Introduction. Hyponatremia is associated with high mortality and predicts hepatic encephalopathy but its effect on health-related quality of life remains to be established.

Material and methods. In this study we prospectively analyzed the relationship between hyponatremia, clinical features and quality of life in a cohort of 116 patients with cirrhosis. Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire and Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey were performed to assess quality of life. Evaluation of hepatic encephalopathy included West-Haven criteria, Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score and Critical Flicker Frequency analysis. Severity of liver disease was assessed with Child-Pugh score and MELD. Univariate and multivariate analysis were implemented to evaluate the influence of analyzed factors on quality of life.

Results. Multivariate analysis has identified serum natremia, Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score, Critical Flicker Frequency and severity of liver disease measured with MELD and Child-Pugh score as independent factors affecting quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. West Heaven criteria failed to show the relationship with quality of life in analyzed subjects. Serum kalemia showed correlation with neither quality of life, hepatic encephalopathy nor severity of the disease.

Conclusion. In patients with cirrhosis serum natremia along with severity of liver disease and hepatic encephalopathy exerts a significant effect on patients’ quality of life.

Various factors such as ascites, overt hepatic encephalopathy (HE) or anemia may impair daily functioning of patients with liver cirrhosis,1 however the effects of serum electrolytes or minimal HE, commonly seen in patients with end-stage liver disease on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) have not yet been fully established.

Hyponatremia is a serious complication of liver cirrhosis.2,3 It is associated with a high morbidity and mortality both before and post transplantation.4–8 The main underlying pathology leading to hyponatremia in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis is an impaired solute-free water clearance caused by circulatory dysfunction and abnormal non-osmotic hypersecretion of vasopressin.9 It results in renal retention of water that is out of proportion to the retention of sodium, producing expanded extracellular fluid volume with ascites and edema. This pathogenic pathway expresses a strong relationship with the development of hepatorenal syndrome which is one of the most dreadful complication of cirrhosis.10

Serum pre-transplant potassium level (kalemia) above 5 mmol/L has been recently found to be an independent negative predictor of death after liver transplantation. This referred also to the values at the upper limit of a still normal range.11 Literature on the effect of natremia and kalemia on HRQoL in liver cirrhosis is extremely scanty.12,13

Although overt HE is a well known factor affecting HRQoL, the effect of minimal HE on patients HRQL remains controversial.14–16

In order to address these issues we analyzed the effect of several clinically important factors on HRQL in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Material and MethodsPatientsOne hundred thirty four consecutive patients with liver cirrhosis treated at our institution were prospectively assessed for this study. Cirrhosis was confirmed with liver biopsy and/or typical presentation on imaging studies. Child–Pugh score and MELD were used in the assessment of the severity of liver disease. Exclusion criteria comprised factors impairing the neuropsychological examination, such as consumption of psychotropic drugs, active alcohol misuse, vision disturbance, other than liver disease severe medical problems influencing HRQoL (such as decompensated diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency requiring dialyses, malignancy, heart failure ≥ NYHA II, rheumatoid arthritis or asthma) and inability to complete the questionnaires. As eighteen patients met the exclusion criteria 116 subjects were eventually included into the project.

Assessment of HRQoLChronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) were performed in all patients. The CLDQ, a disease-specific measure of HRQoL, evaluates the impact of chronic liver disease on the patient’s daily living.17 It consists of 29 items grouped into 6 domains (abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, fatigue, activity, emotional functions and worry). The scores for the six domains and the CLDQ summary score are calculated, with the results presented on a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL.

SF-36 is a generic HRQoL tool, that has been widely used and validated in various conditions.18 It contains 36 items grouped into domains of physical health (physical functioning, role limitation-physical, bodily pain and general health) and mental health (vitality, social functioning, role limitation-emotional and mental health). Each item is scored between 0 and 100 points, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL. Points represent the percentage of total possible score achieved. The scores from those items are then averaged together, for a calculation of a final score within each of the eight health domains measured. Two summary scores, physical component and mental component are obtained. A license was obtained for the use of the SF-36 questionnaire in this study.

