Malignant tumors in the umbilical region are uncommon, although they represent more than 10% of malignant neoplasms that affect the skin of the anterior wall of the abdomen.1 This anatomical region is home to numerous vascular and embryological connections with the abdominal organs, which favors the appearance of metastases derived from different visceral tumors.2–4 Nonetheless, primary umbilical tumors make up only 20% of the malignant tumors in that location, and very few cases have been reported to date.3,5

We report the diagnostic/therapeutic sequence followed in a patient with a primary adenocarcinoma in the umbilical region, and also review the limited related scientific literature.

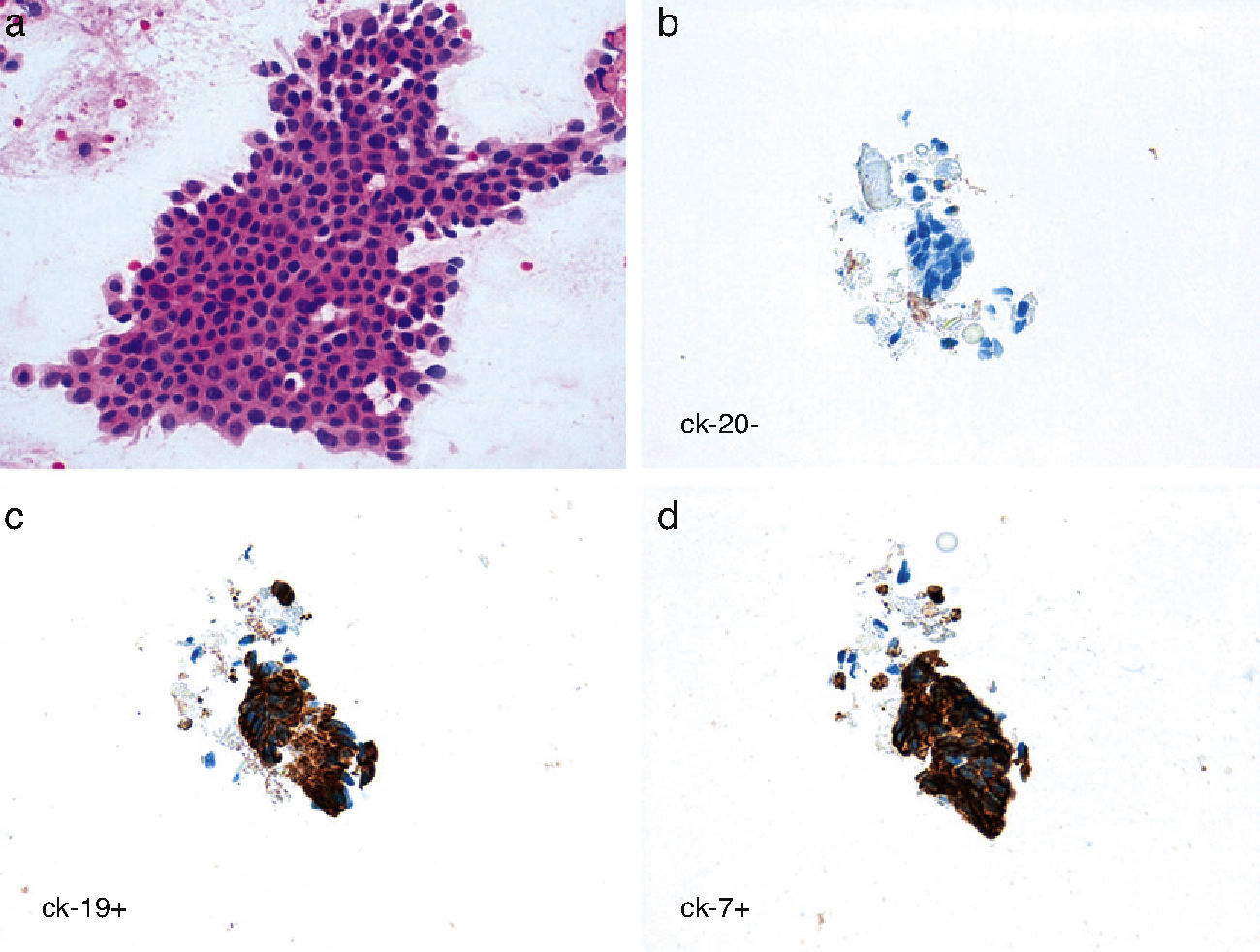

The patient was a 60-year-old male who presented with a painless non-reducible nodule in the umbilical region that had been progressively growing over the course of the previous year. Upon physical examination, we observed a round tumor formation that was attached to deep planes and measured some 3cm in diameter. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a solid umbilical mass measuring 3cm×2cm affecting the left anterior rectus. The fine needle aspiration (FNA) sample was compatible with adenocarcinoma. The cytology report, including immunohistochemistry study, showed a possible biliopancreatic origin as the first option and proposed that the lesion could possibly be a primary umbilical adenocarcinoma if no other origin was found (Fig. 1). The patient underwent gastroscopy, colonoscopy, thoracic and abdominal computed axial tomography (CT) scans (Fig. 2), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and even positron-emission tomography (PET) with the intention to rule out the presence of a primary tumor in another location. All of the tests came back normal.

