Enhanced recovery after surgery is a modality of perioperative management with the purpose of improving results and providing a faster recovery of patients. This kind of protocol has been applied frequently in colorectal surgery, presenting less available experience and evidence in gastric surgery.

MethodsAccording to the RICA guidelines published in 2015, a review of the bibliography and the consensus established in a multidisciplinary meeting in Zaragoza on the 9th of October 2015, we present a protocol that contains the basic procedures of fast-track for resective gastric surgery.

ResultsThe measures to be applied are divided in a preoperative, perioperative and postoperative stage. This document provides recommendations concerning the appropriate information, limited fasting and administration of carbohydrate drinks 2h before surgery, specialized anesthetic strategies, minimal invasive surgery, no routine use of drainages and tubes, mobilization and early oral tolerance during the immediate postoperative period, as well as criteria for discharge.

ConclusionsThe application of a protocol of enhanced recovery after surgery in resective gastric surgery can improve and accelerate the functional recovery of our patients, requiring an appropriate multidisciplinary coordination, the evaluation of obtained results with the application of these measures and the investigation of controversial topics about which we currently have limited evidence.

La rehabilitación multimodal es un conjunto de medidas que se aplican durante el período perioperatorio con el fin de mejorar los resultados y facilitar una pronta recuperación de los pacientes. La aplicación de protocolos de este tipo se ha extendido ampliamente en la cirugía colorrectal, siendo menor la experiencia y evidencia disponible en relación con la cirugía gástrica.

MétodosEn base a las directrices marcadas por la vía Recuperación Intensificada en Cirugía Abdominal (RICA) publicada en el año 2015, una amplia revisión de la bibliografía y el consenso establecido en una reunión multidisciplinar del Grupo de Trabajo de Cirugía Esofagogástrica del Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal celebrada en Zaragoza el 9 de octubre de 2015, se presenta una matriz temporal que recoge las recomendaciones fundamentales para la aplicación de un protocolo de rehabilitación multimodal en la cirugía de resección gástrica.

ResultadosLas medidas a aplicar se dividen en una etapa preoperatoria, otra perioperatoria y otra postoperatoria. Así, se establecen en este documento recomendaciones sobre la información adecuada y preparación del paciente y su entorno, el ayuno limitado y la ingesta de bebidas carbohidratadas 2h antes de la operación, estrategias anestésicas más especializadas, la cirugía mínimamente invasiva, la no colocación de forma sistemática de sondas o drenajes, la movilización y tolerancia oral precoz durante el postoperatorio inmediato, así como los criterios a considerar para el alta hospitalaria.

ConclusionesLa aplicación de un protocolo de rehabilitación multimodal en la cirugía resectiva gástrica puede mejorar y acelerar la recuperación funcional de nuestros pacientes. Sin embargo, para conseguir este objetivo se precisa de una correcta coordinación multidisciplinar, así como de la evaluación de los resultados y del análisis e investigación de los puntos de controversia sobre los que la evidencia científica es aún limitada.

Multimodal Rehabilitation (MMR) or Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) programs have been developed as an approach to all aspects of patient care in order to provide the best and fastest recovery possible. In this context, less aggressive surgical techniques and advances in anesthetic management, pain control and specific perioperative care have shown clear benefits in postoperative recovery.1 Kehlet and Wilmore2 were the first to propose and apply a series of measures of this type after colorectal surgery within a fast-track MMR program. In our country, the Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group (Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal – GERM) was created in 2007. In close collaboration with the Ministry of Health, Social Affairs and Equality, in 2015 GERM published the Intensified Recovery in Abdominal Surgery (IRAS) guidelines,3 which provides an evidence-based protocol for the stages and key points of MMR in the perioperative management of patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

To date, the greatest implementation of these protocols has been in colorectal surgery. However, given the excellent results obtained in this type of surgery, it seems logical to try to extend its application to other types of major abdominal surgery.4–7 With regards to gastric resection surgery, there are few high-quality studies that provide demonstrated evidence from intensified recovery protocols, although there is growing evidence of its safety and benefits compared to more traditional management.8

This manuscript presents an MMR protocol or time management matrix for gastric resection surgery that was developed and approved by members of GERM based on a thorough review of currently available evidence and the clinical experience of a multidisciplinary group of experts.

