Scimitar Syndrome; low frequency complex congenital anomaly, is characterized by a partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage; in which the right pulmonary veins, flow directly into the hepatic portion of the VCI. It can be associated with cardiac and pulmonary pathology. We describe four patients with diagnosis of Scimitar Syndrome in our hospital; as well as its evolution and applied therapeutic approach.

El síndrome de la cimitarra es una anomalía congénita compleja de escasa frecuencia que se caracteriza por un drenaje venoso pulmonar anómalo parcial en el cual las venas pulmonares derechas desembocan directamente en la porción suprahepática de la VCI. Se puede encontrar asociado a dolencias cardíacas y pulmonares. Describimos 4 pacientes con el diagnóstico de síndrome de la cimitarra en nuestro hospital, así como su evolución y la actitud terapéutica aplicada.

Scimitar Syndrome is a complex and infrequent congenital anomaly characterized by an anomalous partial venous pulmonary drainage in which the right pulmonary veins connect directly to the suprahepatic portion of the CVI or to the atrio-cava union. This syndrome is generally associated to right pulmonary hypoplasia, systemic arterial supply to the right lung which can generate a dead short from left to right; and in some occasions, a cardiac dextroposition due to a dextrorotation, as well as bronchopulmonary sequestration with agenesis of the upper right or middle right bronchus.1–3 In the Scimitar Syndrome, the anomalous drainage of the pulmonary veins comes from the right lung that is often, as previously mentioned, hypoplastic; therefore, the degree of shunt left-right that is objectified will be inversely proportional to the degree of the present hypoplasia; a higher degree of pulmonary hypoplasia leads to lower left-right shunt.4

So far today, four diagnosis of the Scimitar Syndrome have been performed in our hospital. The first, diagnosis and intervention of a 9-year-old patient; anomalous partial venous pulmonary drainage from right pulmonary arteries to the inferior supradiadragmatic cava vein, associated to pulmonary sequestration; a connection mouth of the PPVV collector to LA with a pericardial patch is performed, a part of the septum secundum is removed, and performed again in eight months’ time due to the dehiscence of the IAC patch closure, connecting the CVI with the LA; control tests with a favorable evolution in our unit.

The second diagnosis is the case of a 3-year-old patient with a neonatal diagnosis after performing an echocardiography for heart murmur; objectifying two right pulmonary veins draining in CVI; the study is completed with a pulmonary CT scan which showed right pulmonary hypoplasia, with aberrant artery from the abdominal aorta which supplies the right lower lobe posterobasal segment. Remaining the patient asymptomatic and with no clinical nor echocardiography repercussion on the right cavities, it is decided to adopt an expecting attitude because of the poor surgical anatomy.

