Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) is a hepatic vascular disease histologically characterized by edema, necrosis, detachment of endothelial cells in small sinusoidal hepatic and interlobular veins and intrahepatic congestion, which leads to portal hypertension and liver dysfunction. In the Western world, most HSOS cases are associated with myeloablative pretreatment in a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation setting. Here we report a case of a 54 years old female patient, otherwise healthy, with no history of alcoholic ingestion, who presented with jaundice and signs of portal hypertension, including ascites and bilateral pleural effusion. She had no history of liver disease and denied any other risk factor for liver injury, except Senecio brasiliensis ingestion as a tea, prescribed as a therapy for menopause. Acute viral hepatitis and thrombosis of the portal system were excluded in complementary investigation, as well as sepsis, metastatic malignancy and other liver diseases, setting a RUCAM score of 6. Computed tomography demonstrated a diffuse liver parenchymal heterogeneity (in mosaic) and an extensive portosystemic collateral venous circulation, in the absence of any noticeable venous obstruction. HSOS diagnosis was confirmed through a liver biopsy. During the following-up period, patient developed refractory pleural effusion, requiring hemodialysis. Right before starting anticoagulation, she presented with abdominal pain and distention, with findings compatible of mesenteric ischemia by computed tomography. A laparotomy was performed, showing an 80cm segment of small bowel ischemia, and resection was done. She died one day after as a result from a septic shock refractory to treatment. The presented case was related to oral intake of S. brasiliensis, a plant containing pyrrolidine alkaloids, which are one of the main causes of HSOS in the East, highlighting the risk of liver injury with herbs intake.

Hepatic sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (HSOS), formerly known as veno-occlusive disease, is a vascular disease characterized by edema, necrosis and detachment of endothelial cells in small sinusoidal hepatic and interlobular veins, with intrahepatic congestion, which leads to portal hypertension and liver dysfunction [1,2]. Because of its presentation, it might be mistaken with decompensated cirrhosis or other forms of acute liver disease, which might delay the diagnosis and thus the proper treatment [3].

HSOS causes varies between West and East – in the latter it is mainly associated with oral ingestion of plants containing pyrrolidine alkaloid (PA), such as Senecio brasiliensis, while in the Western world it is mostly restricted to the hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and myeloablative treatment setting [4].

2Case reportWe present a case of a white woman, 54 years old, with previous history of depression, who was admitted at a hinterland hospital with a report of asthenia and malaise four days before admission. When she started with jaundice, she sought medical help and was promptly hospitalized. The patient denied other comorbidities or use of medications except the daily use of a homemade tea of S. brasiliensis, a native plant to fields of South America prescribed by a healer in the last 20 days as a menopause therapy. Ten days after admission she was transferred to our hospital liver unit. On admission, she denied any history of liver disease, alcohol use and had no liver disease stigmata, as well as no signs of coagulopathy or encephalopathy. Her physical examination showed signs of ascites and bilateral pleural effusion. Tests for acute viral infections (IgM for A and B hepatitis, EBV, HSV, HIV and VZV) were negative, except for a weak positive IgM serology for cytomegalovirus (CMV). CMV IgG antibody affinity was high, with a low CMV viral load, findings interpreted as possible reactivation in a context of critical disease. Autoantibodies, iron and copper metabolism tests performed at admission were also negative. Laboratory values from admission were: aspartate aminotransferase 585, alanine aminotransferase 264, total bilirubin 5.08, alkaline phosphatase 293, γ-glutamyl transferase 452, prothrombin time 15.7s (reference 13s), 175,000 platelets and factor V of 65%.

Abdominal ultrasound showed a normal sized spleen, liver with normal dimensions, smooth contours, discrete heterogeneous echogenicity, periportal edema, portosystemic collateral venous circulation, moderate amount of ascitic fluid and no signs of thrombosis of the hepatic venous portal system and tributaries. Afterwards, thorax and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed moderate bilateral pleural effusion, with no signs of parenchymal disease, while liver showed irregular surface, fissures enlargement, heterogeneity, with portosystemic circulation and paraumbilical vein recanalization, perigastric and periesophageal varices. Portal vein diameter was 1.5cm (normal 1.2cm) and there was a voluminous ascites.

