Introducción: La prueba Evaluación del Desarrollo Infantil (EDI) es un instrumento de tamizaje de problemas en el desarrollo diseñado y validado en México. La calificación obtenida se expresacomo semáforo. Se consideran positivos tanto el resultado amarillo como el rojo, aunque seplantea una intervención diferente para cada uno. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar lacapacidad de la prueba EDI para discriminar entre los niños identificados con semáforo amarillo y los identificados con rojo al compararse con el Inventario de Desarrollo de Battelle 2.a edición (IDB-2) en cuanto al cociente de desarrollo del dominio (CDD).

Métodos: El análisis se llevó a cabo utilizando la información obtenida para el estudio de lavalidación. Se excluyeron los pacientes con resultado normal (verde) en EDI. Se utilizaron 2 puntos de CDD (IDB-2) por dominio: < 90 para incluir normal-bajo y < 80 para diagnósticode retraso. Se analizó el resultado con base en la correlación del resultado del semáforo de EDI(amarillo o rojo) y el IDB-2, total y por subgrupos de edad.

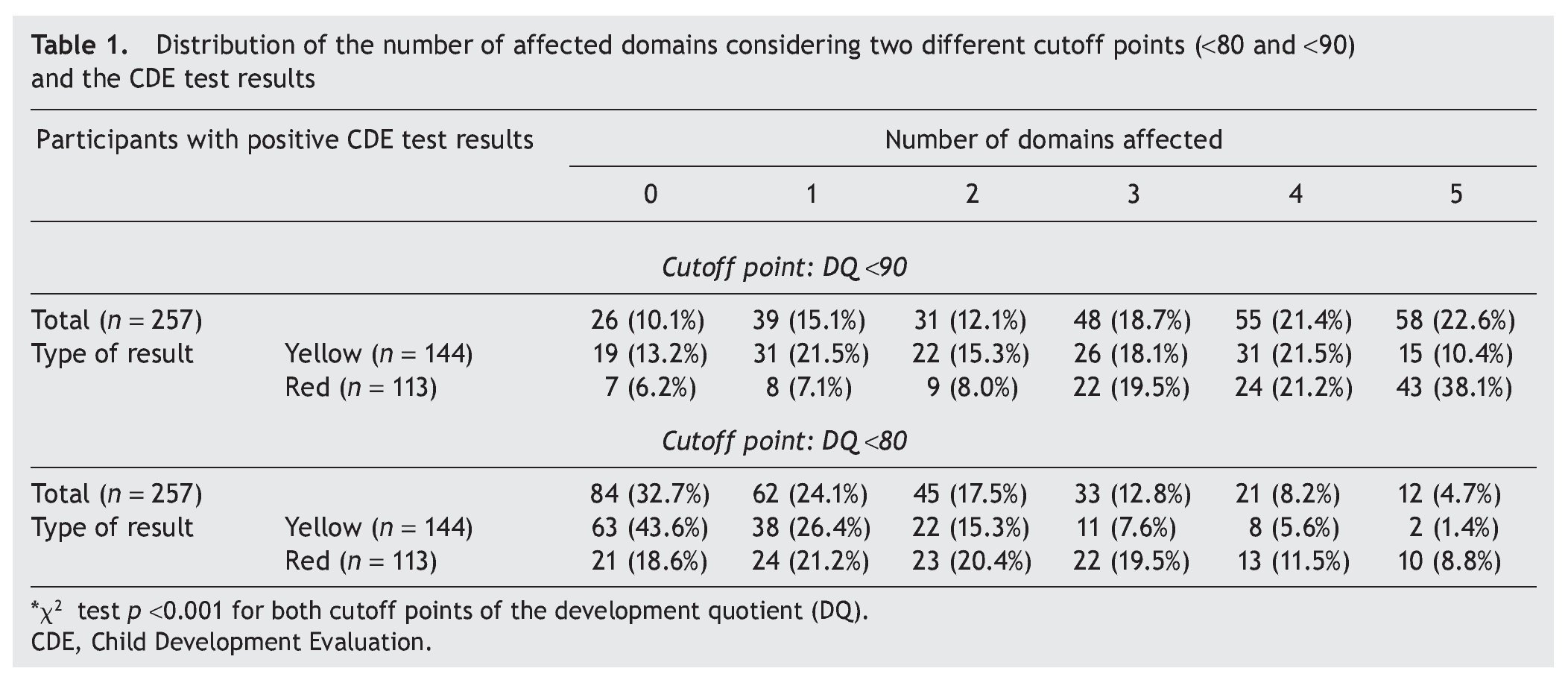

Resultados: Al considerar un CDD < 90 en amarillo, el 86.8% tuvo al menos un dominio afectado,y el 50%, 3 o más dominios, en comparación con el 93.8% y el 78.8% para el resultado en rojo,respectivamente. Hubo diferencias en todos los dominios entre amarillos y rojos (p < 0.001) para el porcentaje de niños con un CDD < 80: cognitivo (36.1 vs. 61.9%); comunicación (27.8 vs. 50.4%); motor (18.1 vs. 39.9%); personal-social (20.1 vs. 28.9%); y adaptativo (6.9 vs. 20.4%).

Conclusiones: Los resultados de semáforo (amarillo o rojo) permiten identificar diferente magnitud de los problemas en el desarrollo y apoyan intervenciones diferenciadas.

