaneous transhepatic portography: duodenal varices originating from portal vein. PTO performed with microcoil occlusion of afferents, then BRTO performed using sclerotherapy with ethanolamine | No procedural complications. No further bleeding during hospitalization |

| • Interventional technique: Other or unspecified angiographic technique with coil embolization or sclerotherapy | |||||

| Baran 201336 | 29-year-old woman; Wilson’s disease diagnosed 10 years earlier | Melena & iron deficiency anemia; hemodynamically stable | EGD: large duodenal varices with central depression and fibrin cap. Sclerotherapy with cyanoacrylate not performed due to risks of bleeding and systemic embolism | TIPS attempted but aborted due to technical difficulties. Angiography: collateral from main portal vein feeding varices successfully embolized using coils | No further bleeding during hospitalization |

| Menu, 198737 | 44-year-old woman, alcoholic cirrhosis | Massive melena & hematemesis. Transfused 43 units of packed erythrocytes during 3 days | EGD: no duodenal varices identified, small amount of blood in stomach | Diagnostic: venous phase of superior mesenteric artery injection showed large duodenal varices. Percutaneous portography showed extravasation into duodenal lumen; Duodenal varix embolized with isobutyl-cyanoacrylate | No procedural complications. No duodenal varices seen on imaging 45 days later. No bleeding during 30 months of follow-up |

| Selçuk 200438 | 38-year-old man, Budd-Chiari syndrome with cirrhosis | Severe hematemesis requiring transfusion of 12 units packed erythrocytes (hematemesis 1 month earlier from esophageal varices) | EGD: varices in third portion of duodenum which began bleeding during EGD. EVL was performed | Transhepatic heaptovenography: hepatic vein stenosis with collaterals, stents placed after transluminal angioplasty. Splenoportography (performed 20 days later for recurrent bleeding): afferent-superior mesenteric vein, efferent-left renal vein. Therapy: coil embolization of duodenal varix | No procedural complications. No further bleeding episodes during hospitalization |

| Verbeeck, 200939 | 57-year-old man, presented with spontaneous pneumothorax, alcoholic cirrhosis | Melena & then massive hematochezia, Hgb = 6.9 g/dL | EGD: duodenal varices, One varix with erosions was clipped | Transhepatic portography with embolization of varices | Patient initially stabilized but rebled 5 days later, at which time varices were endoscopically ligated & glued with histoacryl. Died 2 days later from acute renal failure |

| Zamora 200620 | 58-year-old man, Child-Pugh stage C alcoholic cirrhosis | Melena & anemia | EGD: varices in descending duodenum; hemostasis could not be achieved endoscopically | PTO performed to cannulate afferent vessels; varices obliterated by injecting sclerosant into afferent vessel while balloon inflated in efferent vessel | No further bleeding. Disappearance of duodenal varices |

| Current report | 48-year-old man, Child-Pugh stage B alcoholic cirrhosis | Melena (Hgb = 3.8 g/dL). Transfused 4 units of packed erythrocytes (endoscopic banding of esophageal varices 4 months earlier) | EGD: nonbleeding, periampullary, duodenal varices with eroded surface, portal hypertensive gastropathy, and no residual esophageal varices | Planned TIPS not performed because hepatic vein wedge pressure = 10 mmHg. Portal venography: large duodenal varices supplied by superior mesenteric and portal vein branches. Varices embolized using multiple coils. | No procedural complications. No further bleeding during 4 months of follow-up |

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy. BRTO: balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. PTO: percutaneous transhepatic obliteration. DBOE: double balloon occluded embolotherapy. TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. EVL: endoscopic variceal ligation. CT: computerized tomography. Hgb: hemoglobin.

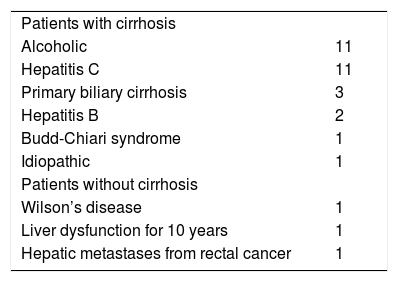

Etiologies of liver disease/portal hypertension among 32 reported patients undergoing angiographic occlusion with sclerotherapy/embolotherapy without TIPS for duodenal varies.

| Patients with cirrhosis | |

| Alcoholic | 11 |

| Hepatitis C | 11 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 3 |

| Hepatitis B | 2 |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 1 |

| Idiopathic | 1 |

| Patients without cirrhosis | |

| Wilson’s disease | 1 |

| Liver dysfunction for 10 years | 1 |

| Hepatic metastases from rectal cancer | 1 |

Diagnostic radiographic techniques and findings before angiographic therapy are detailed in table 1. Therapeutic AOse techniques included BRTO with sclerotherapy or coil embolization-16, BRTO with sclerotherapy & coil embolization-5, DBOE-5, and other-6, of which five did not use balloon occlusion (procedural details specified in table 1). By definition, no patient had undergone successful TIPS; one patient had undergone attempted TIPS which failed.36

