The electrocardiogram (ECG) is the oldest and the most frequently used test in cardiology. The aim of this study is to verify, in different patients’ groups, which are the most frequent ECG reports in a cardiology tests clinic.

MethodsThis is a retrospective evaluation of all ECGs performed in a cardiology clinic in Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. The main indications and results were evaluated.

ResultsA total of 1150 ECGs were performed; 63% were normal, and the most frequent abnormalities were altered ventricular repolarization (AVR) and intraventricular conductance disturbance (16% of cases). In the preoperative groups, the ECG report was normal in 67% of cases, and the most frequent abnormality was intraventricular conductance disturbance (32.8%). In the clinical evaluation group, the report was normal in 60%, and the most frequent abnormality was also intraventricular conductance disturbance (18.4%). In the hypertension group, the report was normal in 56%, and the most commonly found abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization (22.5%). In the group with diagnosis or suspect coronary disease, the ECG was normal in 43%, and the most frequent abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization (34%). In the group with tachycardia, the ECG was normal in 65% of cases, and the most frequent abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization (11.7%). In the group of patients with history of syncope, the ECG was normal in all cases.

ConclusionThe ECG was normal in the majority of cases and the most frequent abnormality found was altered ventricular repolarization, independently of the indication for the test performance.

El electrocardiograma (ECG) es la exploración cardiológica más antigua y más comúnmente utilizada. El objetivo de este estudio es verificar, en diferentes grupos de pacientes, cuáles son los informes de ECG más frecuentes en una clínica de exploraciones cardiológicas.

MétodosSe ha llevado a cabo una evaluación retrospectiva de todos los ECG realizados en una clínica de cardiología de Fortaleza, Ceará (Brasil). Se evaluaron las principales indicaciones y los resultados.

ResultadosSe realizó un total de 1150 ECG; un 63% fueron normales, y las anomalías más frecuentes fueron las siguientes: alteración de la repolarización ventricular (ARV) y trastorno de la conducción intraventricular (16% de los casos). En los grupos preoperatorios, el informe del ECG fue normal en el 67% de los casos, y la anomalía más frecuente fue el trastorno de la conducción intraventricular (32,8%). En el grupo de evaluación clínica, el informe fue normal en el 60%, y la anomalía más frecuente fue también el trastorno de la conducción intraventricular (18,4%). En el grupo de hipertensión, el informe fue normal en el 56%, y la anomalía más frecuente observada fue la alteración de la repolarización ventricular (22,5%). En el grupo con diagnóstico o sospecha de enfermedad coronaria, el ECG fue normal en el 43%, y la anomalía más frecuente fue la alteración de la repolarización ventricular (34%). En el grupo con taquicardia, el ECG fue normal en el 65% de los casos, y la anomalía más frecuente fue la alteración de la repolarización ventricular (11,7%). En el grupo de pacientes con antecedentes de síncope, el ECG fue normal en todos los casos.

ConclusiónEl ECG fue normal en la mayoría de los casos y la anomalía observada con mayor frecuencia fue la alteración de la repolarización ventricular, con independencia de cuál fuera la indicación para realizar la exploración.

Among all tests used in cardiology, the electrocardiogram (ECG) is the oldest and the most frequently used. According to American Guidelines on ECG, this test should be done even for patients without cardiopathy suspect, included in the following conditions (class I): (1) for clinical evaluation of individuals older than 40 years; (2) to evaluate patients before the administration of cardiotoxic drugs; (3) to evaluate individuals before ergometric test; (4) to evaluate individuals at any age who have jobs that require high cardiovascular performance (e.g. astronauts, fireman, policeman) or whose performance is linked to public safety (e.g. pilots, bus drivers, air traffic controllers). There is no consensus (class II) regarding the need of ECG in the evaluation of competitive athletes. There is consensus that ECG should not be done (class III) in the routine evaluation of individuals younger than 40 years without risk factors.1–4

As preoperative evaluation, the ECG should be performed (class I) in patients older than 40 years and in heart transplant donors or cardiopulmonary transplant receptors. There is no consensus (class II) regarding the ECG performance in preoperative evaluation in patients aged 30–40 years. There is consensus that ECG should not be done (class III) in patients younger than 30 years in the preoperative period, without risk factor for coronary disease.1

The aim of this study is to verify, in different patients’ groups, which are the most frequent ECG reports in a cardiology tests clinic.