Background: The Child Development Evaluation (CDE) is a screening tool designed and validated in Mexico for detecting developmental problems. The result is expressed through a semaphore. In the CDE test, both yellow and red results are considered positive, although a different intervention is proposed for each. The aim of this work was to evaluate the reliability of the CDE test to discriminate between children with yellow/red result based on the developmental domain quotient (DDQ) obtained through the Battelle Development Inventory, 2nd edition (in Spanish) (BDI-2).

Methods: The information was obtained for the study from the validation. Children with a normal (green) result in the CDE were excluded. Two different cut-off points of the DDQ were used (BDI-2): < 90 to include low average, and developmental delay was considered with a cutoff < 80 per domain. Results were analyzed based on the correlation of the CDE test and each domain from the BDI-2 and by subgroups of age.

Results: With a cut-off DDQ <90, 86.8% of tests with yellow result (CDE) indicated at least one domain affected and 50% 3 or more compared with 93.8% and 78.8% for red result, respectively. There were differences in every domain (P < 0.001) for the percent of children with DDQ < 80 between yellow and red result (CDE): cognitive 36.1% vs. 61.9%; communication: 27.8% vs. 50.4%, motor: 18.1% vs. 39.9%; personal-social: 20.1% vs. 28.9%; and adaptive: 6.9% vs. 20.4%.

Conclusions: The semaphore result yellow/red allows identifying different magnitudes of delay in developmental domains or subdomains, supporting the recommendation of different interventions for each one.

1. Introduction

The Child Development Evaluation (CDE) is a screening tool designed to detect problems in neurodevelopment. It was developed in Mexico and is aimed at children from 1 month old until 1 day before reaching 5 years of age. The CDE was developed by a group of experts in Pediatrics, Pediatric Neurology and Psychology in order to have a reliable and easily applicable instrument in primary care. This was determined after analyzing that, despite the existence of validated psychometric tests for the detection of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, there were not any that could be applied to the Mexican population and assist the health system for detection and appropriate treatment.1,2 Currently, most tests to assess neurodevelopment are designed to be used by specialists, and their implementation requires a considerable time investment (and may include many hours), which makes them impractical for use by health care workers at the community level.3

In order to make the CDE a reliable test, the design and development processes were carried out according to the psychometric aspects that determine its validity and reproducibility.4 For this purpose, the panel of experts contributed to the CDE appearance, content and construct validity because it integrates the elements necessary for neurodevelopmental troubleshooting in children <5 years of age, including the following five areas:

1. Biological risk factors (e.g., mother’s age, problems occurring during pregnancy or birth)

2. Warning signs (aspects that may suggest a developmental problem)

3. Alarm signs (in the case of having at least one, the child requires referral and rapid assessment)

4. Neurological examination (movements of the face, eyes and body, head circumference)

5. Areas of development (fine and gross motor skills, language, social and knowledge domains are evaluated)1,2

As part of the preparation process, the panel of experts considered necessary that after the application of the CDE, the assessment conducts interventions or actions to improve the child’s health. Thus, the possible outcomes of the CDE are as follows:

a) Normal development (classified as “green”)—this indicates that the child has reached developmental milestones corresponding to his/her age group and has no warning signs or changes in the axis of the neurological examination.

b) Mild risk for developmental delay (classified as “yellow”)—when a child has not attained the developmental milestones corresponding to his/her age group but meets milestones of the earlier age, has no warning signs, and neurological examination is normal.

c) High risk for developmental delay (classified as “red”)— in this group, the child who has not reached the milestones of his/her age group or the preceding group is considered, either due to an alteration in neurological examination or to the presence of warning signs.1

It should be noted that these three colors were chosen to simulate a traffic light and indicate the actions to be undertaken. Therefore, for those who were classified as yellow (under which there is no clear alteration in neurodevelopment), early stimulation and reassessment within 3 months is recommended; in the case where it is again recorded as yellow, then it should be reclassified within the red group. Meanwhile, when a patient is classified with a red result, an immediate subsequent evaluation is needed to determine the possible cause of the disorder.

According to the CDE, children <16 months of age classified as red should be referred to a pediatrician to rule out any medical conditions (such as hearing or visual impairment, neurological or genetic disease, etc.). In the case of children >16 months of age it is necessary to confirm or rule out developmental delay using one of the tests considered as a gold standard for a reference standard. To accomplish this, a trained psychologist must apply a test such as the Battelle Developmental Inventory 2ª (BDI-2) Spanish edition.5 After confirmation of developmental delay or detection of any specific disease, the child will be referred to the appropriate specialist. Finally, all children classified as green do not require any intervention considering that their development is normal.1 It should be noted that the CDE is a screening test so it does not accurately scan each of the components of neurodevelopment. Therefore, the panel stipulated the need to apply another test to establish with certainty whether or not a child has developmental disorders.

