Introduction

Treatments for HIV infection have not achieved a definitive cure, and prevention therefore continues to be the main strategy in the fight against this epidemic.1 The entire population is potentially susceptible to HIV infection; however, the prevalence is much higher in collectives with a higher frequency of risk exposure.1,2 Because prevention is most effective when it is adapted to the characteristics of a specific population, information is needed regarding the main groups who are affected.

By the end of the 1980s the prevalence of HIV infection in Spain had reached high levels: about 50% in intravenous drug users (IVDU), 25% in gay men, 9% in female sex workers, and 7% in persons with heterosexual risk behaviors.3 Since then a number of preventive interventions have been initiated to change the situation,4 and more recent studies have reported decreases in the rates of infection.5-7

The diagnosis of HIV infection and counseling to avoid risk behaviors are aimed at a generally healthy population, and this makes the role of primary care fundamental in providing access to these measures.8,9 However, the high demand for these services in some cities led to the creation of alternative centers and offices specialized in HIV counseling and diagnosis.10 These centers have become reference points for particular collectives who engage in high-risk behaviors, and handle a large number of requests for HIV testing. In the present study we analyze the activity of these alternative centers in 9 cities in Spain, and describe here the prevalence of HIV infection for different types of risk exposure in the population who consulted between 1992 and 2001.

Participants and methods

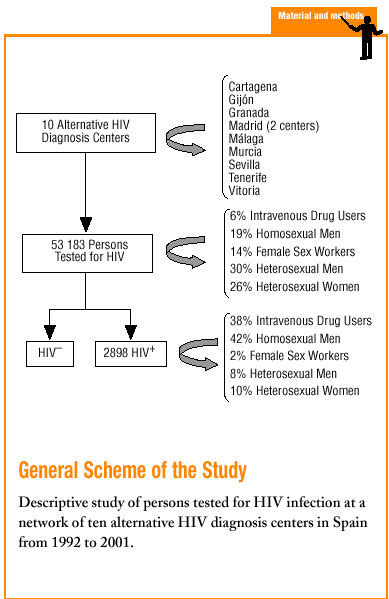

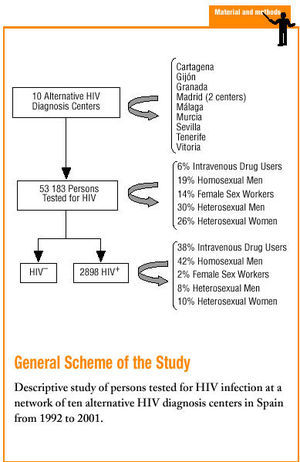

This study was carried out in a network of 10 public health centers specialized in the diagnosis of HIV infection, some of which are also specialized in other sexually transmitted diseases. These centers were located in the cities of Seville, Granada, Malaga, Gijón, Tenerife, Madrid (2 centers), Murcia, Cartagena and Vitoria. All offered free HIV testing on demand, and users were not required to show proof of identity. Patients could provide their own name, an alias or a code name to collect the results and for subsequent medical follow-up. The specially trained health care staff provided preventive counseling when the test was requested, and when the patient returned to collect the results.

In the present analysis we considered all patients older than 12 years who requested their first HIV test at any of the centers during the period from 1992 to 2001. During the interview prior to the test information was recorded on age, sex, intravenous drug use, high-risk sexual exposure involving risk of HIV transmission, and whether the patient was a sex worker. Depending on the type of risk involved, persons were classified into mutually exclusive exposure categories in decreasing order of priority as follows: IVDU, homo- or bisexual men, female sex workers, and heterosexual men and women with no other sources of exposure. For all patients the presence of HIV antibodies was determined in serum samples with an ELISA technique, and positive samples were verified with western blotting or immunofluorescence.

The *2 test was used to compare proportions, and Student's t test was used to compare means.

Results

Description of Persons Who Request HIV Testing

Between 1992 and 2001 a total of 53 183 persons had their first HIV test at these centers. The number of persons tested per year increased by 46%, from 4401 in 1992 to 6407 in 2001. The percentage of women increased from 38.3% in 1992-1993 to 51.6% in 2000-2001 (P<.001). More than half of the persons tested (54.6%) were between 20 and 29 years of age, and this proportion did not change significantly during the study period (Table 1).

About half of the persons tested (excluding sex workers) were heterosexual, and this proportion showed a slight tendency to increase from 49.4% in 1992-1993 to 53.8% in 2000-2001 (P<.001). The number of IVDU decreased by 88%, from 15.3% in 1992-1993 to 1.4% in 2000-2001 (P<.001). In contrast, the proportion of female sex workers showed the greatest increase, from 6.7% to 25.1% (P<.001). The number of homosexual or bisexual men tested remained relatively constant throughout the study period, although the proportion of patients belonging to this group decreased from 23.3% to 16.7% (P<.001) (Table 1).