Evaluation of HEThe evaluation of HE included West Haven criteria,19 psychometric and neurophysiological assessment based on two recently recommended methods: the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES) and critical flicker frequency (CFF).20–23

PHES, a battery of 5 paper-pencil tests (number connection test-A, number connection test-B, the digit symbol test, the line tracing test and the serial dotting test) is a sensitive, valid and reliable neuropsychological tool for the quantification of minimal HE.23–25 Because of the influence of the ethnicity on PHES previously defined Polish normative data have been used to evaluate obtained data.15 According to our standardization the summary PHES score was calculated as the sum of six subtest and ranged between + 16 and - 18 points. The abnormal cut-off value of the mean PHES sum was set at - 5 points. A detailed description of PHES scoring system is presented elsewhere.15

CFF has been used for a measurement of a broad variety of neurophysiological qualities associated with function of cerebral cortex.26 It has been recently found to be an objective, reproducible and sensitive diagnostic tool for the assessment of minimal HE.21,27–29 CFF values were estimated using a validated analyzer (HEPAtonorm Analyzer®; Lab Automation Network, Tübingen, Germany). All patients completed the tests after an appropriate explanation and demonstration. According to data obtained by Kircheis, et al. CFF mean values < 39 Hz was considered abnormal.30 Minimal HE was diagnosed when at least one of two above tests was abnormal.

EthicsWritten informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the appropriate ethics committee of Pomeranian Medical University and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (6th revision, 2008).

StatisticsPatient measures are reported as means ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using Stat-View-5 Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, US) and included χ2, χ2 with Yates correction, Fisher’s exact and ANOVA analysis. Categorical data were compared using Levene’s test for equality of variances, and both pooled-variances and separate-variances t-tests for equality of means. Correlation-coefficient analysis was performed with Spearman test. Independent predictive factors of Mental and Physical components of SF-36 and CLDQ summary score were identified by forward stepwise regression method. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

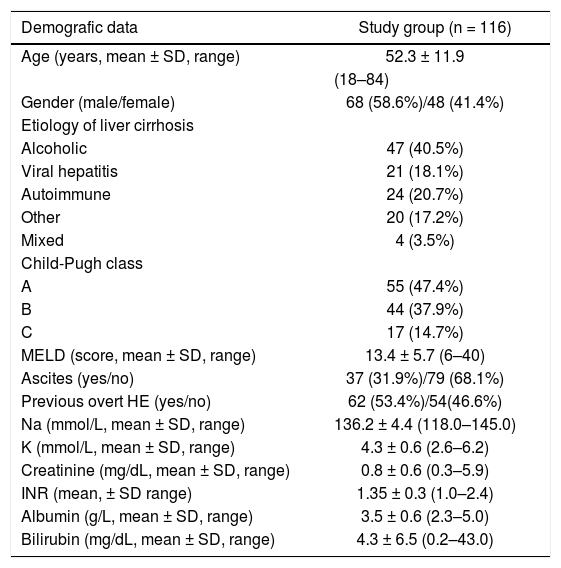

ResultsOut of the 116 analyzed patients 68 (58.6 %) were males and 48 (41.4%) females, aged 18–84 years (52.3 ± 11.9 years). Demographic and clinical data on included subjects are shown in table 1. Neither age nor alcoholic etiology of cirrhosis influenced HRQoL in analyzed patients, however women showed impaired quality of life on SF-36 when compared to men (p < 0.05 for Physical Component, p < 0.01 for Mental Component). These data are shown in tables 2–4.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical data of cirrhotic patients.

| Demografic data | Study group (n = 116) |

|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD, range) | 52.3 ± 11.9 |

| (18–84) | |

| Gender (male/female) | 68 (58.6%)/48 (41.4%) |

| Etiology of liver cirrhosis | |

| Alcoholic | 47 (40.5%) |

| Viral hepatitis | 21 (18.1%) |

| Autoimmune | 24 (20.7%) |

| Other | 20 (17.2%) |

| Mixed | 4 (3.5%) |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 55 (47.4%) |

| B | 44 (37.9%) |

| C | 17 (14.7%) |

| MELD (score, mean ± SD, range) | 13.4 ± 5.7 (6–40) |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 37 (31.9%)/79 (68.1%) |

| Previous overt HE (yes/no) | 62 (53.4%)/54(46.6%) |

| Na (mmol/L, mean ± SD, range) | 136.2 ± 4.4 (118.0–145.0) |

| K (mmol/L, mean ± SD, range) | 4.3 ± 0.6 (2.6–6.2) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL, mean ± SD, range) | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0.3–5.9) |

| INR (mean, ± SD range) | 1.35 ± 0.3 (1.0–2.4) |

| Albumin (g/L, mean ± SD, range) | 3.5 ± 0.6 (2.3–5.0) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL, mean ± SD, range) | 4.3 ± 6.5 (0.2–43.0) |

