Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is a primary liver neoplasm whose only curative treatment is surgery. The objective of this study was to determine the prognostic factors for survival of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treated surgically with curative intent.

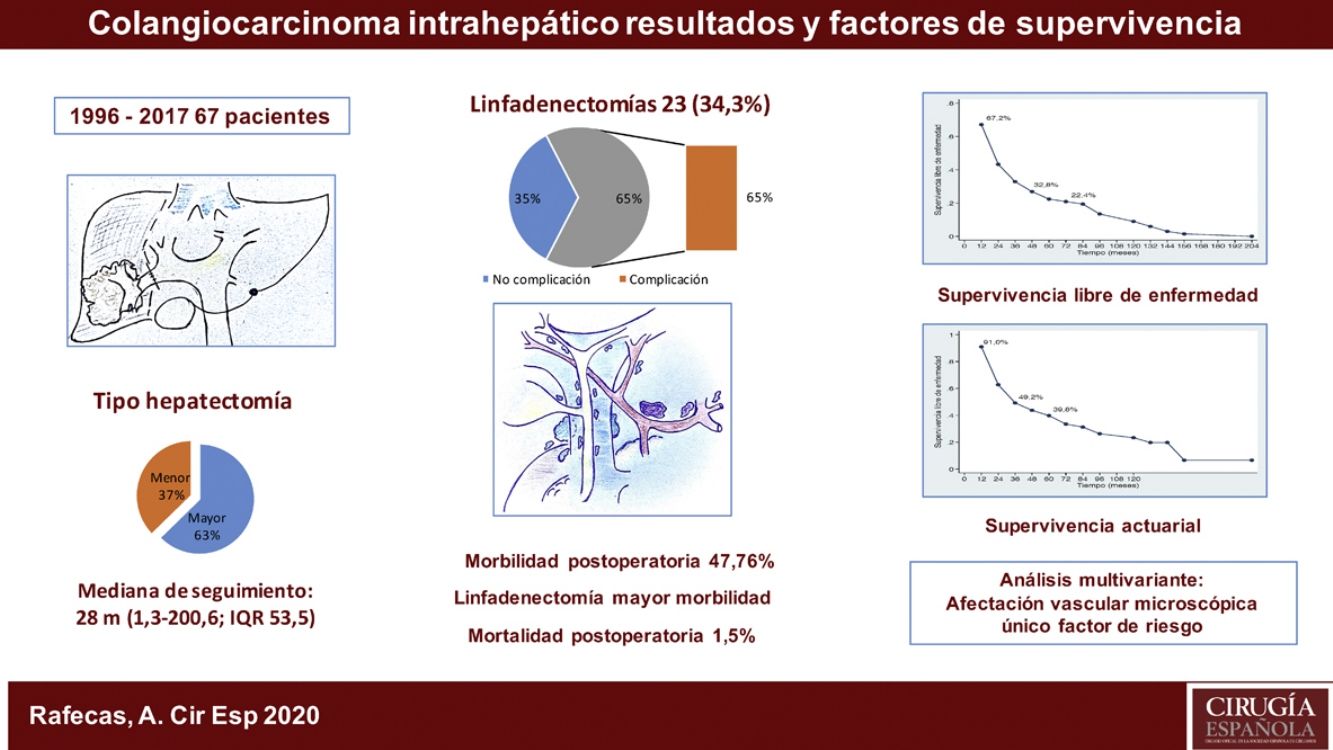

MethodsSixty-seven patients who had been treated surgically for this neoplasm were collected at Bellvitge University Hospital between 1996 and 2017. Epidemiological, clinical, surgical, anatomopathological, morbidity, mortality and survival data have been analysed.

ResultsPostoperative study reflects our centre’s experience in the surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma over a period of 21 years. Lymphadenectomy was associated with increased morbidity, and vascular invasion in the pathological study was the most important risk factor in the survival analysis.

ConclusionsThis study reflects our centre's experience in the surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma over a period of 21 years. Lymphadenectomy was associated with increased morbidity, and vascular invasion in the pathological study was the most important risk factor in the survival analysis.

El colangiocarcinoma intrahepático es una neoplasia primaria hepática de mal pronóstico, cuyo único tratamiento curativo es la cirugía. El objetivo de este trabajo ha sido determinar los factores pronósticos de supervivencia del colangiocarcinoma intrahepático tratado quirúrgicamente con intención curativa.

MétodosSe ha recogido una serie de 67 pacientes intervenidos quirúrgicamente de esta neoplasia en el Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge entre 1996 y 2017. Se han analizado los datos epidemiológicos, clínicos, quirúrgicos, anatomopatológicos, de morbilidad, de mortalidad y de supervivencia.