Description of Persons Diagnosed as Having HIV Infection

During the 10-year study period a total of 2898 HIV infections were diagnosed in patients who came to the centers for the first time. The number of diagnoses decreased by 71%, from 1058 in 1992-1993 to 304 in 2000-2001.

More than three fourths (78%) of the persons diagnosed has having HIV infection were men, and no clear tendency was noted in this percentage. Mean age remained unchanged at about 29 years, and increased only among IVDU, from 27 to 32 years (P<.001).

The number of patients diagnosed as having HIV infection decreased in all exposure categories with the only exception of female sex workers. The greatest decrease was seen in IVDU, from 49.0% of all persons diagnosed in 1992-1993 to 13.5% in 2000-2001 (P<.001). This marked decrease in IVDU was reflected as a corresponding increase in the percentages of patients in all other transmission categories (Table 2).

Evolution of seroprevalence of HIV

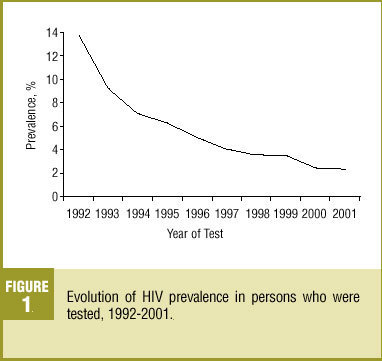

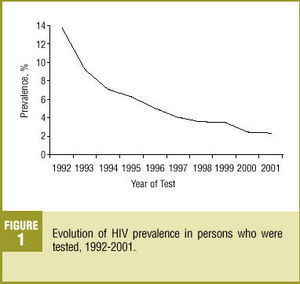

Seroprevalence of HIV in persons who requested the test showed a steady decrease from 14% in 1992 to 2% in 2001 (P<.001), although the decline has slowed in recent years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution of HIV prevalence in persons who were tested, 1992-2001.

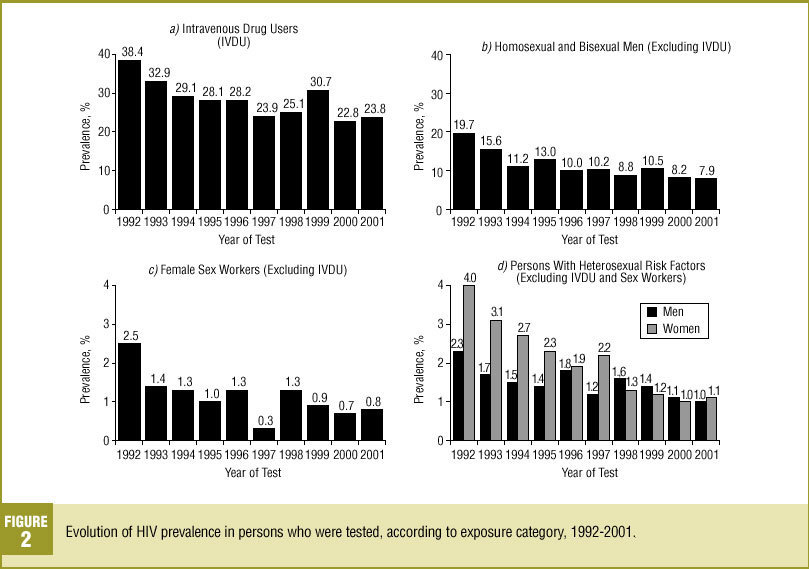

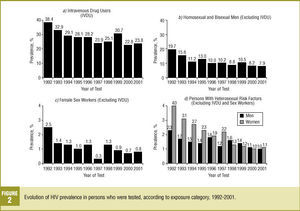

Among IVDU, seroprevalence of HIV decreased from 38.4% in 1992 to 23.8% in 2001 (P=.008) (Figure 2a), but remained much higher than in the rest of the exposure categories. In homosexual and bisexual men, this figure declined during the same period from 19.7% to 7.9% (P<.001). This decrease was more pronounced during the initial years of the study period, but little further decrease was seen during the final years of the study (Figure 2b). In female sex workers the prevalence of HIV infection decreased from 2.5% in 1992 to 0.8% in 2001 (P=.007), although no particular trend was evident during the final years of the study (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Evolution of HIV prevalence in persons who were tested, according to exposure category, 1992-2001.

Among persons exposed via heterosexual risk behaviors the prevalence of HIV infection also decreased in both men and women. In men the prevalence declined from 2.3% in 1992 to 1.0% in 2001 (P=.005). In women the initial prevalence was nearly double that in men at the start of the study (4.0% vs 2.3%; P=.028), so the decrease was more pronounced, such that by the end of the study period the difference between sexes has disappeared (1.0% in men vs 1.1% in women; P=.918) (Figure 2d).

