Hepatorenal syndrome has the worst prognosis among causes of acute kidney injury in cirrhotic patients. Its definitive treatment is liver transplantation. Nevertheless, considering its high short-term mortality rate and the shortage of liver grafts, a pharmacological treatment is of utmost importance, serving as a bridge to liver transplant. The clinical management of hepatorenal syndrome is currently based on the use of a vasoconstrictor in association with albumin. Terlipressin, noradrenaline and the combination of midodrine and octreotide could be used to treat hepatorenal syndrome. Among these options, terlipressin seems to gather the strongest body of evidence regarding efficacy and should be considered the first line of treatment whenever available and in the absence of contraindications. Treatment with a vasoconstrictor and albumin should be promptly initiated after the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome in order for patients to have higher chances of recovery.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) has a dramatic impact on the prognosis of cirrhotic patients [1]. Around 19% of hospitalized cirrhotic patients have AKI, near 23% of whom have hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) [2]. Therefore, one can easily realize that HRS in not the most common cause of AKI in cirrhotic patients. On the other hand, it is certainly the cause of AKI in cirrhosis with the worst prognosis. In a prospective cohort study of 562 cirrhotic patients with impaired renal function, 3-month survival for those with parenchymal nephropathy, hypovolemia-related renal dysfunction, kidney injury associated with infection, or HRS were 73%, 46%, 31%, and 15%, respectively (p<0.0005) [3].

Despite its dismal prognosis, HRS is considered mostly a functional cause of AKI, not being usually related to significant renal histological damage, and being potentially reversible [1,4–6]. The pathophysiology of HRS relates, among other factors, to the splanchnic vasodilation that is typical of cirrhosis with portal hypertension, leading to effective arterial hypovolemia and to the activation of vasoconstrictor systems, ultimately causing an important vasoconstriction of renal arterial system, renal hypoperfusion and a decrease in glomerular filtration rate. The rationale behind using vasoconstrictors to treat HRS is the attempt of reverting splanchnic vasodilation and its consequences [7].

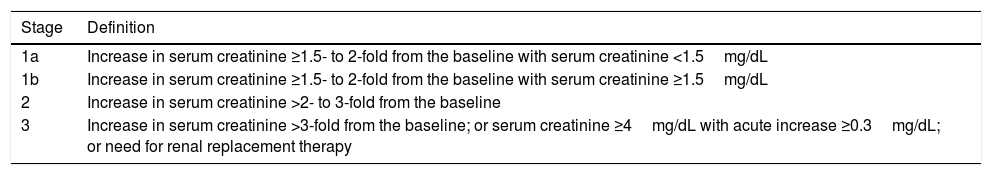

2Diagnosis and initial management of AKI in cirrhosisIn 2015, the International Club of Ascites published its recommendations regarding diagnosis and classification of AKI in cirrhosis, as well as a proposition for its management [1]. Since then, other medical associations have corroborated these recommendations and have made minor improvements [6,8]. Currently, AKI is diagnosed in a cirrhotic patient who develops an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.3mg/dL within 48h or ≥50% from baseline within the prior 7 days. The classification of AKI according to its severity is demonstrated in Table 1[6].

Acute kidney injury classification in cirrhosis.

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1a | Increase in serum creatinine ≥1.5- to 2-fold from the baseline with serum creatinine <1.5mg/dL |

| 1b | Increase in serum creatinine ≥1.5- to 2-fold from the baseline with serum creatinine ≥1.5mg/dL |

| 2 | Increase in serum creatinine >2- to 3-fold from the baseline |

| 3 | Increase in serum creatinine >3-fold from the baseline; or serum creatinine ≥4mg/dL with acute increase ≥0.3mg/dL; or need for renal replacement therapy |