Subsequently, as part of the process to further evaluate whether the CDE met other psychometric properties, a comparison to a gold standard was carried out to determine the criterion validity. To achieve this, 438 children were evaluated using the CDE, BDI-2 and Bayley-III scale. The latter two tests were used as a cutoff to establish that a child had a normal development with a ratio value of the total development quotient (TDQ) ≥90. In the first analysis performed, it was found that the CDE had a sensitivity (capacity to detect developmental problems, cases classified as yellow or red) of 81% (95% CI = 75% to 86%) and specificity (capacity to detect children without developmental problems, cases classified as green) of 61% (95% CI = 54-67%). Whereas the ability to detect normal children was lower, these results established that the CDE is an appropriate screening test once most of children with developmental problems are identified. In this way, the health system is able to provide timely interventional treatment to enhance the capabilities of these children.6

In the analysis described, the information was not disaggregated to document whether there were clinical differences between children classified as yellow or red, which may be important for planning and enabling strategies or differentiated inter ventions in each particular case. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of the CDE to discriminate between children identified as yellow and red as compared to the BDI-2 in terms of TDQ score and scaled domain scores.

2. Methods

This paper is part of a study that was reported previously where the characteristics of the design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data collections methods are disclosed in detail.6 In brief, this was a cross-sectional study in which 438 children from 1 month old until 1 day before reaching 5 years of age were included and who lived in urban and rural areas in three entities of Mexico: Chihuahua, Yucatán and Mexico City. The spectrum of the population included were children with biological or environmental risk factors as well as children without risk for developmental delay. Children with obvious neurological abnormalities were excluded. BDI-2 was used as a gold standard at all sites, although in Mexico City Bayley-III was also used. CDE and BDI-2 tests were applied to each participant on the same day or within a period not exceeding 1 week. The person applying the BDI-2 or Bayley-III was unaware of the result of the CDE. Test rating and data intake were stored at a central location.

For the present study, the results were analyzed based on results of the CDE and with those obtained in each of the domains and subdomains of the BDI-2. TDQ was used for domains whose normal parameters have an average of 100 and a standard deviation (SD) of 15. This value is derived from the sum of the scores obtained for each of the five domains assessed. Similarly, the development quotient (DQ) of each domain is obtained from the sum of the scores for each subdomain.3 Two benchmarks were used: a) TDQ <80, which includes categories of mild retardation (DQ = 70-79) and significant delay (DQ <70). If the result of the TDQ is within these values, 100% have at least one area with a score lower than −1 SD and 78.3% less than −2 SD; b) DQ <90, also includes the category of normal-low (DQ 80-89).Within these values, 23% have at least one area with a score lower than −1 SD and 2.2% less than −2 SD. On the other hand, for the subdomains, Z score was used with a cutoff value <−1.33 SD, which is equivalent to a DQ <80, classifying it within the range of developmental delay because the score for subdomain has an average of 10 (SD = 3). Therefore, for all participants who obtained yellow or red results in the screening test and in the BDI-2, a TDQ greater than or equal to the established cutoff points were considered as “false positives.” These analyses were stratified into two age groups: a) 1 month-15 months, b) 16-59 months.

The study was approved by the Research, Ethics and Biosafety Committees of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez. Parents of all participants gave informed consent.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency, as well as presenting median and interquartile range (IQR) for numeric variables. To evaluate differences between groups, x2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used. Statistical significance was defined as two-tailed p value <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v.19.0 package.