Discussion

This study found a decrease in the prevalence of HIV infection in persons who came for testing between 1992 and 2001 because of possible risk exposure. The prevalence decreased in all exposure categories, and the decreases were more pronounced during the early years of the study, with a trend toward stabilization during the final years. Moreover, we found a clear decrease in the number of IVDU who came to the centers to request their first HIV test. The steady decrease in this exposure category, initially associated with a high prevalence of infection, was a major contributing factor to the decrease in overall prevalence.

This study comprised a large number of participants in widely distant geographical areas within Spain. However, the profile of risk categories for users who came to these centers was different from the overall profile for the HIV epidemic in Spain: in our study homosexual men and female sex workers were over-represented. Moreover, the results should be interpreted in the light of the fact that persons who requested the test voluntarily probably perceived themselves to be at risk.

The yearly increase in the number of persons who came to these centers for the first time to request HIV testing seems to indicate a growing awareness by some collectives of the advantages of knowing ones HIV status.

Among those who requested HIV testing, the decline in the number of IVDU was noteworthy. This is consistent with the decrease in the number of new IVDU observed in Spain, as a result of shifts toward other routes of administration of controlled substances11 and the decline in the number of young IVDU.12,13 In addition, among IVDU we detected a moderate decrease in the prevalence of HIV infection, which reflects a lower risk among injection drug users possibly because of the effect of needle exchange programs.11 These changes have all contributed to the considerable decrease in the number of new infections among IVDU.

The number of female sex workers who request the test has increased considerably in recent years. Information available to date is insufficient to determine whether this is due to an actual increase in the size of this group, or to an increase in the proportion of members who request HIV testing. However, both factors are likely to be involved. Other studies have reported an increase in the presence of immigrant women who work as sex workers in Spain.14 Of the collectives we studied, this group showed the lowest prevalence of HIV infection, with a rate similar to that in the general population of young adults.15

Homosexual men make up a large group of continuous users of these centers. In contrast to IVDU, the number of homosexual men seems to be more stable owing to the steady influx of young men into this group.6 The prevalence of HIV infection in this collective decreased during the initial years of the study, but by the end of the study period the decline had leveled off at rates that can still be considered high. This pattern indicates the persistence of risk behaviors during sexual relations in these men.16

Throughout the study period, the possibility of heterosexual exposure remained the most frequent reason for requesting an HIV test, and this category was equally frequent in men and women after sex workers were excluded. The prevalence of HIV infection in this group has remained higher than in female sex workers. During the early years of the study the prevalence was higher in women than in heterosexual men, possibly because women were more likely to have a sexual partner who was HIV infected.13,17 This prevalence subsequently decreased, and eventually the difference between sexes disappeared.

Once notification systems for HIV infection1,18,19 were established and sentinel physicians were incorporated into primary care,8 we detected a change in the epidemic in Spain. The decrease in the influence of IVDU on the statistics meant that most of the HIV infections diagnosed more recently have been ascribed to sexual transmission.19 However, this effect does not necessarily mean that infections via this route of transmission have increased.

Alternative centers for the diagnosis of HIV infection play an important role in lightening the burden on primary care centers within the health care network, and in facilitating access by some types of patient to preventive counseling and testing. However, these centers are only available certain cities, and their influence is limited to those persons who seek help voluntarily. Therefore these centers cannot take the place of primary care in making diagnostic tests for HIV available to all citizens. Moreover, primary care services are also able to reach persons who, although not considered at risk, may have been exposed to HIV.20 To ensure the availability of adequate care to all persons, these services should incorporate the detection of risk behaviors and preventive counseling for patients who are perceived to be at potential risk of exposure.

Members of the EPI-VIH Group

J. del Romero, C. Rodríguez, S. García, J. Ballesteros, P. Clavo, M.A. Neila, S. del Corral, N. Jerez (Centro Sanitario Sandoval, Madrid); I. Puedo, M.A. Mendo, M. Rubio (Centro de ETS, Sevilla); C. de Armas, E. García-Ramos, M.A. Gutiérrez, J. Rodríguez-Franco, L. Capote, L. Haro, D. Núñez (Centro Dermatológico, Tenerife); J.A. Varela, C. López (Unidad de ETS, Gijón); J.M. Ureña, J.B. Egea, E. Castro, A.M. Calzas, C. García, M. Lorente (Centro de ETS, Granada); F.J. Bru, C. Colomo, R. Martín, A. Comunión (Programa de Prevención del Sida, Madrid); M.V. Aguanell, F. Montiel, A.M. Burgos (Centro de ETS, Málaga); J.R. Ordoñana, J.J. Gutiérrez, J. Ballester, F. Pérez (Unidad de Prevención y Educación sobre Sida, Murcia); J. Balaguer, J. Durán (Centro de Salud Área II, Cartagena); J. Ortueta, L.M. Sáez de Vicuña (Dirección Territorial de Álava); P. Sobrino, A. Barrasa, M.J. Belza, J. Castilla (Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid).