Introduction. Steatotic livers have been associated with greater risk of allograft dysfunction in liver transplantation. Our aim was to determinate the prevalence of steatosis in grafts from deceased donors in Chile and to assess the utility of a protocol-bench biopsy as an outcome predictor of steatotic grafts in our transplant program.

Material and methods. We prospectively performed protocol-bench graft biopsies from March 2004 to January 2009. Biopsies were analyzed and classified by two independent pathologists. Steatosis severity was graded as normal from absent to < 6%; grade 1: 6-33%; grade 2: > 33-66% and grade 3: > 66%.

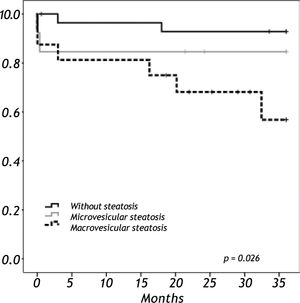

Results. We analyzed 58 liver grafts from deceased donors. Twenty-nine grafts (50%) were steatotic; 9 of them (16%) with grade 3. Donor age (p < 0.001) and BMI over 25 kg/m2 (p = 0.012) were significantly associated with the presence of steatosis. There were two primary non-functions (PNF); both in a grade 3 steatotic graft. The 3-year overall survival was lower among recipients with macrovesicular steatotic graft (57%) than recipients with microvesicular (85%) or non-steatotic grafts (95%) (p = 0.026).

Conclusion. Macro-vesicular steatosis was associated with a poor outcome in this series. A protocol bench-biopsy would be useful to identify these grafts.

The use of steatotic livers for liver transplantation (LT) has been associated with a greater risk of complications due to higher rates of preservation injury and allograft dysfunction.1-2 However, the growing number of patients on waiting lists for LT and the shortage of organ donors have forced many centers to accept extended criteria for graft selection, moving the limit of acceptance for grafting beyond the classic 33% of liver steatosis.3 Since nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become a common condition in the general population,4reaching figures of up to 30% of prevalence, the decision as to whether to use a steatotic graft is a common difficulty for the liver transplant team. This is particularly true in countries with a high prevalence of subjects with Hispanic genetic background, since the prevalence of NAFLD is higher among these subjects.5

Although a protocol-bench biopsy is the best way to assess the degree of steatosis and the presence of necroinflammatory changes in liver grafts, this procedure is not routinely used in LT.6 The aim of the present study was to determinate the prevalence of steatosis in grafts from deceased donors in Chile and to assess the utility of a protocol-bench biopsy as an outcome predictor when using steatotic and non-steatotic grafts for LT.