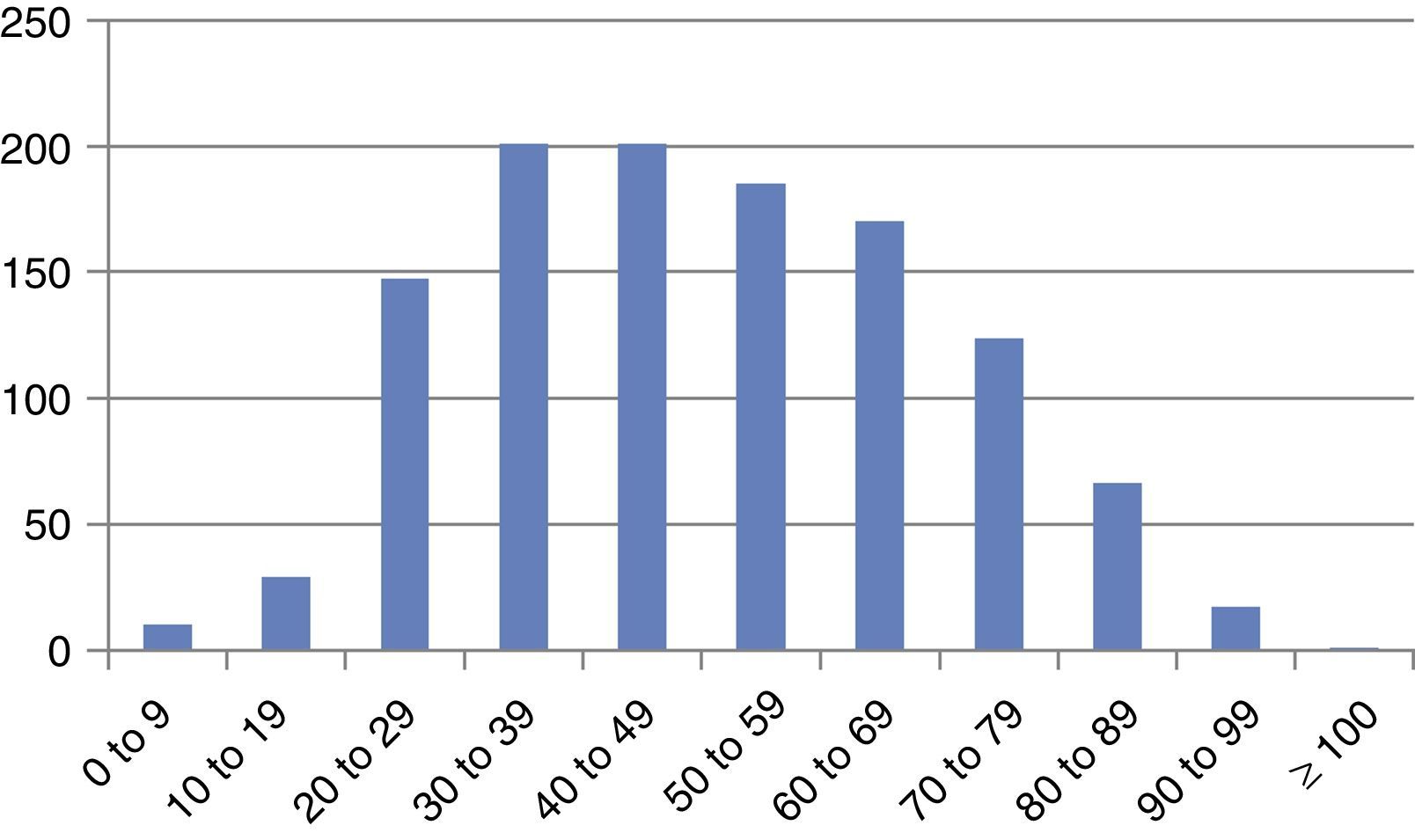

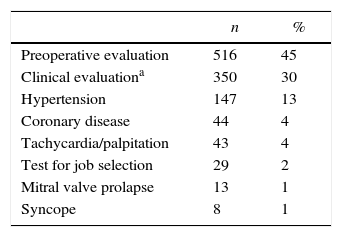

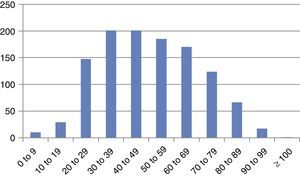

Materials and methodsIn the period between 1st August and 31st October 2012 a total of 1150 ECGs were performed in the Unicordis, a cardiology tests clinic in Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. The study was retrospective and all patients in the period were included in the study. The population was of ambulatory patients. The performance and interpretation of ECGs was done according to recent guidelines, published by the Brazilian Society of cardiology.5 Patients’ age distribution is summarized in Fig. 1. The most prevalent age was 30–49 years. The majority of patients (61%) were female. The indications for ECG performance were preoperative evaluation (45%), clinical evaluation (30%), hypertension (13%), coronary insufficiency (4%), tachycardia/palpitation (4%), examination for job selection process (2%), mitral valve prolapse (1%) and syncope/pre-syncope (1%) (Table 1). All the ECGs were performed by a Cardiologist.

ECG indications.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative evaluation | 516 | 45 |

| Clinical evaluationa | 350 | 30 |

| Hypertension | 147 | 13 |

| Coronary disease | 44 | 4 |

| Tachycardia/palpitation | 43 | 4 |

| Test for job selection | 29 | 2 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 13 | 1 |

| Syncope | 8 | 1 |

A total of 1150 tests were analyzed; 444 were male (38.7%) and 706 were female (61.3%), with a mean age of 49.6±19.2 years. Age distribution according to ECG indication was: preoperative evaluation – 48.4±17.7, clinical evaluation – 51.1±20.2, hypertension – 57.3±19.0, coronary insufficiency – 52.6±20.5, tachycardia/palpitation – 40.2±21.1, examination for job selection process – 42.0±10.4, mitral valve prolapse – 31.8±11.7 and syncope/pre-syncope – 44.2±26.1 years.

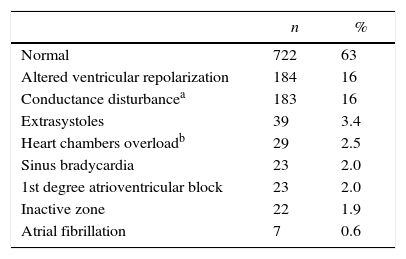

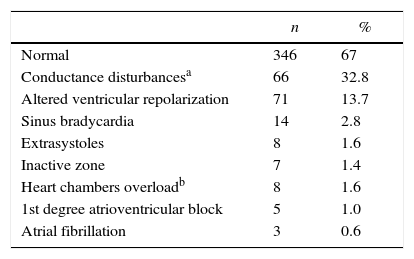

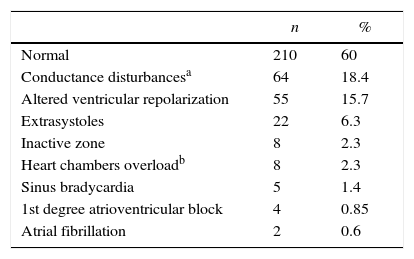

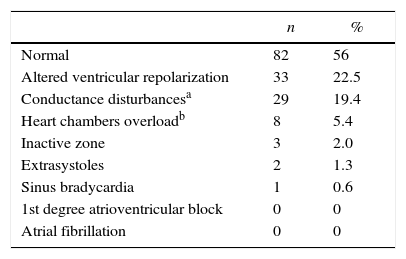

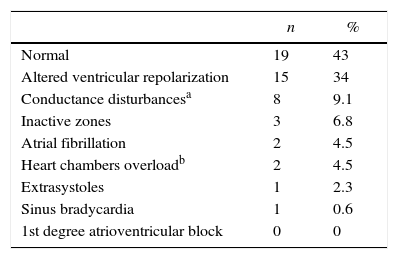

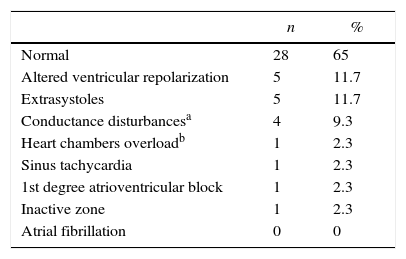

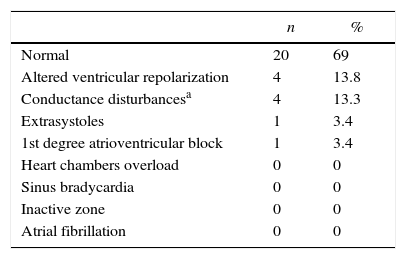

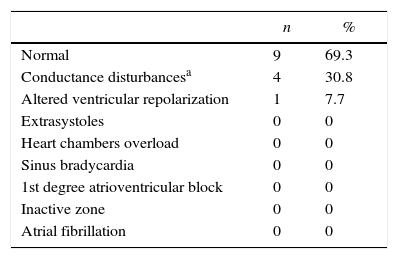

Considering the total of 1150 tests, 63% were normal, and the most frequent abnormalities were: altered ventricular repolarization (AVR) and intraventricular conductance disturbance, each one in 16% of cases (Table 2). In the preoperative groups, the ECG report was normal in 67% of cases, and the most frequent abnormality was intraventricular conductance disturbance, in 32.8% (Table 3). In the clinical evaluation group, the report was normal in 60%, and the most frequent abnormality was also intraventricular conductance disturbance, in 18.4% (Table 4). In the hypertension group, the report was normal in 56%, and the most commonly found abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization, in 22.5% (Table 5). In the group with diagnosis or suspect coronary disease, the ECG was normal in 43%, and the most frequent abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization, in 34% (Table 6). In the group with tachycardia, the ECG was normal in 65% of cases, and the most frequent abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization, in 11.7% (Table 7). In the group of individuals who performed ECG as a test for job selection, it was normal in 69% of cases, and the most frequent abnormality was altered ventricular repolarization, in 13.8% (Table 8). In the group of patients with mitral valve prolapse, the report was normal in 69.3%, and the most frequent abnormality was intraventricular conductance disturbance, in 30.8% (Table 9). In the group of patients with history of syncope, the ECG was normal in all cases.

ECG reports.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 722 | 63 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 184 | 16 |

| Conductance disturbancea | 183 | 16 |

| Extrasystoles | 39 | 3.4 |

| Heart chambers overloadb | 29 | 2.5 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 23 | 2.0 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 23 | 2.0 |

| Inactive zone | 22 | 1.9 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 | 0.6 |

ECG reports in the group of preoperative evaluation.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 346 | 67 |

| Conductance disturbancesa | 66 | 32.8 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 71 | 13.7 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 14 | 2.8 |

| Extrasystoles | 8 | 1.6 |

| Inactive zone | 7 | 1.4 |

| Heart chambers overloadb | 8 | 1.6 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 5 | 1.0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 | 0.6 |