Three patients experienced therapeutic failures, including: variceal rebleeding during BRTO with sclerotherapy that was fatal,27 rebleeding 5 days after embolization with death 2 days thereafter from acute renal failure.39 and rebleeding 10 days after BRTO from ruptured varices successfully treated with endoscopic sclerotherapy.29 One patient experienced a major procedural complication: Enterobacter sepsis 3 days after BRTO.22 One patient experienced a minor complication: nonbleeding duodenal ulcer detected 2 months after BRTO with sclerotherapy.28 This complication is attributable to the sclerotherapy from leakage of the injected toxic sclerosant into mucosal tissue or from mucosal ischemia from vessel occlusion. Twenty-eight of the 32 patients had favorable clinical outcomes, without rebleeding or major complications (rate = 87.5%; 95%-confidence interval: 69-100%, Fisher’s exact test), including 19 who did not bleed during a mean follow-up of 19.4 ± 19.5 months, and 9 others who did not rebleed during the index hospitalization (without further follow-up).

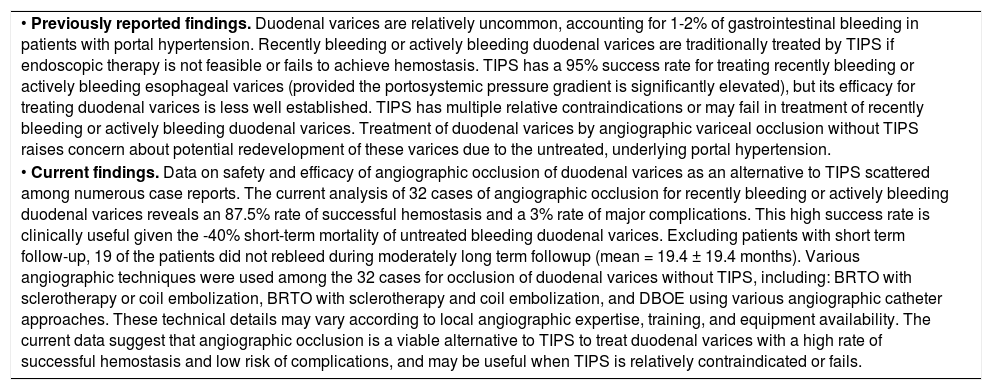

DiscussionWhen TIPS is relatively contraindicated to treat recently bleeding or actively bleeding duodenal varices, various local angiographic procedures without TIPS, herein labeled AOse, become potential alternative therapies. These alternatives might have been considered short-term, stop-gap measures with a poor intermediate-term prognosis because these local therapies do not relieve the underlying portal hypertension responsible for the development of ectopic varices. The major finding in this analysis of 32 cases is that this therapy is a viable alternative to TIPS with a relatively high rate of short term hemostasis, reasonably low rate of serious complications, and a potentially relatively high rate of intermediate-term success. The currently reported 87.5% rate of successful outcome with AOse compares extremely favorably with the ~40% short-term mortality of untreated bleeding duodenal varices.40 The key current findings and prior findings about AOse are summarized in table 3.

Key findings regarding angiographic occlusion of duodenal varices as an alternative to TIPS.

| • Previously reported findings. Duodenal varices are relatively uncommon, accounting for 1-2% of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with portal hypertension. Recently bleeding or actively bleeding duodenal varices are traditionally treated by TIPS if endoscopic therapy is not feasible or fails to achieve hemostasis. TIPS has a 95% success rate for treating recently bleeding or actively bleeding esophageal varices (provided the portosystemic pressure gradient is significantly elevated), but its efficacy for treating duodenal varices is less well established. TIPS has multiple relative contraindications or may fail in treatment of recently bleeding or actively bleeding duodenal varices. Treatment of duodenal varices by angiographic variceal occlusion without TIPS raises concern about potential redevelopment of these varices due to the untreated, underlying portal hypertension. |

| • Current findings. Data on safety and efficacy of angiographic occlusion of duodenal varices as an alternative to TIPS scattered among numerous case reports. The current analysis of 32 cases of angiographic occlusion for recently bleeding or actively bleeding duodenal varices reveals an 87.5% rate of successful hemostasis and a 3% rate of major complications. This high success rate is clinically useful given the -40% short-term mortality of untreated bleeding duodenal varices. Excluding patients with short term follow-up, 19 of the patients did not rebleed during moderately long term followup (mean = 19.4 ± 19.4 months). Various angiographic techniques were used among the 32 cases for occlusion of duodenal varices without TIPS, including: BRTO with sclerotherapy or coil embolization, BRTO with sclerotherapy and coil embolization, and DBOE using various angiographic catheter approaches. These technical details may vary according to local angiographic expertise, training, and equipment availability. The current data suggest that angiographic occlusion is a viable alternative to TIPS to treat duodenal varices with a high rate of successful hemostasis and low risk of complications, and may be useful when TIPS is relatively contraindicated or fails. |

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. BRTO: balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. DBOE: double balloon occluded embolotherapy.