MELD: Model of end-stage liver disease. INR: international ratio.

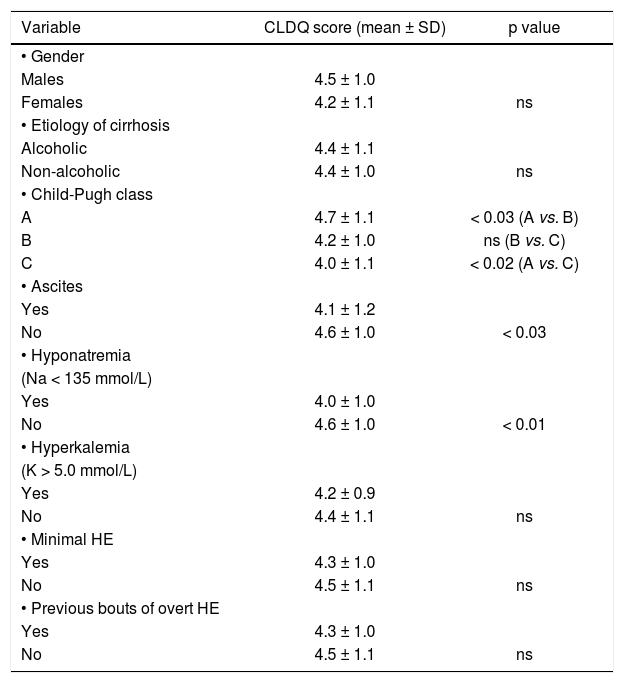

Relationship between CLDQ score and analyzed factors.

| Variable | CLDQ score (mean ± SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| • Gender | ||

| Males | 4.5 ± 1.0 | |

| Females | 4.2 ± 1.1 | ns |

| • Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| Alcoholic | 4.4 ± 1.1 | |

| Non-alcoholic | 4.4 ± 1.0 | ns |

| • Child-Pugh class | ||

| A | 4.7 ± 1.1 | < 0.03 (A vs. B) |

| B | 4.2 ± 1.0 | ns (B vs. C) |

| C | 4.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.02 (A vs. C) |

| • Ascites | ||

| Yes | 4.1 ± 1.2 | |

| No | 4.6 ± 1.0 | < 0.03 |

| • Hyponatremia | ||

| (Na < 135 mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 4.0 ± 1.0 | |

| No | 4.6 ± 1.0 | < 0.01 |

| • Hyperkalemia | ||

| (K > 5.0 mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 4.2 ± 0.9 | |

| No | 4.4 ± 1.1 | ns |

| • Minimal HE | ||

| Yes | 4.3 ± 1.0 | |

| No | 4.5 ± 1.1 | ns |

| • Previous bouts of overt HE | ||

| Yes | 4.3 ± 1.0 | |

| No | 4.5 ± 1.1 | ns |

CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire. HE: hepatic encephalopathy.

