We surveyed healthy captive cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) for Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. Cloacal swabs were collected from 94 cockatiels kept in commercial breeders, private residencies and pet shops in the cities of São Paulo/SP and Niterói/RJ (Brazil). Three strains of E. coli from each individual were tested for the presence of ExPEC-, APEC- and DEC-related genes. We evaluated the blaTEM, blaSHV, blaOXA, blaCMY, blaCTX-M, tetA, tetB, aadA, aphA, strAB, sul1, sul2, sul3, qnrA, qnrD, qnrB, qnrS, oqxAB, aac (6)′-Ib-cr, qepA resistance genes and markers for plasmid incompatibility groups. Salmonella spp. was not detected. E. coli was isolated in 10% of the animals (9/94). Four APEC genes (ironN, ompT, iss and hlyF) were detected in two strains (2/27–7%), and iss (1/27–4%) in one isolate. The highest resistance rates were observed with amoxicillin (22/27–82%), ampicillin (21/27–79%), streptomycin (18/27–67%), tetracycline (11/27–41%). Multiresistance was verified in 59% (16/27) of the isolates. We detected strAB, blaTEM, tetA, tetB, aadA, aphaA, sul1, sul2, sul3 resistance genes and plasmid Inc groups in 20 (74%) of the strains. E. coli isolated from these cockatiels are of epidemiological importance, since these pets could transmit pathogenic and multiresistant microorganisms to humans and other animals.

Keeping pets is associated with physical and emotional benefits due to its positive effect on people's life quality; however, it may present a risk to public health.1,2 This is because the relationship between men and animals enables transmission of several diseases through pathogens’ ability to colonize several hosts.3 Therefore, pet birds such as cockatiels may harbor and transmit zoonotic agents through close contact with their owners.1,4,5

Salmonellosis, a disease caused by bacteria of the Salmonella genus, has great relevance due to its lethality and zoonotic potential.6 Infected domestic chickens are considered the most common source of human salmonellosis; contaminated chicken meat and eggs are one of the main causes of food poisoning worldwide.6 Furthermore, wild and exotic avian species are also considered Salmonella reservoirs.7

Escherichia coli is a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiome of homeothermic animals. However, pathogenic strains are capable of causing intestinal and extraintestinal diseases in humans, and mammal and avian species, leading to serious economic losses and public health issues.1,5,8

Aside from the zoonotic potential of these enterobacteriaceae, concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance are currently on the rise.8,9 Broad use of antimicrobial drugs, either to treat diseases or in livestock production, resulted in selective pressure and the consequent appearance of multiresistant bacterial strains.10

Antimicrobial resistant enterobacteria may be transmitted to humans through animal contact, contaminated food or the environment.5,10 After colonizing new hosts, they may transfer resistance genes to microorganisms of the local microbiota. Antimicrobial resistance genes may then recombine among these strains, creating new ones resistant to several drugs.5,10

Despite the great global concern with microbial resistances, there is little information available on the epidemiological role of pet birds in the epidemiology of E. coli and Salmonella spp.6 Recent studies in Brazil showed that free-ranging wild birds may harbor potentially pathogenic and antimicrobial resistant strains.11

The aim of this study was to survey cloacal samples of captive cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) for potentially pathogenic Salmonella spp. and E. coli. We also evaluated the antimicrobial resistance profile of the isolates, as well as resistance genes belonging to the main antimicrobial classes.

Materials and methodsAll animal procedures followed ethical principles and were approved by the Ethical Committee in Animal Use (237/14 CEUA/UNIP).

We collected samples from 94 clinically healthy male and female cockatiels (N. hollandicus) kept in captivity: 8 from a pet shop, 28 from different private residencies and 58 from commercial breeders located in the cities of São Paulo and Niterói, in the States of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), respectively.

Upon physical restraining and after pericloacal asepsis with 70% alcoholic solution, two uretral swabs were rubbed against the cloacal mucosa, kept in refrigerated Stuart media and processed within 48h.