MethodsThe work group that developed this protocol included a total of 42 medical professionals from different specialties and hospitals (32 surgeons, 5 anesthetists, 3 nurses and 2 nutritionists) with accredited experience in the treatment of patients with gastric disease. The result was a time matrix, whose final version was agreed upon at a consensus meeting held in Zaragoza, Spain, on October 9, 2015.

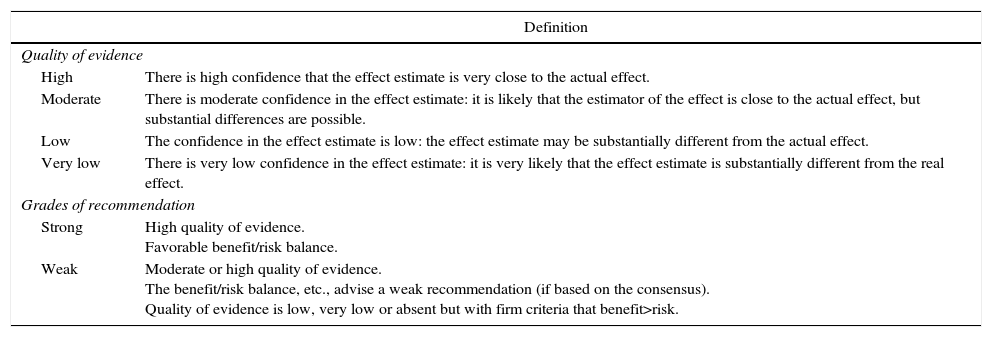

This protocol was established based on general recommendations established in the IRAS3 for abdominal surgeries, an extensive bibliographic search on MMR in gastric surgery in the Cochrane Library, Medline, EMBASE, Scopus, Tryp database and DARE from 1995 to 2015, and the opinion and consensus of the group of experts. The results obtained from the bibliographic search were evaluated using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) methodology, establishing the levels of quality of evidence and the grade of recommendation according to the GRADE system9 (Table 1).

Quality of Evidence and Degrees of Recommendation According to the GRADE Methodology.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Quality of evidence | |

| High | There is high confidence that the effect estimate is very close to the actual effect. |

| Moderate | There is moderate confidence in the effect estimate: it is likely that the estimator of the effect is close to the actual effect, but substantial differences are possible. |

| Low | The confidence in the effect estimate is low: the effect estimate may be substantially different from the actual effect. |

| Very low | There is very low confidence in the effect estimate: it is very likely that the effect estimate is substantially different from the real effect. |

| Grades of recommendation | |

| Strong | High quality of evidence. Favorable benefit/risk balance. |

| Weak | Moderate or high quality of evidence. The benefit/risk balance, etc., advise a weak recommendation (if based on the consensus). Quality of evidence is low, very low or absent but with firm criteria that benefit>risk. |