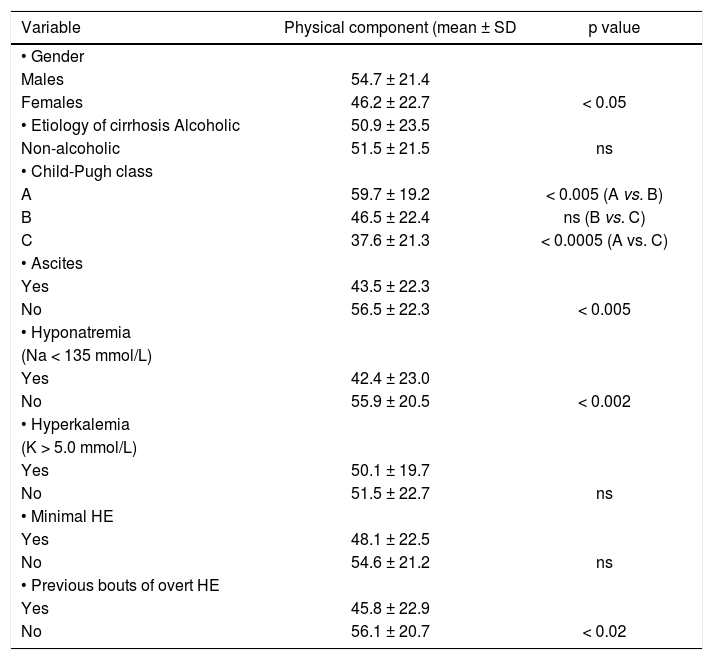

Relationship between Physical component of SF-36 score and analyzed factors.

| Variable | Physical component (mean ± SD | p value |

|---|---|---|

| • Gender | ||

| Males | 54.7 ± 21.4 | |

| Females | 46.2 ± 22.7 | < 0.05 |

| • Etiology of cirrhosis Alcoholic | 50.9 ± 23.5 | |

| Non-alcoholic | 51.5 ± 21.5 | ns |

| • Child-Pugh class | ||

| A | 59.7 ± 19.2 | < 0.005 (A vs. B) |

| B | 46.5 ± 22.4 | ns (B vs. C) |

| C | 37.6 ± 21.3 | < 0.0005 (A vs. C) |

| • Ascites | ||

| Yes | 43.5 ± 22.3 | |

| No | 56.5 ± 22.3 | < 0.005 |

| • Hyponatremia | ||

| (Na < 135 mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 42.4 ± 23.0 | |

| No | 55.9 ± 20.5 | < 0.002 |

| • Hyperkalemia | ||

| (K > 5.0 mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 50.1 ± 19.7 | |

| No | 51.5 ± 22.7 | ns |

| • Minimal HE | ||

| Yes | 48.1 ± 22.5 | |

| No | 54.6 ± 21.2 | ns |

| • Previous bouts of overt HE | ||

| Yes | 45.8 ± 22.9 | |

| No | 56.1 ± 20.7 | < 0.02 |

HE: hepatic encephalopathy.

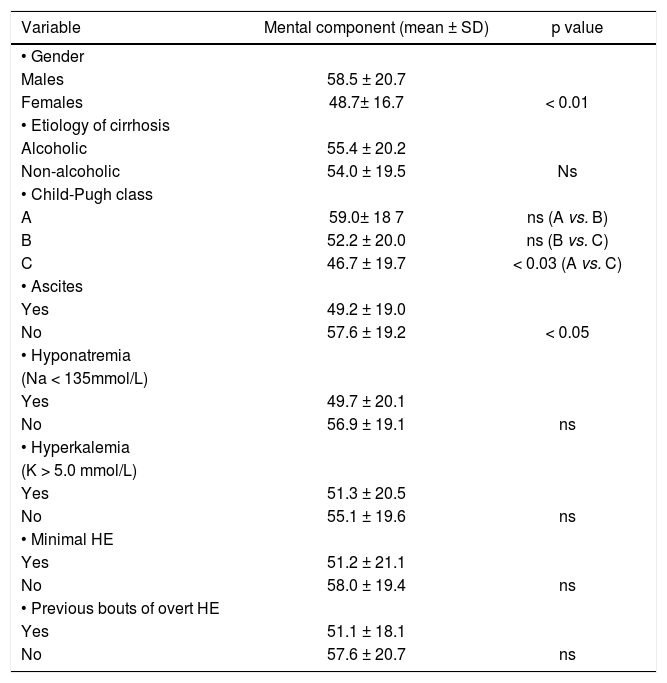

Relationship between Mental component of SF-36 score and analyzed factors.

