Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is increasingly understood to be a disease that presents not only with septal hypertrophy but also with diverse anomalies of the mitral valve and subvalvular apparatus. In this review, we describe the involvement of the mitral valve in the generation of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and discuss the surgical approaches to managing this complex condition.

La cardiomiopatía hipertrófica está cada vez más entendida como una enfermedad que se presenta no solo con evidencia de hipertrofia septal, sino también con diversas anormalidades de la válvula mitral y su aparato subvalvular. En este artículo describimos la contribución de la válvula mitral a la generación de la obstrucción del tracto de salida del ventrículo izquierdo en pacientes con cardiomiopatía hipertrófica obstructiva, además de discutir los diferentes abordajes quirúrgicos disponibles para tratar esta compleja patología.

One of the first modern descriptions of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) was provided by the pathologist Robert Donald Teare, who reported asymmetric cardiac hypertrophy in a case series of autopsies of young adult patients.1 Just two years later, Teare and his colleagues described in more detail the “asymmetrical hypertrophy of the heart, a condition in which the interventricular septum in particular is grossly hypertrophied and bulges into both ventricular cavities.”2 Around this time, several groups were devoting considerable attention to what we now know as HCM. Early explorations of the disease and descriptions of surgical attempts to alleviate left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction observed in some patients with HCM have been well documented.3,4

Given this history, it is not surprising that our understanding of HCM and the surgical approach to treating profoundly symptomatic patients was focused singularly on the hypertrophic septum. Increasingly, however, HCM is understood to be a disease of not just a hypertrophic septum, but of a contributing mitral valve (MV) apparatus. The availability of more modern imaging has demonstrated the MV also plays a very significant role in obstructive forms of HCM.5,6

The most recent ACC/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HCM acknowledge that approximately three quarters of these patients have a left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, with the mitral valve contributing to the principal mechanisms through which the obstruction is generated.7 In cases where patients have significant LVOT obstruction and persistent, debilitating symptoms despite maximal medical therapy, septal reduction therapy (SRT) is an appropriate treatment. Surgical SRT via septal myectomy is felt to be the appropriate treatment for the widest range of patients.7

The purpose of this paper is to describe the involvement of the MV, subvalvular apparatus and presence of SAM in the generation of LVOT obstruction in patients with HCM, and to make the argument that any surgical management of these patients must, at the very least, evaluate potential MV abnormalities and consider whether they should be addressed. We will describe the presence of MV abnormalities in patients with HCM and discuss the surgical management of HCM patients with symptomatic LVOT obstruction, with a focus on learning from the experience of several major HCM programs around the world. This review of the literature will be contextualized with a description of the clinical journey of an HCM patient treated by one of the authors (JBG).