Adapted by Guyatt et al.9

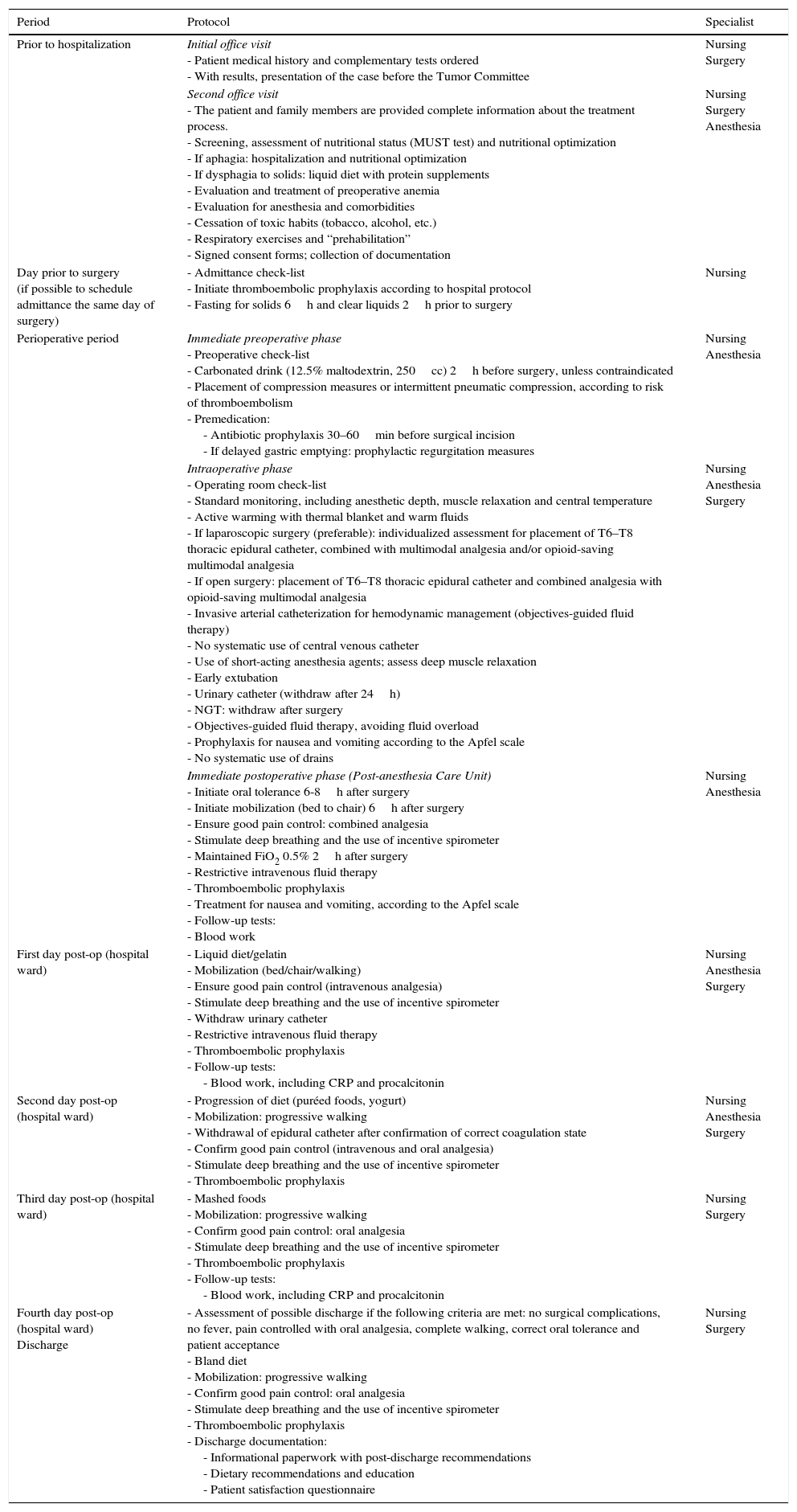

This document presents a multidisciplinary protocol for all the measures to be carried out in the perioperative management of patients with gastric disease who are candidates for resective surgery under the MMR approach. It establishes the indications and recommendations to be considered in each stage of the treatment process. Thus, in order to facilitate the overall comprehension and outline of the protocol (Addendum 1), the actions will be grouped in 3 stages: preoperative, perioperative and postoperative. Obviously, these recommendations and measures should be applied at each hospital in a rational, progressive, individual or global manner and based on the specific resources available and protocols of each institution.

ResultsIndications and ContraindicationsCandidates for the application of the recommended measures were those patients who were scheduled for total, partial or subtotal gastrectomy (ICD-9 codes: 43.5, 43.6, 43.7, 43.81, 43.89, 43.91, 43.99) and met the following criteria3:

- –

Age between 18 and 85.

- –

Appropriate cognitive state (able to comprehend and cooperate).

- –

ASA I, II and II.

Excluded from the application of this protocol were pediatric patients and those requiring urgent surgery.

Protocol and Time Matrix (Addendum 1)Preoperative PeriodIn this period, among other measures included in the protocol, the following points should be highlighted:

- -

Detailed oral and written information should be provided about the entire process, as it is able to reduce fear, favor early oral intake and improve recovery, mobilization, pain control and respiratory function (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).10,11

- -

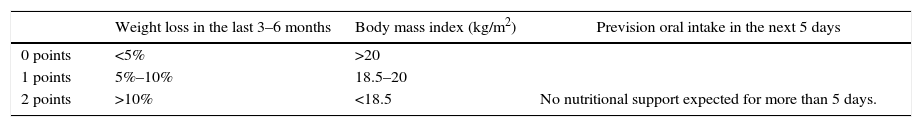

Evaluation and optimization of nutritional status: all patients who are scheduled to undergo this type of surgery should be evaluated by nutritionists and follow certain nutritional recommendations in order to optimize and ensure proper nutritional status, especially in those who present a certain degree of dysphagia (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).12,13 There are many scales developed to assess nutritional status and risk of malnutrition, and one of the most widely used is the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST).14Table 2 shows an adaptation of this tool for use in patients who are candidates for the application of this protocol. The use of artificial nutrition is considered indicated in cases of severe malnutrition for a period of 10–14 days before surgery (Recommendation: strong. Level of evidence: high).15,16

Table 2.Adapted Model of the Evaluation of the Nutritional Status and Risk for Malnutrition (Based on the MUST Model).