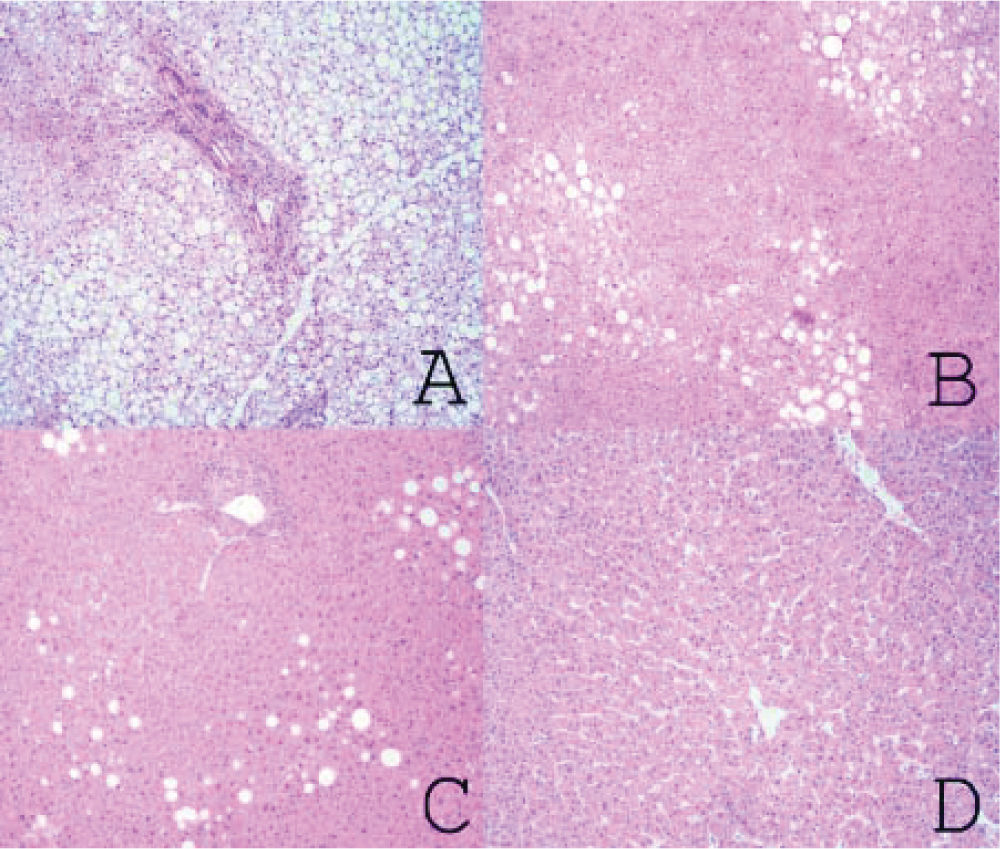

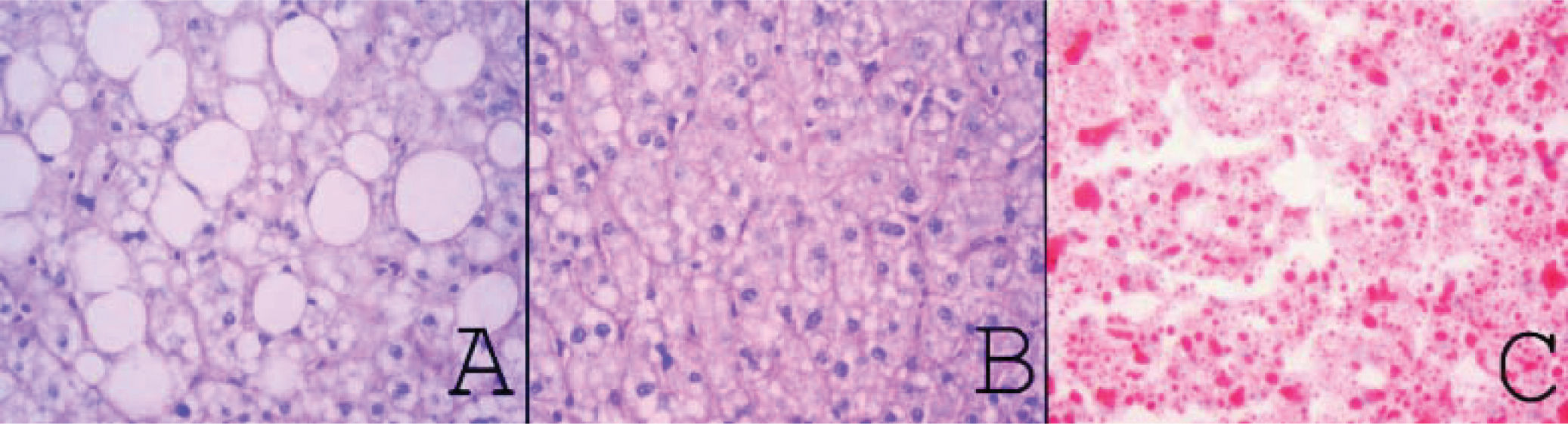

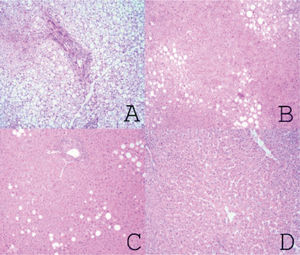

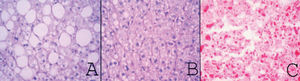

Material and MethodsFrom March 2004 to January 2009, we prospectively performed a protocol-bench graft biopsy for every LT performed in our institution. Specimens obtained on bench were fixed in buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, and stained with hematoxilineosin. All liver biopsies were reassessed by two independent experienced pathologists with no knowledge of the original pathology report. Degree of steatosis was assessed according to Kleiner7 and Brunt.8 Macro-and microsteatosis were evaluated semi-quantitatively. Severe steatosis (grade 3) was defined as the presence of fat droplets in more than 66% of hepatocytes in the graft biopsy; moderate (grade 2) and mild (grade 1) steatosis were defined as the presence of fat droplets between 34-66% and 6-33% respectively, following current recommendations8 (Figures 1A-1C). The presence of less than 6% of steatosis was considered normal (Figure 1D). Macrovesicular/microvesicular steatosis biopsies were classified as predominantly macrovesicular or predominantly microvesicular (Figure 2A-2C). Specimens, predominantly microvesicular on hematoxilin-eosin were also stained with the PAS/PAS-diastase method. One case with steatohepatitis was not considered in this study because this graft was discharged. No fibrosis other than grades 0 or 1A was found.

A.Severe steatosis: small, medium and large fat vacuoles in over 66% of hepatocytes (hematoxylin and eosin x40). B. Moderate steatosis: small, medium and large fat vacuoles in approximately 60% of hepatocytes (Hematoxylin and eosin x40). C. Mild steatosis: medium and large fat vacuoles in approximately 10% of hepatocytes (hematoxylin and eosin x40). D. Normal (non-steatotic) liver. No cytoplasmic fat vacuoles are seen (hematoxylin and eosin x40).

