Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) with its focus on herbal use became popular worldwide. Treatment was perceived as safe, with neglect of rare adverse reactions including liver injury. To compile worldwide cases of liver injury by herbal TCM, we undertook a selective literature search in the PubMed database and searched for the items Traditional Chinese Medicine, TCM, Traditional Asian Medicine, and Traditional Oriental Medicine, also combined with the terms herbal hepatotoxicity or herb induced liver injury. The search focused primarily on English-language case reports, case series, and clinical reviews. We identified reported hepatotoxicity cases in 77 relevant publications with 57 different herbs and herbal mixtures of TCM, which were further analyzed for causality by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) scale, positive reexposure test results, or both. Causality was established for 28/57 different herbs or herbal mixtures, Bai Xian Pi, Bo He, Ci Wu Jia, Chuan Lian Zi, Da Huang, Gan Cao, Ge Gen, Ho Shou Wu, Huang Qin, Hwang Geun Cho, Ji Gu Cao, Ji Xue Cao, Jin Bu Huan, Jue Ming Zi, Jiguja, Kudzu, Ling Yang Qing Fei Keli, Lu Cha, Rhen Shen, Ma Huang, Shou Wu Pian, Shan Chi, Shen Min, Syo Saiko To, Xiao Chai Hu Tang, Yin Chen Hao, Zexie, and Zhen Chu Cao. In conclusion, this compilation of liver injury cases establishes causality for 28/57 different TCM herbs and herbal mixtures, aiding diagnosis for physicians who care for patients with liver disease possibly related to herbal TCM.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and in particular its herbal sector is popular in China1 and many countries worldwide.2–4 For most traditional herbal treatments, there is insufficient rigorous scientific evidence about the efficiency of herbal TCM for their claimed indications,3 usually due to lack of research publications in English. Consequently, additional controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate their efficacy and risk profile including scientific publications, preferentially in English.5 In Western countries, herbal TCM is considered as natural and erroneously thereby assumed to be safe, delaying recognition of possible side effects and timely treatment discontinuation. Although side effects by herbal TCM in general are rare and mostly transient upon treatment cessation, hepatic adverse reactions may be life threatening, requiring a liver transplant, or both.6–8

This concise article presents for the first time a comprehensive tabular compilation of all potentially hepatotoxic herbal TCMs. These are individually identified by respective references published since 1986. Additional information is provided for the names of the authors, the year of publication, and the overall number of reported cases. Other tabular compilations present results of individual causality assessments by liver specific algorithms and positive reexposure test results.

Literature SearchTo collect all cases of liver injury by herbal TCM, a selective literature search in the PubMed database was performed. We used the search items Traditional Chinese Medicine, TCM, Traditional Asian Medicine, and Traditional Oriental Medicine alone and combined with the terms herbal hepatotoxicity, or herb induced liver injury.

The search was primarily focused on English-language case reports, case series, and clinical reviews, published from 1984 to 15 March, 2014. From each search, the first 25 publications being the most relevant publications were analyzed for subject matter, data quality, and overall suitability. All citations in these publications were searched for other yet unidentified case reports.

Traditional Chinese MedicineTCM is no single entity but encompasses different practices including acupuncture, moxibustion, massage, dietary therapy, and physical exercise such as shadow boxing, with herbal medicines as the most important section.1–3 In Western countries, the use of the name TCM remained unchanged, in recognition of the tradition originating from ancient China. Therefore, we used the term Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) pragmatically as a general term since a regional differentiation would introduce unwanted selection bias effects unrelated to the herbal ingredients. TCM in this review therefore combines Traditional Asian Medicine (TAM), Traditional Oriental Medicine (TOM), Traditional Korean Medicine (TKM), and Traditional Kampo Medicine (TKM) since the principles are identical or vary little between countries. Using TCM as the generic term facilitates and focuses discussions of TCM related issues.