Weight loss in the last 3–6 months Body mass index (kg/m2) Prevision oral intake in the next 5 days 0 points <5% >20 1 points 5%–10% 18.5–20 2 points >10% <18.5 No nutritional support expected for more than 5 days. Calculation of the risk for malnutrition 0=Low risk 1=Moderate risk 2=High risk Standard clinical management

Repeat screening:

- Hospital: every week

- Residences: at least every month

- Community: every year in special groupsDocument dietary intake in 3 days:

If intake is sufficient: repeat the screening

- Hospital: every week

- Residences: at least every week

- Community: at least every 2–3 months

If intake is insufficient: follow local protocols, set objectives, improve and increase the total nutritional intake, follow-up and review periodicallyInitiate supplemental artificial nutrition and/or consult with the hospital nutritional support unit. Refer to a dietitian or nutritional support team, or apply local protocols.

Set objectives, improve and increase total nutritional support.Adapted from Stratton et al.14

- -

Evaluation and treatment of preoperative anemia: The aim is to achieve preoperative hemoglobin values of more than 13g/dL in men and 12g/dL in women, according to the recommendations of the World Health Organization (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: high).3,17,18

- -

Cessation of toxic habits and prehabilitation: Alcohol abuse (defined as an intake greater than 36g ethanol per day) is associated with an increased risk of bleeding, surgical wound infection, and metabolic response to stress. A minimum abstinence of 4 weeks before surgery is necessary to reduce this risk. Furthermore, smoking has been shown to increase pulmonary complications by up to 50%, and cessation 4 weeks before surgery improves surgical wound healing. Therefore, it is recommended to stop alcohol use and smoking at least 4 weeks prior to surgery (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate)19,20; meanwhile, moderate physical exercise, breathing exercises and various prehabilitation therapies are recommended.21

In this period, we should highlight the following points in addition to other measures reflected in the protocol (Addendum 1):

- -

Preoperative diet and fasting: Patients should abstain from oral intake of solids 6h before surgery and clear liquids 2h before surgery (Recommendation: strong; level of evidence: moderate-high).22,23 The patient should also drink a carbonated drink (250mL with 12.5% maltodextrins) 2h before surgery. (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate-high).24,25 These measures reduce postoperative ileus, improve catabolic response and insulin resistance during the postoperative period, and should be applied individually and with caution in patients with certain degrees of dysphagia.

- -

Antibiotic and thromboembolic prophylaxis measures: Prophylactic antibiotic administration is recommended 30–60min before the surgical incision,26 and repeat doses are recommended in procedures longer than 3h or in cases of bleeding in excess of 1500mL (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: high).3,10,27 In addition, for thromboembolic prevention, the administration of low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended together with other measures, such as compression stockings or intermittent compression systems, based on the individualized risk of each patient (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).10,28 This prophylaxis should be continued for at least 7–10 days after surgery and extended for 4 weeks in high-risk patients.29

- -

Anesthetic care: the following anesthesia measures should be applied:

- ∘

Monitoring with capnography, central temperature control, diuresis, anesthetic depth and neuromuscular function (Recommendation: weak; Level of evidence: moderate).30–33

- ∘

Invasive catheterization is recommended for adequate objectives-guided fluid therapy, and placement of a central venous catheter is reserved for select cases.

- ∘

Analgesia should be opioid-saving multimodal analgesia, while the use of local anesthesia and the insertion of a thoracic epidural catheter (T6–T8) should be considered depending on the type of surgical approach (laparotomy or laparoscopic) and the individual need of each patient (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).34

- ∘

Short-acting anesthesia should be administered and premature extubation should be done in the operating room, if possible.