ECG reports in the group “clinical evaluation”.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 210 | 60 |

| Conductance disturbancesa | 64 | 18.4 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 55 | 15.7 |

| Extrasystoles | 22 | 6.3 |

| Inactive zone | 8 | 2.3 |

| Heart chambers overloadb | 8 | 2.3 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 5 | 1.4 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 4 | 0.85 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 | 0.6 |

ECG reports in the group with hypertension.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 82 | 56 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 33 | 22.5 |

| Conductance disturbancesa | 29 | 19.4 |

| Heart chambers overloadb | 8 | 5.4 |

| Inactive zone | 3 | 2.0 |

| Extrasystoles | 2 | 1.3 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 1 | 0.6 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0 |

ECG reports in the group with coronary disease.

ECG reports in the group performing tests for job selection.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 20 | 69 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 4 | 13.8 |

| Conductance disturbancesa | 4 | 13.3 |

| Extrasystoles | 1 | 3.4 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 1 | 3.4 |

| Heart chambers overload | 0 | 0 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 0 | 0 |

| Inactive zone | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0 |

ECG reports in the group with mitral valve prolapse.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 9 | 69.3 |

| Conductance disturbancesa | 4 | 30.8 |

| Altered ventricular repolarization | 1 | 7.7 |

| Extrasystoles | 0 | 0 |

| Heart chambers overload | 0 | 0 |

| Sinus bradycardia | 0 | 0 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 0 | 0 |

| Inactive zone | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0 |

The present study evaluated the main indication and results of ECGs performed in a reference center of a metropolitan area. The main indications were for preoperative evaluation and “clinical evaluation” (when ECG is done when a person will begin a new job, as part of health evaluation). The majority of ECGs were normal, and the most frequently found abnormalities were intraventricular conductance abnormality and altered ventricular repolarization. In a previous study evaluating the risks for an adult patient in non-cardiac elective surgery the ECG was performed due to the presence of cardiovascular comorbidities in 80% of cases, respiratory comorbidities in 42%, advanced age in 53% and as a routine in 10%.6 In our cohort, there was no specific cause for ECG performance in the preoperative period.