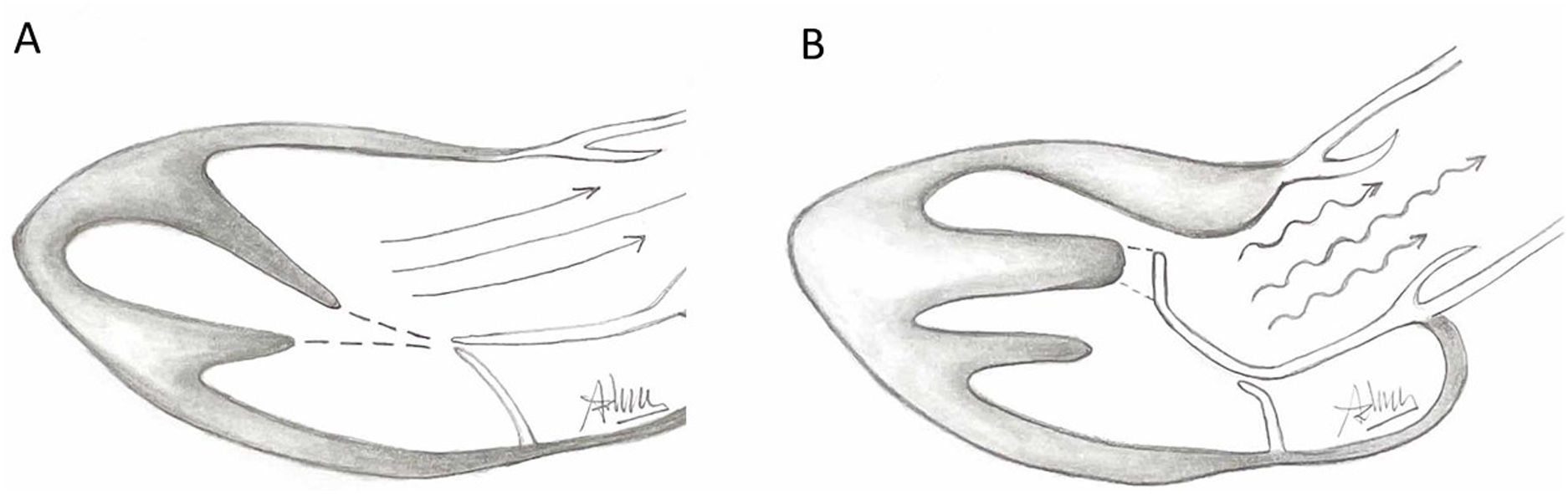

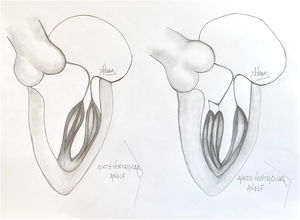

Presence of MV abnormalities in HCMMitral valve abnormalities and SAM are not present in all patients with HCM but are acknowledged elements of the heterogenous HCM phenotype. The ACC/AHA guidelines describe a number of “morphologic abnormalities” that are observed in patients with HCM, including “hypertrophied and apically displaced papillary muscles, … anomalous insertion of the papillary muscle directly in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (in the absence of chordae tendinae), [and] elongated mitral valve leaflets.”7 Descriptions in the literature are myriad, and not a recent discovery, with some reports dating back to the late 1960s.5,8,9 Anteriorly displaced papillary muscles may contact the septum directly during systole, or can create slackness in the mitral valve leaflets, while mid-leaflet and other anomalous insertion of the chordae tendinae can contribute to MV leaflet tenting. All of these conditions, alone or in combination allow the leaflets to be dragged into the left ventricular flow stream.5 Elongated mitral valve leaflets may also result in inadequate coaptation, contributing to both SAM and MR (Figs. 1 and 2).

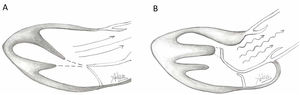

Illustration of normal mitral leaflet coaptation and orientation of papillary muscles axis towards center of mitral valve allowing normal flow through LVOT (A) in contrast to turbulent flow through LVOT caused by abnormal orientation of hypertrophic anterolateral papillary muscle, the presence of a mildly hypertophic sigmoid septum, and secondary ectopic chordae tethering and bending the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve causing a hockey stick deformity.

A normal papillary muscle anatomy and coaptation between anterior and posterior leaflet of mitral valve with wide aorto ventricular angle (left) contrasts markedly with an abnormal anteriolateral papillary muscle group with it axis oriented towards the aortic valve instead of mitral valve (right).

Our understanding of the prevalence of MV abnormalities in HCM is growing. Approximately a decade ago, Kown and colleagues described an independent association between abnormal papillary muscles and LVOT obstruction,10 while work by Maron and colleagues described elongated MV leaflets in patients with HCM compared to non-HCM controls.11 In the surgical literature, inconsistent reporting hinders attempts to understand the proportion of patients undergoing septal reduction surgery that also have SAM or other MV abnormalities. One Canadian study reported 50% of HCM patients referred for surgery had significant SAM,12 while a Chinese surgical group observed SAM in all of their surgical patients.13 A series presented by the Cleveland Clinic seemed to indicate a smaller proportion of patients requiring MV intervention, with fewer than 15% of the patients in their series receiving MV procedures at the time of their septal reduction surgery.14

The diversity of MV and subvalvular apparatus anatomy observed in patients with HCM is impressive, as shown in descriptions from high-volume surgical centers performing SRT.5,15 This phenotypic heterogeneity in MV anatomy in patients with HCM must also be considered in the context of the patient's septal thickness and the ventricular level at which their obstruction is generated (i.e. basal, mid-ventricular or apical). Taken together, these elements help to explain why careful pre-operative planning and a comprehensive diagnostic imaging assessment using modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and cine computed tomography (CT) are essential. Specifically, the ACC/AHA guidelines note that CMR can “reliably characterize specific features of the LVOT anatomy that may be contributing to SAM-septal contact and obstructive physiology and, therefore, are relevant to strategic planning for septal reduction procedures.”7

Case presentationThe patient was a 32-year-old male presenting with exertional dyspnea and two near syncopal episodes while exercising. He had a family history of HCM; his mother had been diagnosed with what was then called idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis, now known as HCM, and underwent two septal myectomies in the early 1980s.

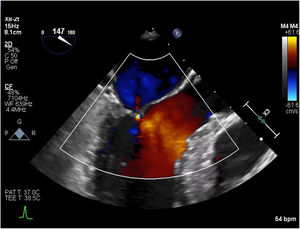

An initial resting TTE showed evidence of SAM but a resting gradient of only 8mmHg that increased to 22mmHg during Valsalva maneuver (Fig. 3). Given the patient's family history of HCM and his worsening symptoms, he was referred to a cardiologist for more targeted and dynamic investigations. A cardiac MRI demonstrated hypertrophic anterolateral papillary muscle with abnormal insertion, potential evidence of SAM, but no clear gradient through the LVOT. A cine CT demonstrated a septum of 13mm with clear evidence of SAM (Fig. 4). Dynamic testing was done using treadmill exercise echocardiography, which identified a maximal LVOT gradient during peak exercise was of 313mmHg with evidence of mitral regurgitation (MR). The results of these tests led to the diagnosis of obstructive HCM with severe LVOT gradients during dynamic testing.