Calculated RUCAM score (Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method), a tool used for quantitatively assess causality in cases of suspected drug or herbal liver injury [5], was 6, compatible with probable injury related to the herbal (2 points for time to onset – between 5 and 90 days, 2 points on course of ALP after drug cessation – 452 initially, 185 twenty days later, 2 points for reaction labeled in the product characteristics).

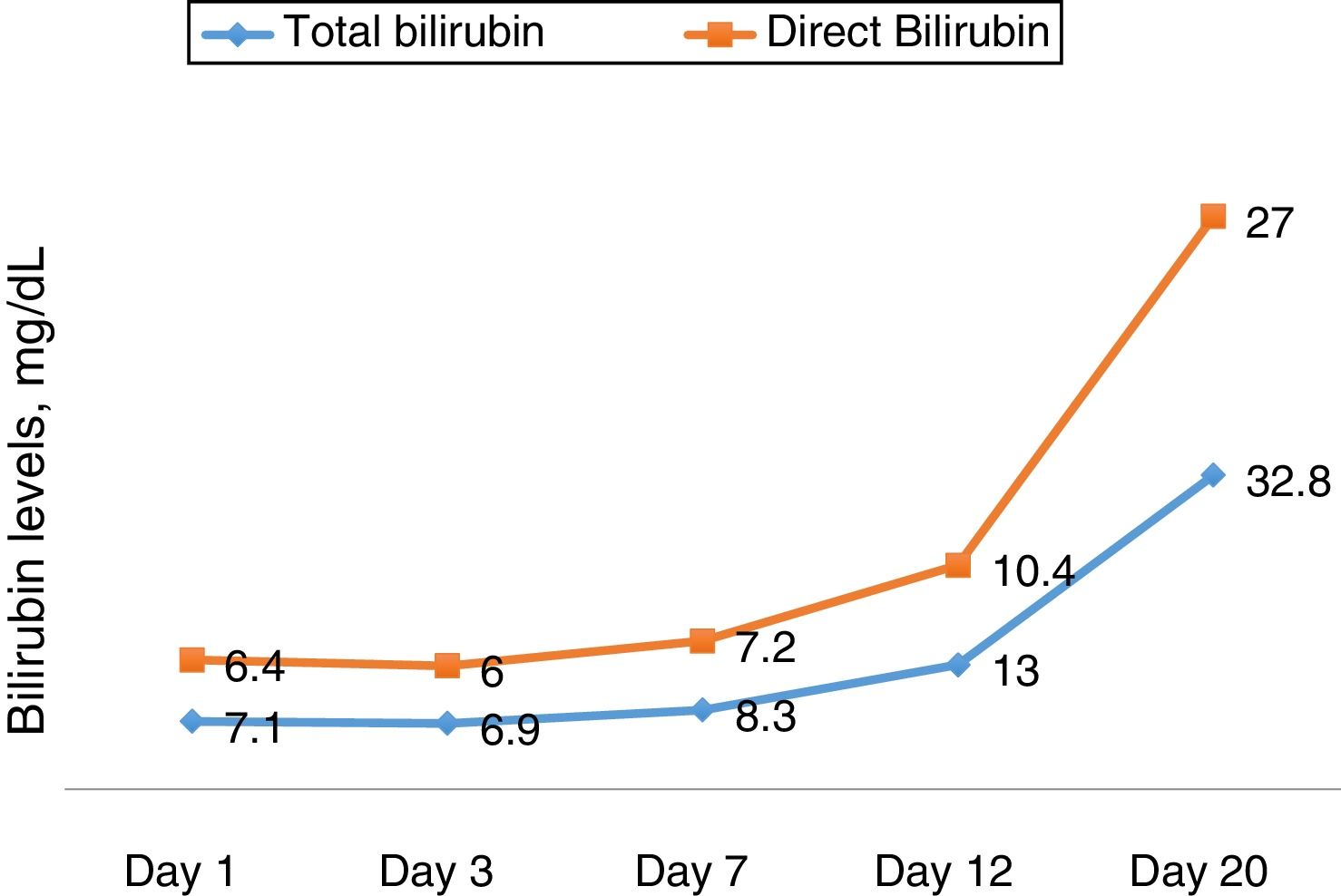

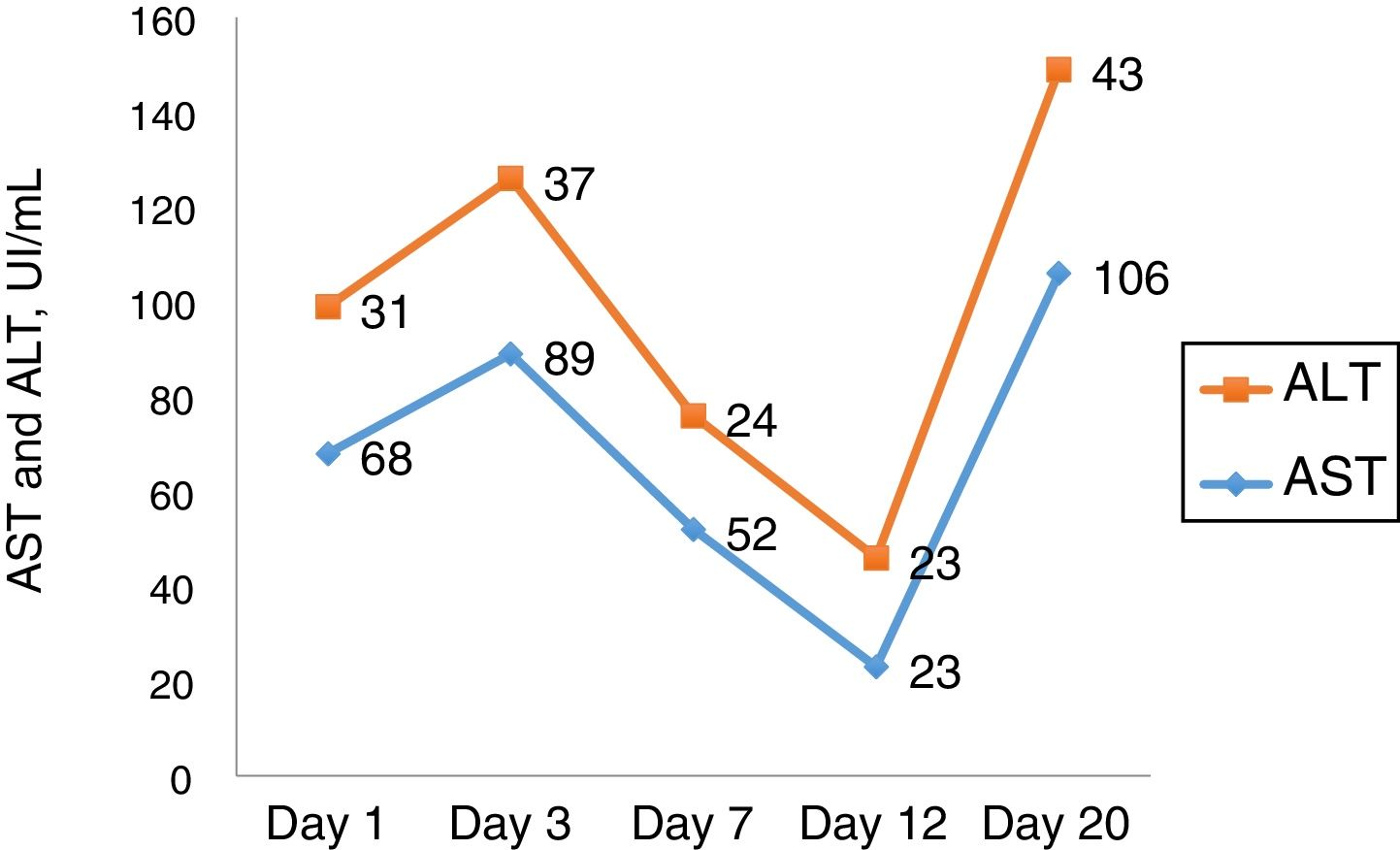

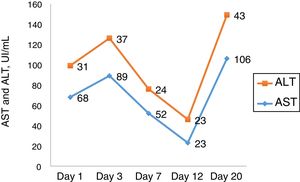

Ascites and pleural effusion were sent to analysis on the first day, and were compatible with transudate, with a high serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) – 1.7. Neutrophil count was higher than 250, and patient was treated as having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, although there was no clear evidence of cirrhosis. Eleven days after admission, she developed a septic shock, evolving with acute respiratory distress syndrome, requiring mechanic ventilation. Her clinical picture improved partially, with extubation, but worsening of mental status (grade II encephalopathy) and persistent renal disfunction, progressing into oliguria and hydroelectrolytic dysbalance, demanding hemodialysis fourteen days after admission. The laboratory curves are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