The initial management of AKI stage 1a consists of close monitoring and removal of risk factors for renal impairment. On the other hand, the management of patients with AKI stage >1a requires withdrawal of diuretics and volume expansion with albumin 1g/kg/day for 2 days. If there is a recovery of renal function with such measures, the diagnosis of pre-renal azotemia will be considered. If renal function does not improve, shock is absent, recent use of nephrotoxic substances is excluded, and the possibility of parenchymal nephropathy is considered low (by means of a 24-h urinary protein <500mg, urinary sediment with an erythrocyte count <50 cells per high-power field, and a normal renal ultrasound), the diagnosis of HRS will be considered, and its treatment with albumin and a vasoconstrictor should be initiated if there are no contraindications. For patients with AKI stage 1a who do not recover after initial management, further treatment should be considered in a case-by-case basis [6].

3The role of vasoconstrictors in the management of HRSDespite the fact of liver transplantation being the definitive treatment for HRS, the role of the pharmacological therapy with albumin and a vasoconstrictor is of paramount importance, serving as a bridge to liver transplant, especially considering HRS high short-term mortality rate, as well as the limitations associated to the shortage of liver grafts [6,9,10]. Treatment of HRS using vasoconstrictors has been proved to increase survival [11], and there seems to be an association between the increase in mean arterial pressure caused by vasoconstrictors and the improvement in serum creatinine [12]. Terlipressin, noradrenaline, or midodrine (in combination with octreotide) are the vasoconstrictor drugs recommended for the treatment of HRS [6]. They should be administered with albumin in order to increase effectiveness [13], and the recommended dose of albumin is 1g/kg at the first day (up to 100g) and 20–40g/day for the following days [1,6]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that survival of patients with HRS increases in parallel with the increase in the cumulative dose of albumin [14]. Therefore, we suggest using the dose of albumin of 40g/day whenever possible.

3.1TerlipressinTerlipressin is the most studied drug in the management of HRS [1,6]. This synthetic analog of lysine-vasopressin acts as a potent vasoconstrictor by binding to vasopressin receptor V1 [15,16]. Since its effect on vascular receptor V1 is much greater than that on renal receptor V2, terlipressin promotes selective vasoconstriction of splanchnic circulation [17]. Initial evidence has demonstrated its efficacy and safety in the treatment of HRS type 1 [18,19] and HRS type 2 [20]. Later, 5 well-conducted randomized controlled trials confirmed its efficacy in the management of patients with HRS type 1 [15,21–23] and in a sample of patients with either type of HRS [16]. Such results have been supported by systematic reviews [17,24–27], and some meta-analyses have even demonstrated that terlipressin is able to decrease mortality in patients with HRS [11,28,29].

Terlipressin has also been studied for sepsis-related HRS, leading to improvement of renal function in 67% of patients [30]. Regarding a similar context, a post hoc analysis of the REVERSE trial [23] has demonstrated that patients with HRS associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome had better response to terlipressin than those with HRS but not with systemic inflammatory response syndrome [31]. These results suggest that terlipressin might be even more effective in more severely-ill patients, especially those with the most important inflammatory response and with the greatest impact on hemodynamics.

The traditional strategy to treat HRS with terlipressin is using doses of 0.5–1.0mg every 4–6h as intravenous boluses and doubling the dose every 2 days to a maximum of 12mg/day if creatinine does not decrease by >25%. Treatment can be extended for 2 weeks, but it could be suspended earlier if there is a complete reversal of HRS, and, in the event of HRS recurrence, patients could be retreated the same way [1,5,6]. More recently, though, it has been advocated that terlipressin is used as a continuous intravenous infusion in order to reduce adverse effects [6]. This suggestion is based on a randomized controlled trial which compared terlipressin given as boluses and the drug given as continuous infusion in 78 patients with HRS type 1, showing fewer adverse effects with the latter posology (62.16% vs. 35.29%, p<0.025) [32]. Nevertheless, as we have already pointed out in a previous publication [33], we understand that these findings must be interpreted with caution, since there was a clear trend to worse survival among patients treated with terlipressin given as continuous infusion (69% vs. 53%), though it did not reach statistical significance. Moreover, in that trial, the initial dose of terlipressin given as continuous infusion was lower than that given as boluses, which evidently could have an influence on the adverse effects rate. Finally, a recent network meta-analysis with trial sequential analyses has demonstrated that evidence of efficacy of the treatment of HRS with terlipressin is actually considered strong for HRS type 1 (currently referred to as HRS-AKI) and for terlipressin given as boluses [34]. Considering the potential risks associated to terlipressin, it should not be used in patients with ischemic heart, cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular diseases [6,35].

