Introduction. Liver disease related to chronic viral hepatitis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in renal transplant patients. There is no agreement upon the influence of chronic hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infection in patient and graft survival.

Aims. The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of HBV and HCV on patient and graft short and long term survival, in the patients transplanted at our institution.

Materials and methods. We evaluated the influence of antiHCV and HBsAg status (positive vs. negative); sex; age (> 49 years vs. < 49 years at transplantation); time on dialysis (> 3 vs. < 3 years); acute rejection; kind of graft (deceased vs. living donor, and kidney versus kidney and pancreas); number of transplantations; use of induction immunosuppression; and maintenance immunosuppression treatment (comparing the traditional triple therapy containing azathioprine, cyclosporine and prednisone vs. newer regimens which include tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, etc) on the survival, long term and within the first month of transplantation, of the graft and the patients transplanted in our Institution between January 1991 and August 2009.

Results. We included 542 patients, 60% males’ median age of 42.03 years (SD 13.06 years). 180 patients (33%) were antiHCV positive and 23 (4%) were HBsAg positive. AntiHCV positive, traditional triple therapy and acute rejection were associated with diminished graft survival. Older age, antiHCV positive, HBsAg positive, deceased donor, kidney-pancreas transplantation and traditional triple therapy were associated with diminished patient survival. Traditional triple therapy was associated with diminished one month graft survival; and older age and antiHCV positive were associated with diminished one month patient survival.

Conclusion. In our experience, antiHCV positive status was associated with diminished long term patient and graft survival, and diminished six month graft survival; and HBsAg positive was associated with diminished patient survival.

Liver disease related to chronic viral hepatitis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in renal transplant patients. Prevalence of hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infection in hemodialysis patients is higher than in the general population, and it varies between 1.5 to 50% depending on the world region.1–4 Fortunately in the last few years, rates of HCV and HBV seroconversion are being reduced due to HBV vaccination, use of recombinant erythropoie-tin instead of transfusions, periodic HCV testing, and use of infection control measures and routine hemodialysis unit precautions.5 Although numerous studies have been published, there is no agreement upon the influence of HBV and HCV in patient and graft survival. Some showed a reduced patient and graft survival and others did not. Also there is no agreement on the definition of short and long term. For some authors short term refers to a period between two and five years after transplantation. We refer to short term as the first six month after transplantation, a period of time characterized by profound immunosuppression, frequent episodes of acute rejection, and other events that might be influenced by chronic viral infections with immunomodulatory effects.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of HBV and HCV on patient and graft short and long term survival, in the patients transplanted at our institution.

Materials and MethodsThe clinical records of the 542 renal transplants performed at CEMIC in adult patients between January 1st 1991 and December 31st 2008 were systematically reviewed. All the information gathered up to August 31st 2009 was included in the analysis. The variables considered were: long term graft survival: the period (in years) elapsed between renal transplantation up to the return to dialysis or to the end of the evaluation; long term patient survival: the time (in years) elapsed between renal transplantation up to the patient’s death with a functioning graft, or up to the end of the evaluation; one month graft survival: time between renal transplantation up to the return to dialysis or up to the first month of transplantation; one month patient survival: time elapsed between renal transplantation up to the patient’s death with a functioning graft, or up to the first month of transplantation; six month graft survival: time between renal transplantation up to the return to dialysis or up to six month of transplantation; and six month patient survival: time elapsed between renal transplantation up to the patient’s death with a functioning graft, or up to six month of transplantation.

We evaluated the influence of antiHCV and HB-sAg status (positive vs. negative); sex; age (> 49 years vs. < 49 years at transplantation); time on dialysis (> 3 vs. < 3 years); acute rejection; kind of graft (deceased vs. living donor, and kidney versus kidney and pancreas); number of transplantations; use of induction immunosuppression (lymphocyte depleting agents, IL2 receptor blockers, or both) vs. not using it; and maintenance immunosuppression treatment (comparing the traditional triple therapy containing azathioprine, cyclosporine and prednisone vs. newer regimens which include tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, etc.) on the survival, long term and within the first month of transplantation.

All these variables were subjected to a univariate and multivariate data analysis, using the Cox proportional hazard model and expressed with the hazard ratio (HR) associated with patient survival and graft survival and their corresponding 957 confidence intervals (CI) and p values. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For comparisons between categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. Cumulative patient and graft survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan Meier method and the comparisons were performed using the log rank method. For statistical analysis STATA® software, statistics data analysis version 7.0 (Stata Corporation, Tx., USA), was used.