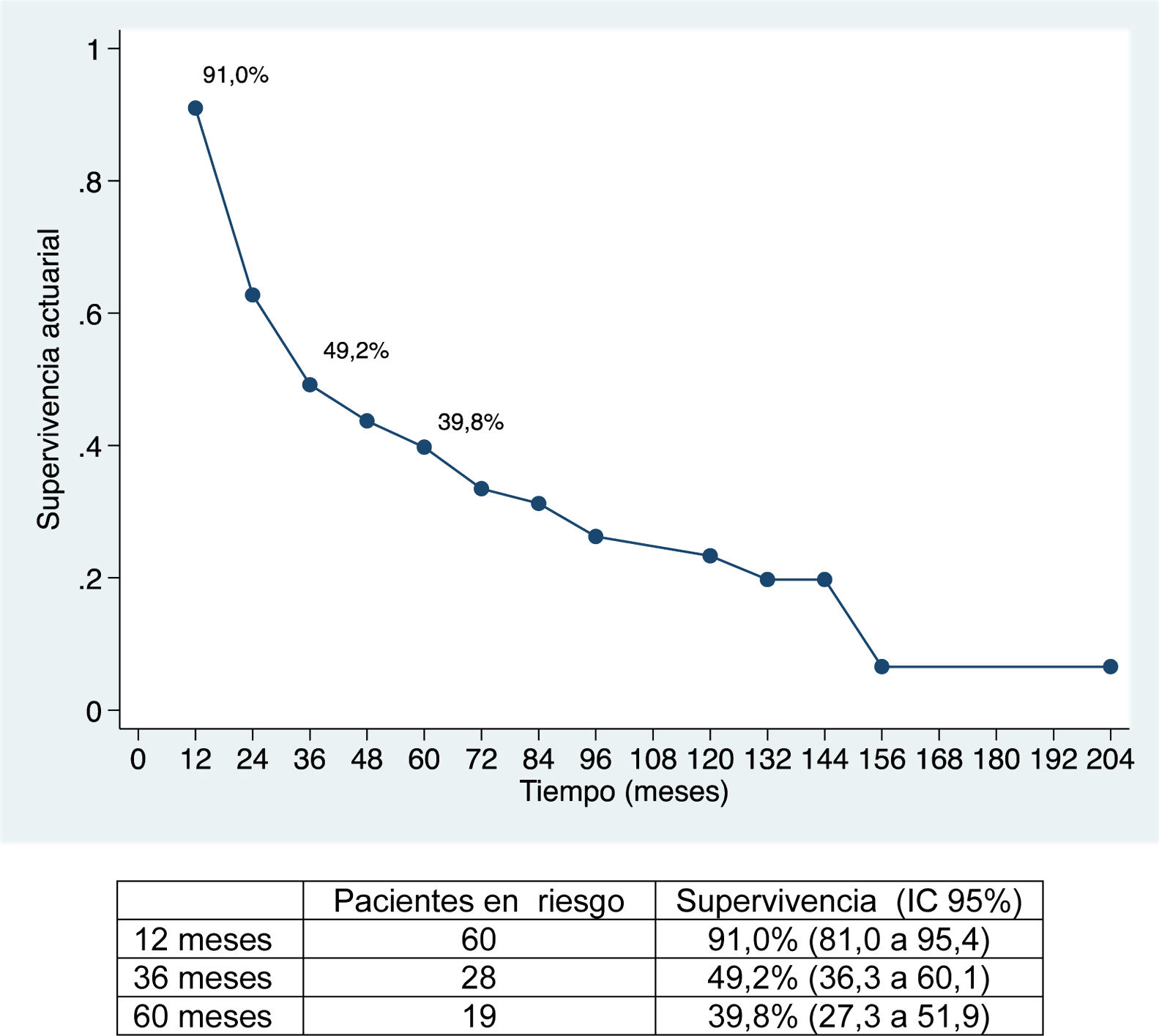

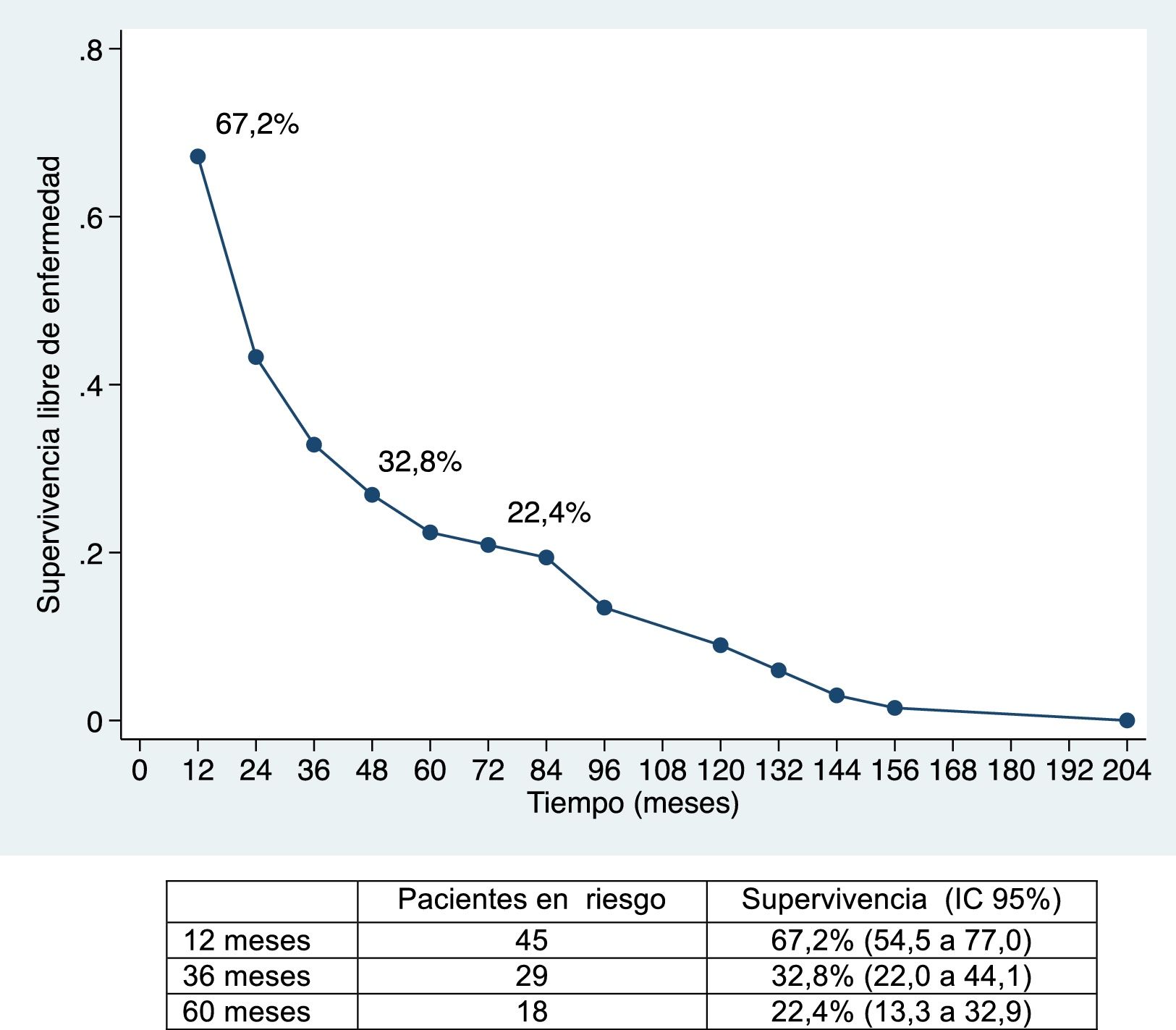

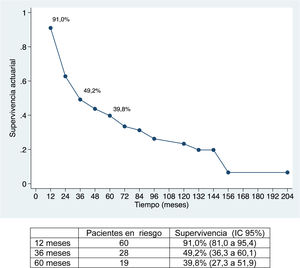

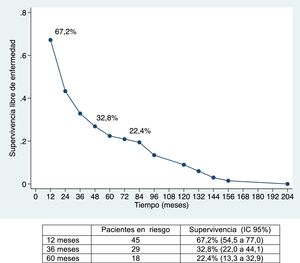

ResultadosLa morbilidad postoperatoria ha sido del 47,76% y la mortalidad postoperatoria de 1,5%. La linfadenectomía se ha asociado a mayor morbilidad. La supervivencia global ha sido de 91%; 49,2% y 39,8% a los 12, 36 y 60 meses, respectivamente, y la supervivencia libre de enfermedad de 67,2%; 32,8% y 22,4%. La morbilidad postoperatoria en forma de reintervención quirúrgica, la invasión vascular y la quimioterapia adyuvante han demostrado ser factores de mal pronóstico. La invasión vascular en el estudio anatomopatológico fue el factor de riesgo de mayor importancia en la supervivencia.

ConclusionesEste estudio recoge la experiencia de nuestro centro en el tratamiento quirúrgico del colangiocarcinoma intrahepático durante un periodo de 21 años. La linfadenectomía se ha asociado a mayor morbilidad y la afectación vascular en el estudio anatomopatológico ha sido el factor de riesgo más importante en cuanto a la supervivencia.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is a neoplasm that develops from the epithelial cells of the intrahepatic bile ducts. It represents less than 3% of gastrointestinal tumors and 15% of cases of primary liver cancer. It is the second most frequent neoplasm, behind hepatocarcinoma1. Chronic HBV and HCV infection, liver cirrhosis of any cause, and other disorders, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, have been indicated as risk factors for the development of this neoplasm1,2.

Symptoms are nonspecific and, in most cases, it is diagnosed as an incidental finding during the follow-up of chronic liver disease. The diagnosis is based on imaging studies. On ultrasound, it appears as a hypoechoic focal lesion. On computed tomography (CT) scans, it is observed as an irregular hypodense lesion, with involved margins and a variable degree of delayed uptake in the portal phase. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a hypointense image on T1 and hyperintense on T23,4.