A.Macrovesicular steatosis: one or a few well-demarcated fat vacuoles displace the nucleus to the edge of the cell (PAS-diastase, original magnification x400). B. Microvesicular steatosis: multiple, well-demarcated cytoplasmic microvacuoles surround the nucleus without altering their location (PAS-diastase, original magnification x400). C. microvesicular steatosis: frozen section stained for lipid (Oil-Red-O, original magnification 400x).

The outcomes of patients who received steatotic grafts were compared to those of a group of patients grafted with non-steatotic livers. Surgeons did not have detailed pathology reports before at the time of transplantation. Thus, decisions about graft implantation were based mainly on macroscopic aspects of the liver and the urgency of LT indications.

Donor dataOrgan procurement was performed either with aortic and portal perfusion, or only aortic perfusion, depending on the surgeon's preference. Preservation solutions were either Histidine-Tryptophan-Ketoglutarate (CustodiolTM) or University of Wisconsin (ViaspanTM).

In addition to steatosis, the following donor or graft data were recorded: occurrence of cardiac arrest, donor age (≥ 60 years), high vasoactive drug requirement (2 or more drugs), length of stay in intensive care unit (more than 4 days) and cold ischemic time (more than 10 h). The donor's cause of death was also analyzed. Donor obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Recipient dataDemographic data, indication of transplantation (Urgent/Elective), and clinical status assessed by the Child-Pugh and MELD scores of all recipients were recorded in the local database.

Postoperative outcomeLiver allograft function was evaluated clinically and through the use of selected biochemical parameters. Liver function tests were measured on arrival at the ICU. Initial poor graft function (IPGF) was defined as an increase in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) > 1,500 UI/L and prothrombin time exceeding 20 sec during the first postoperative week. Primary non-function (PNF) was defined as poor function of the allograft culminating in either the death of the recipient or the need for re-transplantation, in the absence of any vascular complication.

Statistical analysisFor survival calculations we included the variables of cold ischemic time, preservation solution, warm ischemic time, sex, BMI, in a multivariate analysis. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparison among groups was carried out using the logrank test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test for independent samples. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be significant. Calculations were done with the SPSS statistical software package (version 19.0).

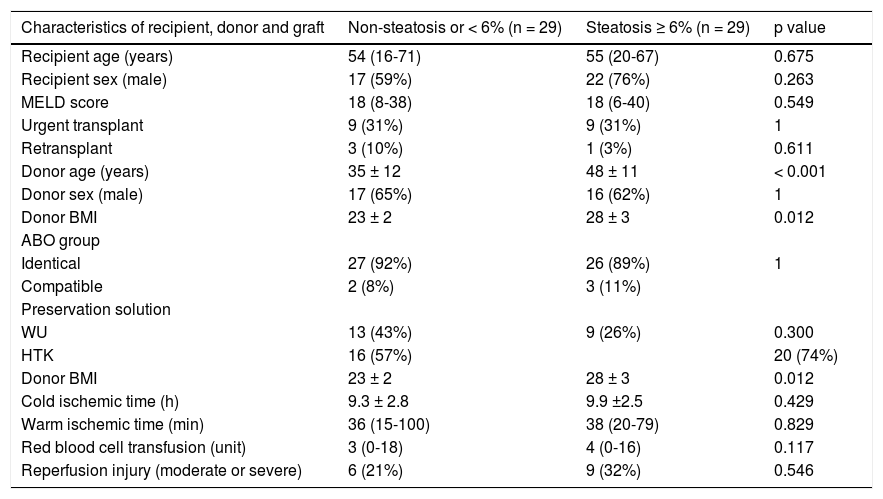

ResultsFifty-nine liver graft biopsies were obtained and analyzed during the study period. In one case the graft was discharged, because a call warning of pathologist about a severe steatosis and steatohepatitis observed. The surgical team decided to not proceed with the transplant procedure. Then, the results were analyzed on 58 grafts biopsied and implanted. There were no clinical differences among most demographic characteristics of recipients and donors between steatotic and non-steatotic grafts (Table 1). The only 2 characteristic investigated associated with steatotic graft were BMI (23 vs. 28 kg/m2, p = 0.011) and donor age (35 vs. 48 years, p < 0.001). BMI among over 25 kg/m2 donors was significantly associated with the presence of steatosis (p = 0.012). Only five patients with steatosis had a BMI ≥ 30 m/kg2.

Demographic characteristics of cases.