3.2NoradrenalineSince terlipressin is unavailable in many regions and because it is an expensive drug, noradrenaline has been tested for the treatment of HRS. Noradrenaline is a catecholamine with predominantly α-adrenergic effect, causing vasoconstriction with limited effects on the myocardium and correcting the low systemic vascular resistance associated with HRS. Concerning HRS, noradrenaline was first used together with albumin and furosemide, causing HRS reversal in 10 of 12 treated patients [36]. Noradrenaline is recommended at doses of 0.5–3.0mg/h combined with albumin, with the aim of increasing mean arterial pressure in 10mmHg [6].

Until recently, noradrenaline had been compared to terlipressin in five randomized controlled trials [37–41]. Three of these trials only included patients with HRS type 1 [39–41], while one trial evaluated a mixed population of patients with HRS types 1 and 2 [37], and another was dedicated exclusively to HRS type 2 [38]. None of these studies identified significant difference between these drugs regarding HRS reversal or survival, and, when we performed a meta-analysis, there was also no evidence of significant difference between them [42]. Considering the facts that terlipressin is more expensive than noradrenaline and that noradrenaline requires administration in an intensive care setting, while terlipressin can be administered in a regular ward, we also performed economic analyses, taking into account all direct medical costs involved with both treatment strategies, finally demonstrating that treating patients with terlipressin was actually more economical than with noradrenaline [42,43].

Nevertheless, considering the comparison between noradrenaline and terlipressin, another randomized controlled trial was published in 2018, bringing new insights. In this study, only patients with HRS-AKI who fulfilled criteria for acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) were included, and terlipressin used as continuous infusion led to better rates of HRS reversal (40.0% vs. 16.7%, p=0.004) and to better 28-day survival (48.3% vs. 20.0%, p=0.001) than noradrenaline [44]. These findings might reinforce the idea of terlipressin being more effective in patients with severe inflammatory response and circulatory impairment [31]. Concerning HRS in patients with ACLF, it is also noteworthy that the grade of ACLF seems to be directly related to mortality and inversely related to response to terlipressin: in one study, patients with ACLF grade 1 had 60% of response to terlipressin and 30% of 3-month mortality; patients with ACLF grade 2 had 48% of response to the drug and 50% of mortality; and, finally, those with ACLF grade 3 had 29% of response to treatment and 79% of mortality [45].