Biopsy of the lesion is indicated in cases in which the diagnosis is uncertain or in unresectable patients for palliative chemotherapy treatment. Regarding tumor markers, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is only elevated in one-third of patients, while carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA19.9) is more sensitive but not very specific since it is also elevated in other types of gastrointestinal neoplasms3,4.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has a poor prognosis, and only surgical treatment with curative intent is capable of offering acceptable survival4,5. However, several studies have shown that radiofrequency ablation of tumors smaller than 3 cm can be useful in cirrhotic patients or in cases of recurrence6,7. Patients treated with surgical resection have a mean 5-year survival of 25%–40%, with a median survival of 20–22 months. In contrast, unresected patients have a median survival of 6–9 months1,5,8. Factors related with poor prognosis include: multifocality, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion and positive surgical margins1,3,5.

This study is based on the analysis of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treated surgically at our hospital with curative intent. We analyze surgical and pathological factors to assess the influence of lymphadenectomy on postoperative complications, as well as prognostic factors for recurrence and survival.

MethodsData were collected from patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma who had been treated surgically with curative intent between January 1996 and October 2017.

For the analysis, we only used clinical variables that were available for more than 30% of the patients, so variables such as diabetes mellitus, body mass index or hypertension could not be assessed. Liver resection was indicated in patients diagnosed with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by imaging techniques (CT or MRI) or by biopsy if the diagnosis was uncertain. Patients who were considered unresectable were those with parenchymal metastatic disease or celiac or retroperitoneal lymph node disease, those requiring liver resection with insufficient remnant despite preoperative portal embolization, and patients with advanced or decompensated chronic liver disease with Child–Pugh score B or C. As for surgical treatment, major liver resection was defined as resection of 3 or more segments, and minor resection was limited to 2 segments. Lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilum was performed in the case of suspected lymph node involvement (based on the imaging study) and in the case of extended liver resections to improve staging. Morbidity was analyzed based on the Clavien-Dindo9 classification, hospital stay, and perioperative mortality (within 30 days or during initial hospitalization). All patients had a minimum follow-up of 12 months, with tumor markers and imaging studies (CT or MRI) every 6 months. The resection margins were analyzed in millimeters. After reviewing all the pathological reports, the 8th edition of the TNM10 system was used to classify them. If there was no contraindication, adjuvant chemotherapy was indicated at the discretion of the responsible oncologist in stages II and III.

Statistical analysisIn the descriptive analysis of the data, the qualitative variables were expressed in absolute numbers and percentages, and the quantitative variables as median and interquartile range. For the description of global and disease-free survival, the actuarial method was used, using 12-month periods and expressing the median and patients at risk after 1, 3 and 5 years. For the comparison of survival rates between tumor stages, the Kaplan–Meier method was used with the log-rank technique. The analysis of risk factors associated with mortality and recurrence was done using Cox regression models; for the multivariate analysis, we chose variables with clinical relevance or those that showed significance P < .2 in the univariate analysis. A P value <.05 was considered significant. For the statistical analysis, the Stata 12.0 program (StataCorp, CollegeStation, Texas, USA, 2011) was used.