ResultsWe evaluated all 542 adult recipients transplanted during the study period. All were Caucasian, 60% were men, the mean age at the time of the evaluation was 42.03 years (SD: 13.03 years), 180 (33%) were antiHCV positive and 23 (4%) were HB-sAg positive. The mean time of follow up was 6.4 years (SD: 4.96 years, range 0.01-18.02 years). Demographics characteristics comparing antiHCV positive, HBsAg positive and negative patients are shown in table 1.

Population demographic characteristics (542 patients).

| Variable | HCV positive patients (%) | HCV negative patients | HBsAg positive patients (%) | HBsAg negative patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | 77 | 4 | 96 |

| 36/64 | 42/58 | 9/92# | 42/58# |

| 58# | 41# | 70# | 40# |

| 61# | 71# | 65 | 68 |

| 75# | 64# | 69 | 69 |

| 78# | 94# | 91 | 89 |

| 41# | 31# | 26 | 35 |

# Denotes differences between patients being statistically significant (P < 0.05).

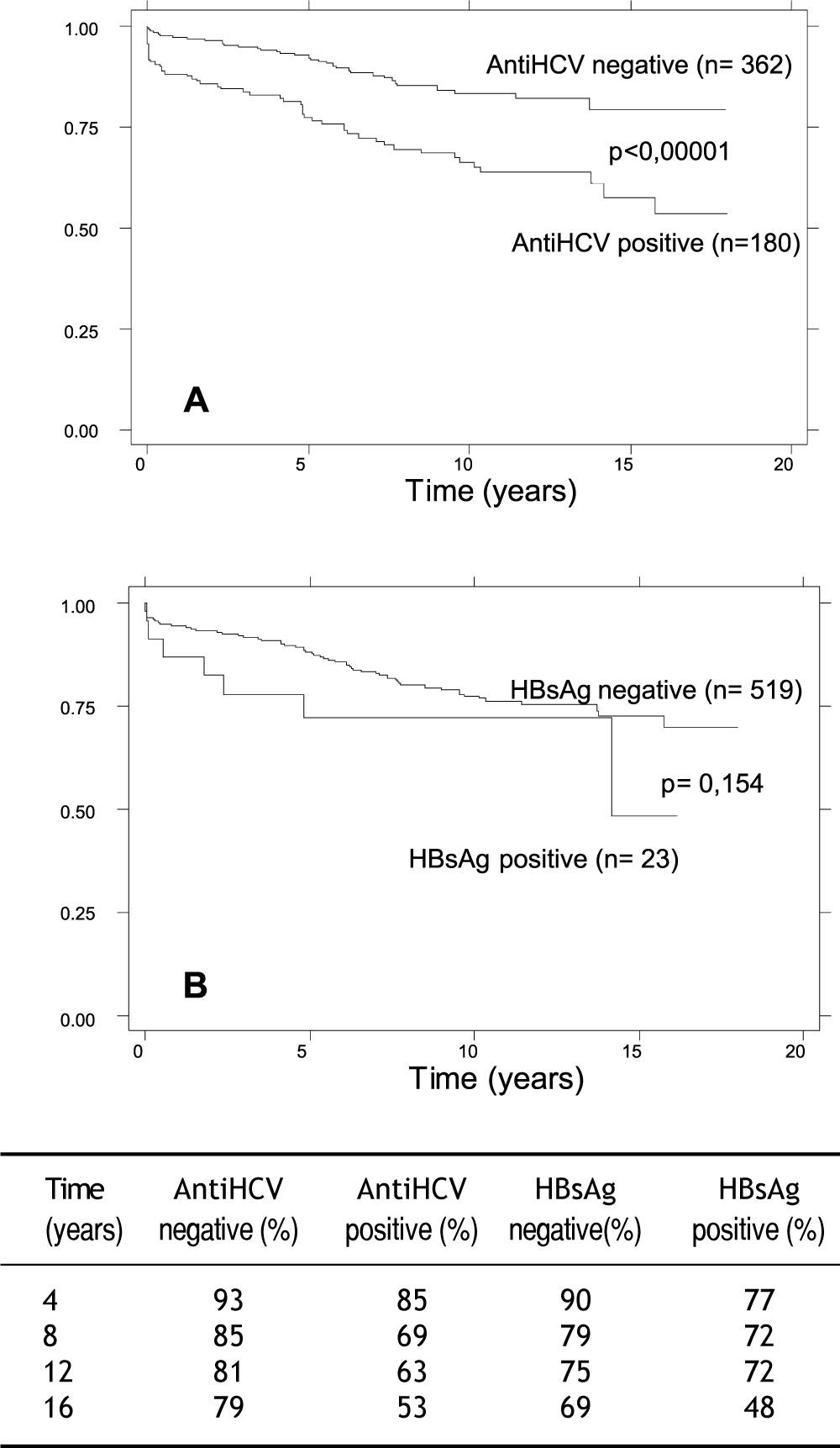

At the time of evaluation overall graft survival was 83% (448/542 patients). It was reduced in HCV positive patients: it was 70% (127/180 patients) vs. 89% (323/362 patients) in antiHCV negative patients (p < 0.001). There was no difference between HBsAg positive and negative patients: it was 69% (16/23 patients) vs. 83% (434/519 patients) (p = 0.079). In the multivariate analysis variables associated with reduced long term graft survival were antiHCV positive status, acute rejection and traditional immunosuppressive triple therapy (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis: Long term graft and patient survival.