3. Results

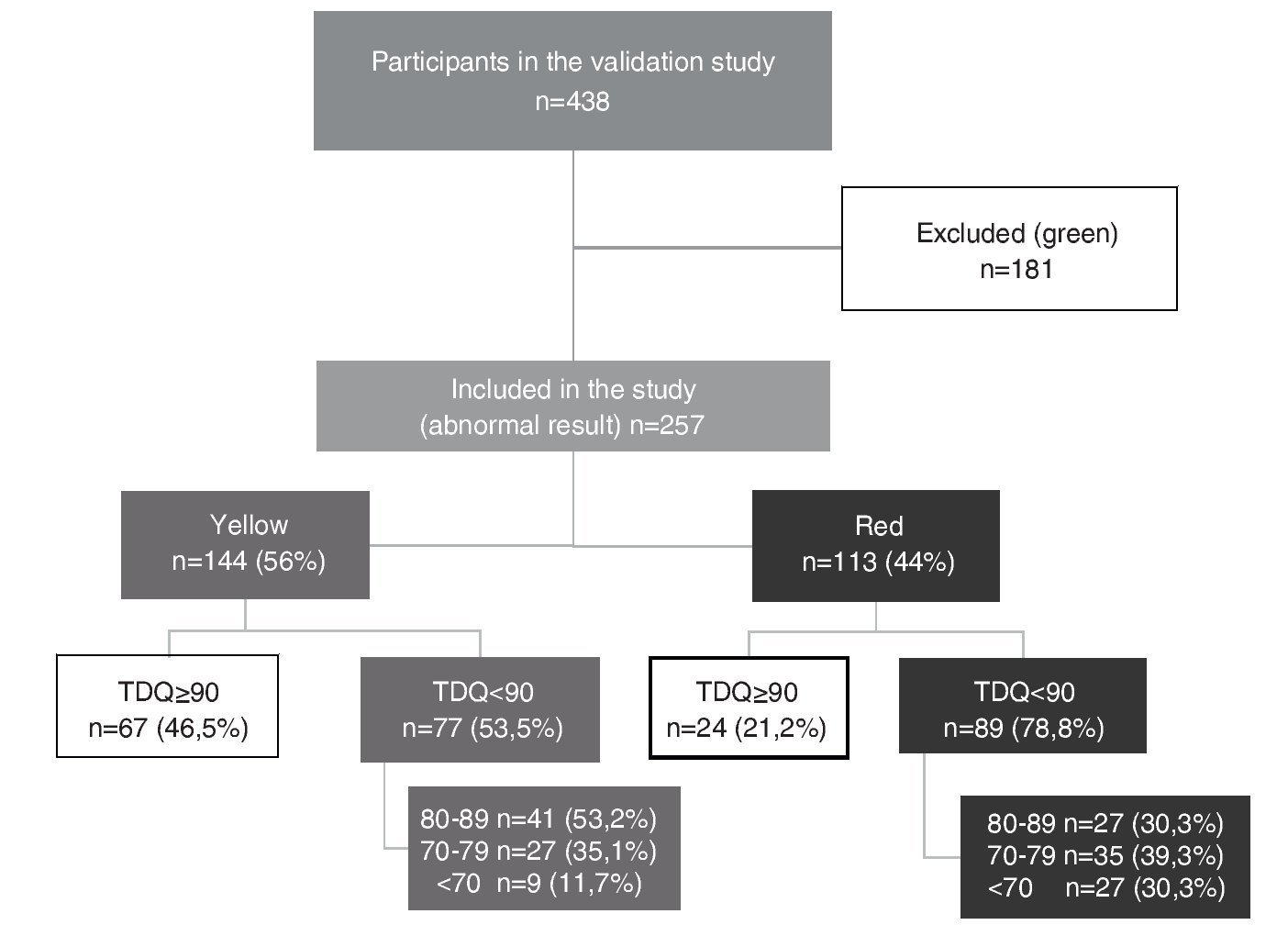

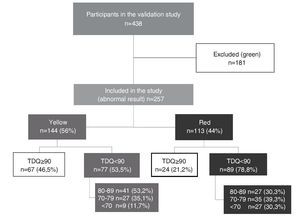

Of the 438 participants in the validation study, 41.3% (n = 181) had a normal result (green) and, therefore, were excluded from this study. Thus, this analysis corresponds to 257 children whose result was abnormal in the CDE (those who were rated yellow or red). Of this total, 56% (n = 144) were yellow or with mild risk for developmental delay, whereas the remaining 44% (n = 113) were red or at high risk for developmental delay.

Median TDQ in children with a yellow result was 88.5 (IQR 67.8-109.3), which was significantly higher (p <0.0001) than the red group: 78 (IQR 60-96). Based on the distribution of the TDQ for the categories of abnormal development (yellow vs. red), the percentage of “false positives” (TDQ ≥90) was 46.5% for those who obtained a yellow result and 21.2% for a red result in the CDE test (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of the study participants according to results of the Child Development Evaluation (CDE) and total development quotient (TDQ) category.

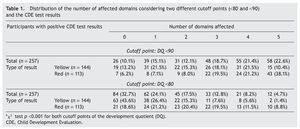

3.1. Number of affected domains

Two cutoff points for DDQ were used in the analysis of the five domains assessed. When considering a DDQ <90 with a yellow result, 86.8% had at least one affected domain and 50% had three or more domains, compared with 93.8% and 78.8%, respectively, of those with a red result. When considering a DDQ <80 (delay and significant delay) resulting in yellow, 56.4% had at least one affected domain and 14.6% three or more domains, compared with 81.4% and 39.8% of those who obtained a red result, respectively (Table 1). The difference of the two proportions was statistically significant (p <0.001).