| Characteristics of recipient, donor and graft | Non-steatosis or < 6% (n = 29) | Steatosis ≥ 6% (n = 29) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient age (years) | 54 (16-71) | 55 (20-67) | 0.675 |

| Recipient sex (male) | 17 (59%) | 22 (76%) | 0.263 |

| MELD score | 18 (8-38) | 18 (6-40) | 0.549 |

| Urgent transplant | 9 (31%) | 9 (31%) | 1 |

| Retransplant | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 0.611 |

| Donor age (years) | 35 ± 12 | 48 ± 11 | < 0.001 |

| Donor sex (male) | 17 (65%) | 16 (62%) | 1 |

| Donor BMI | 23 ± 2 | 28 ± 3 | 0.012 |

| ABO group | |||

| Identical | 27 (92%) | 26 (89%) | 1 |

| Compatible | 2 (8%) | 3 (11%) | |

| Preservation solution | |||

| WU | 13 (43%) | 9 (26%) | 0.300 |

| HTK | 16 (57%) | 20 (74%) | |

| Donor BMI | 23 ± 2 | 28 ± 3 | 0.012 |

| Cold ischemic time (h) | 9.3 ± 2.8 | 9.9 ±2.5 | 0.429 |

| Warm ischemic time (min) | 36 (15-100) | 38 (20-79) | 0.829 |

| Red blood cell transfusion (unit) | 3 (0-18) | 4 (0-16) | 0.117 |

| Reperfusion injury (moderate or severe) | 6 (21%) | 9 (32%) | 0.546 |

MELD: model for end-stage liver disease. BMI: body mass index. WU: Wisconsin University. HTK: histidine-trypthopan-ketoglutarate. Values expressed in means ± standard deviation or in medians (ranges) according to their distribution. P value calculated using chi square or Fisher test for categorical variable and t-test or Mann-Whitney test according to their distribution for continuous variable.

Seventy-two percent of donors with steatotic livers were over 40 years of age vs. 38% of donors without steatosis (OR 4.3, IC 95% 1.4-12.9, p = 0.008).

Twenty-nine (50%) of the 58 liver grafts analyzed were steatotic livers; 13 (22%) with steatosis grade 1; 7 (12%) with steatosis grade 2 and 9 (16%) with steatosis grade 3. The majority of the donors were male [37 (64%)]. The mean donor age was 41.4 ± 14.

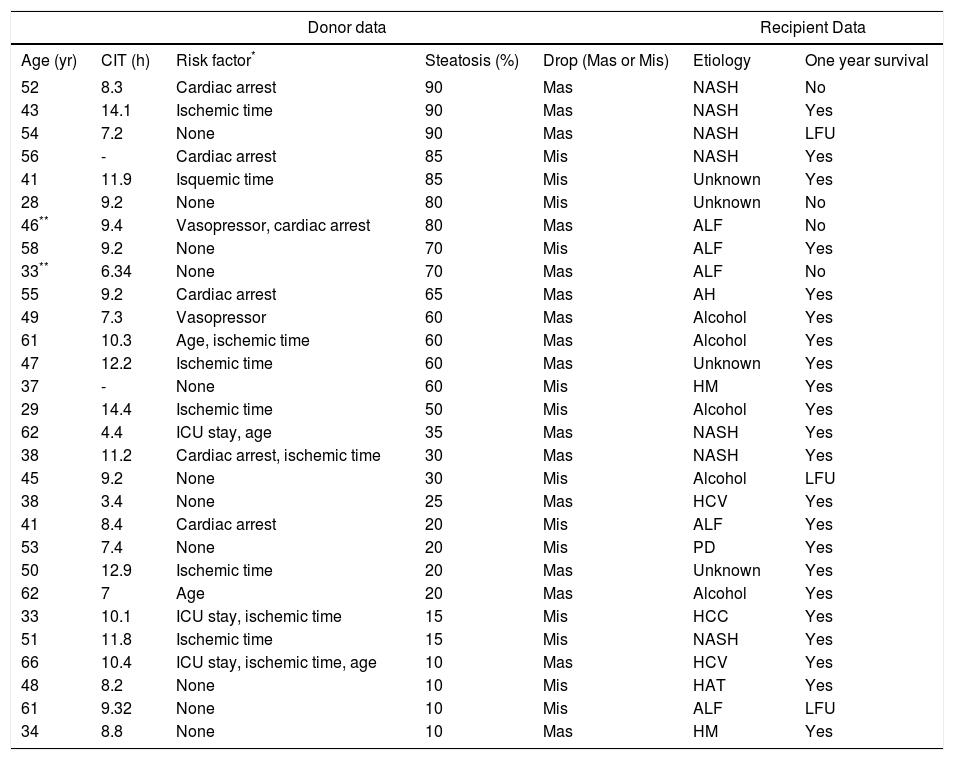

Fifteen (26%) grafts had macrosteatosis, which was mainly associated with grade 3 steatotic livers (p = 0.034). Table 2 lists donor features and recipient outcomes for each graft with steatosis. Grafting of a steatotic liver was significantly associated with an increase in serum levels of aminotranferases greater than 1,500 U/mL (p = 0.0001) and was not associated with a rise of total bilirubin, or with a decrease in prothrombin time.