During his diagnostic workup, which took place over the course of several months, the patients was increasingly symptomatic and reported NYHA class III symptoms despite maximal doses of disopyramide and bisoprolol. After several discussions between the patient and his cardiologist, he was referred for surgery due to failure of medical therapy.

Surgical management of HCMIn 1959, a group of British clinicians, including Dr. Teare and the surgeon Dr. W.P. Cleland, published a case report of a surgical treatment of obstructive cardiomyopathy.2 Nevertheless, the name that is most frequently associated with the surgical management of HCM is Dr. Andrew Morrow, for whom the Morrow procedure is named and who was diagnosed with HCM himself.16 The Morrow procedure was the standard surgical approach to treating HCM for many years, and involved a relatively limited resection of muscle from the basal septum.16

Today, surgeons perform an extended septal myectomy, resecting significantly more tissue to better alleviate LVOT obstruction, and many concomitantly address the anomalous chordae tendinae, misaligned papillary muscles and other MV abnormalities. Articles by Affronti et al.17 and Gharibeh et al.18 provide significant detail and context about the various approaches and techniques used to address the diversity of MV abnormalities seen in patients with HCM for the interested reader. As well, Kotkar and colleagues provides excellent illustrations of the diverse phenotypes they have observed in their HCM surgical program.15

It must be noted that although MV abnormalities are well described as a component of the HCM phenotype,7 there is some controversy about the necessity of concomitant procedures of the MV and subvalvular apparatus during septal reduction surgery. The Mayo clinic has described their extensive experience with the surgical management of HCM, including descriptions of diverse MV anomalies,15 but their approach is generally to use septal myectomy alone to treat LVOT obstruction19 and suggest that this approach is sufficient for almost all patients.20 The surgical program at Toronto General Hospital, one of the primary referral centers in Canada, has published the results of their experience using isolated septal myectomy to treat HCM with good results.12

This approach contrasts with other centers that more routinely address MV anomalies during SRT. A recent series by clinicians from Milan report that approximately half of HCM patients undergoing SRT required mitral valve intervention. They reported that addressing the MV apparatus may be more important when patients do not have a particularly thick septum.21 The Cleveland Clinic similarly reports MV interventions in approximately a third of their SRT procedures for HCM, and also noted the importance of addressing the MV in patients with thin septae.22 A report from Oregon is perhaps even more pronounced in its support of addressing MV anomalies; Song and colleagues describe routine papillary muscle realignment in a cohort of patients undergoing SRT, with very good results.23

At present there is no definitive consensus about whether addressing the MV apparatus is essential for alleviating LVOT obstruction. The guidelines clearly reflect this controversy, advising “transaortic extended septal myectomy” for patients with obstructive HCM who experience debilitating symptoms, but note that “some centers achieve these results with isolated extended septal myectomy, [while] other centers have found value in including revision of the anterior mitral leaflet or apparatus.”7