3.2. Domain analysis

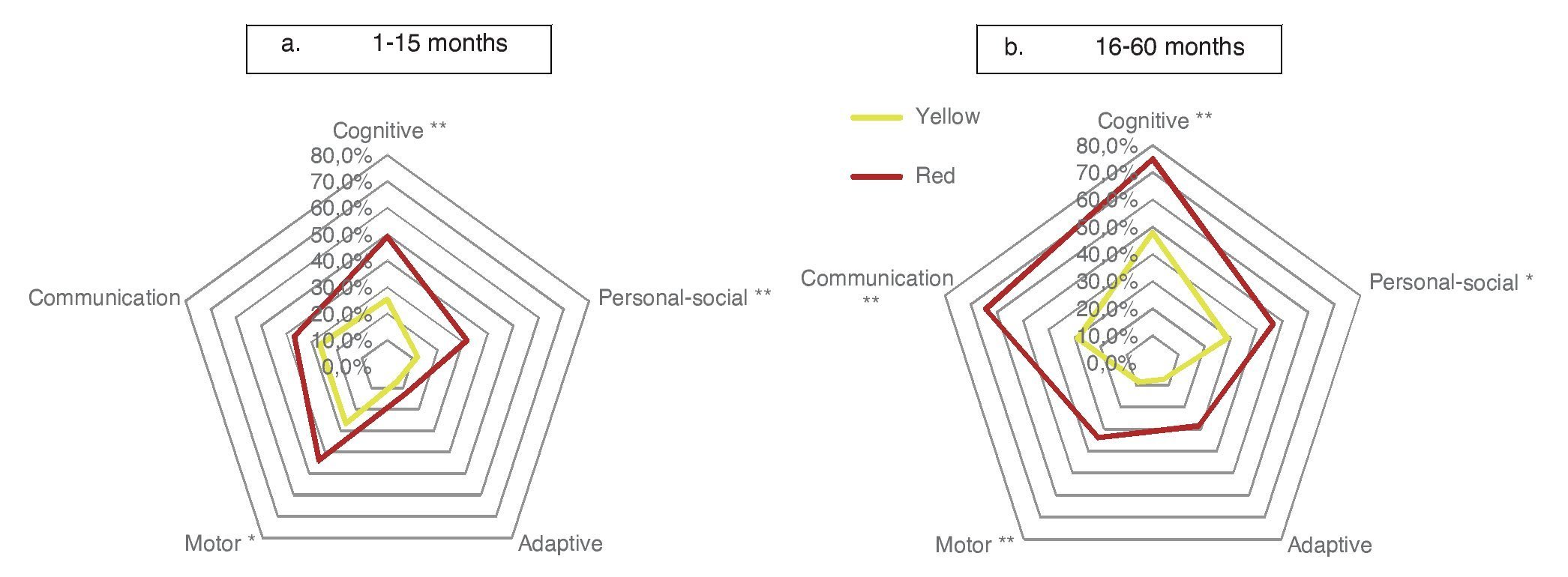

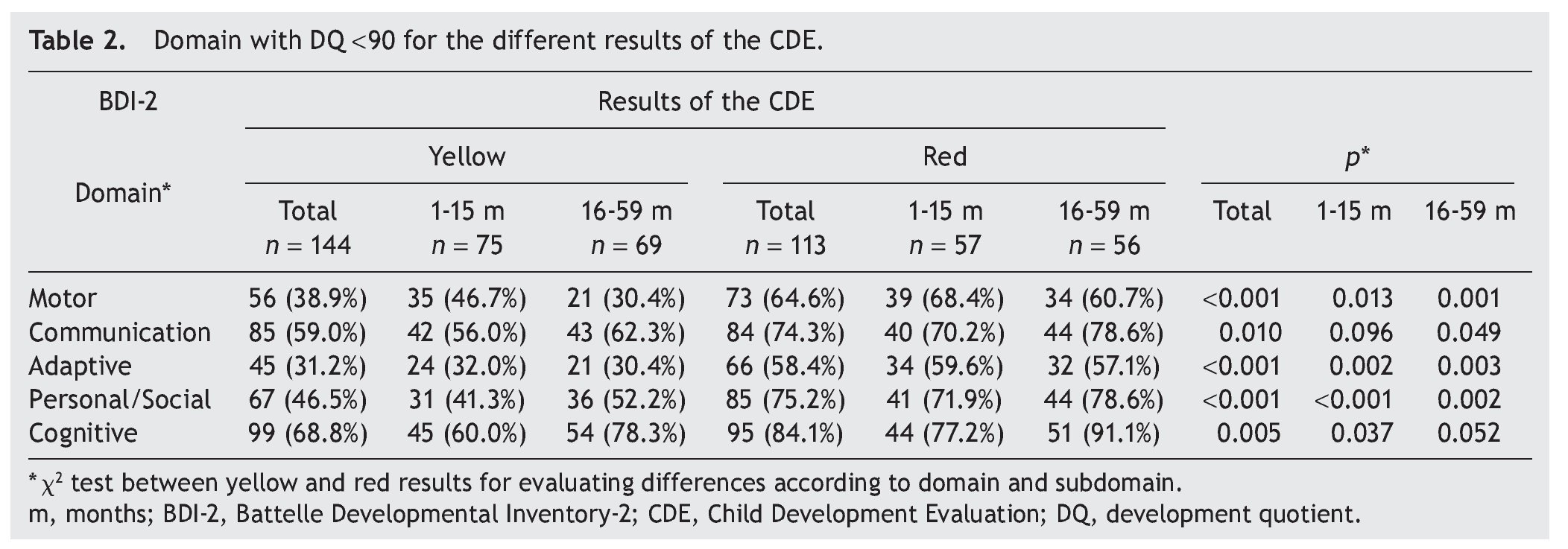

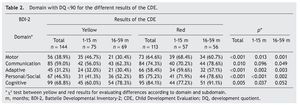

Significant differences were found in the percentage of participants with affected domains (cutoff DDQ <90) among those who obtained yellow and red results: cognitive (68.8% vs. 84.1%); communication (59.0% vs. 74.3%); personal-social (46.5% vs 75.2%); motor (38.9% vs 64.6%); and adaptive (31.2% vs. 58.4%) (Table 2). With the same cutoff in the analysis by age, significant differences between results of the CDE (yellow vs. red) in all areas except in the domain of communication in the subgroup 1-15 months of age were found. In the subgroup of 16-59 months of age, statistically significant differences were found for all domains with the exception of cognition.