Donor and recipient features of each graft with steatosis.

| Donor data | Recipient Data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | CIT (h) | Risk factor* | Steatosis (%) | Drop (Mas or Mis) | Etiology | One year survival |

| 52 | 8.3 | Cardiac arrest | 90 | Mas | NASH | No |

| 43 | 14.1 | Ischemic time | 90 | Mas | NASH | Yes |

| 54 | 7.2 | None | 90 | Mas | NASH | LFU |

| 56 | - | Cardiac arrest | 85 | Mis | NASH | Yes |

| 41 | 11.9 | Isquemic time | 85 | Mis | Unknown | Yes |

| 28 | 9.2 | None | 80 | Mis | Unknown | No |

| 46** | 9.4 | Vasopressor, cardiac arrest | 80 | Mas | ALF | No |

| 58 | 9.2 | None | 70 | Mis | ALF | Yes |

| 33** | 6.34 | None | 70 | Mas | ALF | No |

| 55 | 9.2 | Cardiac arrest | 65 | Mas | AH | Yes |

| 49 | 7.3 | Vasopressor | 60 | Mas | Alcohol | Yes |

| 61 | 10.3 | Age, ischemic time | 60 | Mas | Alcohol | Yes |

| 47 | 12.2 | Ischemic time | 60 | Mas | Unknown | Yes |

| 37 | - | None | 60 | Mis | HM | Yes |

| 29 | 14.4 | Ischemic time | 50 | Mis | Alcohol | Yes |

| 62 | 4.4 | ICU stay, age | 35 | Mas | NASH | Yes |

| 38 | 11.2 | Cardiac arrest, ischemic time | 30 | Mas | NASH | Yes |

| 45 | 9.2 | None | 30 | Mis | Alcohol | LFU |

| 38 | 3.4 | None | 25 | Mas | HCV | Yes |

| 41 | 8.4 | Cardiac arrest | 20 | Mis | ALF | Yes |

| 53 | 7.4 | None | 20 | Mis | PD | Yes |

| 50 | 12.9 | Ischemic time | 20 | Mas | Unknown | Yes |

| 62 | 7 | Age | 20 | Mas | Alcohol | Yes |

| 33 | 10.1 | ICU stay, ischemic time | 15 | Mis | HCC | Yes |

| 51 | 11.8 | Ischemic time | 15 | Mis | NASH | Yes |

| 66 | 10.4 | ICU stay, ischemic time, age | 10 | Mas | HCV | Yes |

| 48 | 8.2 | None | 10 | Mis | HAT | Yes |

| 61 | 9.32 | None | 10 | Mis | ALF | LFU |

| 34 | 8.8 | None | 10 | Mas | HM | Yes |

Primary non-function. LFU: live at follow up. CIT: cold ischemic time. Mas: macrosteatosis. Mis: microsteatosis. ICU: intensive care unit. ALF: acute liver failure. NASH: no-alcoholic steatohepatitis. HCC: hepatocarcinoma. HCV: hepatitis C virus. AH: autoimmune hepatitis. HAT: Hepatic artery thrombosis. PD: polycystic disease. HM: hemocromatosis.