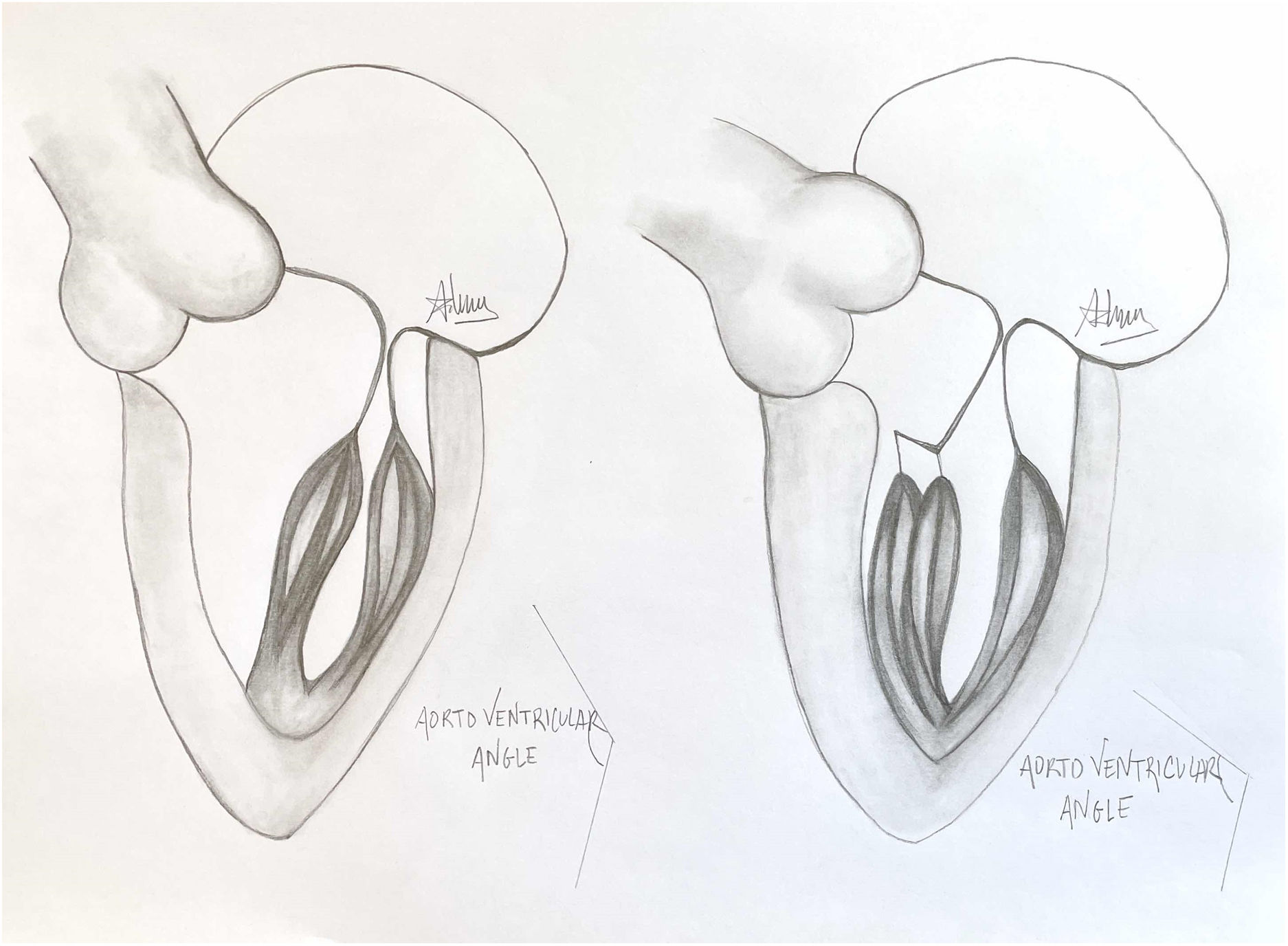

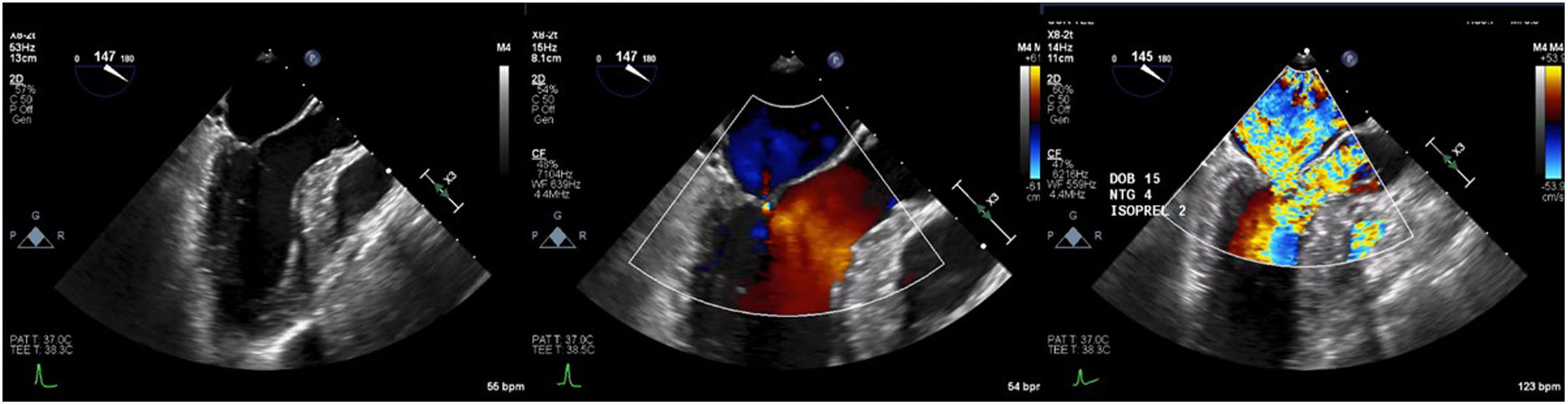

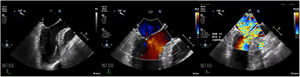

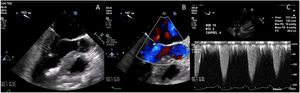

Case presentationThe patient underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) after the induction of anesthesia to evaluate the LVOT gradient and mechanism of obstruction. Under resting conditions, the TEE demonstrated a 13mm septum, hypertrophic anterior lateral papillary muscle group, SAM without associated mitral insufficiency, and a peak gradient of 30mmHg. A gradient was provoked with isoproterenol drip and nitroglycerine; in these conditions, the patient's LVOT gradient increased to 283mmHg with torrential MR (Fig. 5).