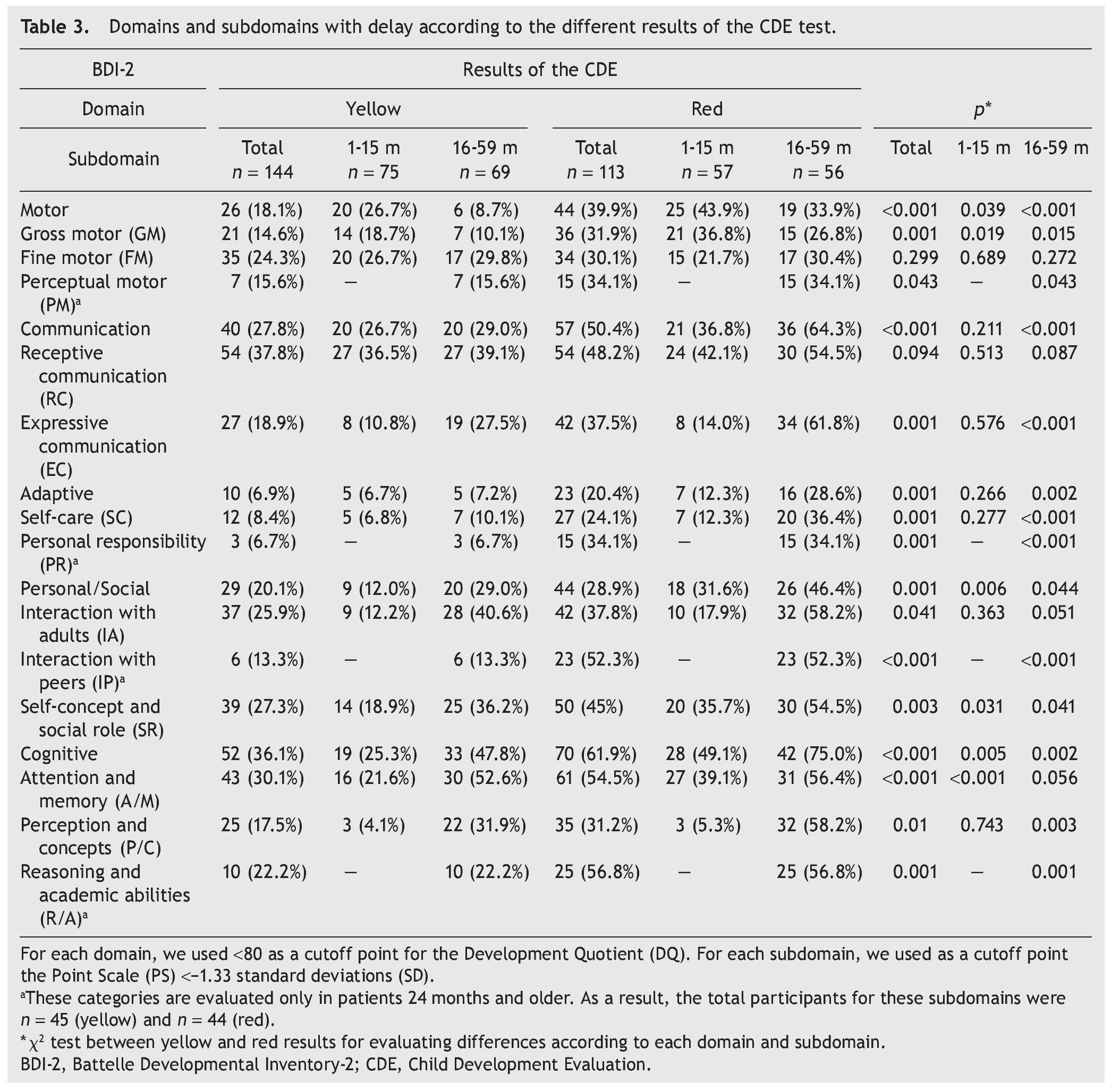

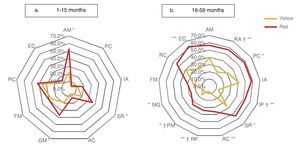

When considering only those domains with delay or significant delay (DDQ <80), it was also observed that the red group had a higher frequency of alterations (Table 3), which was statistically significant (p ≤0.001) for all domains: cognitive (36.1 vs. 61.9%); communication (27.8 vs. 50.4%); motor (18.1 vs. 39.9%); personal-social (20.1 vs. 28.9%); and adaptive (6.9 vs. 20.4%) (Fig. 2). In the subgroup of 1-15 months of age, only significant differences for cognitive, motor and personal-social domains were observed; meanwhile, in the subgroup of 16-59 months of age the differences were significant for all domains.

Figure 2 Percentage of children according to domain affected (domain quotient, DQ <80) and age group comparing the result with the CDE.