Cloacal swab samples for E. coli screening were seeded in MacConkey agar (Difco™, Maryland, EUA) and identified following routine biochemical identification,12 including EPM, MILi and citrate (Probac™, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) identification kits. Three different E. coli isolates from each animal were stored for the remaining tests.

Swabs for Salmonella testing followed the protocol suggested by Michael et al., 2003.13 The swabs were cultivated in buffered peptone water at 37°C by 24h. Aliquots of 1ml were subcultured in 9ml of tetrathionate Müller–Kauffmann (TMK, Difco™, Maryland, EUA). After 24h of incubation, aliquots of the selective broths were streaked onto xylose-lysine-tergitol 4 agar (XLT4, Difco™, Maryland, EUA). After 24h of incubation (37°C), typical colonies of Salmonella were isolated and subjected to biochemical identification.13

We performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on the E. coli isolates in search of extraintestinal pathogenic strains (ExPEC) characteristic genes by accessing genes papC,14papEF,15sfa,14fyuA,16cnf1,15hlyA,15cvaC,16 and malX,16 aside from five avian virulence predicting genes: ironN,17ompT,17hlyF,17iss,17 and iutA.17 The following diarrheagenic-related genes were also studied: stx1,18stx2,18 ST,19 LT,19astA,20ipaH,21aggR,22eae23, and bfpA.24 All E. coli isolates were submitted to the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ-RJ), a reference laboratory, to be tested with O157 and H7 antisera.

Drug sensitivity was evaluated by diffusing plates, following international established standards.25,26 The used drugs (Cefar™, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) belong to the following antimicrobial categories: β-lactams – penicillin (amoxicillin – AMO and ampicillin – AMP), β-lactams – cephalosporins (cephalexin – CFE, cefoxitin – CFO and ceftiofur – CTF) and β-lactams – thienamycin (imipenem – IPM); aminoglycosides (streptomycin – EST and gentamicin – GEN); tetracyclin (tetracyclin – TET); quinolones (ciprofloxacin – CIP, enrofloxacin – ENO and nalidixic acid – NAL); nitrofuran (nitrofurantoin – NIT); sulfonamide (cotrimoxazol – SUT); anfenicol (chloramphenicol – CLO). Strains were considered multiresistant when resistant to three or more antimicrobial categories.27

In search of resistance genes, we employed PCR techniques on the E. coli strains that presented antimicrobial resistant phenotypes. We searched for β-lactam resistance genes (blaTEM,28blaSHV,28blaOXA,28blaCMY,29 and blaCTX-M28); and employed multiplex to access tetracycline (tetA and tetB),30 aminoglycoside (aadA,31aphA,32 and strAB33), sulfonamide (sul1,33sul2,31 and sul334), and quinolone resistance genes (qnrA,35qnrD,36qnrB,35qnrS,37oqxAB,35aac(6)′-Ib-cr,38qnrC,35 and qepA39).

We used the PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) technique on all E. coli isolates in search of characteristic markers for different plasmids of the Inc K/B, W, FIIA, FIA, FIB, Y, I1, F, X, HI1, N, H12 and L/M groups.40

The chi-square test was employed to compare the frequency of bacteria from pet shop, private residences and commercial breeders. p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

ResultsSalmonella spp. was not isolated from the cloacal samples, on the other hand, E. coli was isolated in 10% (9/94) of the analyzed animals: one from a pet shop (1/8–13%), three from private residencies (3/28–11%), and five from commercial breeders (5/58–9%), with no statistical differences between bacterial isolation regarding the individual's origin.