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram showing the presence of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (A), Doppler waveform with SAM but no mitral regurgitation (B), and a severe LVOT gradient with mitral regurgitation after the administration of isoproterenol, dobutamine and nitroglycerine (C).

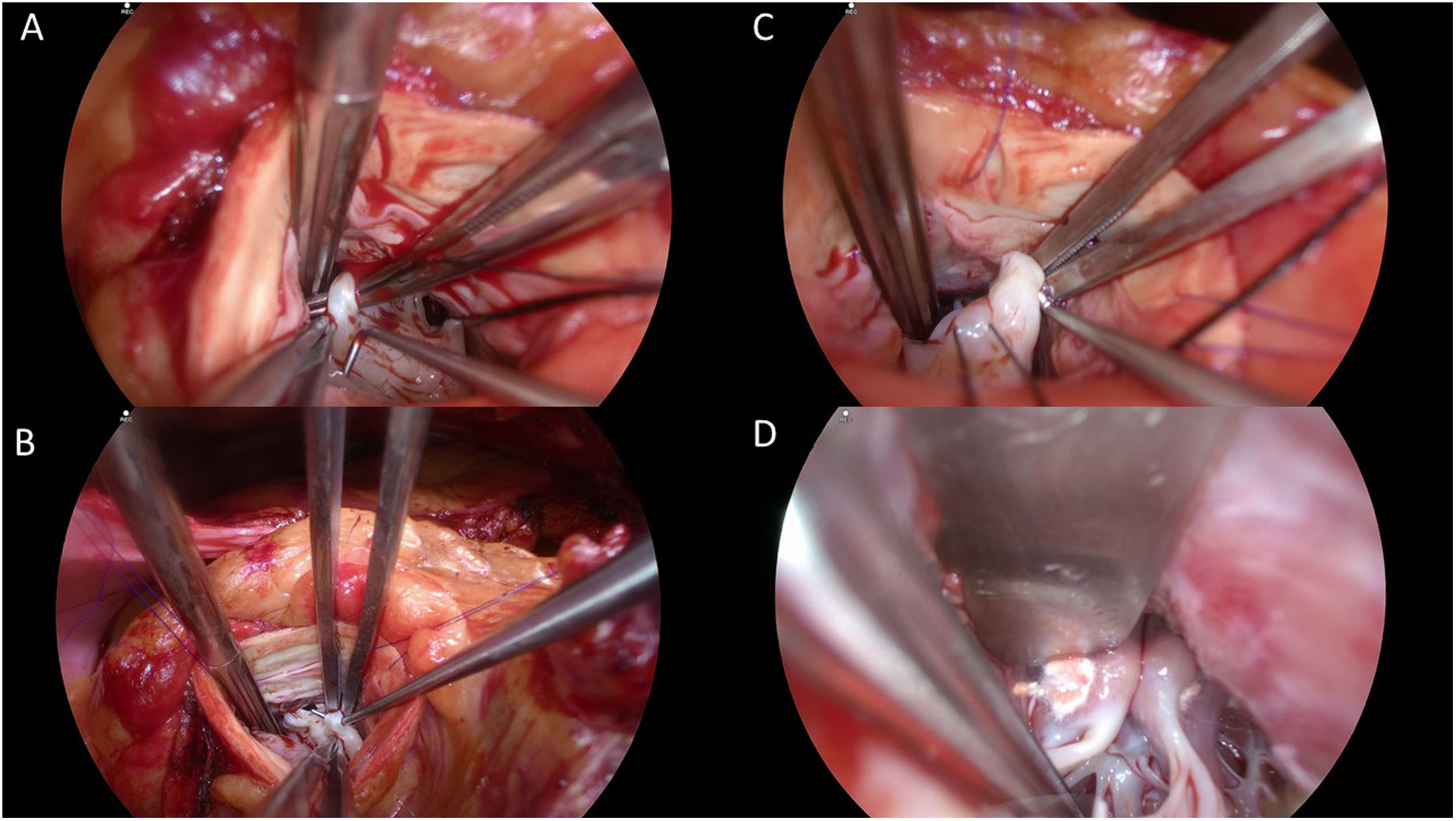

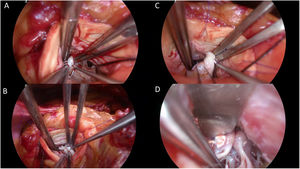

The patient underwent an extended septal myectomy, with the resection of a segment approximately 30mm by 35mm by 7mm at the level of the septum (Fig. 6). Seven abnormal secondary chordae were resected (Fig. 7A–C) followed by a realignment of the anterior lateral papillary muscle group towards the posterior medial papillary muscle group using a 4–0 Gore-Tex pledgeted suture (Fig. 7D). Abnormal muscular connections between the septum and the base of the anterolateral papillary muscle group were resected allowing full mobility of the anterolateral papillary muscle group that was abnormally inserted.

