The liver is the organ of the abdominal cavity that is most affected by both penetrating and blunt abdominal trauma. Up to 85% of patients suffering from blunt liver trauma may be candidates for conservative treatment. Nonsurgical management has led to a decrease in mortality, although this approach may give rise to a considerable number of complications.

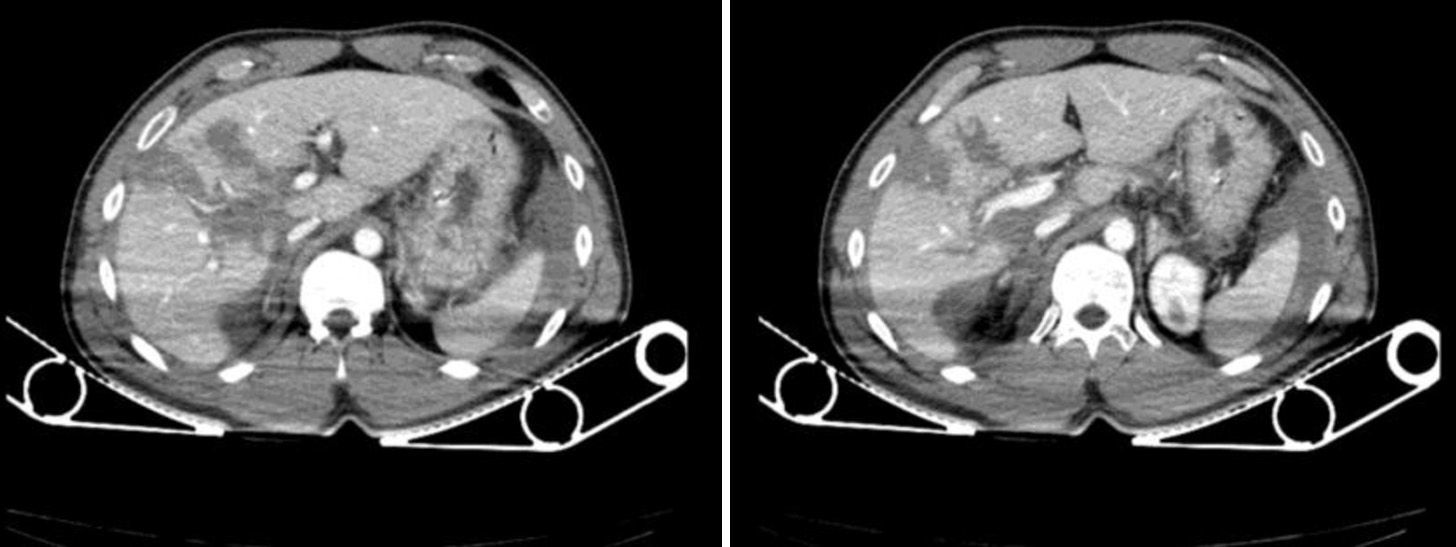

We present the case of a 34-year-old male who had sustained multiple injuries in a motorcycle accident. Eco-FAST upon admission showed free fluid in the abdomen. Since the patient was hemodynamically stable, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed (Fig. 1).

The patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit and remained hemodynamically stable. On the 5th day, abdominal ultrasound showed reorganization of the parenchymal hematoma and extensive free fluid. Intra-abdominal pressure increased progressively, reaching 36mmHg on the 10th day of hospitalization. Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels were stable, although leukocyte and PCR levels were high. Abdominal tomography demonstrated a significant increase in the amount of free fluid in the abdomen. Paracentesis was performed, and a choleperitoneum was diagnosed.

Emergency laparotomy confirmed the choleperitoneum, without revealing the origin of the bile leak after the administration of methylene blue through a cannula into the gallbladder. There was no disruption of the parenchyma. We proceeded with lavage and drainage, and a 400 cc biliary fistula became evident within the first 24h.

ERCP was performed, which showed a non-dilated bile duct with extravasation of contrast at the proximal right hepatic duct, which quickly passed to the subhepatic bed and the abdominal drainage catheter. A 7Fr/12cm plastic prosthesis was inserted distal to the lesion.

The fistula output volume decreased to 200 cc in 24h and remained without change on successive days. Thus, we decided on performing another ERCP, with decreased leak from the proximal right hepatic duct. A plastic 8.5Fr/10cm prosthesis was inserted. After this procedure, there was no bile output through the subhepatic drain.

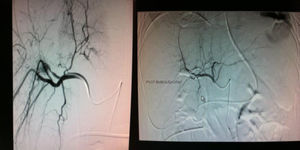

On the 28th day of hospitalization, the patient started to have bloody discharge through the nasogastric tube and hyperbilirubinemia (5mg/dl). Upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy revealed a clot from the second portion of the duodenum suggestive of hemobilia and biliary stent migration. A nasobiliary drainage catheter (7Fr) was inserted. Bleeding persisted, causing hemodynamic instability, and angiography was performed (Fig. 2).

After a few days, the patient started to have pain in the right hypochondrium, fever and leukocytosis. CT scan revealed an intraparenchymal abscess in segment VI that measured 7cm×7.5cm. Percutaneous drainage confirmed the diagnosis of infected biloma. A new ERCP revealed an intraparenchymatous leak in the right lobe. A plastic prosthesis was placed (8.5Fr and 10cm). The drainage catheter was withdrawn on the 7th day.

Between 2.8% and 7.4% of patients treated with conservative management of liver trauma develop biliary complications.1 When peritoneal irritation is suspected, CT is the diagnostic technique of choice in hemodynamically-stable abdominal trauma.2,3 In cases with inconclusive findings, diagnostic paracentesis or diagnostic peritoneal lavage may clarify the diagnosis.4

In patients with high-grade liver injuries that are managed conservatively, CT should be repeated 7–10 days after hospitalization; the repetition of this test is unnecessary in low-grade lesions (I-II-III AAST).5

The presence of a well-defined lesion with low attenuation suggests a biloma, which could be managed conservatively in most cases, or with percutaneous drainage if symptomatic (<1%).4

In those cases in which a biliary fistula develops, ERCP with biliary stent placement can achieve a resolution rate of 90%–100% of cases.6–8 Biliary stents have been shown to be superior to sphincterotomy in several published studies.1

The presence of choleperitoneum and high intra-abdominal pressure require drainage of the abdominal cavity. One wonders whether abdominal percutaneous drainage would have been enough, although this option was ruled out in this case because of the time of development and the inability to determine associated injuries. Could laparoscopy have been a valid alternative? The answer is yes: the value of diagnostic laparoscopy in blunt abdominal trauma remains to be defined, but in selected patients it may contribute to the diagnosis and to performing therapeutic procedures.4

As for the prevalence of delayed bleeding during conservative management of closed liver trauma, this is seen in between 1.7% and 5.9% of cases and is usually associated with infectious liver complications or the formation of aneurysms.1 Arteriography is the method of choice for hemobilia. Mohr et al. studied the complications that appear after angioembolization and found a rate of morbidity approaching 58%; biliary fistula, hepatic abscess and ischemic necrosis were the most frequent processes.9 The combination of liver trauma and ischemic necrosis predisposes the patient to biliary complications.1

Please cite this article as: Casado Maestre MD, Bengoechea Trujillo A, Lizandro Crispín A, Rodríguez Ramos C, Fernández Serrano JL. Complicaciones en el manejo conservador del traumatismo hepático cerrado: fístula biliar, hemobilia y biloma. Cir Esp. 2013;91:537–539.