The currently reported patient (Appendix 1) developed persistent melena from de novo duodenal varices. He had a history of prior esophageal EVL, a reported risk factor for ectopic varices secondary to redistribution of pressure and blood flow to alternative, ectopic anastomoses.40–42 The patient was referred for urgent TIPS which was deemed not indicated because the portosystemic gradient was found to be not significantly elevated during transhepatic portal venography. The varices were obliterated during the same session by coil embolization without balloon occlusion of the main supplying vessels. Hemostasis persisted for 4 months of follow-up. A similar procedure was reported by Baran, et al. after an unsuccessful attempt at TIPS.36

This work has limitations. First, the data are subject to reporting bias due to its retrospective, case-based nature from various institutions with variable angiographic expertise. The data would be more secure if prospectively obtained at one institution. However, accumulation of sufficient number of cases at one institution is unlikely because of the relative rarity of duodenal varices. Second, analyzed reports had variable data (e.g. variable follow-up period), and some reports had missing data (e.g. no follow-up after index hospitalization). Third, the reported cases involve various procedural variations. However, all the techniques are permutations of angiographic variceal occlusion without TIPS and these permutations are required because of variable duodenal variceal anatomy and variable institutional expertise. Fourth, the number of analyzed cases is only moderate, resulting in a moderately large confidence interval for the rate of successful angiographic therapy. Despite these limitations, this work constitutes the largest review of AOse, contributes new data about AOse, and provides some guidelines based on the analyzed data. Given the efficacy and relative safety of AOse reported in this review, AOse might be a useful alternative to TIPS when TIPS is relatively contraindicated, the portosystemic gradient is low, or TIPS is unsuccessful.

Conflicts of InterestNone for all authors. In particular, this paper does not discuss any confidential pharmaceutical industry data reviewed by Dr. Cappell as a consultant for the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) Advisory Committee on Gastrointestinal Drugs.

IRB: William Beaumont Hospital IRB exemption/ approval received 8/13/14.

Source of FundingNone.

Appendix 1. Case report.A 48-year-old man with alcoholic cirrhosis (MELD score = 8), status-post successful endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) 4 months earlier of large, actively bleeding, esophageal varices without portal hypertensive gastropathy or duodenal varices observed at that esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), was admitted for melena (hemoglobin = 3.8 g/dL). Physical examination revealed stable vital signs, pallor, and multiple stigmata of chronic liver disease. Serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin were mildly elevated, without coagulopathy. Hemoglobin rose to 8.1 g/dL after transfusing 4 units of packed erythrocytes. EGD revealed nonbleeding, periampullary, duodenal varices with one eroded surface (Figure 1), portal hypertensive gastropathy, and no residual esophageal varices. Endoscopic therapy was deferred due to large duodenal variceal size, awkward variceal position, and endoscopist inexperience with banding duodenal varices. Colonoscopy revealed no lesions. The patient received octreotide, ciprofloxacin, and carvedilol.

Videophotograph taken during esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a 48-year-old man with alcoholic cirrhosis reveals nonbleeding, large, ectatic, periampullary veins containing a saccular dilatation diagnostic of duodenal varices. Note the stigma of recent hemorrhage of an eroded surface on the varix at the 8-o’clock position.

During intended TIPS, performed for ongoing melena, using the internal jugular vein for access, the hepatic-veinwedge-pressure = 10 mmHg, and portosystemic-pressure-gradient = 8 mmHg. Portal venography revealed large duodenal varices supplied by confluence of superior mesenteric and portal vein branches and draining via the gonadal vein (Figure 2A). TIPS was not performed because the portosystemic pressure gradient was not significantly elevated. Instead, a microcatheter was manipulated into the main venous branch supplying the duodenal varices and retrograde embolization of this vessel was performed using multiple microcoils (Figure 2B), with absent blood flow after embolization (Figure 2C). The portosystemic-pressure-gradient remained at only 3 mmHg after embolization, again indicating no need for TIPS. Pathologic examination of multiple, random, intraprocedural liver biopsies confirmed the cirrhosis. The patient stopped bleeding post-embolization, was discharged 3 days later, and experienced no gastrointestinal bleeding during the ensuing 4 months.

Findings during portal venography with coil embolization. A. Injection of contrast during portal venography demonstrates large, ectatic duodenal varices supplied by the confluence of the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein branches. There is no contrast extravasation. B. Portal venography demonstrates presence of multiple coils during embolization of large, ectatic duodenal varices. C. Injection of contrast during portal venography demonstrates no flow through duodenal varices after coil embolization.