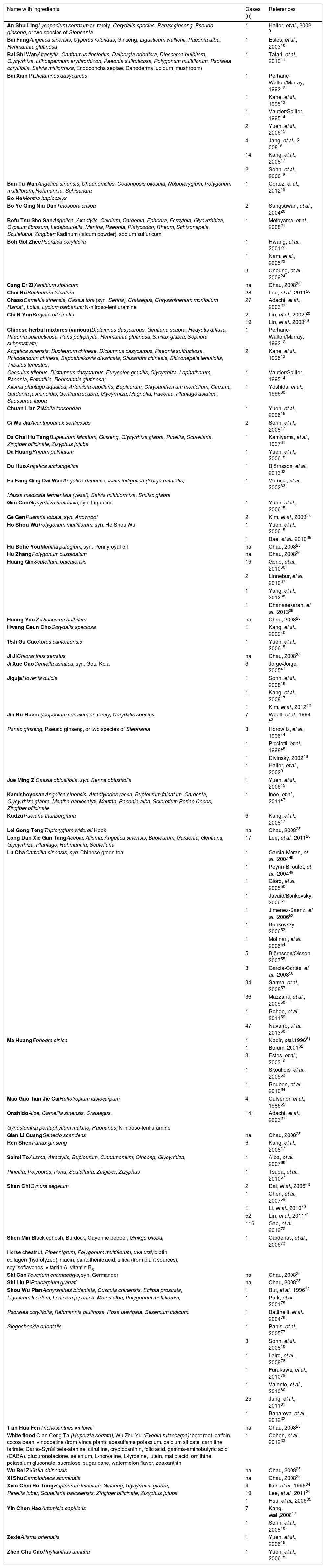

Compilation Of Relevant CasesWe identified 57 different herbs and herbal mixtures of TCM with potential liver injury in 77 case reports and case series (Table 1); their clinical case details were presented earlier.9–87 Such a detailed compilation of cases has not been published before and it may assist clinicians and practitioners evaluating patients with suspected hepatotoxicity by the use of herbal TCM. Three additional reports of hepatotoxicity cases following herbal TCM use were excluded from table 1 because details of the applied herbs were missing.88–90 The figure of 57 different herbs and herbal mixtures compares with 582 medicinal herbs of the Chinese Materia Medica (CMM), which are available in China and are officially recognized and described in detail by the Chinese Pharmacopeia.91,92 If all herbs of widespread use, regional variations, and folk medicine are included, then the total increases to around 13,000 CMM preparations currently in use in China.91,93 Since our review is based on English language case reports, many more than the presently 57 different herbs and herbal mixtures of TCM with potential hepatotoxicity likely exist. This implies that reports in Chinese or other languages are not included, as they are difficult to locate, difficult to evaluate due to language barriers, and difficult to reassess. Nevertheless, a few abstracts have been included in our analysis, if provided in English and considered essential. Consequently, our analysis facilitates wide accessibility and promotes reevaluation but likely covers only a minority of the truly existing cases.

Compilation of reported cases with suspected hepatotoxicity by herbal Traditional Chinese Medicine.

| Name with ingredients | Cases (n) | References |

|---|---|---|

| An Shu LingLycopodium serratum or, rarely, Corydalis species, Panax ginseng, Pseudo ginseng, or two species of Stephania | 1 | Haller, et al., 2002 9 |

| Bai FangAngelica sinensis, Cyperus rotundus, Ginseng, Ligusticum wallichii, Paeonia alba, Rehmannia glutinosa | 1 | Estes, et al., 200310 |

| Bai Shi WanAtractylis, Carthamus tinctorius, Dalbergia odorifera, Dioscorea bulbifera, Glycyrrhiza, Lithospermum erythrorhizon, Paeonia suffruticosa, Polygonum multiflorum, Psoralea corylifolia, Salvia miltiorrhiza; Endoconcha sepiae, Ganoderma lucidum (mushroom) | 1 | Talari, et al., 201011 |

| Bai Xian PiDictamnus dasycarpus | 1 | Perharic-Walton/Murray, 199212 |

| 1 | Kane, et al., 199513 | |

| 1 | Vautier/Spiller, 199514 | |

| 2 | Yuen, et al., 200615 | |

| 4 | Jang, et al., 2 00816 | |

| 14 | Kang, et al., 200817 | |

| 2 | Sohn, et al., 200818 | |

| Ban Tu WanAngelica sinensis, Chaenomeles, Codonopsis pilosula, Notopterygium, Polygonum multiflorum, Rehmannia, Schisandra | 1 | Cortez, et al., 201219 |

| Bo HeMentha haplocalyx | ||

| Bo Ye Qing Niu DanTinospora crispa | 2 | Sangsuwan, et al., 200420 |

| Bofu Tsu Sho SanAngelica, Atractylis, Cnidium, Gardenia, Ephedra, Forsythia, Glycyrrhhiza, Gypsum fibrosum, Ledebouriella, Mentha, Paeonia, Platycodon, Rheum, Schizonepeta, Scutellaria, Zingiber; Kadinum (talcum powder), sodium sulfuricum | 1 | Motoyama, et al., 200821 |

| Boh Gol ZheePsoralea corylifolia | 1 | Hwang, et al., 200122 |

| 1 | Nam, et al., 200523 | |

| 3 | Cheung, et al., 200924 | |

| Cang Er ZiXanthium sibiricum | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Chai HuBupleurum falcatum | 28 | Lee, et al., 201126 |

| ChasoCamellia sinensis, Cassia tora (syn. Senna), Crataegus, Chrysanthenum morifolium Ramat., Lotus, Lycium barbarum; N-nitroso-fenfluramine | 27 | Adachi, et al., 200327 |

| Chi R YunBreynia officinalis | 2 | Lin, et al., 2002;28 |

| 19 | Lin, et al., 200329 | |

| Chinese herbal mixtures (various)Dictamnus dasycarpus, Gentiana scabra, Hedyotis diffusa, Paeonia suffructicosa, Paris polyphylla, Rehmannia glutinosa, Smilax glabra, Sophora subprostrata; | 1 | Perharic-Walton/Murray, 199212 |

| Angelica sinensis, Bupleurum chinese, Dictamnus dasycarpus, Paeonia suffructiosa, Philodendron chinese, Saposhnikovia divaricata, Shisandra chinesis, Shizonepeta tenuifolia, Tribulus terrestris; | 2 | Kane, et al., 199513 |