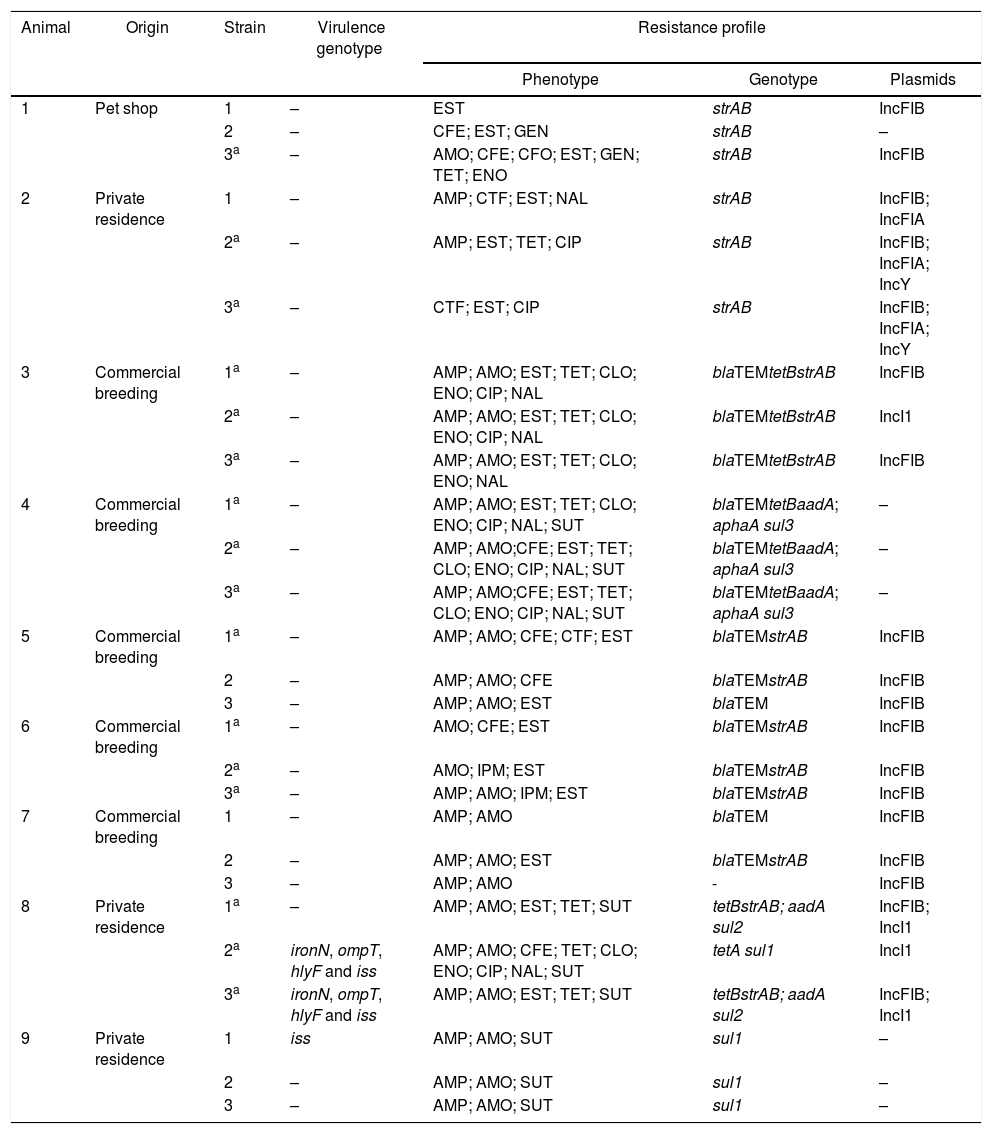

Results of the virulence predictor genes and antimicrobial resistance profiles of all 27 analyzed strains are shown in Table 1.

Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy cockatiels: origin, virulence genotype, antimicrobial phenotype/genotype and plasmids.

| Animal | Origin | Strain | Virulence genotype | Resistance profile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | Genotype | Plasmids | ||||

| 1 | Pet shop | 1 | – | EST | strAB | IncFIB |

| 2 | – | CFE; EST; GEN | strAB | – | ||

| 3a | – | AMO; CFE; CFO; EST; GEN; TET; ENO | strAB | IncFIB | ||

| 2 | Private residence | 1 | – | AMP; CTF; EST; NAL | strAB | IncFIB; IncFIA |

| 2a | – | AMP; EST; TET; CIP | strAB | IncFIB; IncFIA; IncY | ||

| 3a | – | CTF; EST; CIP | strAB | IncFIB; IncFIA; IncY | ||

| 3 | Commercial breeding | 1a | – | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL | blaTEMtetBstrAB | IncFIB |

| 2a | – | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL | blaTEMtetBstrAB | IncI1 | ||

| 3a | – | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; NAL | blaTEMtetBstrAB | IncFIB | ||

| 4 | Commercial breeding | 1a | – | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL; SUT | blaTEMtetBaadA; aphaA sul3 | – |

| 2a | – | AMP; AMO;CFE; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL; SUT | blaTEMtetBaadA; aphaA sul3 | – | ||

| 3a | – | AMP; AMO;CFE; EST; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL; SUT | blaTEMtetBaadA; aphaA sul3 | – | ||

| 5 | Commercial breeding | 1a | – | AMP; AMO; CFE; CTF; EST | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB |

| 2 | – | AMP; AMO; CFE | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB | ||

| 3 | – | AMP; AMO; EST | blaTEM | IncFIB | ||

| 6 | Commercial breeding | 1a | – | AMO; CFE; EST | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB |

| 2a | – | AMO; IPM; EST | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB | ||

| 3a | – | AMP; AMO; IPM; EST | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB | ||

| 7 | Commercial breeding | 1 | – | AMP; AMO | blaTEM | IncFIB |

| 2 | – | AMP; AMO; EST | blaTEMstrAB | IncFIB | ||

| 3 | – | AMP; AMO | - | IncFIB | ||

| 8 | Private residence | 1a | – | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; SUT | tetBstrAB; aadA sul2 | IncFIB; IncI1 |

| 2a | ironN, ompT, hlyF and iss | AMP; AMO; CFE; TET; CLO; ENO; CIP; NAL; SUT | tetA sul1 | IncI1 | ||

| 3a | ironN, ompT, hlyF and iss | AMP; AMO; EST; TET; SUT | tetBstrAB; aadA sul2 | IncFIB; IncI1 | ||

| 9 | Private residence | 1 | iss | AMP; AMO; SUT | sul1 | – |

| 2 | – | AMP; AMO; SUT | sul1 | – | ||

| 3 | – | AMP; AMO; SUT | sul1 | – | ||

AMO, amoxicillin; AMP, ampicillin; CFE, cephalexin; CFO, cefoxitin; CTF, ceftiofur; IPM, imipenem; EST, streptomycin; GEN, gentamicin; TET, tetracyclin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; ENO, enrofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; SUT, cotrimoxazol; CLO, chloramphenicol.

With the exception of APEC-related genes, identified in two birds, we did not detect any other markers related to the remaining ExPEC (papC, papEF, sfa, iucD, fyuA, cnf1, hly, cvaC, malX and iutA) and diarrheagenic E. coli (stx1, stx2, ST, LT, ial, aggR, eae and bfpA).

None of the evaluated strains were positive for O157 and H7 antisera agglutination.