| Outcome | Variable | HR | P value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft survival | AntiHCV positive | 2.06 | 0.001 | 1.36-3.13 |

| Acute rejection | 2.04 | 0.001 | 1.30-3.06 | |

| Immunosuppressive triple therapy | 5.67 | <0.001 | 3.27-9.84 | |

| Patient survival | Age > 49 years | 3.12 | <0.001 | 1.97-4.93 |

| AntiHCV positive | 1.64 | 0.027 | 1.05-2.55 | |

| HBsAg positive | 2.01 | 0.049 | 1.02-4.06 | |

| Cadaveric donor | 2.15 | 0.021 | 1.13-4.08 | |

| Pancreas transplantation | 5.05 | < 0.001 | 2.28-4.08 | |

| Immunosuppressive triple therapy | 1.66 | 0.021 | 1.08-2.57 |

HR: hazard risk. CI: confidence interval.

At the time of evaluation overall patient survival was 82% (448/542 patients). It was reduced in HCV positive patients: it was 74% (134/180 patients) vs. 86% (314/362 patients) in antiHCV negative patients (p < 0.001). It was also reduced in HBsAg positive patients: it was 60% (14/23 patients) vs. 83% (434/519 patients) in HBsAg negative patients (p = 0.005). Variables associated with reduced long term patient survival in the multivariate analysis are shown in table 2.

Estimated cumulative survival at 16 years showed that, antiHCV positive renal transplant population had a diminished patient and graft survival, and HBsAg positive population had a diminished patient survival compared with the rest of the populations (Figures 1 and 2).

At the end of the study, 97 patients (18%) were dead. 47% died due to infections, 25% due to cardiovascular diseases, 17% due to cancer and the remaining 11% due to other causes. HBsAg positive patients have a higher risk of cancer (44 vs. 15%, p = 0.002). Three patients’ deaths were related to liver failure (2 antiHCV and 1 HBsAg positive) and five to hepatocellular carcinoma (2 antiHCV and 3 HBsAg positive).

After one month of transplantation overall graft survival was 94% (513/542 patients). It was 91% in HCV positive patients (164/180 patients) vs. 93% (349/362 patients) in antiHCV negative patients (p < 0.010). There was no difference between HBsAg positive and negative patients: it was 95% (22/ 23 patients) vs. 94% (491/519 patients) respectively (p = 0.827). Variables associated with reduced one month graft survival in the multivariate analysis are shown in table 3.

Multivariate analysis: one and six month graft survival.

| Outcome | Variable | HR | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One month graft survival | AntiHCV positive | 2.10 | 0.053 | 0.99-4.45 |

| Immunosuppressive triple therapy | 2.30 | 0.037 | 1.05-5.06 | |

| Six month graft survival | Age > 49 years | 2.19 | 0.029 | 1.05-2.83 |

| AntiHCV positive | 2.65 | 0.008 | 1.19-3.23 | |

| Cadaveric donor | 1.90 | 0.058 | 0.97-3.56 | |

| Immunosuppressive triple therapy | 3.11 | 0.002 | 1.34-3.73 |

HR: Hazard risk. CI: Confidence interval.

After one month of transplantation overall patient survival was 97% (528/542 patients). There was also difference between antiHCV positive, HBsAg positive and negative patients. None of the variables were associated with reduced one month patient survival.

After six month of transplantation overall graft survival was 87% (475/542 patients). It was 80% in HCV positive patients (144/180 patients) vs. 91% (331/362 patients) in antiHCV negative patients (p < 0.001). There was no difference between HBsAg positive and negative patients: it was 86% (20/23 patients) vs. 87% (475/519 patients) respectively (p = 0.919). Variables associated with reduced six month graft survival in the multivariate analysis are shown in table 3.