| Cocculus trilobus, Dictamnus dasycarpus, Eurysolen gracilis, Glycyrrhiza, Lophatherum, Paeonia, Potentilla, Rehmannia glutinosa; | 1 | Vautier/Spiller, 199514 |

| Alisma plantago aquatica, Artemisia capillaris, Bupleurum, Chrysanthemum morifolium, Circuma, Gardenia jasminoidis, Gentiana scabra, Glycyrrhiza, Magnolia, Paeonia, Plantago asiatica, Saussurea lappa | 1 | Yoshida, et al., 199630 |

| Chuan Lian ZiMelia toosendan | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| Ci Wu JiaAcanthopanax senticosus | 2 | Sohn, et al., 200817 |

| Da Chai Hu TangBupleurum falcatum, Ginseng, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Pinellia, Scutellaria, Zingiber officinale, Zizyphus jujuba | 1 | Kamiyama, et al., 199731 |

| Da HuangRheum palmatum | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| Du HuoAngelica archangelica | 1 | Björnsson, et al., 201332 |

| Fu Fang Qing Dai WanAngelica dahurica, Isatis indigotica (Indigo naturalis), | 1 | Verucci, et al., 200233 |

| Massa medicata fermentata (yeast), Salvia milthiorrhiza, Smilax glabra | ||

| Gan CaoGlycyrrhiza uralensis, syn. Liquorice | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| Ge GenPueraria lobata, syn. Arrowroot | 2 | Kim, et al., 200934 |

| Ho Shou WuPolygonum multiflorum, syn. He Shou Wu | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| 1 | Bae, et al., 201035 | |

| Hu Bohe YouMentha pulegium, syn. Pennyroyal oil | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Hu ZhangPolygonum cuspidatum | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Huang QinScutellaria baicalensis | 19 | Gono, et al., 201036 |

| 2 | Linnebur, et al., 201037 | |

| 1 | Yang, et al., 201238 | |

| 1 | Dhanasekaran, et al., 201339 | |

| Huang Yao ZiDioscorea bulbifera | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Hwang Geun ChoCorydalis speciosa | 1 | Kang, et al., 200940 |

| 15Ji Gu CaoAbrus cantoniensis | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| Ji JiChloranthus serratus | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Ji Xue CaoCentella asiatica, syn. Gotu Kola | 3 | Jorge/Jorge, 200541 |

| JigujaHovenia dulcis | 1 | Sohn, et al., 200818 |

| 1 | Kang, et al., 200817 | |

| 1 | Kim, et al., 201242 | |

| Jin Bu HuanLycopodium serratum or, rarely, Corydalis species, | 7 | Woolf, et al., 1994 43 |

| Panax ginseng, Pseudo ginseng, or two species of Stephania | 3 | Horowitz, et al., 199644 |

| 1 | Picciotti, et al., 199845 | |

| 1 | Divinsky, 200246 | |

| 1 | Haller, et al., 20029 | |

| Jue Ming ZiCassia obtusifolia, syn. Senna obtusifolia | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| KamishoyosanAngelica sinensis, Atractylodes racea, Bupleurum falcatum, Gardenia, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Mentha haplocalyx, Moutan, Paeonia alba, Sclerotium Poriae Cocos, Zingiber officinale | 1 | Inoe, et al., 201147 |

| KudzuPueraria thunbergiana | 6 | Kang, et al., 200817 |

| Lei Gong TengTripterygium wilfordii Hook | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Long Dan Xie Gan TangAcebia, Alisma, Angelica sinensis, Bupleurum, Gardenia, Gentiana, Glycyrrhiza, Plantago, Rehmannia, Scutellaria | 17 | Lee, et al., 201126 |

| Lu ChaCamellia sinensis, syn. Chinese green tea | 1 | Garcia-Moran, et al., 200448 |

| 1 | Peyrin-Biroulet, et al., 200449 | |

| 1 | Gloro, et al., 200550 | |

| 1 | Javaid/Bonkovsky, 200651 | |

| 1 | Jimenez-Saenz, et al., 200652 | |

| 1 | Bonkovsky, 200653 | |

| 1 | Molinari, et al., 200654 | |

| 5 | Björnsson/Olsson, 200755 | |

| 3 | García-Cortés, et al., 200856 | |

| 34 | Sarma, et al., 200857 | |

| 36 | Mazzanti, et al., 200958 | |

| 1 | Rohde, et al., 201159 | |

| 47 | Navarro, et al., 201360 | |

| Ma HuangEphedra sinica | 1 | Nadir, etal.199661 |

| 1 | Borum, 200162 | |

| 3 | Estes, et al., 200310 | |

| 1 | Skoulidis, et al., 200563 | |

| 1 | Reuben, et al., 201064 | |

| Mao Guo Tian Jie CaiHeliotropium lasiocarpum | 4 | Culvenor, et al., 198665 |

| OnshidoAloe, Camellia sinensis, Crataegus, | 141 | Adachi, et al., 200327 |

| Gynostemma pentaphyllum makino, Raphanus; N-nitroso-fenfluramine | ||

| Qian Li GuangSenecio scandens | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Ren ShenPanax ginseng | 6 | Kang, et al., 200817 |