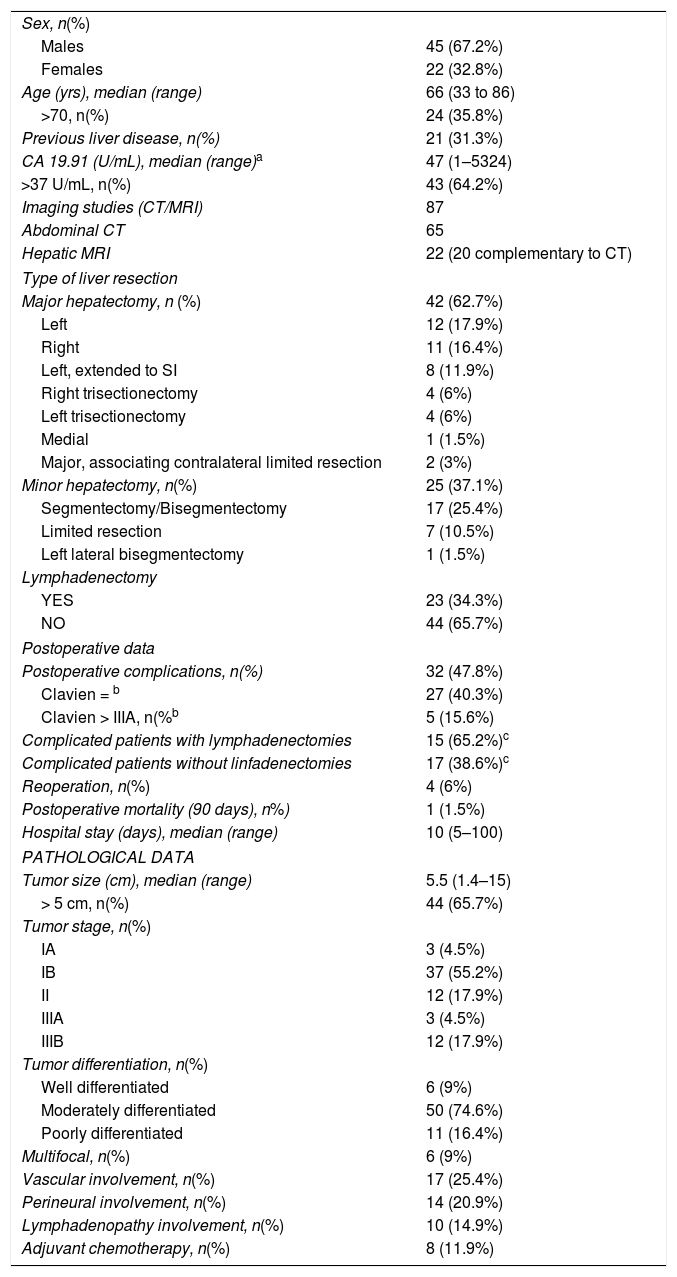

ResultsWe operated on 67 patients, including 45 men (67.2%) and 22 women (32.8%), with a median age of 66 years (range: 33–86 years). Twenty-one of these patients (31.3%) had previous liver disease: enolic in 15 cases, 2 associated with HBV, 4 with HCV, one case with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and another with sclerosing cholangitis. The pathology study identified liver cirrhosis in 9 cases, portal fibrosis in 8, chronic hepatitis in 2, steatohepatitis in one and no parenchymal alterations in one case. At the time of diagnosis, 10 patients had lymphadenopathies in the hepatic hilum. Regarding tumor markers, CA19.9 values were available for 60 patients (89.6%), which were above normal in 36 (60.0%) (Table 1).

Clinical data.

| Sex, n(%) | |

| Males | 45 (67.2%) |

| Females | 22 (32.8%) |

| Age (yrs), median (range) | 66 (33 to 86) |

| >70, n(%) | 24 (35.8%) |

| Previous liver disease, n(%) | 21 (31.3%) |

| CA 19.91 (U/mL), median (range)a | 47 (1–5324) |

| >37 U/mL, n(%) | 43 (64.2%) |

| Imaging studies (CT/MRI) | 87 |

| Abdominal CT | 65 |

| Hepatic MRI | 22 (20 complementary to CT) |

| Type of liver resection | |

| Major hepatectomy, n (%) | 42 (62.7%) |

| Left | 12 (17.9%) |

| Right | 11 (16.4%) |

| Left, extended to SI | 8 (11.9%) |

| Right trisectionectomy | 4 (6%) |

| Left trisectionectomy | 4 (6%) |

| Medial | 1 (1.5%) |

| Major, associating contralateral limited resection | 2 (3%) |

| Minor hepatectomy, n(%) | 25 (37.1%) |

| Segmentectomy/Bisegmentectomy | 17 (25.4%) |

| Limited resection | 7 (10.5%) |

| Left lateral bisegmentectomy | 1 (1.5%) |

| Lymphadenectomy | |

| YES | 23 (34.3%) |

| NO | 44 (65.7%) |

| Postoperative data | |

| Postoperative complications, n(%) | 32 (47.8%) |

| Clavien = b | 27 (40.3%) |

| Clavien > IIIA, n(%b | 5 (15.6%) |

| Complicated patients with lymphadenectomies | 15 (65.2%)c |

| Complicated patients without linfadenectomies | 17 (38.6%)c |

| Reoperation, n(%) | 4 (6%) |

| Postoperative mortality (90 days), n%) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Hospital stay (days), median (range) | 10 (5–100) |

| PATHOLOGICAL DATA | |

| Tumor size (cm), median (range) | 5.5 (1.4–15) |

| > 5 cm, n(%) | 44 (65.7%) |

| Tumor stage, n(%) | |

| IA | 3 (4.5%) |

| IB | 37 (55.2%) |

| II | 12 (17.9%) |

| IIIA | 3 (4.5%) |

| IIIB | 12 (17.9%) |

| Tumor differentiation, n(%) | |

| Well differentiated | 6 (9%) |

| Moderately differentiated | 50 (74.6%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 11 (16.4%) |

| Multifocal, n(%) | 6 (9%) |

| Vascular involvement, n(%) | 17 (25.4%) |

| Perineural involvement, n(%) | 14 (20.9%) |

| Lymphadenopathy involvement, n(%) | 10 (14.9%) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n(%) | 8 (11.9%) |

In 23 patients, 22 hilar-portal, 2 peripancreatic, 5 celiac trunk and 3 interaortocaval lymphadenectomies were performed. In 4 patients, resection of the left bile duct was associated with neoplastic invasion. Portal embolization was indicated prior to surgery in 4 patients, who were treated with right hepatectomy (2 cases), left hepatectomy and right trisectionectomy (one case each).