Intraoperative images illustrating thickened ectopic chordae inserting into the base of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve close to anterior trigon (A), ectopic secondary chordae inserting towards the posterior trigone anterior leaflet of the mitral valve B, evidence of tethering effect of secondary chordae encircled by Prolene thread seen side-to-side with normal A2 segment of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve being lifted by a nerve hook (C), and papillary muscle realignment using a 4–0 Gore-Tex suture tied over pledgets.

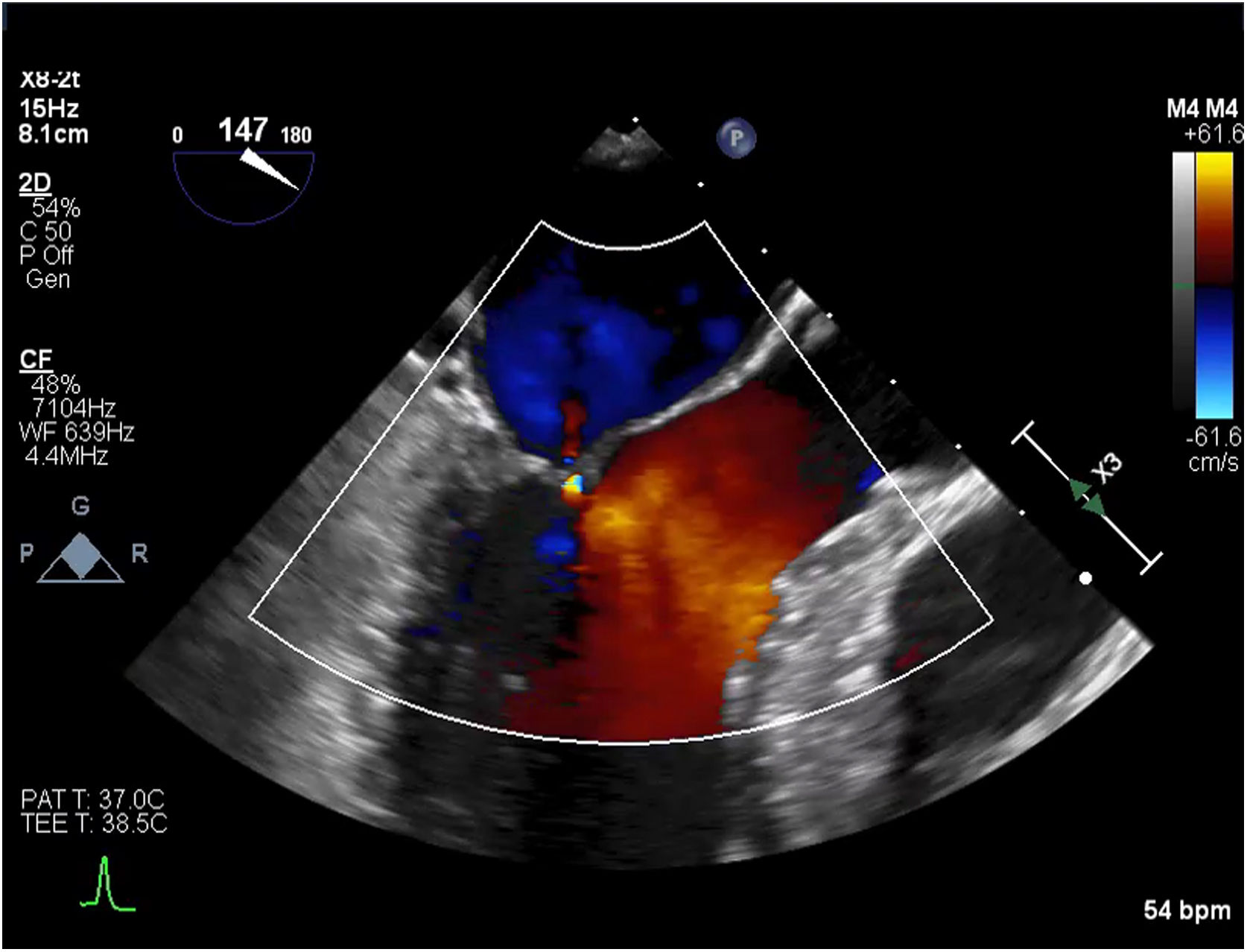

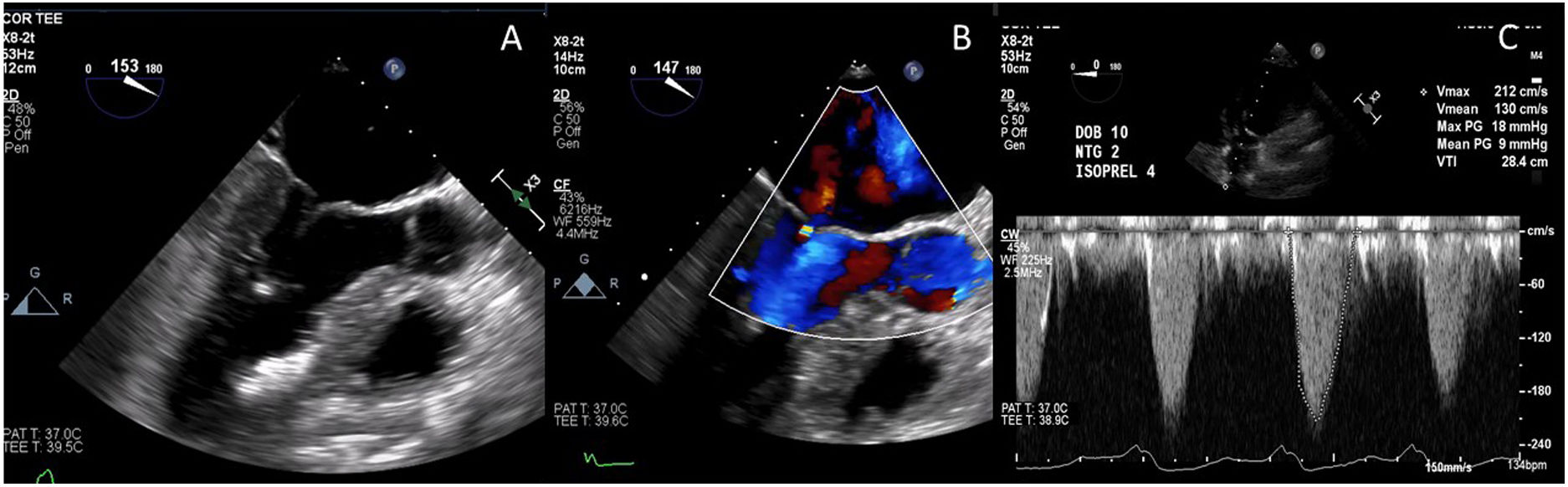

The post-procedural TEE demonstrated normal coaptation between the anterior and posterior leaflets of the mitral valve, with a coaptation point significantly displaced towards the posterior annulus (Fig. 8). There was no evidence of SAM, and trace mitral insufficiency. Under maximal provocation the peak gradient through the LVOT was 18mmHg with a mean of 9mmHg. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course in hospital, and was discharged home on post-operative day 4.

Post-procedural transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrating coaptation of the anterior and posterior leaflets of the mitral valve displaced towards the posterior annulus (A); trace mitral regurgitation during provocation with isoproterenol, dobutamine and nitroglycerine (B); and peak and mean gradients under maximal provocation (C).

Our understanding of HCM has evolved over the past several decades, and the contributions of the MV and subvalvular apparatus to the generation of LVOT obstruction is now well understood. Myriad and diverse MV anomalies are accepted as part of the HCM phenotype, and these must be considered when diagnosing and managing this complex disease.