| Sairei ToAlisma, Atractylis, Bupleurum, Cinnamomum, Ginseng, Glycyrrhiza, | 1 | Aiba, et al., 200766 |

| Pinellia, Polyporus, Poria, Scutellaria, Zingiber, Zizyphus | 1 | Tsuda, et al., 201067 |

| Shan ChiGynura segetum | 2 | Dai, et al., 200668 |

| 1 | Chen, et al., 200769 | |

| 1 | Li, et al., 201070 | |

| 52 | Lin, et al., 201171 | |

| 116 | Gao, et al., 201272 | |

| Shen Min Black cohosh, Burdock, Cayenne pepper, Ginkgo biloba, | 1 | Cárdenas, et al., 200673 |

| Horse chestnut, Piper nigrum, Polygonum multiflorum, uva ursi; biotin, | ||

| collagen (hydrolyzed), niacin, pantothenic acid, silica (from plant sources), | ||

| soy isoflavones, vitamin A, vitamin B6 | ||

| Shi CanTeucrium chamaedrys, syn. Germander | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Shi Liu PiPericarpium granati | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Shou Wu PianAchyranthes bidentata, Cuscuta chinensis, Eclipta prostrata, | 1 | But, et al., 199674 |

| Ligustrum lucidum, Lonicera japonica, Morus alba, Polygonum multiflorum, | 1 | Park, et al., 200175 |

| Psoralea corylifolia, Rehmannia glutinosa, Rosa laevigata, Sesemum indicum, | 1 | Battinelli, et al., 200476 |

| Siegesbeckia orientalis | 1 | Panis, et al., 200577 |

| 3 | Sohn, et al., 200818 | |

| 1 | Laird, et al., 200878 | |

| 1 | Furukawa, et al., 201079 | |

| 1 | Valente, et al., 201080 | |

| 25 | Jung, et al., 201181 | |

| 1 | Banarova, et al., 201282 | |

| Tian Hua FenTrichosanthes kirilowii | na | Chau, 200825 |

| White flood Qian Ceng Ta (Huperzia serrata), Wu Zhu Yu (Evodia rutaecarpa); beet root, caffein, cocoa bean, vinpocetine (from Vinca plant); acesulfame potassium, calcium silicate, carnitine tartrate, Carno-Syn® beta-alanine, citrulline, cryptoxanthin, folic acid, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glucuronolactone, selenium, L-norvaline, L-tyrosine, lutein, malic acid, ornithine, potassium gluconate, sucralose, sugar cane, watermelon flavor, zeaxanthin | 1 | Cohen, et al., 201283 |

| Wu Bei ZiGalla chinensis | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Xi ShuCamptotheca acuminata | na | Chau, 200825 |

| Xiao Chai Hu TangBupleurum falcatum, Ginseng, Glycyrrhiza glabra, | 4 | Itoh, et al., 199584 |

| Pinellia tuber, Scutellaria baicalensis, Zingiber officinale, Zizyphus jujuba | 19 | Lee, et al., 201126 |

| 1 | Hsu, et al., 200685 | |

| Yin Chen HaoArtemisia capillaris | 7 | Kang, etal.,200817 |

| 1 | Sohn, et al., 200818 | |

| ZexieAlisma orientalis | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

| Zhen Chu CaoPhyllanthus urinaria | 1 | Yuen, et al., 200615 |

Data are retrieved from a selective literature search for published cases of herbal TCM associated with suspected hepatotoxicity. In some cases, causality for individual herbs and herbal mixtures was established using the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) scale or its modifications, and by positive reexposure test results. For other cases, information was fragmentary and did not necessarily allow a firm causal attribution. Details are provided by the original reports referenced above and by other articles.86,87

Botanical names of herbs are provided, which were used individually or as combination partners of herbal mixtures (Table 1). These names were retrieved from the published reports and verified through an internet search. The herbs were not always further specified, because relevant data often were contradictory and insufficiently described in the publications. One TCM name may be used for various preparations in China, but not necessarily in other countries. Among these are prepared decoction pieces (known as Yin Pian), extracts or granules of the decoction pieces (known as Keli), as well as unprepared and crude material.1 Of particular importance are Proprietary Chinese Medicines (PCM) products known as Zhong Cheng Yao, which must be approved by the China FDA before marketing.1 Unapproved PCM products are regarded illegal medicines and are commonly of poor quality, shortcomings likely applying to other countries as well.

The reference list for the reports mentioned in table 1 allows information for number and period of publication. In the years 1984 to 1993, 1994 to 2003, and 2004 to 2013, there were 2, 20, and 55 publications for the respective periods. With 28 and 27 publications for 2004 to 2008 and for 2009 to 2013, the publication frequency was stable within the last decade. Hepatotoxicity by herbal TCM is reported from many countries around the world with various publications9–90 from China, 4; Hong Kong, 5; Taiwan, 4; Japan, 9; Korea, 10; Thailand, 1; Australia, 2; Slovakia, 1; Italy, 5; Spain, 3; France, 2; the Netherlands, 1; the United Kingdom, 4; Denmark, 1; Iceland, 2; Canada, 2; the United States, 20; and Argentina, 1.