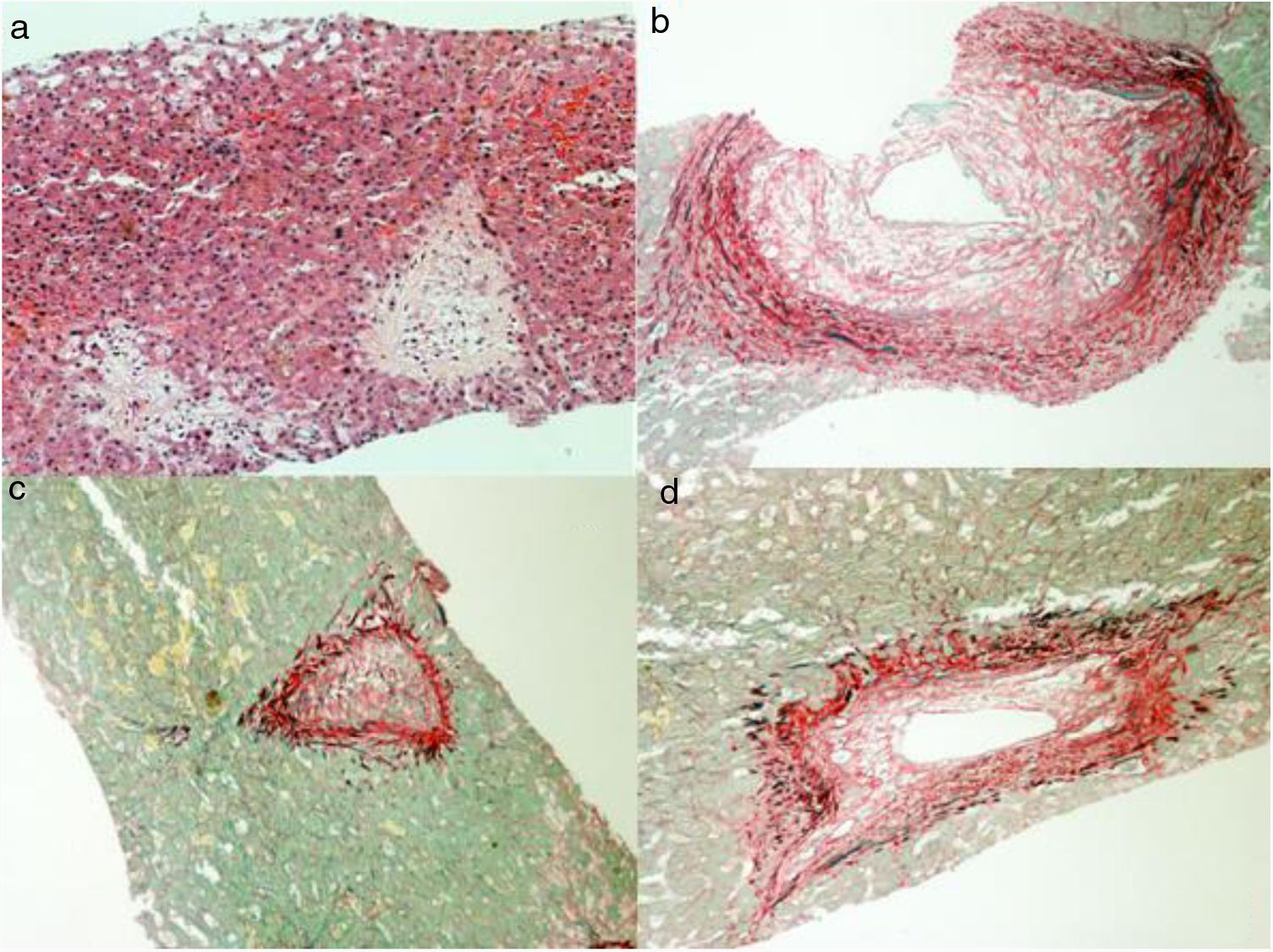

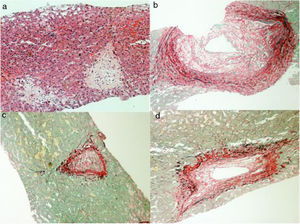

Considering the severity involving the scenario, in spite of removing the causal factor, and having uncertainty about the diagnosis, the patient was submitted to a liver biopsy, which showed a histologic pattern compatible with veno-occlusive disease (Fig. 3). Before starting anticoagulation, in twenty-four days of hospitalization, her clinical state suddenly got worse, showing signs of shock, abdominal distention and pain, along with fecaloid vomit. Urgent CT showed signs of mesenteric ischemia, confirmed by exploratory laparotomy, with resection of an 80cm necrotic small bowel area. Shortly afterwards, despite support, patient evolved to multiple organ dysfunction and death, on the twenty-fifth day of admission.

3DiscussionHSOS has two major causes: cytotoxic or immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, and the ingestion of pyrrolidine agents, such as S. brasiliensis. The syndrome should be suspected in patients with significant portal hypertension in the absence of cirrhosis. Differential diagnosis include Budd-Chiari syndrome, hepatic injury induced by another drugs, acute alcoholic hepatitis, and, in selected cases, decompensated cirrhosis [6].

The main clinical symptoms of patients with PA-HSOS is highly similar to those with HCT-HSOS [7]. The diagnosis of PA-HSOS is based on the patient's history of illness, clinical manifestations, imaging results and pathological features. To facilitate the diagnosis of HCT-HSOS, two different sets of clinical criteria have been described: the revised Seattle and the Baltimore criteria. These are based on the presence of clinical findings (jaundice, weight gain, hepatomegaly and ascites) not attributable to any other possible cause, in the first 3 weeks after HCT [8]. The treatment of PA-HSOS is mainly based on anticoagulation and antithrombotic agents in addition to supportive and liver protective treatments. Although regular heparin or low molecular weight heparin has a strong anticoagulant