While there is some controversy about the necessity of addressing the MV during SRT, many surgeons see it as an essential tool to eliminate SAM and alleviate obstruction. The results of some experienced surgeons in high volume centers suggest that good alleviation of LVOT obstruction can be achieved through an isolated septal myectomy. However, the literature increasingly reflects a wider adoption of a variety of techniques to address the MV and apparatus with very good short- and mid-term results. Many reports in the literature consistently suggest that addressing MV anomalies has led to the reliable elimination of SAM and reduction of LVOT obstructions under both resting and dynamic conditions.

There is another potential consequence of a pointed focus on septal thickness and isolated myectomy to treat obstructive HCM, and that is the potential exclusion of patients without significant septal hypertrophy from consideration for SRT. Our case presentation was carefully chosen, highlighting the profound dynamic obstruction and disabling symptoms that can be observed in an HCM patient with a relatively thin septum. This young patient had been monitored for HCM due to his family history, but the absence of a grossly hypertrophic septum resulted in his symptoms of exertional dyspnea being mis-diagnosed as exercise-induced asthma for many years. After careful investigation by a cardiologist with expertise in cardiac MR and an interest in HCM, his profound dynamic obstruction was diagnosed. Interestingly, this patient was discouraged from pursuing SRT at a large center that limits its practice to isolated septal myectomy, as they did not feel confident that surgical intervention would improve this patient's symptoms or quality of life. This patient experienced profound improvement in his symptoms following an extended septal myectomy with resection of anomalous chordae and realignment of his anterior lateral papillary muscles. He has resumed regular activities, including travel, a busy work life and exercise. It is important for clinicians to carefully consider the diverse mechanisms through which LVOT obstruction can be generated in patients with HCM, and surgeons should be strongly encouraged to tailor their operation to the individual phenotype of each patient they bring to the OR.