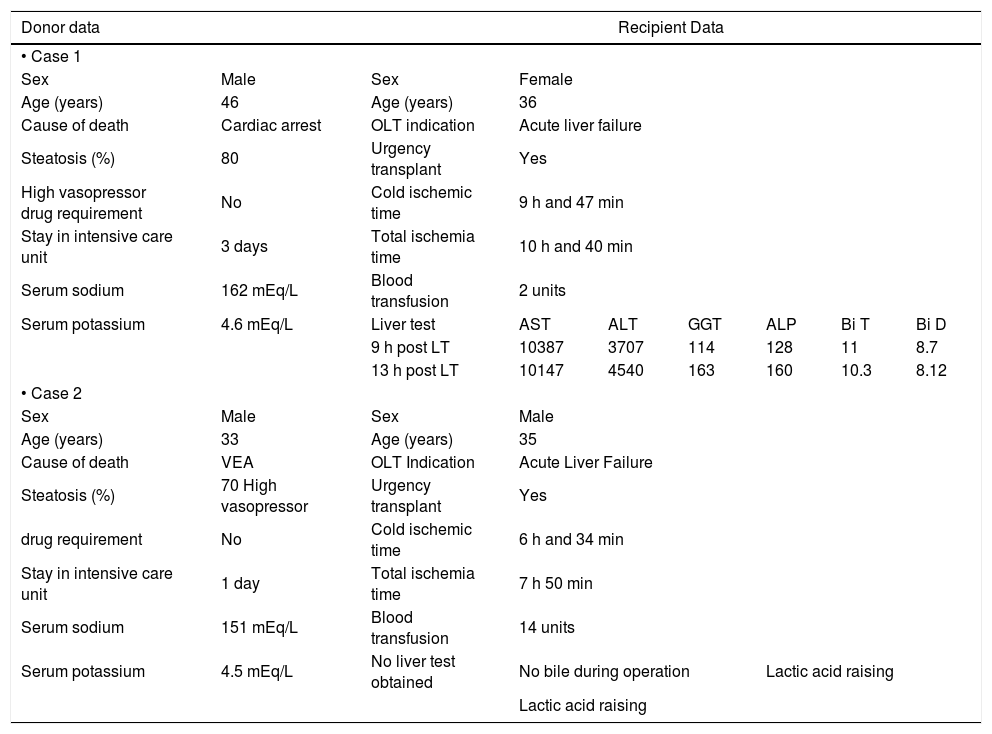

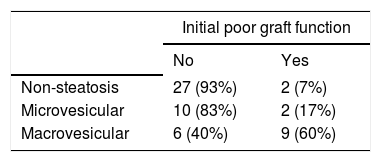

We observed two PNFs resulting in patient death. These patients were not re-transplanted due to the lack of donor availability. Both had severely (grade 3) steatotic livers; one of them 70% and the other 80% (Table 3). Another patient had an IPGF, requiring a successful re-transplantation after three months. Thirteen patients developed IPGF and eleven of them had a steatotic liver. Patients with macrovesicular steatosis had a significantly higher incidence of IPGF than patients with microvesicular steatosis: 60% vs. 17% respectively (p < 0.001, Chi-Square Test) (Table 4).

Features of PNF cases.

| Donor data | Recipient Data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Case 1 | ||||||||

| Sex | Male | Sex | Female | |||||

| Age (years) | 46 | Age (years) | 36 | |||||

| Cause of death | Cardiac arrest | OLT indication | Acute liver failure | |||||

| Steatosis (%) | 80 | Urgency transplant | Yes | |||||

| High vasopressor drug requirement | No | Cold ischemic time | 9 h and 47 min | |||||

| Stay in intensive care unit | 3 days | Total ischemia time | 10 h and 40 min | |||||

| Serum sodium | 162 mEq/L | Blood transfusion | 2 units | |||||

| Serum potassium | 4.6 mEq/L | Liver test | AST | ALT | GGT | ALP | Bi T | Bi D |

| 9 h post LT | 10387 | 3707 | 114 | 128 | 11 | 8.7 | ||

| 13 h post LT | 10147 | 4540 | 163 | 160 | 10.3 | 8.12 | ||

| • Case 2 | ||||||||

| Sex | Male | Sex | Male | |||||

| Age (years) | 33 | Age (years) | 35 | |||||

| Cause of death | VEA | OLT Indication | Acute Liver Failure | |||||

| Steatosis (%) | 70 High vasopressor | Urgency transplant | Yes | |||||

| drug requirement | No | Cold ischemic time | 6 h and 34 min | |||||

| Stay in intensive care unit | 1 day | Total ischemia time | 7 h 50 min | |||||

| Serum sodium | 151 mEq/L | Blood transfusion | 14 units | |||||

| Serum potassium | 4.5 mEq/L | No liver test obtained | No bile during operation | Lactic acid raising | ||||

| Lactic acid raising | ||||||||

OLT: orthotropic liver transplantation. mEq/L: milliequivalents of solute per liter. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. ALT: alanine transaminase. GGT: gama glutamil transpeptidase. ALP: alkaline phosphatase. Bi T: total bilirubin. Bi D: direct bilirubin. VEA: vascular encephalic arrest.