After six month of transplantation overall patient survival was 96% (502/542 patients). It was reduced in HCV positive patients, 89% (161/180 patients) vs. 92% (341/362 patients) in antiHCV negative patients (p = 0.046). There was no difference between HBsAg positive and negative patients: it was 95% (22/23 patients) vs. 92% (480/519 patients) respectively (p = 0.570). In the multivariate analysis variables associated with reduced six month patient survival were age older than 49 years (HR: 1.93, p = 0.042, CI95% 1.02-3.63), and traditional immunosuppressive triple therapy (HR: 2.40, p = 0.009, CI95% 1.24-4.64). HCV positive status was associated with reduced survival in the univariate analysis (HR: 1.94, p = 0.035, CI957 1.04-3.62) but not in the multivariate analysis (HR: 1.48, p = 0.225, CI957 0.78-2.83).

DiscussionWe have previously reported the results on the outcomes in our population of renal transplant patients with chronic viral hepatitis.6,7 A longer follow up revealed that in our population, antiHCV and HBsAg positive status are associated with an increased risk of graft lost and death. Even though these patients were more frequently transplanted with deceased donors, transplanted more than once, received conventional immunosuppression, and presented more frequently episodes of rejection, chronic viral hepatitis were independently associated with a worst outcome, regardless of the baseline characteristics of the population.

Several studies demonstrated that patients with HCV infection after renal transplantation exhibited a similar survival in the short term as compared to no-ninfected renal transplant patients. Authors defined “short term” as a period of time between two and five years after transplantation, which differs from our six month period.8–14 This might be different for HBV. Even though there is less information than in the HCV population, HBV renal transplant patients seems to have reduce short term survival.14 However, in the long term, the situation is different in most of the series, showing that HCV-positive patients have a significantly lower survival than HCV-negative pa-tients.15–25 Reduced long term patient survival has also demonstrated in kidney recipients infected with HBV virus.18,21,24,26–28 Although there is enough evidence confirming reduced patient survival in this population as previously mentioned, there are still some reports showing that long term survival is not reduced in chronic viral hepatitis.29–31 There are multiple explanations for the differences in the results of the published studies: a different time of follow up, usually less than 10 years, for diseases evolving over decades; a small number of patients from a single center; confounding factors, e.g., differences in immuno-suppressive protocols; and possibly, the most important factor, the difficulty in the interpretation of the data is that patients have usually not been adequately studied in relation to the severity of their liver disease. Also, some groups do not include patients with viral hepatitis in their transplant list and patients with severe comorbidities are generally not transplanted, thus generating a selection of patients which makes comparisons very difficult.

As in the case of patient survival, HCV infection does not appears to influence short term graft survival.8–13 However, in most of the recent studies with longer follow up, patients with HCV infection exhibited lower graft survival compared with HCV-negative patients.9,18,20–25,30 Overall graft survival is not affected in the short term, but it is reduced in patients infected with HBV virus.24,30,32

Our results are similar to those previously cited. We found that long term patient and graft survival is reduced in HBV and HCV infected renal recipients; and that HCV independently predicts patient and graft survival, and that HBV independently predicts patient survival in multivariate analysis. But we were able to demonstrate that chronic hepatitis C viral infection affects very short term outcomes in renal transplantation. It is associated with reduced six month graft survival (HR 2.65, p = 0.008, CI95% 1.19-3.23) and showed a trend towards reduced graft survival within the first month after transplantation (HR 2.10, p = 0.053, CI95% 0.99-4.45). It has no effect on patient survival within the first month, but showed reduced six month patient survival after transplantation albeit it is not an independent predictor of outcome.

Although long-term survival rates are lower in HCV-positive compared with HCV-negative graft recipients, kidney transplantation still remains the best option for HCV-positive patients with end-stage renal disease, since survival, even short-term, would be substantially lower on the waiting list.33–38 Pre-transplant assessment by a hepatologist is essential in this special group of chronic liver disease. Liver biopsy must be performed before transplantation to adequately select candidates suitable for renal transplantation; to evaluate initiating treatment before renal transplantation in the case of HCV, given that Peg-interferon is contraindicated after transplant; and for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, to select candidates suitable for liver-kidney transplantation.16,39 Chronic HCV positive patients’ candidates for transplantation should receive treatment while on dialysis as it is effective (40-90% sustained virological response according to different series) and response is maintained after transplantation.40–46 In patients with chronic HBV infection, treatment must be initiated before and maintained after transplantation, as newer nucleosid(t)e analogs are effective in controlling infection in immunocompromised hosts and poses no risk for the renal allograft.47–49

In our experience, antiHCV positive status was associated with diminished long term patient and graft survival, with diminished short term graft survival and showed a trend towards reduced graft survival within the first month after transplantation; and HBsAg positive was associated with diminished patient survival.

AcknowledgementsWe are indebted to Dr. Hugo Krupitzky for his help with the statistical analysis, and to Valeria Iabichella for her expert secretarial assistance.

Financial DisclosureNone.