| Variable | Mental component (mean ± SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| • Gender | ||

| Males | 58.5 ± 20.7 | |

| Females | 48.7± 16.7 | < 0.01 |

| • Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| Alcoholic | 55.4 ± 20.2 | |

| Non-alcoholic | 54.0 ± 19.5 | Ns |

| • Child-Pugh class | ||

| A | 59.0± 18 7 | ns (A vs. B) |

| B | 52.2 ± 20.0 | ns (B vs. C) |

| C | 46.7 ± 19.7 | < 0.03 (A vs. C) |

| • Ascites | ||

| Yes | 49.2 ± 19.0 | |

| No | 57.6 ± 19.2 | < 0.05 |

| • Hyponatremia | ||

| (Na < 135mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 49.7 ± 20.1 | |

| No | 56.9 ± 19.1 | ns |

| • Hyperkalemia | ||

| (K > 5.0 mmol/L) | ||

| Yes | 51.3 ± 20.5 | |

| No | 55.1 ± 19.6 | ns |

| • Minimal HE | ||

| Yes | 51.2 ± 21.1 | |

| No | 58.0 ± 19.4 | ns |

| • Previous bouts of overt HE | ||

| Yes | 51.1 ± 18.1 | |

| No | 57.6 ± 20.7 | ns |

HE: hepatic encephalopathy.

Severity of liver disease correlated with poor quality of life measured with:

- •

CLDQ (p < 0.05, CI95% = −0.392 – −0.042 for Child-Pugh classification and p < 0.01, CI95% = −0.410 – −0.061 for MELD).

- •

Physical Component of SF-36 (p < 0.001, CI95% = −0.498 – −0.173 for Child-Pugh classification and p < 0.0001, CI95% = −0.514 – −0.192 for MELD).

- •

Mental Component of SF-36 (p < 0.05, CI95% = −0.407 – −0.054 for Child-Pugh classification and p < 0.01, CI95% = −0.457 – −0.114 for MELD).

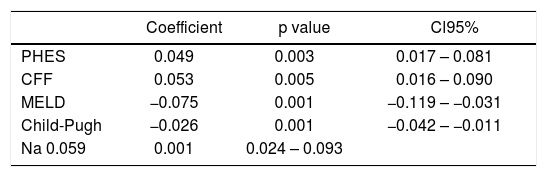

Also patients with ascites showed impaired daily functioning in all scales used (Tables 2–4). In the multivariate analysis severity of liver disease was an independent factor affecting Physical Component of SF-36 (Table 5), but not Mental Component of SF-36 and CLDQ score (data not shown).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with Physical Component of SF-36 in analyzed patients.

| Coefficient | p value | Cl95% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHES | 0.049 | 0.003 | 0.017 – 0.081 |

| CFF | 0.053 | 0.005 | 0.016 – 0.090 |

| MELD | −0.075 | 0.001 | −0.119 – −0.031 |

| Child-Pugh | −0.026 | 0.001 | −0.042 – −0.011 |

| Na 0.059 | 0.001 | 0.024 – 0.093 |

PHES: Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score. CFF: Critical Flicker Frequency. MELD: model of end-stage liver disease.

According to West Haven criteria 23 (20%) patients had symptoms of overt HE-17 (14.8%) in stage 1 and 6 (5.2%) in stage 2. Thirty two (28%) subjects fulfilled criteria for minimal HE diagnosis, thus 61 (52%) patients with cirrhosis were considered not to have HE.