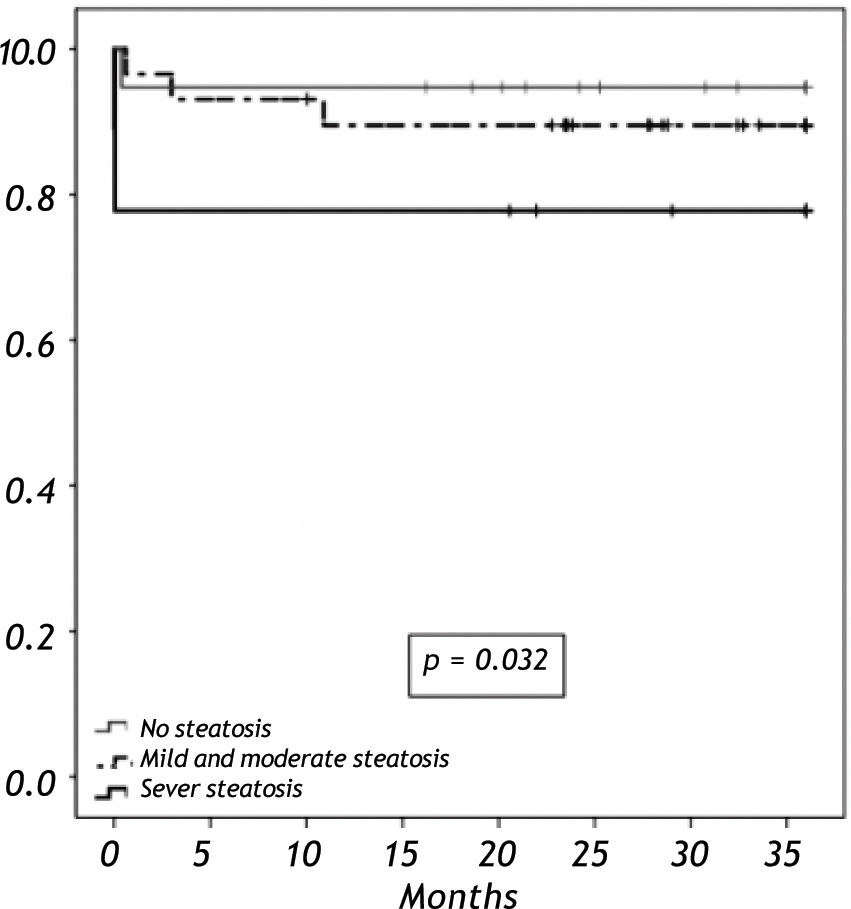

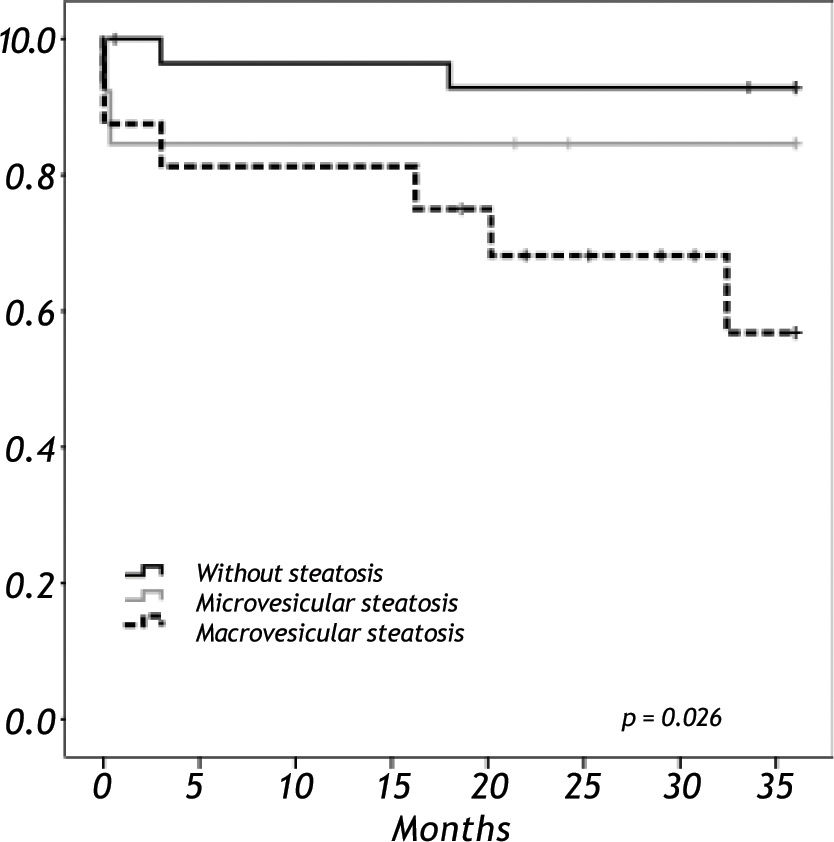

When we analyzed the overall survival with the variables of cold ischemic time, preservation solution, warm ischemic time, sex, BMI in a multivariate analysis, there was no impact in overall survival. Overall survival at five years follow-up for non-steatotic and livers with more than 66% of steatosis was 95% and 78% respectively (p = 0.032) (Figure 3). There are no differences in cold ischemic time between steatotic and non-steatotic livers (p = 0.429). Only two deaths occurred among patients who received normal liver grafts during the follow-up, with no graft failure. Causes of death were heart attack at three months and sepsis due to severe pneumonia at eleven months after LT. The 3-year overall survival was lower among recipients with macrovesicular steatotic graft (57%) than recipients with microvesicular (85%) or non-steatotic grafts (95%) (p = 0.026) (Figure 4).

The increasing need for organ grafts has forced liver transplant teams to use extended criteria grafts that do not meet optimal accepted definitions aimed at obtaining the best outcome after transplantation.9 The combination of multiple risk factors [such as donor age (> 55 years), donor hospital stay (> 5 days), hepatic steatosis, cold ischemia time (> 10 h), and warm ischemia time] seems to be additive in terms of the graft injury occurrence rate.10 Among these risk factors, steatosis is probably the most common, raising the question of whether or not to use a steatotic liver. Up to 50% of patients undergoing major liver resection11 and up to 30% among deceased organ donors had liver steatosis, according to different series.12-13 In the present study, we found an even higher frequency (50%). This disparity may be due to the different criteria to quantify and qualify liver steatosis. El-Badry, et al. showed a significant variability among experts in quantitative and qualitative assessments of the histological features of liver steatosis.13 The type of biopsy stain used also plays an important role, for example, Sudan-III or toluidine blue are more sensitive in detecting steatosis than hematoxilin-eosine.14-15 In our study we used only hematoxylin-eosin staining, so we recognize that graft steatosis may be undervalued. Other reasons for this disparity could be related to different donor selection policies, as well as ethnicity, obesity rates and predisposition to NAFLD and alcohol consumption; all factors that may determine the high prevalence of steatosis among Chilean donors.