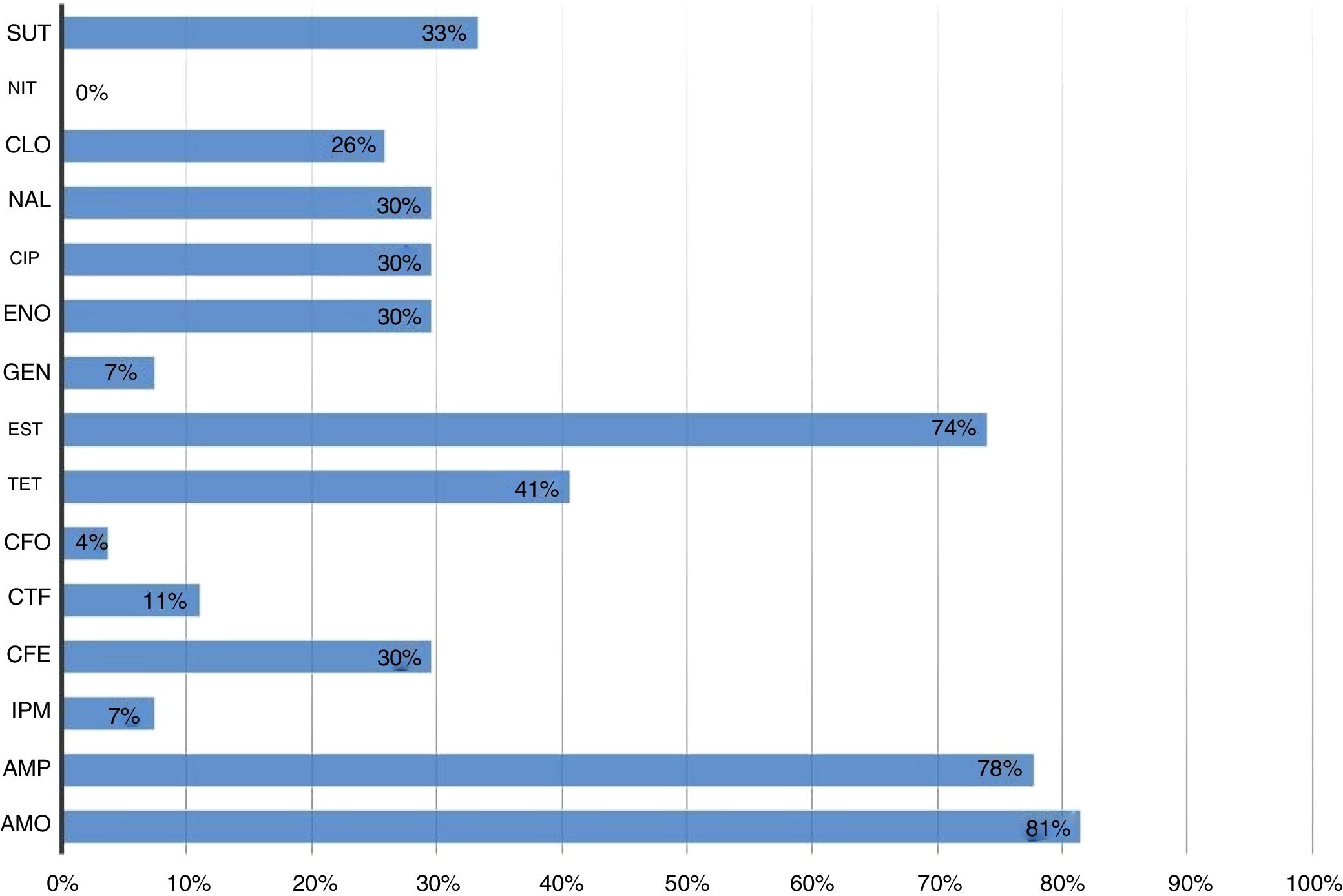

All strains were sensitive to nitrofurantoin. The highest resistance percentage was to β-lactams (93%). Amoxicillin and ampicillin were the antimicrobials with the highest number of resistant strains, 81% (22/27) and 78% (21/27), respectively, followed by streptomycin (74% – 20/27) (Fig. 1).

Resistant Escherichia coli strains isolated from cockatiels according to the tested antimicrobial drugs. SUT, cotrimoxazol; NIT, nitrofurantoin; CLO, chloramphenicol; NAL, nalidixic acid; CIP, ciprofloxacin; ENO, enrofloxacin; GEN, gentamicin; EST, streptomycin; TET, tetracyclin; CFO, cefoxitin; CTF, ceftiofur; CFE, cephalexin; IPM, imipenem; AMP, ampicillin; AMO, amoxicillin.