Herbal hepatotoxicity is not limited to herbal TCM but also occurs worldwide with numerous other herbs.7,8 Among sixty different herbs or herbal mixtures with hepatotoxic potential identified in a recent study, which analyzed 185 published reports, only few were TCM herbs.7 Overt differences of hepatotoxicity between TCM herbs and non TCM herbs are lacking in clinical presentation, types of liver injury, latency period, dechallenge characteristics, and reexposure characteristics, when comparing the original publications for the present analysis (9-85) with those of the previous publications.7,8 Both groups have a similar incidence of severity, liver transplantation, and lethal outcome.

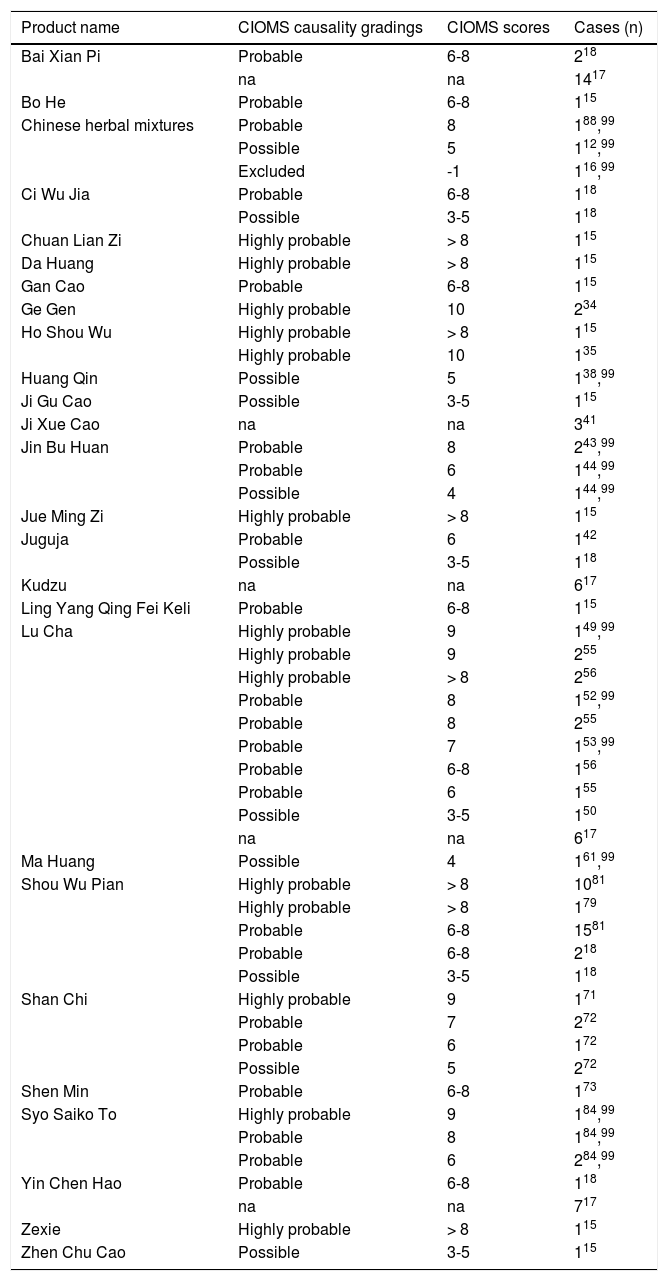

Causality AssessmentIn patients with suspected herbal liver injury by TCM, the key question is the diagnostic validity. Hepatotoxicity requires strict criteria, best defined by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) values.94,95 Its increase is converted into multiples of the upper limit of their normal range, given as N. For ALT, hepatotoxicity has been defined as increases of > 2N, > 3N or > 5N, while ALP values of > 2N are commonly considered diagnostic.96,97 Restricting only ALT increases of > 5N as diagnostic eliminates false positive cases and substantiates causality at a higher level of probability. Considering ALT > 2N as hepatotoxic will include numerous patients with nonspecific increases, with higher requirements for thorough assessment and more stringent exclusion of causes unrelated to the herb(s) under discussion. Also for low threshold N values, more diagnostic alternatives must be ruled out; missing an exclusion of a hepatotoxicity case results in overdiagnosing and overreporting with false high case numbers.96 Commonly an ALT cutoff point of 5N is used, or an ALT cutoff of 3N if the total bilirubin exceeds 2N; for ALP, 2N is considered an appropriate definition criterion.96,97 These criteria are likely fulfilled by most reports included in this review, even considering that N values are rarely mentioned, and some publications do not mention any liver values at all.9–85 Applying these criteria, the herbal TCM Ba Jiao Lian (Dysosma pleianthum) was not proven hepatotoxic, although this was initially assumed.86,98 Therefore, Ba Jiao Lian is not included as a hepatotoxin in this review of TCM. Valid diagnostic biomarkers in patients with suspected herbal hepatotoxicity currently are lacking,8 except for pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) where quantification of protein adducts and GSH conjugates in the blood allows intake quantification.72,86 Considering these limitations and the need of early evaluation of suspicious cases, the best approach for quick assessment is the combination of clinical judgement and a liver specific causality assessment algorithm like the scale of CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences), also called RUCAM (Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method).94,95 This CIOMS scale has been used in cases of herbal TCM hepatotoxicity and commonly provides high quality classifications of highly probable and probable cases initially (Table 2) or after reassessment.99 In some cases, a previous CIOMS version100 or a modified CIOMS version101 was used for assessment (Table 2). Although commonly recommended,102 overall CIOMS based evaluations were done in only 18 reports (Table 2), not in the remaining 59 publications analyzed in the present review (Table 1). In the future, therefore, all suspected cases should undergo CIOMS assessment to improve case data evaluation.

