Identification of nonfermenting Gram-negative bacteria (NFGNB) of cystic fibrosis patients is hard and misidentification could affect clinical outcome. This study aimed to propose a scheme using polymerase chain reaction to identify NFGNB. This scheme leads to reliable identification within 3 days in an economically viable manner when compared to other methods.

Chronic respiratory tract infection is responsible for high morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients and is frequently associated with nonfermenting Gram-negative bacteria (NFGNB).1 The microbiology of CF lung disease has changed substantially in recent decades, and now includes novel NFGNB such as Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc), Achromobacter xylosoxidans and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, as well as several species of Ralstonia, Cupriavidus and Pandoraea.1,2 Most exhibit high resistance to antimicrobials, which makes treatment problematic, and have the potential for interpatient transmission, leading some healthcare facilities to strongly recommend patient segregation.1,3,4

Chronic infections, especially by Bcc species, may result in accelerated decline of pulmonary function.5 This complex comprises at least 20 species, and although most are potentially capable of causing infections, Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia multivorans are considered the most prevalent, and B. cenocepacia is related to highly transmissible and virulent clonal lineages.6 Some are associated with cepacia syndrome, a necrotizing pneumonia that leads to rapid deterioration of lung function, bacteremia and increased mortality.5,7,8A. xylosoxidans, which is considered the most common species within the genus Achromobacter, has been shown to cause a level of inflammation similar to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronically infected CF patients and a greater decline in lung function in these patients compared to non-infected patients.9 Chronic pulmonary infection with S. maltophilia has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of pulmonary exacerbations, which leads to increased risk of lung transplantation or death in individuals with CF.10 The large number of pili/fimbriae synthesized by S. maltophilia, which are associated with adhesion and biofilm formation, may contribute to the maintenance of this bacteria in lung infections, which shows why this microorganism is persistent and difficult to eradicate.11 Since the consequence of these pathogens in the CF lung can be very serious, their correct identification is extremely important for a more efficient treatment.

Due to taxonomic complexity and high phenotypic similarity between these NFGNB, accurate identification represents a challenge for conventional microbiology. Conventional phenotypic methods including observation of colony morphology on media, analysis of manual biochemical reactions, and the use of automated and nonautomated commercially available biochemical panels are not suitable for CF isolates identification. NFGNB often present colonies of atypical appearance and lack key metabolic characteristics, which impairs the identification.12,13 Automated systems, as Vitek® 2 (bioMérieux), lead to inaccurate identification of NFGNB due to their phenotypic variations and slower growth rates.14 Moreover, commercial phenotypic databases are often outdated and lack current taxonomy.12 Misidentification of NFGNB seriously compromises infection control measures and confounds efforts to more clearly understand the epidemiology and natural history of infection in CF.4,15

Currently, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) is used in clinical microbiology laboratories for identification of CF bacterial species. It presents low cost per sample, and is considered to be a faster, and more reliable alternative than polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for these microorganisms identification.15 However, the high cost of the equipment may be considered a limitation for some laboratories.16 In addition, many recent studies report difficulty in identifying microorganisms at the species level, due to great variations of protein spectra in different strains belonging to the same species.17–19

PCR is considered a simple and highly sensitive technique that produces results quickly, and it is economically viable when compared to sequencing methods.20 The objective of the present study was to propose a scheme using PCR to identify NFGNB, based on the results of identification of reference strains and clinical isolates from CF patients.

The following reference strains were used in this study: A. denitrificans LMG 1231, A. piechaudii LMG 1873, A. xylosoxidans LMG 1863, A. dolens LMG, A. insuavis, A. mucicolens, A. ruhlandii, C. gillardi LMG 5886, P. norimbergensis LMG 18379, P. pnomenusa LMG 18087, P. pulmonicula LMG 18106, P. apista LMG 16407, R. picketti LMG 5942, S. maltophilia LMG 958, B. cepacia 1254, B. multivorans 788, B. cenocepacia LMG 21462, B. cenocepacia 818 Genomovar IIIA, B. cenocepacia 17604 Genomovar IIIA, B. cenocepacia 842 Genomovar IIIB, B. cenocepacia 805 Genomovar IIIB, B. stabilis 790, B. stabilis 825, B. vietnamiensis LMG 10929, B. vietnamiensis 1109, B. dolosa LMG-18943, B. ambifaria LMG 19182, B. ambifaria ATCC-53266, B. ambifaria AMMD, B. anthina LMG-20980, B. anthina LMG-16670, B. pyrrocinia ATCC-39227 and B. pyrrocinia LMG-14191. All of them were tested with each pair of primers shown in Table 1 in order to evaluate the specificity of PCR assays.