The median postoperative stay was 10 days (range: 5–100). Thirty-two patients (47.8%) presented some type of postoperative complication. Most (84.4%) were grades I to IIIa on the Clavien-Dindo scale9, predominantly surgical site infections that were treated with antibiotics, debridement in the patient’s hospital bed or percutaneous drainage with imaging techniques under local anesthesia. Five patients (3 Clavien IVa, 1 IVb and 1V) presented postoperative complications with respiratory, renal, or cardiac insufficiency that required surgical treatment and admission to the Intensive Care Unit. There was one case of perioperative mortality (Clavien V) due to sepsis and multiple organ failure. Out of the 23 patients who underwent lymphadenectomy, 15 (65.2%) presented complications, while only 17 of the 44 patients (38.6%) who did not have lymph node dissection presented them, which was a statistically significant result (P = .039) (Table 1).

In 80.6% of patients, resection was achieved with free margins (R0). Most of the patients (91.9%) had a single lesion. The median tumor size was 5.5 cm (1.4–15 cm), and in 44 patients the lesions were equal to or greater than 5 cm (65.7%). Seventeen patients had vascular invasion and 14 perineural invasion. In terms of tumor differentiation, most of the tumors (50 cases) were moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas, 6 were highly differentiated and 11 were poorly differentiated (Table 1).

Out of the 23 patients who underwent lymphadenectomy, 10 cases were positive (9 of the 22 hilar-portal lymphadenectomies [40.9%], one of the 2 peripancreatic dissections and one of the 3 interaortocaval lymphadenectomies. The 5 lymphadenectomies of the celiac trunk were negative.

In terms of staging, most patients (59.7%) presented stage IA or IB, 18% stage II, 4.5% stage IIIA, and 18% stage IIIB.

Two patients (4.5%) that were considered potentially resectable received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin-gemcitabine. Out of the 67 patients, 8 (11.9%) were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, 5 received gemcitabine, alone or in combination with 5-fluorouracil, 2 oxaliplatin-5 fluorouracil and one cisplatin-5-fluorouracil.

Thirty-nine patients (58.2%) presented some type of recurrence during follow-up, the majority (32 patients, 82.1%) in the form of liver recurrence. Out of the 7 remaining patients, the recurrence was pulmonary in one case, lymphadenopathy in 2, bone in 3, and various locations in one. Seventeen patients presented recurrence in more than one location. Only one case of the 32 liver recurrences (3.1%) was treated surgically with curative intent.

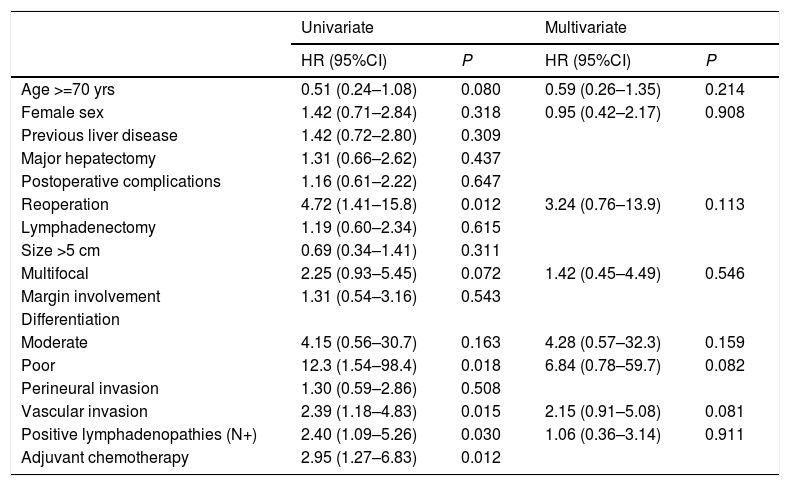

In the univariate analysis, reoperation, poorly differentiated tumors, positive lymphadenopathies, vascular invasion, and adjuvant chemotherapy were statistically significant. In the multivariate analysis, no variable showed statistical significance (Table 2).

Factors for risk of recurrence.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age >=70 yrs | 0.51 (0.24–1.08) | 0.080 | 0.59 (0.26–1.35) | 0.214 |

| Female sex | 1.42 (0.71–2.84) | 0.318 | 0.95 (0.42–2.17) | 0.908 |

| Previous liver disease | 1.42 (0.72–2.80) | 0.309 | ||

| Major hepatectomy | 1.31 (0.66–2.62) | 0.437 | ||

| Postoperative complications | 1.16 (0.61–2.22) | 0.647 | ||

| Reoperation | 4.72 (1.41–15.8) | 0.012 | 3.24 (0.76–13.9) | 0.113 |

| Lymphadenectomy | 1.19 (0.60–2.34) | 0.615 | ||

| Size >5 cm | 0.69 (0.34–1.41) | 0.311 | ||

| Multifocal | 2.25 (0.93–5.45) | 0.072 | 1.42 (0.45–4.49) | 0.546 |

| Margin involvement | 1.31 (0.54–3.16) | 0.543 | ||

| Differentiation | ||||

| Moderate | 4.15 (0.56–30.7) | 0.163 | 4.28 (0.57–32.3) | 0.159 |

| Poor | 12.3 (1.54–98.4) | 0.018 | 6.84 (0.78–59.7) | 0.082 |

| Perineural invasion | 1.30 (0.59–2.86) | 0.508 | ||

| Vascular invasion | 2.39 (1.18–4.83) | 0.015 | 2.15 (0.91–5.08) | 0.081 |

| Positive lymphadenopathies (N+) | 2.40 (1.09–5.26) | 0.030 | 1.06 (0.36–3.14) | 0.911 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 2.95 (1.27–6.83) | 0.012 | ||