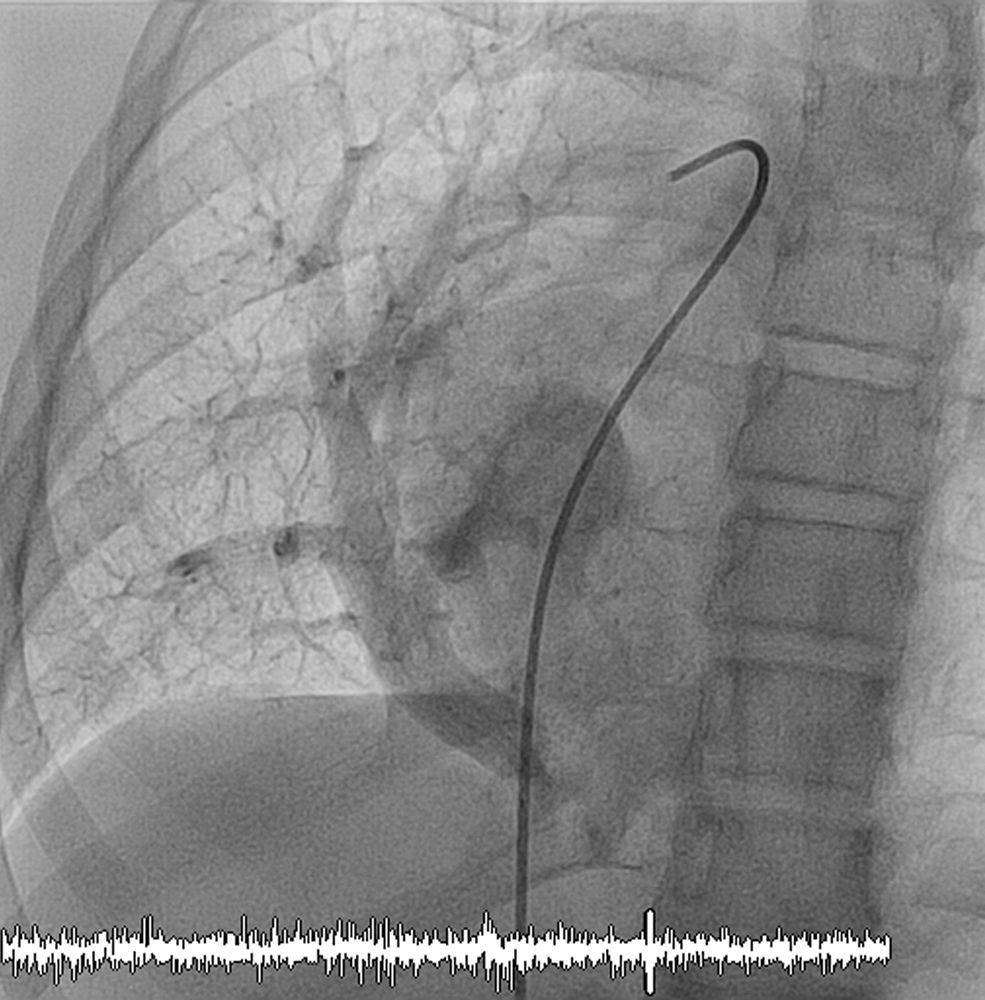

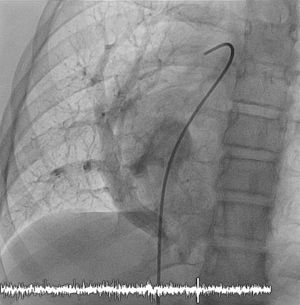

The third case is an 11-year-old patient, sent to our consulting room because of a dextrocardia; after performing the echocardiography it is suspected that she has an anomalous partial venous pulmonary drainage, which is eventually confirmed after the angio CT scan: both right pulmonary veins drain into hepatic inferior cava; being also noticed an aortic collateral emerging from the celiac trunk which supplies to part of the right inferior lobe (Fig. 1). A cardiac catheterization is therefore performed confirming the existence of an aberrant aortic branch which drained into a small pulmonary region with no repercussion over right cavities, reason why it is decided to not proceed on it (Fig. 2).

The last case is an early diagnosis, when an echocardiography is performed on a 1-month-old patient due to symptomatic congestive heart failure. It is observed a dilatation of the right cavities with severe PH and anomalous pulmonary drainage of a collector that gathers the two right pulmonary veins to CVI suprahepatic, with stenotic ostium and obstructive flow. Findings are confirmed with an angio CT scan. Despite the poor surgical anatomy, we proceed to the surgical correction with reimplantation and expansion of the anomalous connector.

The name Scimitar is awarded to the syndrome because of the similarity of the opacity that the anomalous collector vein projects in the thoracic X-ray. It represents 0.5–2% of the total number of congenital heart diseases.4

The clinic depends on the degree of left-right shunt, on the existence of defects in the associated atrial septal and on the magnitude of the PH.2 The clinical profile is divided in a group of children with aged less than one year, considering the infantile variant that has a worse prognosis, in which it is common a higher incidence and severity of cardiac anomalies (75%), pulmonary hypertension and heart failure.3 In this group, the symptoms of heart failure may be caused by an obstruction in the drainage (a rare cause) or by associated anomalies, such as pulmonary sequestration, occurring in some cases with heart failure and leading to an active therapeutic attitude.4

On the other hand, the benign form of manifestation and asymptomatic presentation, called “of the big child” or “of the adult”. It usually occurs in children over 3 years old, with a favorable prognosis, normally by incidental diagnosis, commonly after performing a control chest X-ray.3

The diagnosis can be based on the typical Scimitar image which is objectified in the thoracic X-ray, complemented with an angio TC scan, a ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy and a cardiac MRI.2 The echocardiography allows us to assess the PV mouth, the degree of PH, a shunt from left to right and associated heart disease.3

Regarding the treatment, it depends on the presence of symptoms, PH and heart failure. The surgical treatment is mainly based on the direct or indirect connection of the anomalous drainage to the LA. Grown up children and adults are generally asymptomatic and do not normally need treatment; in case they needed it, the strategy should be, firstly, the occlusion of collateral or surgical correction of the anomalous drainage and secondly, the correction of the associated cardiac anomalies.3 Finally, it must be taken into consideration that in those cases associated to pulmonary sequestration, in which a surgical resection or percutaneous embolization is performed, the hypoplastic lung may increase in size, therefore increasing the shunt that causes the anomalous drainage and indicating the need of surgical correction.4

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.