The altered ventricular repolarization (AVR) was the most frequent abnormality observed in our study in the general sample, in the groups of hypertension, coronary disease, tachycardia and in those who were undergoing the test for job selection.

“Strain” pattern in the ECG was evaluated in 8554 hypertensive patients in the LIFE study, and were “blind” treated with atenolol or losartan. Strain pattern, defined as the presence of ST segment depression with asymmetric and inverted T-wave in the derivations V5 and V6, was present in 971 patients (11%).7 In our group of patients with hypertension, AVR was observed with a higher incidence (22%), but we have to point that in these 22% are included ECGs with AVR with strain pattern and unspecific ventricular repolarization abnormalities.

Major and minor ECG abnormalities in asymptomatic women were compared with cardiovascular events and mortality in a post-hoc analysis in the study “Women's Health Initiative”. Minor abnormalities were considered as: 1st and 2nd degree atrioventricular block, prolonged QT-interval, ST-segment minor abnormalities, left atrium overload, and frequent atrial or ventricular extrasystoles. Major ECG abnormalities were: atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, 2nd degree atrioventricular block, left bundle branch block, right branch block, inactive electrical zone, and left ventricle hypertrophy with strain pattern. The adjusted risk for coronary events in patients who presented minor ECG abnormalities was 1.55, and for patients with major abnormalities it was 3.01.8

The “Reykjavic Study” evaluated the epidemiologic, clinical and prognostic characteristics of angina in the non-recognized acute myocardial infarction and detected that 1/3 of infarctions were not recognized.9 The finding of electrical inactive zone in our patients was not frequent. In the general sample, it occurred in 1.9% of cases. The sub-group with higher frequency of electrical inactive zone, as expected, was that of patients with suspected or diagnosed coronary disease, with a 6.8% frequency.

The Chicago Electric Company Study also evaluated the association between unspecific ST-segment abnormalities and cardiovascular mortality. A total of 1673 men were selected from the electric company workers, aged between 44 and 55 years, without evidence of coronary disease and without significant ECG abnormalities at the beginning of the study. Among the 1673 men, 173 developed ST-segment unspecific abnormalities during a 5-years follow-up. The authors linked the number of annual ECGs with ST-segment abnormalities, and found a relative risk for death of 2.28, 2.39, 2.30 and 1.6, respectively, for 4, 3, 2 or 1 ECG with this abnormality.10

The prevalence, prognosis and implications of unspecific ST-segment abnormalities were also studied in the elderly. A total of 233 out of 3224 participants of the “Cardiovascular Health Study” presented ST-segment unspecific abnormalities at the beginning of the study. After 39,518 patients-years of follow-up, the presence of unspecific ST-segment abnormalities was associated with mortality due to coronary disease (relative risk of 1.76), but there was no association with infarction incidence. This fact suggests that ST-segment unspecific abnormalities are particularly associated with risk for death due to primary arrhythmia.11

In our cohort, the presence of atrial or ventricular extrasystoles was observed in 3.4% of cases of the general sample, and its higher frequency occurred in the groups of individuals who performed the test due to tachycardia (11.7%). It is known that the presence of extrasystoles has prognostic value for heart disease, and it has been shown that frequent ventricular extrasystoles after physical exercise works as a death predictor.12

A simple ECG can help to detect silent atrial fibrillation (AF) before the first cerebrovascular event, especially in patients with multiple cardiovascular conditions. AF occurred in 7 out of 132 patients in a case series (5.3%). Among these patients, there were four survivors from stroke, two with diabetes and one with hypertension. The prevalence of AF was higher in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and AF. AF was found in 3% of patients with hypertension without other risk factors, in 7% of patients with two risk factors and in 11% of patients with hypertension, diabetes and stroke.13 In our cohort, AF was present in 0.6% of cases in the general sample. The group with higher frequency was that of individuals with suspect or diagnosis of coronary disease (4.5%). In our group with hypertension, there was no case of AF.

In summary, the ECG was normal in the majority of cases and the most frequent abnormality found was altered ventricular repolarization, independently of the indication for the test performance.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.