Reported causality assessment by the CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences) scale in cases of assumed herbal hepatotoxicity by Traditional Chinese Medicine.

| Product name | CIOMS causality gradings | CIOMS scores | Cases (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bai Xian Pi | Probable | 6-8 | 218 |

| na | na | 1417 | |

| Bo He | Probable | 6-8 | 115 |

| Chinese herbal mixtures | Probable | 8 | 188,99 |

| Possible | 5 | 112,99 | |

| Excluded | -1 | 116,99 | |

| Ci Wu Jia | Probable | 6-8 | 118 |

| Possible | 3-5 | 118 | |

| Chuan Lian Zi | Highly probable | > 8 | 115 |

| Da Huang | Highly probable | > 8 | 115 |

| Gan Cao | Probable | 6-8 | 115 |

| Ge Gen | Highly probable | 10 | 234 |

| Ho Shou Wu | Highly probable | > 8 | 115 |

| Highly probable | 10 | 135 | |

| Huang Qin | Possible | 5 | 138,99 |

| Ji Gu Cao | Possible | 3-5 | 115 |

| Ji Xue Cao | na | na | 341 |

| Jin Bu Huan | Probable | 8 | 243,99 |

| Probable | 6 | 144,99 | |

| Possible | 4 | 144,99 | |

| Jue Ming Zi | Highly probable | > 8 | 115 |

| Juguja | Probable | 6 | 142 |

| Possible | 3-5 | 118 | |

| Kudzu | na | na | 617 |

| Ling Yang Qing Fei Keli | Probable | 6-8 | 115 |

| Lu Cha | Highly probable | 9 | 149,99 |

| Highly probable | 9 | 255 | |

| Highly probable | > 8 | 256 | |

| Probable | 8 | 152,99 | |

| Probable | 8 | 255 | |

| Probable | 7 | 153,99 | |

| Probable | 6-8 | 156 | |

| Probable | 6 | 155 | |

| Possible | 3-5 | 150 | |

| na | na | 617 | |

| Ma Huang | Possible | 4 | 161,99 |

| Shou Wu Pian | Highly probable | > 8 | 1081 |

| Highly probable | > 8 | 179 | |

| Probable | 6-8 | 1581 | |

| Probable | 6-8 | 218 | |

| Possible | 3-5 | 118 | |

| Shan Chi | Highly probable | 9 | 171 |

| Probable | 7 | 272 | |

| Probable | 6 | 172 | |

| Possible | 5 | 272 | |

| Shen Min | Probable | 6-8 | 173 |

| Syo Saiko To | Highly probable | 9 | 184,99 |

| Probable | 8 | 184,99 | |

| Probable | 6 | 284,99 | |

| Yin Chen Hao | Probable | 6-8 | 118 |

| na | na | 717 | |

| Zexie | Highly probable | > 8 | 115 |

| Zhen Chu Cao | Possible | 3-5 | 115 |

For the listed numbers of cases, the respective publication is provided as superscript. Most listed cases were assessed by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) scale,94,96 single cases by an earlier CIOMS version100 or by a modified CIOMS version.101 In some original reports, CIOMS causality grading was presented without any individual CIOMS score, so the range of the scores was provided in this table rather than an accurate score number. In one publication of a case series, data of the scores were presented only as means17 and therefore classified in the table as not available, since individual scores were not provided. Abbreviation: na, not available.

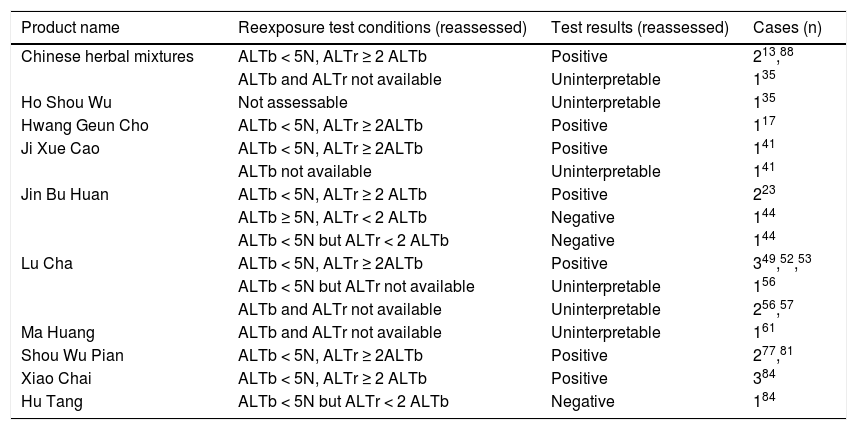

A positive reexposure test result commonly is considered as the gold standard to verify the diagnosis of herb induced liver injury.86,99,103 Since reexposure tests are unintentional and therefore not planned in advance, these cases also have to be analyzed in retrospect. Consequently, under these circumstances case data often are of poor quality, lacking basic criteria for a positive test result. In 25 cases of suspected herbal TCM hepatotoxicity, the authors claimed a positive reexposure test (Table 3); however, in only 14 cases this result was confirmed upon reassessment, when specific and accepted criteria were applied (Table 3).86,99 In the remaining nine patients, the evaluation was either negative or uninterpretable. Intentional reexposure tests are unethical and obsolete due to high risks.