We performed a midline laparotomy with en bloc resection of the navel, tumor and a portion of the left anterior rectus muscle that was affected. We explored the rest of the abdominal cavity, with normal findings. Postoperative recovery was favorable, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 48h after the intervention. The pathology study reported findings compatible with well-differentiated infiltrating adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3). As no internal adenocarcinoma was found, it was concluded that the mass was a primary umbilical adenocarcinoma arising from the urachus. Seven months after the intervention, the patient is asymptomatic, with normal tumor marker levels and no evidence of locoregional or distant disease.

Microscopic study of the surgical specimen: (a) a neoplasm is observed composed of glandular structures with a tendency toward cystification without significant signs of complexity, covered for the most part by a cuboidal, cylindrical or (less frequently) flat epithelial monolayer. The cells show mild cytological atypia with a limited number of mitoses. In the lumen of the glands, there is presence of a material with proteinaceous content (asterisk). The stroma surrounding the gland structures is intensely desmoplastic (arrow), and some lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate is also observed, sometimes with formation of clear centers (two arrows) (HE, 50×); (b) the proliferation rate (ki-67) was approximately 30%.

The navel region can be a host to a large variety of benign tumors.3,6 Malignant tumors, which are much less frequent, are mostly metastases of an abdominal neoplasm and, to a lesser degree, they can be primary umbilical tumors, representing only 20% of malignant tumors of the navel. They are mainly adenocarcinomas although other histologic types, such as sarcomas and melanomas, have also been described. The glandular epithelium is normally not present in the umbilical area, but it can appear derived from the metaplasia of the squamous epithelium or embryological remains of the omphalomesenteric duct or the urachus.2,3,6–8

Therefore, given an umbilical nodule with histological characteristics of adenocarcinoma in an FNA sample, the main problem is determining the origin. Immunohistochemistry can guide the diagnosis, but it is essential to complete a series of tests to rule out the existence of an extra-umbilical primary tumor (thyroid ultrasound, abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT scan, colonoscopy, chest radiography, etc.).3,4 In our case, we also carried out a PET and a gastroscopy, since gastric adenocarcinoma is the tumor that most frequently metastasizes in the navel.9,10

Metastases of other tumors in the navel are known as “Sister Mary Joseph nodules” and are found in from 1 to 3% of digestive tumors.9,10 The embryological connection between this region and the abdominal organs, as well as the extensive lymphatic network that connects the navel with the inguinal and axillary areas, explains this predisposition. The primary tumor is usually found in the gastro-intestinal tract (stomach, pancreas, intestine, cecal appendix, etc.) although they may also be gynecological tumors, sarcomas and other neoplasms originating outside the abdominal cavity (breast, lung, penis).1–3,5,6

Treatment of primary tumors of the navel is radical resection.3 During surgery, all the abdominal organs should be examined, as in our case, in order to rule out the existence of a primary tumor that had not been detected previously. Besides complete resection of the tumor, it is necessary to follow-up these patients since relapse in the umbilical area has been reported in the literature3,4 as well as the later appearance of liver metastases3 and lymphadenopathies in the inguinal region4 in the mid- and long-terms. This could indicate the need for adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy in certain patients. Because of their poor prognosis, the treatment of metastatic umbilical tumors is more controversial, and radiotherapy is the treatment of choice in many cases.3

In conclusion, tumors in the umbilical region require a differential diagnosis in which it is essential to carry out a series of tests to rule out the existence of an extra-umbilical primary tumor, which can vary the therapy to be followed. There are few cases described in the literature of primary malignant neoplasms affecting the umbilicus, and it is therefore necessary to study each case in detail and to closely follow up the patients after they have been treated surgically since the prognosis is still not well defined.

Please cite this article as: Febrero B, Ruiz de Angulo D, Ortiz MÁ, López MJ, Parrilla P. Adenocarcinoma primario del ombligo: una entidad poco frecuente. Cir Esp. 2014;92(6):436–438.