PCR conditions used in the present study.

| PrimerTarget | Primers | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp)a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. cepacia(Genomovar I) | BCRG11BCRG12 | 62 | 492 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. multivorans(Genomovar II) | BCRBM1BCRBM2 | 62 | 714 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. cenocepacia(Genomovar III-A) | BCRG3A1BCRG3A2 | 62 | 378 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. cenocepacia(Genomovar III-B) | BCRG3B1BCRG3B2 | 60 | 781 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. stabilis(Genomovar IV) | BCRG41BCRG42 | 64 | 647 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. vietnamiensis(Genomovar V) | BCRBV1BCRBV2 | 62 | 378 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| B. dolosa(Genomovar VI) | G6NBCR1 | 67 | 135 | Vermis et al.23 |

| B. ambifaria(genomovar VII) | BCRGC1BCRGC2 | 62 | 810 | Coenye et al.24 |

| B. anthina(genomovar VIII) | BCRG81BCRG82 | 61 | 473 | Vandamme et al.25 |

| Complexo B. cepacia – Gene recA | BCR1BCR2 | 58 | 1043 | Mahenthiralingam et al.22 |

| A. xylosoxidans | AX-F1AX-B1 | 56 | 163 | Liu et al.26 |

| S. maltophilia | SM1SM4 | 58 | 531 | Whitby et al.27 |

| P. sputorum | spuFspur | 63 | 813 | Coenye et al.28 |

| GenusRalstonia | RalGS-FRalGS-R | 58 | 546 | Coenye et al.29 |

| GenusCupriavidus | ral2fral2r | 58–61 | 187 | Barrett and Parker30 |

The extraction of genomic DNA was performed using the method described by Gianni-Rossolini.21 PCR was conducted in a volume of 25μL adding 2.5μL of 10× concentrated PCR buffer solution, 2mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 0.625U Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), 0.2mM each of the 4 nucleotides (dNTP – Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), 20pmol of the primers for amplification of genes, 60ng of DNA and ultrapure water (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Amplification was carried out with the Mastercycler Gradient Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Cycling conditions for amplification were used according to the referenced articles (Table 1).

PCR was first performed according to Table 1. Modifications were proposed when nonspecific reactions were obtained or products were not amplified for the purpose of each primer (Table 2).

Comparison of the primers and genus/species proposed by the literature and proposed by the present study.

| Primers | Genus/speciesTargets | Proposed modificationsa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | The present study | ||

| BCR1/BCR2 | Bcc bacteria | Bcc bacteria | AT 55°C and 56°C |

| AX-F1/AX-B1 | A. xylodoxidans | Achromobacter sp. | NMT |

| SM-1/SM4 | S. maltophilia | S. maltophilia | NMT |

| spuF/spuR | P. sputorum | Pandoraea sp.+Ralstonia sp. | NMT |

| RalGS-F/RalGS-R | Ralstonia sp. | Ralstonia sp.+Cupriavidus sp. | NMT |

| ral2f/ral2r | Cupriavidus sp. | Cupriavidus sp.+Ralstonia sp.+Pandoraea sp.+Achromobacter sp. | AT 62°C |

This study included 201 clinical isolates of NFGNB previously identified by the Vitek® 2 Compact system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). The isolates were obtained from July 2011 to September 2014 from patients with CF who were treated at two locations: 44 patients from Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto – Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMRP-USP), and 56 patients from Hospital de Clínicas da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas – Universidade Estadual de Campinas (HCFCM-UNICAMP). The study was approved by the Committee on Ethical Practice of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo by number 210, with agreement by the Clinical Hospital of the Ribeirão Preto Medical School of the University of São Paulo and the Clinical Hospital of the School of Medical Sciences of the State University of Campinas. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The following tests were carried out for screening of the NFGNB isolates: macroscopic characteristics in Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep's blood, MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) and B. cepacia Selective Agar (BCSA – Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK); Gram morphology; oxidation/fermentation of glucose and xylose (Difco, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA); and production of oxidase, as previously described.31

Identification of clinical isolates was performed by PCR using primers of genus/species according to proposed modifications by this study (Table 2). All clinical isolates identified as belonging to Bcc were selected to perform restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (PCR-RFLP) in order to identify the species of Bcc. Amplicons generated by PCR using the primers BCR1 and BCR2 were digested with HaeIII restriction endonuclease in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).32 Generated restriction fragments were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%). Molecular size markers were used (100bp ladder, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized and photographed with the AlphaImager System® (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, California, USA). All reference strains of Bcc were used as positive controls.