Causality reassessment of positive reexposure test results initially reported in original publications for cases of herbalhepatotoxicity by Traditional Chinese Medicine.

| Product name | Reexposure test conditions (reassessed) | Test results (reassessed) | Cases (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese herbal mixtures | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2 ALTb | Positive | 213,88 |

| ALTb and ALTr not available | Uninterpretable | 135 | |

| Ho Shou Wu | Not assessable | Uninterpretable | 135 |

| Hwang Geun Cho | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2ALTb | Positive | 117 |

| Ji Xue Cao | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2ALTb | Positive | 141 |

| ALTb not available | Uninterpretable | 141 | |

| Jin Bu Huan | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2 ALTb | Positive | 223 |

| ALTb ≥ 5N, ALTr < 2 ALTb | Negative | 144 | |

| ALTb < 5N but ALTr < 2 ALTb | Negative | 144 | |

| Lu Cha | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2ALTb | Positive | 349,52,53 |

| ALTb < 5N but ALTr not available | Uninterpretable | 156 | |

| ALTb and ALTr not available | Uninterpretable | 256,57 | |

| Ma Huang | ALTb and ALTr not available | Uninterpretable | 161 |

| Shou Wu Pian | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2ALTb | Positive | 277,81 |

| Xiao Chai | ALTb < 5N, ALTr ≥ 2 ALTb | Positive | 384 |

| Hu Tang | ALTb < 5N but ALTr < 2 ALTb | Negative | 184 |

For the llisted numbers of cases, the respective publications are provided as superscripts. Clinical details and laboratory valueswere obtained from the original reports, which all described a positive reexposure test result without providing specific criteria.For all 25 cases, reassessment of the reexposure test data was done applying established and strict criteria,86,99 and the reassessedtest results are presented in the table. These results showed a positive causality only in 14 cases, without firm causalityin nine cases as claimed in the original reports. Criteria for the hepatocellular type of liver injury99,103 are the ALT levels atbaseline before reexposure (ALTb), and the ALT levels during reexposure (ALTr). Response to reexposure is considered positive if ALTr ≥ 2ALTb and ALTb < 5N, with N as the upper limit of the normal value. Other combinations result in negative causality or uninterpretableresults.ALT: alanine aminotransferase. n: upper limit of normal.

Among the reported cases of herbal hepatotoxicity (Table 1), causality was verified by CIOMS scale grades, positive reexposure tests, or both for 27 different herbs and herbal mixtures (Tables 2 and 3), out of a total of 57 (Table 1). These included Bai Xian Pi, Bo He, Ci Wu Jia, Chuan Lian Zi, Da Huang, Gan Cao, Ge Gen, Ho Shou Wu, Huang Qin, Hwang Geun Cho, Ji Gu Cao, Ji Xue Cao, Jin Bu Huan, Jue Ming Zi, Juguja, Kudzu, Ling Yang Qing Fei Keli, Lu Cha, Rhen Shen, Ma Huang, Shou Wu Pian, Shan Chi, Shen Min, Syo Saiko To, Xiao Chai Hu Tang, Yin Chen Hao, Zexie, and Zhen Chu Cao. Causality was also established in two unclassified Chinese herbal mixtures (Table 2), from five mixtures initially included (Table 1).

Herbal Misidentification, Contamination, and AdulterationIt is well recognized that herbal products conform only to fewer quality standards than chemical drugs.7,8,104,105 This also applies to most herbal TCM products used worldwide.94,91,106–108 In China, strict regulations exist for China FDA approved herbal TCM products, ameliorating this problem.1

In the presently analyzed reports, botanical authenticity of individual herbal ingredients mostly was not published, with exceptions related to An Shu Ling,9,86 Chi R Yun (Breynia officinalis) and Yi Yi Qiu (Securinega suffruticosa),28,29,68–72,86,109,110 Jin Bu Huan and Hua Nan Yuan Zhi (Polygala chinensis),43,44 Shan Qi (Gynura segetum) and Jing Tian San Qi (Sedum aizoon),68–72,86,109,110 Shan Qi (Gynura segetum) and Mao Guo Tian Jie Cai (Heliotro-pium lasiocarpum),65,111,112as well as Shou Wu Pian.74 For some herbal TCM products, problems have been identified in misidentification on package insert43,44,60,106 including mistaken herb identity,28,29,44,65,68–72,86,108–113 and insufficient sample amounts.113