The median follow-up was 28 months (range: 1.3–200.6), and the median survival was 31.2 months (95% CI: 22.2–65.1 months) (91.0%, 49.2% and 39.8% after 12, 36 and 60 months, respectively).

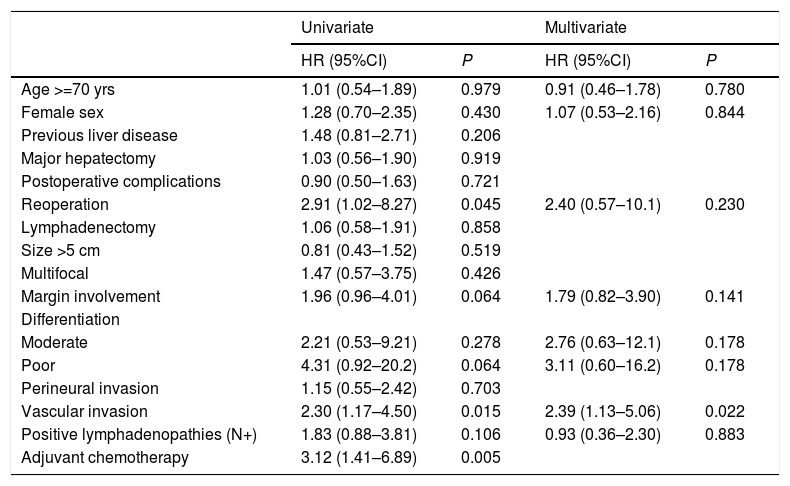

The univariate analysis of risk factors for survival showed that reoperation, vascular invasion, and adjuvant chemotherapy were significant variables. In the multivariate analysis, only vascular invasion was statistically significant (Table 3).

Risk factors for survival.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age >=70 yrs | 1.01 (0.54–1.89) | 0.979 | 0.91 (0.46–1.78) | 0.780 |

| Female sex | 1.28 (0.70–2.35) | 0.430 | 1.07 (0.53–2.16) | 0.844 |

| Previous liver disease | 1.48 (0.81–2.71) | 0.206 | ||

| Major hepatectomy | 1.03 (0.56–1.90) | 0.919 | ||

| Postoperative complications | 0.90 (0.50–1.63) | 0.721 | ||

| Reoperation | 2.91 (1.02–8.27) | 0.045 | 2.40 (0.57–10.1) | 0.230 |

| Lymphadenectomy | 1.06 (0.58–1.91) | 0.858 | ||

| Size >5 cm | 0.81 (0.43–1.52) | 0.519 | ||

| Multifocal | 1.47 (0.57–3.75) | 0.426 | ||

| Margin involvement | 1.96 (0.96–4.01) | 0.064 | 1.79 (0.82–3.90) | 0.141 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Moderate | 2.21 (0.53–9.21) | 0.278 | 2.76 (0.63–12.1) | 0.178 |

| Poor | 4.31 (0.92–20.2) | 0.064 | 3.11 (0.60–16.2) | 0.178 |

| Perineural invasion | 1.15 (0.55–2.42) | 0.703 | ||

| Vascular invasion | 2.30 (1.17–4.50) | 0.015 | 2.39 (1.13–5.06) | 0.022 |

| Positive lymphadenopathies (N+) | 1.83 (0.88–3.81) | 0.106 | 0.93 (0.36–2.30) | 0.883 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 3.12 (1.41–6.89) | 0.005 | ||

The median disease-free survival was 24.7 months (95% CI: 15.6–88.9 months) (67.2%, 32.8% and 22.4% after 12, 36, and 60 months, respectively) (Figs. 1 and 2).

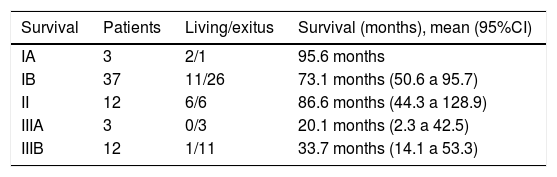

Regarding tumor stage, greater overall survival was observed in stages IA, IB and II (95.6, 73.1 and 86.6 months), which were statistically significant differences (P = .046). In the same way, greater disease-free survival was observed in stages IA and IB (72.5 and 111 months), also with significant differences (P = .024) (Table 4).