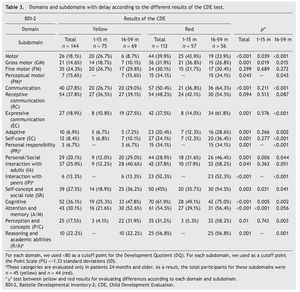

3.3. Subdomain analysis

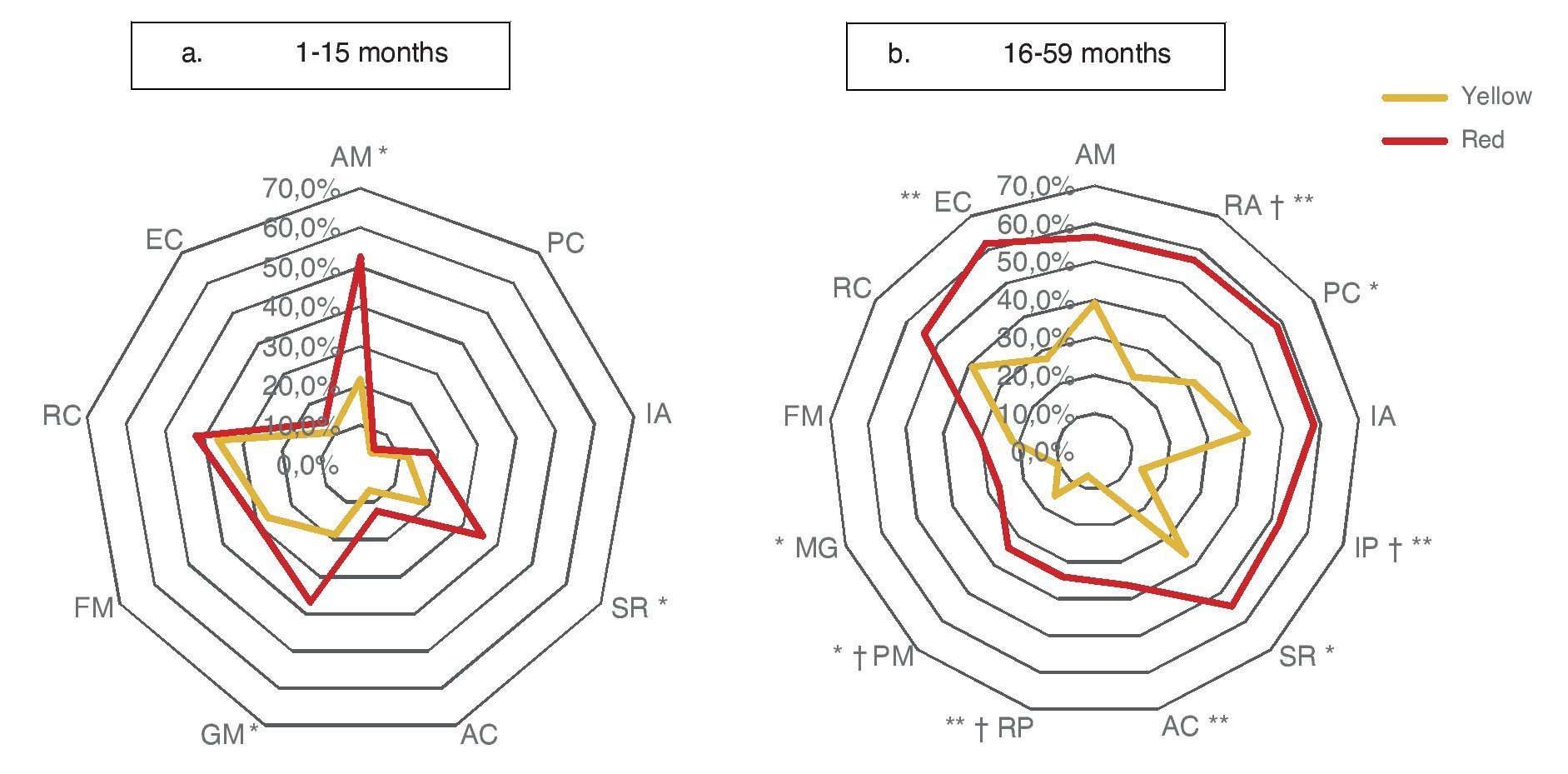

Significant differences (p ≤0.05) among participants with red vs. yellow for all subdomains except receptive communication and fine motor skills (Table 3) were found. In the subgroup of children 16-59 months of age, significant differences were found (p ≤0.05) between yellow and red results in all subdomains except receptive communication, fine motor skills, attention and memory.

Significant differences observed between yellow and red results in cognitive (25.3 vs. 49.1%), personal-social (12.0 vs. 31.6%) and motor domains (26.7 vs. 43.9%) may be explained by the percentages of involvement and were presented for specific subdomains: attention and memory (21.6 vs. 39.1%) for the cognitive domain; self-perception and social role (18.9 vs. 35.7%) for the personal-social domain; and gross motor skills (18.7 vs. 36.8%) for the motor domain. In children >16 months of age with results in yellow and red, there are significant differences in all domains and subdomains except attention and memory, adult interaction, fine motor skills and receptive communication (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Percentage of children according to the affected evaluated subdomain* (Battelle Developmental Inventory, BDI-2) and age group, comparing the result with the CDE.

4. Discussion

This study shows, in greater depth, that the proposal to indicate a “traffic light” ranking (green, yellow, and red) after applying the CDE in children <5 years of age is appropriate. Thus, it can be confirmed that failure to obtain a normal result (green) in the screening test strongly suggests that the child has some degree of impaired development. In particular, results of this study show how children classified as yellow have a lower degree of neurodevelopmental delay than cases classified as red, supporting differentiated interventions. However, discrimination is not as clear when it is analyzed by domain, especially in communication and cognition.

As shown in Table 1, 86.8% of children with yellow results and 93.8% of children with red results have at least one domain with a DDQ <90 and may benefit from an intervention to promote healthy development. Depending on the results, possible interventions require a different magnitude because 78.8% of the children were identified with a red result in three or more domains with DDQ <90 (low-normal to severe delay) and 81.4% in at least one domain within significant delay (DDQ <80) compared with 50% and 56.3% for children with a yellow result, respectively.