- ∘

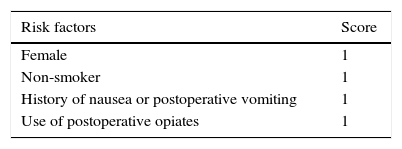

The presence of nausea and vomiting during the postoperative period can appear in about 30% of all surgical patients. It is the main cause of delayed initiation of oral tolerance, mobilization and hospital discharge. It is therefore recommended to evaluate the risk for developing this problem with the Apfel scale35 (Table 3) and, in patients at high risk, measures should be applied (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate) such as the use of propofol in anesthesia induction and maintenance,36 avoiding the use of nitrous oxide,37 the use of inhaled anesthesia38 and minimizing the use of intraoperative and postoperative opiates, prioritizing epidural analgesia.39,40

- ∘

Active warming of the patient is recommended with a thermal blanket and fluid warming in order to maintain body temperature and avoid hypothermia (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate-low).3,41,42

Surgical approach: Both laparoscopic and laparotomic approaches can be used in MMR protocols, depending on the experience of the surgical team and available resources. The laparoscopic approach involves smaller incisions, less surgical trauma and is usually accompanied by less hemorrhage, shorter hospital stay and faster return to daily activities while maintaining the safety of the laparotomic approach, which is why it is recommended whenever possible (Recommendation: weak; Level of evidence: moderate).43,44 As demonstrated by a meta-analysis published in 2015 with more than 400 patients who had undergone gastrectomy,45 the use of abdominal drains does not provide benefits in terms of postoperative morbidity and mortality and increases the time for initiation of oral intake and hospital stay. Therefore, the systematic use of drains is not recommended in these procedures (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate-high).45–47

The systematic use of a nasogastric tube is also not recommended and, if used, its withdrawal should be considered after the intervention is completed or in the first 24h after surgery (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate-high).48,49 A meta-analysis with more than 700 patients comparing the use or not of decompression catheters after gastric surgery concluded that there were no differences in postoperative morbidity and mortality or hospital stay, but the time to postoperative oral intake was shorter in the group where the catheter had not been used.50 The routine placement of parenteral feeding catheters or jejunostomies is also not recommended.

Immediate Postoperative PhaseDuring the initial postoperative hours, patients remain in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit or Postoperative Recovery Unit, taking into account the following aspects (Addendum 1):

- -

According to many MMR protocols, oral intake (clear liquids) should be initiated within a few hours of surgery, which entails no increase in complications. In addition, this measure facilitates the onset of peristalsis and postoperative recovery, so the ingestion of clear fluids is recommended 6–8h after surgery (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).10

- -

The use of flow and volume-oriented incentive spirometers is recommended during the postoperative period of these patients in order to reduce the number of associated respiratory complications (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).51 This measurement will be maintained throughout the postoperative period.

- -

All postoperative management guidelines agree on the beneficial effect of early mobilization after surgery (Recommendation: strong; Level of evidence: moderate).10 The available literature does not exactly specify the ideal time to start, although many studies recommend walking 6h after surgery,52,53 or at least transferring the patient to the armchair for 2h on the same day of surgery,54,55 or mobilization in bed 6h after the intervention.56 Therefore, although there is no unified criterion to define the timing, manner or duration of mobilization, it is generally recommended that active mobilization be initiated within the first 24h after surgery.

- -

Ensuring correct tissue oxygenation and good pain control through the use of combined analgesia (epidural catheter, intravenous analgesia, etc.) is essential for a good postoperative progress.

During the postoperative period, different measures are applied (Addendum 1) to attempt to progressively reestablish basic functions and return to the preoperative state. Among these measures, the following stand out:

- -

As previously mentioned, the early initiation of oral intake is recommended,10,53,57,58 resulting in a rapid return to correct gastrointestinal function and shorter hospital stay. It is advisable to proceed with caution according to patient tolerance, starting with a liquid diet and gelatin during the first postoperative day and progressively increasing to puréed foods/yogurt, mashed foods, and finally a soft diet on the fourth day post-op before discharge.

- -

Active and progressive mobilization is recommended, from sitting to progressive ambulation in time and distance during the first postoperative days.10

- -

Other strategies such as pain control, thromboembolic prophylaxis and breathing exercises, discussed above, should continue to be considered at this stage.