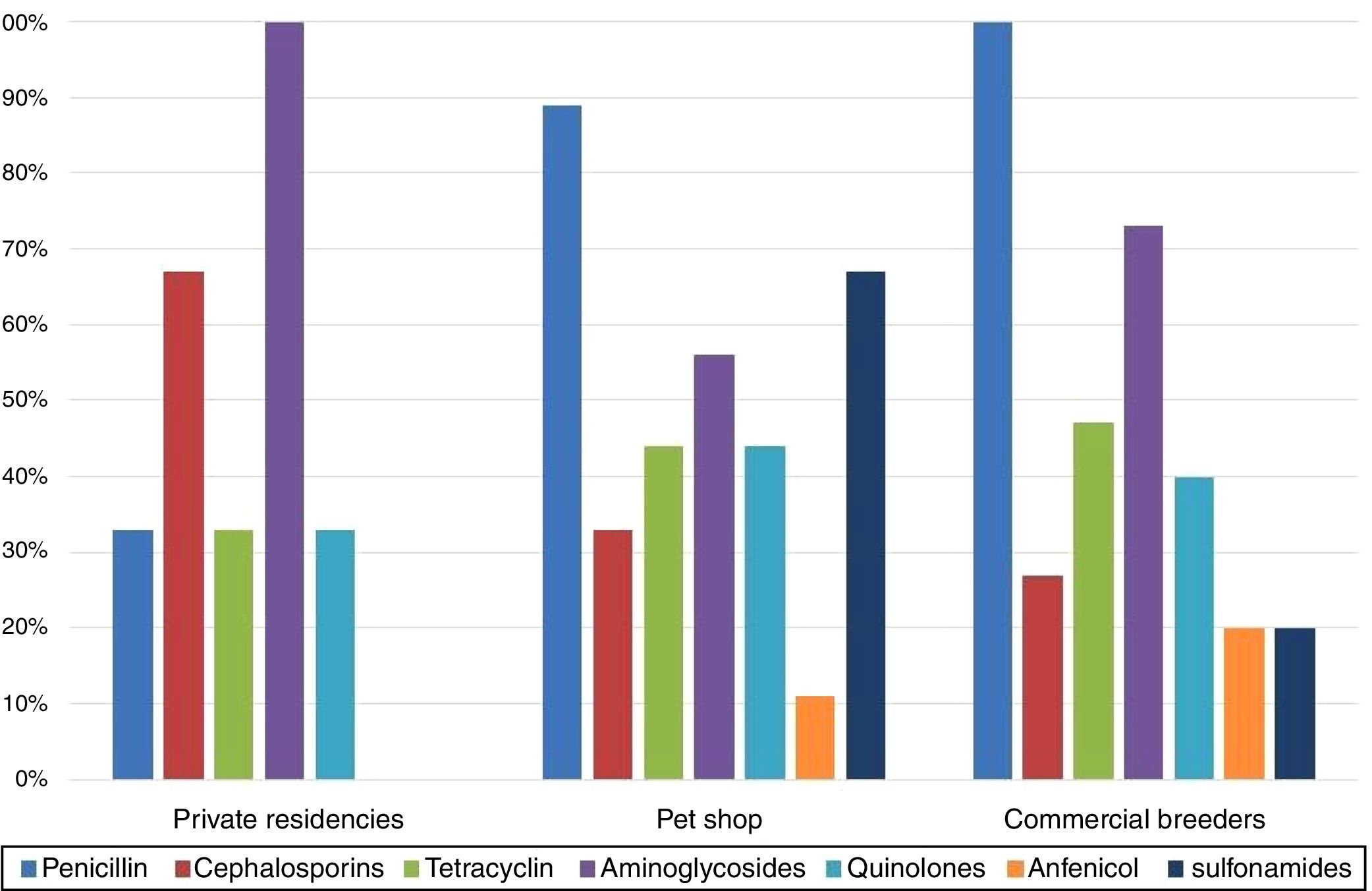

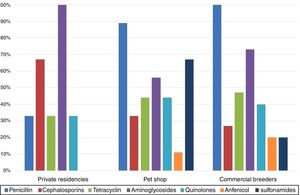

The comparison between isolates’ resistances and cockatiel origin showed that birds from pet shop and commercial breeders were predominantly resistant to penicillins, 89% and 100%, respectively, while private residences isolates were mostly resistant to aminoglycosides (100%) (Fig. 2).

Table 1 shows that 30% (8/27) of the isolates were resistant to seven or more of the tested antibacterial drugs. Resistance to one or more antimicrobial categories was observed in 67% (18/27) of the strains, while 59% (16/27) of them were multiresistant (Table 1). The most frequently observed multiresistance profile was a combination of penicillins, cephalosporins and aminoglycosides (Table 1).

We observed that 96% (26/27) of the E. coli strains presented at least one of the surveyed resistance genes (Table 1). In regards to antimicrobial categories, resistance genes of the aminoglycoside were detected in 77% (20/26) of the strains, 54% (14/26) of the penicillin, 35% (9/26) of the tetracyclin and sulfonamide, and 4% (1/26) of the quinolone isolates. Cephalosporin-related resistance genes were not observed.

The most frequently detected genes in the studied strains were strAB (17/26 – 65%) and blaTEM (14/26 – 54%). The most varied resistance genotype profile was the blaTEMtetB aad aphaA sul3, present in three strains isolated from one single animal that belonged to a commercial breeder (Table 1).

The PBRT technique allowed us to identify and classify plasmids in 74% (20/27) of the E. coli isolates. The IncFIB was the most recurrent Inc, present in 67% (18/27) of the strains, followed by IncI1 (4/27 – 15%), IncFIA (3/27 – 11%) and IncY (2/27 – 7%). Five samples presented more than one plasmid Inc group.

DiscussionData on Salmonella spp. epidemiology in wild and domestic animals are very important in the detection of these agents’ potential reservoirs.41 We did not isolate bacteria from this genus in this study – a suggestion that the studied cockatiels did not present any risks of transmitting such pathogens to humans or animals, as previously observed in a study performed in psittacines.41