Another concern for human use is the possible contamination with dust, pollens, insects, rodents, parasites, microbes, fungi, moulds, toxins, and pesticides.107,113 Also reported was contamination with hepatotoxic seeds20 as well as heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury, and lead.86,107,113 These shortcomings are well recognized1–4 and require stringent controls by producers and regulatory agencies.1 Analyses for contamination were rarely done, except for the herbal mixtures Chaso and Onshido, where contamination with heavy metals like copper, lead, bismuth, cadmium, antimony, tin, mercury, and chromium was not found.27 Contaminants also were lacking in Jin Bu Huan.43,44 In other Chinese herbal mixtures, aflatoxins,12 fungi,12 heavy metals,12 and PAs were excluded,16 but insect fragments (Cryptotympane pustulata) were present in the preparations.12 The TCM Hai Piao Xiao (Endoconcha sepiae) and Ling Zhi (Ganoderma lucidum, mushroom) are listed as ingredients of Bai Shi Wan (Table 1) 11

Even (criminal) adulterations of herbal TCM products with synthetic drugs not declared as such have been published.1,25,91,106,107 Analysis for possible adulterants were rarely done and usually negative.43,44 Adulteration of the herbal TCM products Chaso and Onshido27 and other TCM products14 by the synthetic N-nitroso-fenfluramine was found,15,27 but its hepatotoxic property has not been established.27,86 N-nitroso-fenfluramine therefore is merely an adulterant that is not related to liver injury86 observed in the reported cases.15,27 Neither Chaso nor Onshido are registered by the China FDA; but were produced by Chinese manufacturers and exported to Japan until retracted from the market.27 Actually, China FDA has established analytical methods and product inspections to provide consumer safety.1 Especially for unregistered products, adulteration with chemical compounds remains a problem in China and other countries.

Non Herbal TCMUncertainty of and concern for hepatotoxicity exists also related to the use of non-herbal TCM elements.15,17,18,25,48,91,114–118 They are commonly consumed together with herbal TCM products15,91 and occasionally even named identically.91 Known or potentially hepatotoxic non-herbal TCM elements are Bai Hua She (venom of the Chinese viper Agkistrodon acutus),15Jiang Can (dried larvae of Bombyx Batryticatus, infected by Batrytis bassiana),15Ling Yang Qing Fei (antelope horn),15 Liyu Danzhi (carp juice),114 Quan Xie (dry polypides of the scorpion Buthus martensii),15Sang Hwang (Phellinus lihnteus, mushroom),17,18 Song Rong (Agaricus blazei, Himematsutake as Japanese Kampo Medicine, mushroom),115 Wu Gong (dried polypites of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans),15Wu Shao She (syn. Wu Xiao She, Sheng Wu Shao She, parts of the snake Zaocys dhumnades),15and Yu Dan (fish gallbladder).116–118 Details of their adverse properties to date often remain unexplored for some products.

CochraneThe Cochrane Handbook provides some general recommendations related to adverse effects, especially choosing which adverse effects to include, the types of studies, and search methods for adverse effects.119 These specifications do not necessarily apply to our short analysis, since we focused only on one single adverse effect and did not choose other adverse types. Our report also was based on single case reports or short case series, not on various types of detailed studies which actually are not available in the scientific literature for further assessment by us and others. Finally, specific search methods for hepatotoxicity cases have already been applied in this analysis, and there is no need for additional refinement.

However, the Cochrane Handbook119 was a good basis evaluating and summarizing evidence from the Cochrane Collaboration for traditional Chinese medicine therapies with focus on herbal TCM.120 Overall, 70 Cochrane systematic reviews of TCM were identified, including 42 reviews related to herbal TCM, with 22/42 herbal medicine reviews that concluded that there was not enough good quality trial evidence to make any conclusion about the efficacy of the evaluated treatment, while the remaining 20 herbal TCM reviews indicated a suggestion of benefit, which was qualified by a caveat about the poor quality and quantity of studies. Most reviews included many distinct interventions, controls, outcomes, and populations, and a large number of different comparisons were made, each with a distinct forest plot.120

Considering these uncertainties of therapeutic efficacy as summarized by the Cochrane reviews for herbal TCM120 and the hepatotoxicity risk of herbal TCM use as outlined in the present study (Table 1), the risk/benefit/ratio is clearly negative.

Limitation of the AnalysisProducts of herbal TCM commonly are used as TCM dietary supplements or TCM drugs. Product variability and lack of product standardization regarding their ingredients may create uncertainty and scientific discussions. In addition, listed herbs or products might be arguable as having merely a low affinity to TCM. For many TCM mixtures, only the primary pharmacologically active the other component, called the king herb, is mentioned as ingredient,6 neglecting the other ingredients. This may cause some irritation and discussion due to incomplete product specification.

ConclusionsLiver injury was reported for 57 different TCM herbs and herbal mixtures. Causality was likely or probable for 28 out of these 57 herbal products based on the CIOMS scale, positive reexposure test results, or both, while the remaining cases often remained unassessable. Thus, further efforts are needed to enhance the quality of causality assessment for future cases of suspected herbal hepatotoxicity by TCM; an objective approach like the CIOMS scale should be applied in all cases.

AcknowledgementThe authors declare that they have no conflict on interest.