- -

Complementary tests: Follow-up analyses with blood count and basic biochemistry are recommended, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin on alternating days and depending on the patient's evolution (Recommendation: weak; Level of evidence: low). Systematic transit studies with contrast have not been shown to improve postoperative recovery (Recommendation: weak, Level of evidence: low),8 although there are groups with experience in this type of processes that perform it on the first53 or second day post-op.59

- -

In the absence of warning signs, hospital discharge may be assessed on the fourth day post-op in patients who meet the following criteria:

- 1.

Analgesia with oral medication.

- 2.

Correct ambulation and independence for basic daily activities.

- 3.

Good oral tolerance.

- 4.

Acceptance and proper comprehension of the discharge instructions and what to do in case of warning signs.

- 5.

Absence of warning signs to indicate suspicion.

MMR is an alternative to traditional management in patients undergoing gastrectomy. Scientific evidence shows that it facilitates postoperative recovery while reducing hospital stay and costs associated with the procedure. This manuscript presents an extensive review of the current literature and establishes recommendations based on it and the consensus established by experts from different fields (surgery, anesthesia, nursing and nutrition), thereby creating a time-based matrix that intends to serve as a guideline for the application of an MMR protocol in this type of surgery. However, one must consider the limited evidence available for some of the points discussed in this manuscript. Furthermore, most of the studies are based on series of Asian medical centers, where the management, tumor stage, and patient type differ to some degree from cases in our setting. In addition, the prevalence of gastric cancer in Western countries is not as high as in the East nor as high as colorectal cancer in our setting, so the possibilities of developing well-designed prospective studies with a large number of cases reporting consistent scientific evidence are more limited.

Obviously, the implementation of these measures should not be rigidly interpreted and should be adapted to the possibilities, organization and infrastructure of each hospital, although the joint application of most is recommended to favor better results. In addition, the multidisciplinary work of several specialists is necessary to obtain a well-structured and organized care sequence. The hospital staff should work together in the same global program, which would allow all facets of the process to happen more quickly and effectively.

For the development and fulfillment of all these measures, one of the basic pillars is to clearly inform the patient and family members, promoting self-care and involvement in surgical preparation and postoperative recovery. This information must be provided verbally and in writing because much verbal information is often forgotten; sometimes, less than 25% of information provided orally is recalled.60–62 It is also essential to provide patients with support material to be able to inform themselves and to consult whenever needed throughout the process, either before or after surgery and/or discharge.

The philosophy of MMR involves several points that are opposed to more traditional tendencies. Thus, measures such as limited fasting and the ingestion of a carbonated drink 2h before surgery, more specialized anesthetic strategies, minimally invasive surgery, mobilization and early oral tolerance during the immediate postoperative period, the indication and more restrictive placement of catheters and drains, etc., make for earlier patient recovery and better results than with the traditional approach. Along this line, a meta-analysis from 2015 of studies published up to 2014 on MMR in esophagogastric surgery (including 7 studies and a total of 329 patients with gastrectomy) observed that MMR protocols reduced hospitalization time in the Anesthesia Care Unit, time to oral intake and time to hospital discharge.8 In addition, morbidity and mortality results were similar to those of the traditional approach, with a lower percentage of readmissions (5%–10%), but without clear differences in other postoperative morbidity data. According to some studies, the percentage of reoperations was also similar to traditional management.52,63

One of the purposes of GERM is to periodically evaluate the results from applying these protocols and to update them, making revisions based on new scientific evidence, projects and research that attempt to resolve aspects that have yet to be clarified. Thus, the intention is to create a national registry to collect data associated with the implementation of these protocols and to evaluate the application percentage of the proposed measures as well as the compliance and feasibility of the implementation of these protocols.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

| Period | Protocol | Specialist |

|---|---|---|

| Prior to hospitalization | Initial office visit - Patient medical history and complementary tests ordered - With results, presentation of the case before the Tumor Committee | Nursing Surgery |

| Second office visit - The patient and family members are provided complete information about the treatment process. - Screening, assessment of nutritional status (MUST test) and nutritional optimization - If aphagia: hospitalization and nutritional optimization - If dysphagia to solids: liquid diet with protein supplements - Evaluation and treatment of preoperative anemia - Evaluation for anesthesia and comorbidities - Cessation of toxic habits (tobacco, alcohol, etc.) - Respiratory exercises and “prehabilitation” - Signed consent forms; collection of documentation | Nursing Surgery Anesthesia | |