effect in thrombotic diseases, it has no significant preventive or therapeutic effect in patients with HCT and it increases the risk of bleeding [7]. As a result, regular heparin or low molecular weight heparin is not recommended for the treatment of HCT-HSOS [9]. The efficacy of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) for PA-HCT is controversial. Patients with HCT usually have serious underlying diseases that can affect the efficacy of TIPS [7].

Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are a group of naturally occurring alkaloids based on the structure of pyrrolizidine. The precise mechanism of hepatic injury is unknown but appears to result from accumulation of highly reactive electrophilic metabolites produced via P450 cytochrome enzyme system. The increased concentration of P450 enzymes within the hepatic centrilobular region correlates with the changes seen histologically [10].

Liver is the main target of pyrrolidine's alkaloids, modifying sodium-potassium pump on liver's membrane, causing endothelial edema on the hepatic vein, stenosis of the centric hepatic venous lumen, zone III necrosis and congestion of the hepatic sinusoids [11,12]. Mortality rate varies according cause, severity, disease's evolution and therapy instituted, but normally exceeds 40% [13,14]. The main clinical features are abdominal distention, right hypochondrium pain, anorexia, malaise, ascites, jaundice and hepatomegaly [15]. Most patients presents with symptoms within one month after the ingestion. A significant portion of patients with severe disease or without response to the treatment have progressive exacerbations, complicated by infection – mostly respiratory – and acute hepatic or renal failure, as our patient had [16].

HSOS may be accompanied by progressive thrombocytopenia. The main hepatic manifestations are elevation of bilirubin, cholestasis markers and aminotransaminases. Prothrombin time is generally normal or slightly prolonged. Ascites usually had portal hypertension characteristics, with a SAAG above 1.1g/L [17].