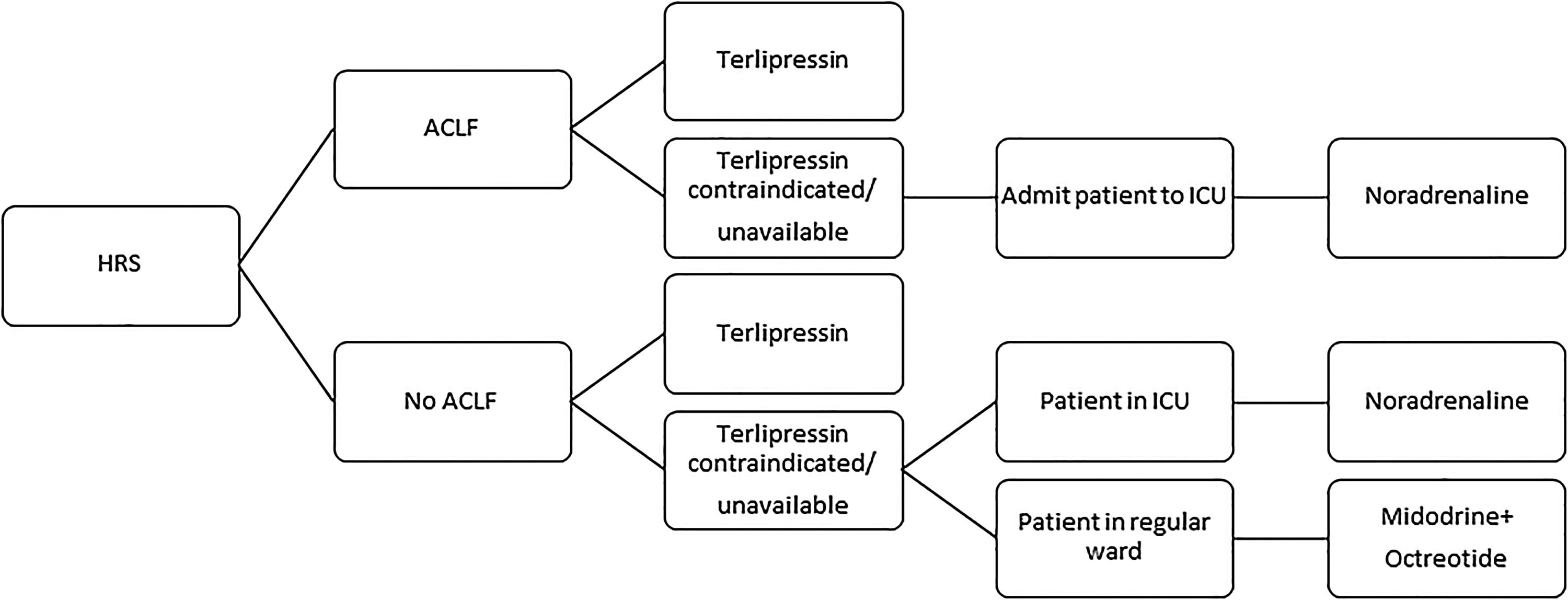

3.3Midodrine and octreotideMidodrine is an α-adrenergic agonist, while octreotide is a somatostatin analog. The association of both drugs has been used for the treatment of HRS, especially in countries where terlipressin is not available. Nevertheless, a recent randomized controlled trial had to be prematurely interrupted owing to the massive superiority of terlipressin over the combination of midodrine and octreotide regarding HRS reversal (55.5% vs. 4.8%, p<0.001). Moreover, despite the absence of statistical significance, there was a clear trend toward better 3-month survival with terlipressin (59.0% vs. 43.0%, p>0.05) [46]. Therefore, the combination of midodrine (orally, at an initial dose of 7.5mg three times a day and at a maximum dose of 12.5mg three times a day) and octreotide (subcutaneously, at an initial dose of 100μg three times a day and at a maximum dose of 200μg three times a day), associated to albumin, should only be used in the treatment of HRS if terlipressin and noradrenaline are unavailable or contraindicated [6]. Considering the abovementioned evidences on the different vasoconstrictors used for HRS, we suggest an algorithm in Fig. 1.

4ConclusionIn conclusion, vasoconstrictors (associated with albumin) have an essential role in the current management of HRS. In this context, terlipressin is the vasoconstrictor which gathers the best evidence, and should be considered as first line pharmacological therapy for HRS whenever available and in the absence of contraindications. A vasoconstrictor associated with albumin should be initiated immediately after the diagnosis of HRS, in order for the patients to have higher chances of achieving HRS reversal and reaching liver transplantation. Despite all the important advances attained in the last decades concerning the treatment of HRS, near half of treated patients do not recover and further developments are still needed in this field of research.

AbbreviationsAKI acute kidney injury hepatorenal syndrome acute-on-chronic liver failure intensive care unit

None.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.