Salmonella spp. can be considered one of the most important pathogen in commercial poultry industry, and the presence of these microorganisms is associated with intensive breeding. At the same time, previous studies show a low prevalence of Salmonella spp. in wild birds, and most of the reports are related to the illegal wildlife traded.7,29 In this study, Salmonella spp. was not detected in birds from pet shop, private residences or commercial breeders. However, the zoonotic importance of this agent justifies its monitoring in aviary species.

One of the first survey studies, performed in 125 psittacines of 12 different species, detected E. coli in 14% of the birds42 – results similar to our findings. However, later studies mentioned higher isolation percentages, up to 48%.41

In this research, we did not observe any differences in the isolation of E. coli regards to origin (private residencies, pet shops or commercial breeders), concluding that the people handling these birds were exposed to similar risks, regardless of the birds’ origin.

Herein we tested avian virulence predicting genes in 27 strains: three (11%) isolates from cockatiels living in private residencies presented the iss gene, two of them with iroN, ompT and hlyF genes, all characteristic of the APEC subgroup. Therefore, although these birds were apparently healthy, they carried potentially pathogenic strains.

Studies have shown the existence of genotypic and phenotypic similarities between avian extraintestinal E. coli strains (APEC), urinary infections (UPEC),4,43 and neonatal meningitis.3 Such results reinforce the hypothesis that birds may be reservoirs of E. coli pathogenic to mammals.3,4,43 Thus, it is possible to suggest the potential transmission risk of these zoonotic diseases to the owners and caretakers of the analyzed birds.