PCRs carried out for primers as shown in Table 2 allowed the recognition only of the genus for most NFGNB, except for primer pair SM-1/SM-4, which was specific to the genus and species for S. maltophilia.

Primers BCR1/BCR2 and SM-1/SM-4, used to identify Bcc isolates and S. maltophilia, respectively, generated amplicons of the expected size and showed high specificity and sensitivity. Primers BCR1/BCR2 showed positive results not only for B. cepacia, B. multivorans, B. cenocepacia IIIA and IIIB, B. stabilis and B. vietnamiensis as presented by Mahenthiralingam et al.,22 but also for B. dolosa, B. ambifaria, B. anthina, and B. pyrrocinia (Table 3).

Results of amplification of all NFGNB using proposed modifications.

| Bacteria tested | Genus/speciesPrimers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BccBCR1/BCR2 | P. sputorumspuF/spuR | Ralstonia sp.RalGS-F/RalGS-R | A. xylosoxidansAX-F1/AX-B1 | S. maltophiliaSM-1/SM4 | Cupriavidus sp.ral2f/ral2r | |

| Reference strains | ||||||

| A. denitrificans LMG 1231 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. piechaudii LMG 1873 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. xylosoxidans LMG 1863 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. dolens LMG | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. insuavis | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. mucicolens | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| A. ruhlandii | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| C. gillardi LMG 5886 | Negative | Negative | Positivea | Negative | Negative | Positive |

| P. norimbergensis LMG 18379 | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| P. pnomenusa LMG 18087 | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| P. pulmonicula LMG 18106 | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| P. apista LMG 16407 | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| R. picketti LMG 5942 | Negative | Positivea | Positive | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| S. maltophilia LMG 958 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| B. cepacia 1254 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. multivorans 788 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. cenocepacia LMG 21462 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. cenocepacia 818 Gen. IIIA | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. cenocepacia 17604 Gen. IIIA | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. cenocepacia 842 Gen. IIIB | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. cenocepacia 805 Gen. IIIB | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. stabilis 790 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. stabilis 825 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. vietnamiensis LMG 10929 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. vietnamiensis 1109 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. dolosa LMG-18943 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. ambifaria LMG 19182 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. ambifaria ATCC-53266 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. ambifaria AMMD | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. anthina LMG-20980 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. anthina LMG-16670 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. pyrrocinia ATCC-39227 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| B. pyrrocinia LMG-14191 | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Isolates | ||||||

| Bcc (n=91) | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Achromobacter sp. (n=85) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positivea |

| S. maltophilia (n=12) | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Ralstonia sp. (n=10) | Negative | Positivea | Positive | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| Pandoraea sp. (n=2) | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positivea |

| Cupriavidus sp. (n=1) | Negative | Negative | Positivea | Negative | Negative | Positive |

According to Liu et al.,26 the primer pair used to identify A. xylosoxidans (AX-F1/AX-B1) showed 97% specificity. In this study, this primer pair generated amplicons only for Achromobacter genus. However, it generated amplicons for A. xylosoxidans, and for all isolates of A. piechaudii, A. denitrificans, A. dolens, A. insuavis, A. mucicolens, and A. ruhlandii (Table 3).

According to Coenye et al.,28 the primer pair spuF/spuR was effective for identification of P. sputorum and genomospecies 2 and 3. In the present study, these primers generated amplicons for all species of Pandoraea tested, but they also generated amplicons for Ralstonia sp. The primer pair RalGS-F/RalGS-R provided amplicons for Ralstonia sp., but they also generated amplicons for Cupriavidus sp. The primer pair ral2f/ral2r, which is specific for Cupriavidus, also provided amplicons for three other bacteria genera: Achromobacter, Pandoraea and Ralstonia (Table 3). It was necessary to perform PCR using both primer pairs spuF/SpuR and RalGS-F/RalGS-R to allow identification of these microorganisms. If both primer pairs generate amplicons, the isolate should be identified as belonging to the genus Ralstonia. If there are amplicons only with the pair of primers spuF/spuR, the isolate should be identified as belonging to the Pandoraea genus. If after conducting PCR for the genera Pandoraea and Ralstonia, only amplicons from the primer pair RalGS-F/RalGS-R are generated, the Cupriavidus genus is suspected. Therefore, it is also necessary to obtain amplicons with primer pair ral2f/ral2r to confirm the identification as Cupriavidus.