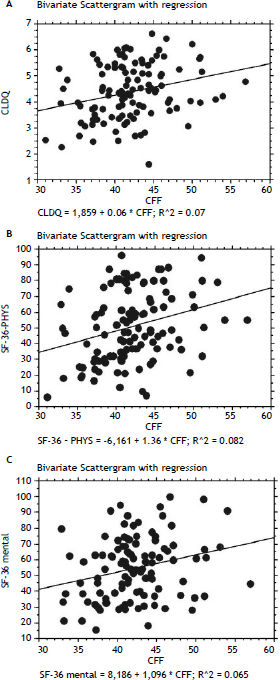

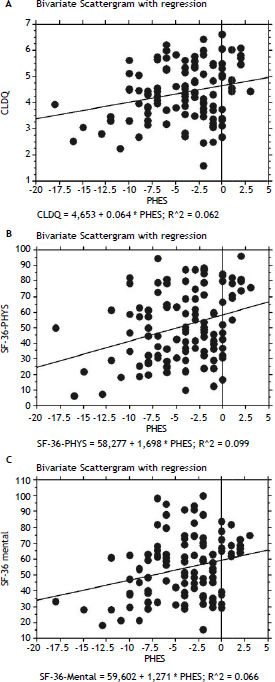

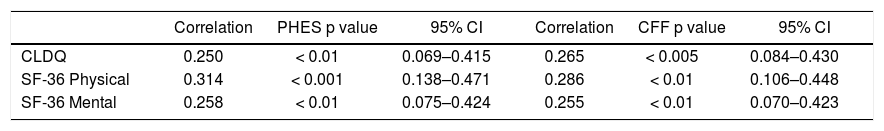

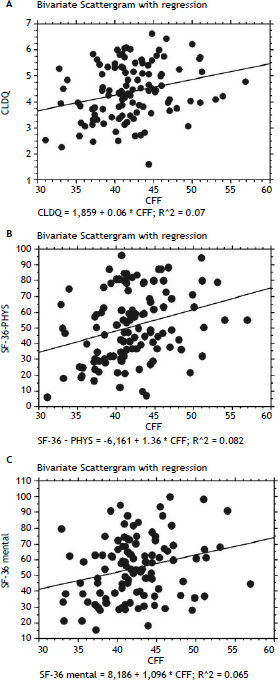

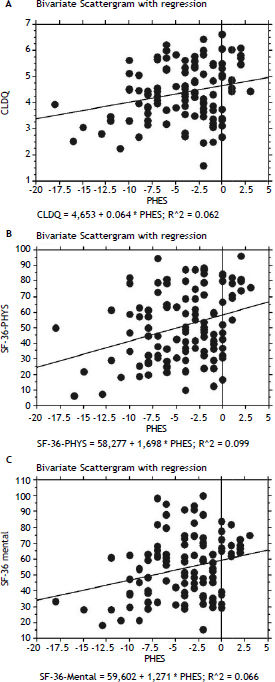

In patients with previous bouts of overt HE HR-QoL was impaired in Physical Component of SF-36 (p < 0.02) (Table 3), however the estimated West Haven stage did not influence HRQoL. Patients with minimal HE showed no difference in HRQoL, when compared to subjects without HE in all questionnaires used (Tables 2–4). Nevertheless both CFF and PHES strongly correlated with parameters of HRQoL in the univariate analysis (Figures 1 and 2, Table 6) and in the multivariate analysis were independent factors associated with poor daily functioning in regards of Physical Component of SF-36 (Table 5), but not in Mental Component of SF-36 and CLDQ Score (data not shown).

Correlation between HRQoL parameters and obtained values of neurophysiological tests.

| Correlation | PHES p value | 95% CI | Correlation | CFF p value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLDQ | 0.250 | < 0.01 | 0.069–0.415 | 0.265 | < 0.005 | 0.084–0.430 |

| SF-36 Physical | 0.314 | < 0.001 | 0.138–0.471 | 0.286 | < 0.01 | 0.106–0.448 |

| SF-36 Mental | 0.258 | < 0.01 | 0.075–0.424 | 0.255 | < 0.01 | 0.070–0.423 |

PHES: Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score. CFF: Critical Flicker Frequency. CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire.

Mean serum natremia was 136.2 mmol/l (range between 118.0 and 145.0 mmol/L). Seventy seven (66%) patients had normal serum sodium concentration (≥ 135 mmol/L) and 39 (34%) were hyponatremic (Na < 135 mmol/L). Serum natremia levels showed a significant positive correlation with HR-QoL in CLDQ (p < 0.05, CI95% = 0.015–0.371) and both summary scores of SF-36 (p < 0.001, CI95% = 0.154–0.485 for Physical Component and p < 0.05, CI95% = 0.010–0.371 for Mental Component). Patients with normal serum natremia (Na ≥ 135 mmol/L) had a significantly better HRQoL when compared to hyponatremic patients (Na < 135 mmol/L) on CLDQ (p < 0.01) and Physical Component of SF-36 (p < 0.002) (Tables 2–4).

In the multivariate analysis serum natremia was an independent factor impaired HRQoL in Physical Component of SF-36 (Table 5), but not in Mental Component of SF-36 and CLDQ Score (data not shown).