A number of studies in the 1990s reported that transplantation with livers harboring severe steatosis almost invariably led to PNF. In a recent study McCormack, et al.9 reported a 3-year survival rate of 83% and 84% among patients receiving livers with severe steatosis (≥ 60%), as compared to those who received a normal allograft. In the present study, we observed only 2 PNF, 3.4% of the entire series. However, they occurred exclusively in the group with severe steatosis. The two patients urgently required liver replacement and the macroscopic steatotic allografts were the only grafts available in the country. Notably, in general there are few donors per inhabitant in Chile.16

We found a 7% incidence of IPGF among non-steatosic grafts vs. 37% among steatotic grafts. Within this latter group, there were no difference in grafts with steatosis ≤ 33% vs. > 33% (39% vs. 35% respectively), in contrast to other series that report higher initial poor function in moderate steatosis.17-18

Overall, the observed 3-year rates were 67% and 93% in subjects receiving liver allografts with severe steatosis (≥ 66%) and normal allografts, respectively. Our survival rate is significantly lower than that reported by McCormack, et al.,9 who found a 3-year survival rate of 83% among patients transplanted with grafts with severe steatosis. This difference may be because the MELD scores of recipients in the McCormack study were quite low (mean 12). Moreover, in our study, this subgroup of patients had a rather high mean cold ischemia time (10 ± 2 h).

Others studies have shown 12-month-survival rates of 58%19 and 25%20 among patients receiving grafts with more than 60% macroesteatosis. Our 12-month-survival rate of patients receiving grafts with more than 66% macroesteatosis was 40%, which is in accordance with the other studies.

Specifically, the presence of macrovesicular steatosis is a risk factor of a poor outcome. In our study, we found an increased risk of poor initial function and a lower 3-year-survival rate among patients receiving grafts with macrosteatosis compared to patients who received microesteatosis or non-steatotic grafts. These results are consistent with the results reported by others authors.21-22

In a study with 501 liver transplant patients, Spitzer, et al.23 showed that more than 30% macrosteatosis was an independent risk factor associated with a lower one-year graft survival rate (relative risk 1.71). We observed that grafts with > 33% of macrosteatosis had lower one year graft survival than livers with the same proportion of microsteatosis: 70% vs. 83% respectively, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

The issue of using Microvesiculars (MiS) or Macrovesiculars (MaS) fatty livers remains controversial.24 Some groups have recommended that grafts with more than 30% of macrovesicular steatosis should not be used for LT,25-26 but on the other hand, a recent study demonstrated that MiS is an independent donor factor influencing graft function, and reported a 100% primary graft non-function rate when severely steatotic grafts with MiS were used for re-transplantation.27 However, other group have suggested that livers with severe MiS can be safely used for LT.28

Our results show that using steatotic grafts was associated with a lower survival rate than the rate with normal allografts. However, we did not find significant differences in patient survival when we compare using mild, moderate or severe steatotic allografts, which very likely is related to the small number of cases in each group.

To our knowledge there is no formal recommendation to perform a liver biopsy with every donor. The present clinical practice is that livers judged to be fatty by the harvesting surgeon are evaluated with histological analysis. Ureña, et al.29 in 1998 stressed that an intraoperative donor biopsy should be performed before graft perfusion with the preservative solution, but procurement teams do not always have all the tools to perform the biopsy at the donor hospital. From our experience, it is easier to execute the graft biopsy on bench at the transplant centre than at donor facilities.

NAFLD affects up to 30% of the population and up to 80% of obese individuals in Western countries.4,30-31 Despite this, only 23% of liver transplant recipients in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) have any record of a liver donor biopsy,14 even though the majority of liver transplant programs require a graft biopsy before accepting or rejecting the graft.32

The risk factors for NAFLD include diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertriglyceridemia and sedentary life style.33 In our study, a BMI over 25 was significantly associated with graft steatosis. The other risk factor associated with steatotic liver that we found was a donor age of more than 40 years. Consequently, we believe that a donor age of over 40, donor BMI of over 25 kg/m2, and histories of diabetes mellitus and hypertriglyceridemia should be indications of the need for graft biopsy to assess the degree and type of steatosis.

In summary, fatty liver is a prevalent problem that affects the survival of transplant patients, but given the lack of donors in our country, we should not reject livers that are classified as steatotic based only on clinical appraisal in the operating room, making histological assessment necessary. In fact, in this setting, fatty livers up to 50% of steatosis can be used safely.

Abbreviations- •

LT: liver transplantation.

- •

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

- •

MaS: macrosteatosis.

- •

MiS: microsteatosis.

- •

MELD: model for end-stage liver disease.

- •

FA: fatty acid.

This work was partially supported by a grant from the Chilean National Fund for Research in Science and Technology (FONDECYT 1110455 and ACT79 to MA).

Conflict of InterestNone of the authors has conflicts of interest to disclose.