Amplification with specific primers for bacterial species from Bcc did not produce nonspecific reactions to other bacterial genera that were not from Bcc. Primers used to identify the genomovars B. cenocepacia (III-A), B. cenocepacia (III-B), B. stabilis (IV), B. dolosa (VI) and B. anthina (VIII) generated amplicons of the expected size with high specificity. However, the primers used for identification of B. anthina (VIII) provided amplicons for strain B. anthina (VIII BC LMG-16670), but not B. anthina (VII BC AMMD). The primer pairs recommended for identification of B. cepacia (I), B. multivorans (II) and B. vietnamiensis (V) allowed amplification of fragments of the same size as other standard strains, different from what was expected: primers BCRG11/BCRG12 were considered effective for identification of B. cepacia, but also provided amplicons for B. cenocepacia (IIIA, 818 BC), B. pyrrocinia (IX, ATCC 39227) and B. pyrrocinia (LMG 14191); primers BCRBM1/BCRBM2 were considered effective for identification of B. multivorans (II, 788 BC) but also produced amplicons for B. cenocepacia (IIIB, 842 BC) and B. stabilis (IV BC 790); and primers BCRBV1/BCRBV2 were considered effective for the identification of B. vietnamiensis (V BC 1109) but also produced amplicons for B. multivorans (II, 788 BC), B. cenocepacia (IIIB, 842 BC), B. stabilis (IV, 790 BC), B. anthina (VIII BC 16670) and B. pyrrocinia (IX, BC 39227). The primer pair recommended for B. ambifaria (VII) did not work at any annealing temperature (data not shown).

All PCRs were repeated at least five times to ensure reproducibility under the conditions described by the authors (Table 1) and under the proposed conditions for annealing temperature (Table 2).

Analysis of PCR-RFLP patterns generated by digestion with the restriction enzyme HaeIII was able to discriminate all genomovars, except genomovars I and IIIA, which were differentiated by PCR. This analysis was also able to differentiate subgroups IIIA and IIIB of B. cenocepacia. Due to the high cost of sequencing, PCR-RFLP may be considered an option for clinical laboratories, especially because of its ability to identify the species B. multivorans and B. cenocepacia, which are linked to worse clinical prognoses than other species.4