Ultrasonography have a diagnosis value, depending on the expertise of the physician. Typical findings include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, thickening of gallbladder's walls, dilated portal vein (>12mm diameter) and narrowing of the hepatic veins [18]. Abdominal CT often shows hepatomegaly, low density and heterogeneity of hepatic parenchyma [19]. Hypodensity hepatic areas, within the venous phase, correlate to blood stasis inside the hepatic sinusoids [20,21]. Magnetic resonance's findings are similar [22,23].

HSOS differs from most other liver diseases in which circulatory changes are the cause rather than the consequence of the liver injury. Impairment of circulation leads to hepatocyte necrosis and eventual liver failure. Although early studies and the original name of the disease (hepatic veno-occlusive disease) suggest that SOS originates in the hepatic veins, analysis of clinical material demonstrated that the critical change is obstruction at the sinusoids with increased frequency of involvement of the central veins in more severe cases [22,23].

Liver biopsy is an option to confirm the diagnosis in suspected patients, mainly those with abnormal and atypical laboratory/imaging findings, and shows significant dilation and congestion of zone III's hepatic sinusoids, various degrees of edema and necrosis of hepatocytes, interlobular veins’ endothelial cells injury and edema. The first pathological changes involve damage to the microscopic anatomy of hepatic sinusoid endothelial cells, followed by the development of hepatic sinusoid obstruction, endothelial cell damage, and impaired integrity of sinusoid walls, with hepatic sinusoid congestion. Pathological manifestations in the acute phase include hepatocellular necrosis, endothelial swelling of the hepatic vein, thickening of the hepatic vein walls, and significant expansion and congestion of the sinuses. The pathological manifestations among patients in the subacute and chronic phases included central lobular fibrosis and non-portal liver cirrhosis, the latter particularly in the chronic phase [19,24,25].

The main treatment consists of suspending the agent causing the syndrome. As with cirrhosis, spironolactone and furosemide are good options for treatment of ascites and pleural effusions, reserving TIPS to refractory ascites [7,26]. Hemodialysis should be an option in case of systemic congestion or acute renal failure. The effectiveness of glucocorticoids is controversial. Pulse therapy can be done, but the risk of infection should be considered, and the degree of evidence is low [27]. Anticoagulant treatment is recommended to be started as soon as possible in cases of acute/subacute presentation. Contraindications include active hemorrhage or tendency to bleeding. Low molecular weight heparin is the first choice, followed by vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin. The recommended dosage for enoxaparin is 1mg BID, subcutaneously, and the majority of patients do not need monitoring. Careful or avoiding should be warranted in chronic renal failure patients. Warfarin is the long term preferred drug, with a target International Normalized Ratio between 2 and 3, for at least 3 months [28,29]. Liver transplantation should be considered to patients with acute liver failure who fail to respond to the clinical treatment [30].

Defibrotide, a complex of single-stranded oligodeoxyribonucleotides derived from porcine or bovine mucosal DNA, is the only effective drug indicated specific to HSOS treatment, but it's not widely available [31]. The mechanism of action is attributed to the protective anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic actions on endothelial cells [31]. A recent systematic analysis showed a 100-day survival of 41–70% [32]. The high cost of defibrotide, however, is an impediment for its use. This drug is not supplied in our healthy system; therefore, it is difficult to use it promptly. Besides that, the published studies and recommendations indicates that defibrotide is an effective therapy for the treatment of HSOS following haemopoietic stem cell transplantation [8,33].

4ConclusionHSOS is a high mortality syndrome. This report highlights the importance of considering this condition as a differential diagnosis in patients with portal hypertension, and also the potential toxic effect concerning use of medicinal plants.AbbreviationsHSOS

sinusoidal obstruction syndrome

PApyrrolidine alkaloid

HCThematopoietic cell transplantation

CMVcytomegalovirus

CTcomputed tomography

SAAGserum-ascites albumin gradient

TIPSTransjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt

Funding sourceThere has been no financial support for this work.

Conflict of interestNone.