Serum kalemiaMean serum kalemia was 4.3 mmol/L (range between 2.6 and 6.2 mmol/L). Ninty two (79.3%) subject had normal serum kalemia (K ≥ 3.5 and ≤ 5.0 mmol/L), 17 (14.7%) - had hyperkalemia (K > 5.0 mmol/L) and 7 (6.0%) - hypokalemia (K < 3.5 mmol/L).

Serum kalemia showed correlation with neither quality of life (Tables 2–4), HE nor severity of the disease.

DiscussionIn this prospective project we applied two different HRQoL questionnaires (generic and specific for chronic liver diseases) to assess the influence of several cirrhosis-related complications on life’s quality in patients with liver cirrhosis. We found a significant correlation, both in univariate and multivariate analysis between serum natremia and HR-QoL. Literature data on the influence of natremia on HRQoL are limited. In a study published in an abstract form Ginès, et al. showed the negative impact of hyponatremia on HRQoL measured with SF-36.12 More recently Sola, et al., in a large group of patients with cirrhosis and ascites investigated several factors related to HRQoL, again measured with SF-36. They found that low serum sodium concentration is a major factor affecting daily functioning in these patients.13 Our study supports Sola, et al. observations. We found that reduced serum sodium concentration, but > 130 mmoL/L is an important negative predictor of quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Hyponatremia in patients with liver cirrhosis was historically defined as serum sodium concentrations below 130 mmol/L.31 However the current and widely accepted reference values for serum sodium are 135– 145 mmol/L. Thus patients with liver cirrhosis and serum sodium between 130 and 134 mmol/L should be considered as hyponatremic9 and they may present clinical consequences of hyponatremia like patients with serum sodium below 130 mmol/L.32

Serum kalemia has not yet been studied in the context of HRQoL in patients with cirrhosis. Recent, multicentre study showed that pre-transplant values of potassium not only above 5 mmol/L but also still remaining within a normal range (4.5-5.0 mmol/L) are negative predictors of survival in liver transplant recipients.11 We saw no relationship between serum potassium and analyzed factors emphasizing a significantly more important role of serum sodium in the setting of chronic liver disease.

Another clinically important observation of our study is that minimal HE did not impair HRQoL in analyzed patients. This finding confirms our previous observation,15,33 which is opposite to other studies.14,34

However neuropsychological tools like PHES and CFF, both used in our study for diagnosis of minimal HE, correlated with HRQoL parameters in whole study group (i.e. in patients without and with HE -minimal or overt). Both methods are sensitive and objective in detecting alteration of neuropsychological performance in patients with minimal and low grade overt HE. PHES is a psychometric battery recently recommended for detection of minimal HE.22,23,35 It provides the sensitive and valid evaluation of attention, visuo-spatial orientation, visual construction and motor skills i.e. neurocognitive function, that are altered very early in course of natural history of HE.36 CFF has been proven to detect a broad spectrum of neurophysiological alterations typical for early stages of HE, ranging from visual signal processing in retina (measure of retinal gliopathy) to cortical function and vigilance (general arousal).29

In contrast to neuropsychological tools, we found that West Haven criteria in patients with overt HE did not correspond with HRQoL. This novel observation can be explained by the huge variability of neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in the course of HE. West Haven classification (based on mental status changes) may remain subjective and not sensitive enough to detect subtle cognitive impairment seen in low-grade HE.37

Therefore our data also support the usefulness of neurophysiological tools in the evaluation of clinical relevance of low grade HE. If our findings are confirmed by other studies the role of West Haven classification in the assessment of HRQoL in an early HE may be questioned.

ConclusionIn this prospective study on a cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis we found that serum natremia along with indices of the severity of liver disease exerts a significant effect on patients’ HRQoL.

Abbreviations- •

CFF: critical flicker frequency.

- •

CLDQ: Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire.

- •

HE: hepatic encephalopathy.

- •

HRQoL: health-related quality of life.

- •

MELD: model of end-stage liver disease.

- •

PHES: Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score.

- •

SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

The authors declare no conflict of interest and that there is no pertinent financial arrangement.