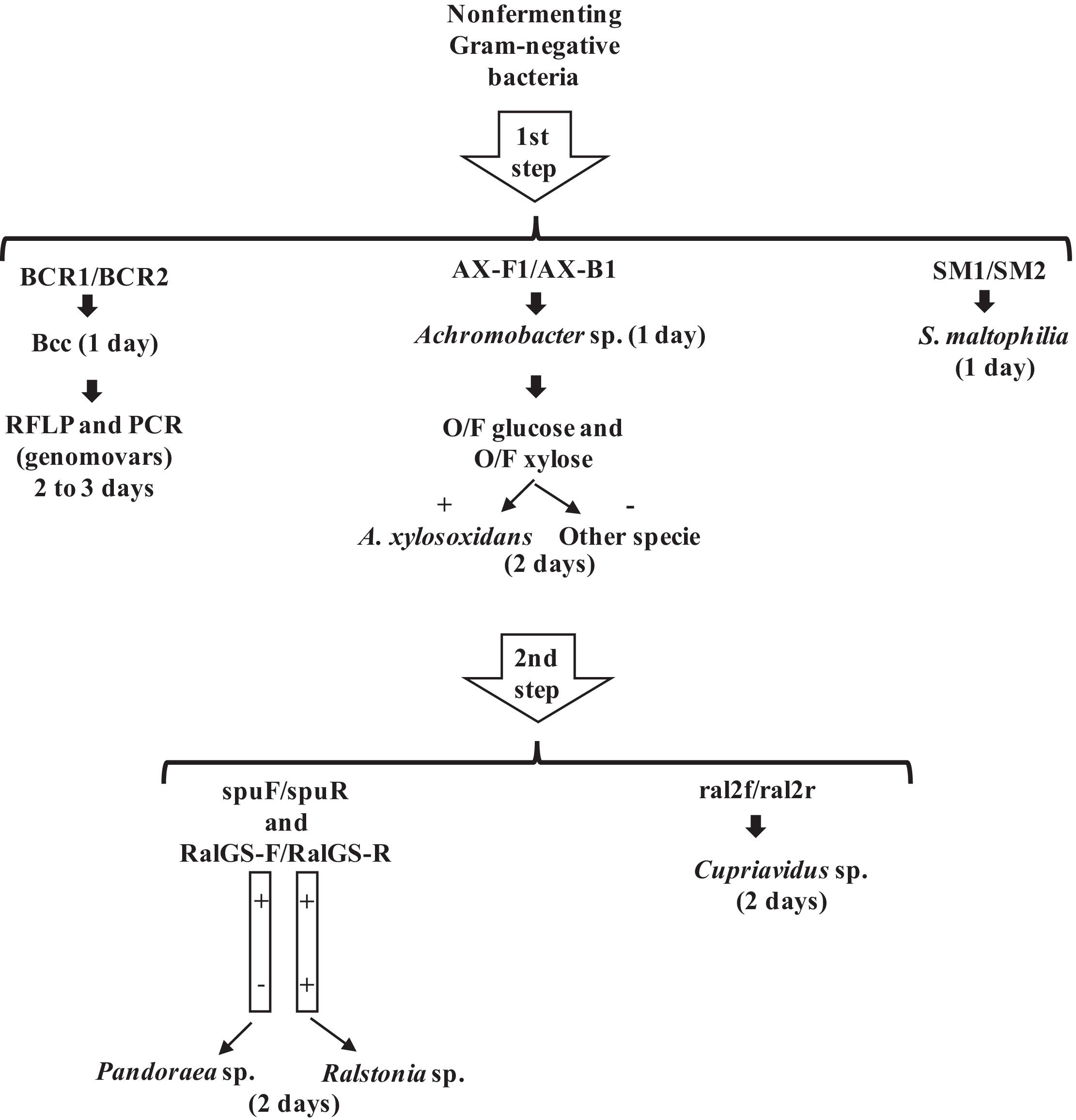

Based on the results of the identification of reference strains and clinical isolates, the present study proposed a PCR scheme for identification of emerging NFGNB isolated from CF patients (Fig. 1). The proposed scheme suggested that the first primers to be tested must have the highest specificity and first target the most frequent NFGNB with greater clinical impact.

The first step proposed was using the primer pairs BCR1/BCR2, AX-F1/AX-F2 and SM1/SM2 for Bcc, Achromobacter sp. and S. maltophilia, respectively. Within a shorter time frame compared with traditional tests, this approach allows the adoption of a segregation policy for individuals infected with Bcc. When amplification for Bcc occurs, PCR-RFLP and PCR with the primers BCRG3A1/BCRG3A2, which is used to identify B. cenocepacia (IIIA), should be performed to identify Bcc genomovars, since only PCR-RFLP was not able to discriminate B. cepacia from B. cenocepacia (IIIA).

The second step proposed was using the primer pairs spuF/spuR, RalGS-F/RalGSR and ral2f/ral2r to differentiate Pandoraea, Ralstonia and Cupriavidus, which were effectively identified by this scheme.

This scheme leads to reliable identification of all these microorganisms within three days, and this rapid identification allows for early antibacterial therapy and segregation. Comparative outcome studies are needed before conclusions about the relative virulence of specific strains can be drawn, and the first step is accurate identification in the laboratory. Furthermore, this scheme is more economically viable when compared to other methods based on sequencing. Therefore, this scheme can provide early bacterial diagnosis in CF patients, which can assist in increasing life expectancy.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We wish to thank Joseane Cristina Ferreira and Rubens Eduardo Silva for technical assistance. We would like to thank Roberto Martinez and the Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto for bacterial isolates. This work was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP2014/14494-8), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq473053/2012-8), and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel program (CAPES). We also thank the Departamento de Microbiologia e Imunologia of Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro and the Departamento de Patologia Clínica of Faculdade de Ciências Médicas of Universidade de Campinas for all reference strains.