Even though other researchers have detected the eae44 and stx245 genes in psittacine fecal samples, suggesting that these birds could be reservoirs of EPEC and STEC to humans, we did not observe virulence genes for the diarrheagenic E. coli in this survey.

All strains evaluated in this study were resistant to at least one of the tested antimicrobials categories, except for nitrofurantoin, similarly to what was observed in a study performed in psittacines from a conservationist breeder.41 Our results showed that 30% of the strains were resistant to seven or more antimicrobial drugs and 59% were multiresistant. E. coli resistance to two or more antimicrobial groups is currently considered a common finding, both in human and veterinary medicine.27,33 This represents a great impact over viable therapeutic options and potential dispersion of these pathogens in the community, one of the most relevant global public health issues.27

The highest resistance percentage was related to β-lactams (93%), of which 89% of the strains were resistant to penicillin. Several authors have also observed a high percentage of penicillin resistance, up to 100%, in psittacines and passeriforms.9 We verified that 52% of the strains presented the blaTEM,28 suggests that up to 90% of E. coli ampicillin resistance is due to TEM-1 and TEM-2 enzymes coded by the blaTEM gene.

The isolates presented increased resistance to aminoglycosides (74%), particularly to streptomycin (67%). Similar resistance levels have been observed in wild birds (63%).46 We detected that 85% of the streptomycin-resistant strains presented the strAB gene, justifying the high resistance levels noticed for this drug.

Similarly, the tetB gene was detected in 80% of the tetracycline-resistant strains. Researchers have obtained high frequencies of tetracycline resistance in E. coli strains of animal origin and tetB gene has also been the most commonly reported gene in human isolates.47

In a study performed in Brazil, E. coli strains isolated from wild frigates presented low ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin resistance indexes.11 However, the strains isolated in our study presented 41% resistance to quinolones. This high resistance percentage may be related to selective pressure, a result of veterinary therapies established with no laboratory support and empirical treatments with no veterinary supervision. This factor is especially relevant when one considers the commercial formulation of this antimicrobial category, which is focused on the avian pet market and commercialized without any governmental control.

In this study, 33% of the sulfonamide-resistant E. coli strains presented the sul1, sul2 and sul3 genes, frequently reported in resistant isolates of human origin.48

Increased Gram-negative resistance is mainly attributed to mobile genes present in plasmids, which may be disseminated within bacterial populations.40,49 Air travels, human migrations and animal transit allow rapid transportation of bacterial plasmids among countries and continents. Four plasmids were detected in this study: IncFIB, IncFIA, IncY and IncI1. The FIB group was observed in strains that presented phenotypical resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides and quinolones. Our findings are in accordance with the available bibliography, which states that plasmids of the IncF family are broadly distributed in E. coli commensals, but carry quinolone and aminoglycoside resistance genes and ESBL encoding genes.40

Strains presenting plasmid IncI1 were phenotypically resistant to penicillins, and one of them to cephalexin. Plasmids IncI1 and IncY are also related to the distribution of ESBL acquisition genes and quinolone resistance.40 Furthermore, IncI1 is characterized by encoding the type IV pili, a virulence factor that contributes to bacterial adhesion and invasion. This virulence characteristic has been related to Shiga toxin producing E. coli (STEC)40 and to the highly pathogenic APEC strains,50 which may contribute to the pathogenic potential presented by the APEC strains with virulence markers detected in this study.

We observed high antimicrobial resistance in the strains isolated from healthy captive cockatiels, including multiresistance, as well, we detected the presence of plasmids and genes related to resistance phenotype. E. coli strains with pathogenic potential presented important APEC virulence factors. From a zoonotic point of view it is important to highlight the relevance of maintaining pets and disseminating these bacteria to other animals, to humans, and the environment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Fabiana T. Konno, Suzana M. Bezerra and Cleide M. da Silva Santana provided technical assistance during the research. CAPES-Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior provided a scholarship to Patricia Silveira de Pontes. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.