Furthermore, it would be convenient to consider that the possible explanations for the CDE cannot discriminate between yellow and red in the attention and memory subdomains. According to the BDI-2,7 children <18 months of age are focused on evaluating visual tracking, anticipatory behavior (perceive that someone is approaching), audio tracking and paying attention to sounds. Test items of self-concept and social role (SR) subdomain8 in this same group evaluate the response to interaction with adults and expression of emotions. In order to do this, as was the case for the attention and memory subdomain, it is necessary that the child be able to see and hear properly; therefore, a delay in these subdomains can be directly associated with visual or hearing impairments. Therefore, when a child is classified with a yellow result, initially it may be sufficient to provide counseling in order to encourage visual and auditory monitoring behaviors and promote anticipatory behaviors, whereas identification of children with a red result should help in making a timely referral for assessment by a specialist. Because children classified with a red result have a higher frequency of delay in attention and memory subdomains (Table 3), it would be easier to recommend a pediatric evaluation to rule out visual or hearing impairments. As stated in NOM-015-SSA3-2012,9 diagnosis of congenital abnormalities that lead to hearing impairment must be conducted within 3 months of age and preferably by an audiologist, but also early detection of visual impairment and early stimulation in case of congenital visual impairment.

Assessment of gross motor subdomain10 during this period includes head control, limb movement, sitting, crawling, standing and walking. In case of delay, it is essential to establish a specialized neurological diagnosis (e.g., quadriplegia or hemiplegia). Because one of the evaluations of the neurological examination is asymmetry in body movements and questions related to this domain are included in the warning signs, children classified as yellow and with a delay in this domain could improve with maternal recommendations for performing massage and exercise to improve muscle tone and encourage motor skills. However, if the child persists with a yellow result in both assessments (6 months), then he/she should be considered as having a red result and be referred to a specialist for evaluation.1

In the analysis by subdomains in the age group of 16-59 months, the highest prevalence of delay was observed (>50%) in children with a red result in the CDE in attention and memory, reasoning and academic skills, perceptions and concepts, interaction with peers, interaction with adults as well as self-perception, social role and expressive communication. This finding underscores the need for the application of a test to evaluate more accurately each of the neurodevelopmental aspects, such as the BDI-2. Thus, we would have the ability to identify the problem or problems in some of these subdomains and establish an individual counseling for each case where parenting practices or actions needed could be strengthened so that children receive an enriched environment, thereby improving their development.

In addition to considering the potential impact of the individual clinical outcome of the implementation of CDE, it is necessary to note that detection of neurodevelopmental problems at the population level may result in implications for the health system or for the family. For example, due to what has been reported in the present study, the fact that the classification in yellow and red identifies children with minor and major developmental delays, respectively, is favorable in some situations because patients will be referred to different specialists (to the pediatrician, in the case of a yellow result and to the psychologist for applying neurodevelopmental confirmatory tests in the case of a red result) avoiding overload of services and subsequent evaluations. However, implementation of the CDE nationwide involves having available at the community, state and jurisdictional level a reference and counter-reference system effective for children identified with disorders so they can receive appropriate and timely medical care, both to establish the diagnosis and to provide, where appropriate, the corresponding treatment. This implies, among other things, the need for health services to have sufficient and qualified staff in each of the levels of health care.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the results of this study should be taken with caution and under limitations. Data presented do not come from a nationally representative population <5 years of age. Once further details of the implementation of the CDE are available, we will be able to verify whether what is described in this analysis is reproducible. One of these limitations is related to the result of the high prevalence (total number of children classified as yellow and red) detected of neurodevelopmental disorders (58.6%) in the 458 cases analyzed. This ratio will certainly be lower when the CDE is applied at the population level, and it can also be established with greater certainty the reliability of CDE results with different subdomains of BDI-2.11 Another limitation is the cross-sectional design of this study; therefore, it is still unknown what will happen when evaluations are conducted in accordance with the CDE as children grow or when interventions occur in cases classified with a yellow result. It is also required to know the causes or diagnoses of cases classified with a red result.12

In conclusion, results obtained in the present study using a “traffic light” ranking for children <5 years of age with developmental disorders and classified as a yellow or red result when applying the CDE allow us to identify children with different magnitudes of developmental delay. This may contribute to the provision of different interventions applied immediately after the test. However, to determine with strength the ability of the CDE to identify children with neurodevelopmental disorders, it is necessary to increase the number of children in whom this test was applied and to compare the results with the reference standard.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of Data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Funding

This study was carried out with funding provided by Convenio CPSS/ART.1°/128/2011 through Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez and the Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud (CNPSS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Acknowledgments

Joaquín Carrasco Mendoza, Fátima Adriana Antillón Ocampo, Hortensia Reyes Morales, Elías Hernández Ramírez, Ana Alicia Jiménez Burgos, Marta LiaPirola, Rocío del Carmen Córdoba García, María Esther Valadez Correa, Jorge Carreón García, Víctor Hugo López Aranda, Iván Rivas Rodríguez, Caridad Araujo, Ricardo Pérez Cuevas, Olga Susana Lira Guerra, Edgar Flores Pérez, Heidi de Lourdes Río Hoyos, Roberto Robles Anaya and Amalia Reyes Peón.

Received 23 July 2014;

accepted 8 October 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: antoniorizzoli@gmail.com (A. Rizzoli-Córdoba).