One other potential consideration when evaluating whether or not to integrate concomitant MV and apparatus procedures as part of the standard SRT is to consider if they might lend themselves to simplified or safer procedure with an easier learning curve. The scarcity of septal myectomy surgeons has been acknowledged for many years.24 The current supply in most countries is insufficient, and many skilled myectomy surgeons are well into the latter years of their career. Training the next generation of surgeons to perform SRT on patients with HCM is essential, but the challenges and risks of the procedure make that training difficult. In some ways, surgical treatment of HCM today is similar to mitral valve repair twenty years ago, with a variety of centers extolling the virtues of a diversity of techniques to treat a condition that is relatively common and afflicting a comparatively young patient population. Modern MV repair is a safe and widely-available procedure, and while there is still some variability in technique, the preference has shifted away from leaflet resection and towards the use of Gore-Tex neochordae. We would suggest that one reason for this is the ability to adjust or reverse the repair if needed; once tissue is resected, there is no way back. Some techniques that address MV anomalies, including realignment of papillary muscles using a pledgeted Gore-Tex suture, also offer reversibility in case an adjustment is required. One experienced myectomy surgeon reported that incorporating papillary muscle realignment into his SRT procedures reduced the need for more complicated MV techniques.23 It is worth exploring whether some of these techniques might prove beneficial to surgeons during their learning curve, to better ensure the elimination of SAM and LVOT obstruction in cases where a dramatic resection of septal tissue is either not possible or poses an unacceptable risk of creating an iatrogenic ventral septal defect (VSD). Given the urgent need to train more surgeons in these techniques, no avenue should go unexplored. If realigning papillary muscles or resecting anomalous chordae help a larger number of surgeons to safely and adequately address LVOT obstruction in patients with HCM, certainly these techniques should be considered for wider adoption.

When I (JBG) was first operating on patients with HCM, I identified a need to protocolize the operation in order to ensure success. I did not have the benefit of a fellowship in SRT, I had the benefit of strong support from the HCM cardiologist at my institution, who provided comprehensive support and extremely thorough diagnostic imaging. The majority of my patients presented without severely hypertrophic septae, and most had clear MV anomalies that were contributing to LVOT obstruction. I devised a protocol for myself to approach each operation. I began by resecting septal tissue to address that component of LVOT obstruction, and to increase visibility into the ventricle. Then I assess and resect any anomalous chordae. Lastly, I perform a realignment of the anterolateral papillary muscles. This approach is tailored to each patient, but I have found it to deliver consistent results for my patients, and would suggest that approaching this very complex surgery in a clear, linear manner helped to reduce my learning curve and allowed me to provide even my earliest patients with excellent results. Let me note, however, that SRT is not an operation to be undertaken lightly. I suspect that one of the reasons that there is a paucity of surgeons performing SRT is the potential for a single mistake to create catastrophic problems in a patient population that is often relatively young; nobody wants to be responsible for a massive VSD or complete heart block in a 35 year old patient.

Finally, we would respectfully advocate that those surgeons with the benefit of experience and a long history of successful cases should take steps to report their results more uniformly. The reporting of MV anomalies, SAM and MR is inconsistent and oftentimes missing from surgical case series in the literature, which makes it difficult or impossible to compare patient populations and outcomes between centers with different surgical approaches. If we are to move SRT from select high-volume centers to become a more widely-available technique, we must share data, compare outcomes, and work collaboratively to identify which techniques can be broadly adopted and easily taught to the next generation of myectomy surgeons. Too many patients find themselves desperately in need of SRT, but with few or no experienced surgeons in their city or even their country to perform this life-changing operation. HCM centers of all types should make a concerted effort to more clearly, consistently and transparently report their experiences, to the benefit of all.

Patients with HCM present with a diverse array of MV anomalies, many of which contribute to LVOT obstruction. While support for concomitant MV procedures during surgical myectomy is not universal, there is strong support in the literature for excellent, durable results when these procedures are undertaken.

Ethical disclosuresThe description of the case example in the article has been written in a way to not identify the patient, and the patient provided written permission for his case example to be used.

FundingThe authors acknowledge the generous support of the Cannstatter Foundation, Inc.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

The authors wish to acknowledge the generous support of the Canstatter Foundation, Inc. We also wish to express our thanks to Paloma Segura Amoros for her illustrations, and to the patient described in this article, who provided permission for details of his case to be used.