Risk factors for survival and recurrence according to stage.

| Survival | Patients | Living/exitus | Survival (months), mean (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA | 3 | 2/1 | 95.6 months |

| IB | 37 | 11/26 | 73.1 months (50.6 a 95.7) |

| II | 12 | 6/6 | 86.6 months (44.3 a 128.9) |

| IIIA | 3 | 0/3 | 20.1 months (2.3 a 42.5) |

| IIIB | 12 | 1/11 | 33.7 months (14.1 a 53.3) |

| Recurrence | Patients | Recurrence/no recurrence | Survival (months), mean (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA | 3 | 1/2 | 72.5 months (40.5–104.5) |

| IB | 37 | 17/20 | 111.1 months (79.8–142.3) |

| II | 12 | 8/4 | 42.4 months (20.4–64.4) |

| IIIA | 3 | 3/0 | 17.9 months (4.0–39.7) |

| IIIB | 12 | 10/2 | 24.8 months (3.8–45.9) |

Out of the 20 patients alive at the time of analysis, 18 are disease free. During follow-up, 47 patients died, 37 from recurrence of the cholangiocarcinoma and another 10 due to other causes, with no evidence of recurrence.

DiscussionIntrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is a primary hepatic neoplasm with a poor prognosis. The only potentially curative treatment is complete surgical resection. Improved surgical techniques and postoperative management have helped reduce the morbidity and mortality of the procedure.

The main objective of this study was to observe the influence on recurrence and patient survival of different factors that have been associated with poor prognosis in previous publications.

Overall survival was 91%, 49.2% and 39.8% after 12, 36, and 60 months, respectively, while disease-free survival was 67.2%, 32.8% and 22.4%, which is comparable to and even slightly longer than the rates obtained by other publications11–14. The median disease-free survival was 26.5 months, similar to the study by Endo et al.13

Postoperative morbidity in the form of reoperation has been shown to influence survival and recurrence as an independent variable. As for the pathological variables, tumor size, number of tumors (multifocality), tumor differentiation, vascular involvement and perineural involvement are determining factors for patient prognosis. Tumor size >5 cm (which was a determining factor in other publications13,15) did not demonstrate statistical significance in this study, nor did perineural invasion. Multifocality (found in only 8.95% of the cases in our series) also did not show significant differences, unlike the study by Endo et al.13 In contrast, vascular invasion turned out to be the most important risk factor affecting survival, as it was the only one that reached a statistically significant value in the multivariate analysis.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated in patients with poor prognostic factors, such as positive lymphadenopathies, invasion of surgical margins, or multifocal presentation. In this study, chemotherapy has been shown to be a variable that negatively influences survival and recurrence, a fact that could be explained by the presence of other factors that confer a poor prognosis, although the few cases in this series and the heterogeneity of the treatment do not allow us to draw conclusions. Even so, adjuvant chemotherapy is expected to increase the survival of resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the future, and it will be indicated in tumors with high risk factors for recurrence16. On the other hand, recent studies have linked intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with several genetic mutations and molecular changes, suggesting that immunotherapy and treatments targeted against these mutations will acquire relevance for the therapeutic approach to this neoplasm in the near future17,18.

Regarding the preoperative diagnosis and the need for diagnostic biopsy, it is recommended to follow the latest clinical guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)19. As for the need for systematic lymphadenectomy in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma surgery, this indication has evolved over time. A decade ago, some authors recommended the need for systematic lymphadenectomy to adequately stage patients20. Other authors have not been able to demonstrate any benefits, since survival was similar with or without lymphadenectomy21,22. In our series, it was applied to a third of the patients, and this was accompanied by greater morbidity, which may influence the decision to perform lymphadenectomy systematically. However, the NCCN guidelines recommend considering lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilum for better staging19.

Limitations of this study include the difficult data collection, especially in the initial period. In addition, certain results must be interpreted with caution, as there are only 3 cases in some sections (such as stages IA and IIIA). Surgical data and all resection specimens have been reviewed thoroughly, and the classification has been updated. However, patients diagnosed with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma that was considered unresectable or with comorbidities that contraindicated surgical intervention were not included. This information would have allowed us to know the evolution of the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, as well as the resectability index of this disease in our setting, as shown by other authors in their publications23,24.

As for prospects for the future, besides immunotherapy and therapy targeted against mutations, there are several factors to consider: the possibility of liver transplantation in selected patients with small and well-differentiated tumors, and the improved results of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in trials that are underway25.

To conclude, in terms of the surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, lymphadenectomy has led to greater morbidity, while vascular involvement in the pathological study has been the most important risk factor affecting survival.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank Mr Antoni Molera Espelt for his collaboration with data collection and updating.

Please cite this article as: Rafecas A, Torras J, Fabregat J, Lladó L, Secanella L, Busquets J, et al. Colangiocarcinoma intrahepático: factores pronósticos de recidiva y supervivencia en una serie de 67 pacientes tratados quirúrgicamente en un solo centro. Cir Esp. 2021;99:506–513.