| Day prior to surgery (if possible to schedule admittance the same day of surgery) | - Admittance check-list - Initiate thromboembolic prophylaxis according to hospital protocol - Fasting for solids 6h and clear liquids 2h prior to surgery | Nursing |

| Perioperative period | Immediate preoperative phase - Preoperative check-list - Carbonated drink (12.5% maltodextrin, 250cc) 2h before surgery, unless contraindicated - Placement of compression measures or intermittent pneumatic compression, according to risk of thromboembolism - Premedication: - Antibiotic prophylaxis 30–60min before surgical incision - If delayed gastric emptying: prophylactic regurgitation measures | Nursing Anesthesia |

| Intraoperative phase - Operating room check-list - Standard monitoring, including anesthetic depth, muscle relaxation and central temperature - Active warming with thermal blanket and warm fluids - If laparoscopic surgery (preferable): individualized assessment for placement of T6–T8 thoracic epidural catheter, combined with multimodal analgesia and/or opioid-saving multimodal analgesia - If open surgery: placement of T6–T8 thoracic epidural catheter and combined analgesia with opioid-saving multimodal analgesia - Invasive arterial catheterization for hemodynamic management (objectives-guided fluid therapy) - No systematic use of central venous catheter - Use of short-acting anesthesia agents; assess deep muscle relaxation - Early extubation - Urinary catheter (withdraw after 24h) - NGT: withdraw after surgery - Objectives-guided fluid therapy, avoiding fluid overload - Prophylaxis for nausea and vomiting according to the Apfel scale - No systematic use of drains | Nursing Anesthesia Surgery | |

| Immediate postoperative phase (Post-anesthesia Care Unit) - Initiate oral tolerance 6-8h after surgery - Initiate mobilization (bed to chair) 6h after surgery - Ensure good pain control: combined analgesia - Stimulate deep breathing and the use of incentive spirometer - Maintained FiO2 0.5% 2h after surgery - Restrictive intravenous fluid therapy - Thromboembolic prophylaxis - Treatment for nausea and vomiting, according to the Apfel scale - Follow-up tests: - Blood work | Nursing Anesthesia | |

| First day post-op (hospital ward) | - Liquid diet/gelatin - Mobilization (bed/chair/walking) - Ensure good pain control (intravenous analgesia) - Stimulate deep breathing and the use of incentive spirometer - Withdraw urinary catheter - Restrictive intravenous fluid therapy - Thromboembolic prophylaxis - Follow-up tests: - Blood work, including CRP and procalcitonin | Nursing Anesthesia Surgery |

| Second day post-op (hospital ward) | - Progression of diet (puréed foods, yogurt) - Mobilization: progressive walking - Withdrawal of epidural catheter after confirmation of correct coagulation state - Confirm good pain control (intravenous and oral analgesia) - Stimulate deep breathing and the use of incentive spirometer - Thromboembolic prophylaxis | Nursing Anesthesia Surgery |

| Third day post-op (hospital ward) | - Mashed foods - Mobilization: progressive walking - Confirm good pain control: oral analgesia - Stimulate deep breathing and the use of incentive spirometer - Thromboembolic prophylaxis - Follow-up tests: - Blood work, including CRP and procalcitonin | Nursing Surgery |

| Fourth day post-op (hospital ward) Discharge | - Assessment of possible discharge if the following criteria are met: no surgical complications, no fever, pain controlled with oral analgesia, complete walking, correct oral tolerance and patient acceptance - Bland diet - Mobilization: progressive walking - Confirm good pain control: oral analgesia - Stimulate deep breathing and the use of incentive spirometer - Thromboembolic prophylaxis - Discharge documentation: - Informational paperwork with post-discharge recommendations - Dietary recommendations and education - Patient satisfaction questionnaire | Nursing Surgery |

María Asunción Acosta Mérida, María Dolores Alonso Herreros, Rosario Aparicio Sánchez, Laura Armañanzas Ruiz, Carmen Balagué Ponz, Helena Benito Naverac, José A. Casimiro Pérez, José María Calvo Vecino,Vanessa Concepción Martín, Roberto de la Plaza Llamas, Marta de Vega Irañeta, Carlos J. Díaz Lara, Ismael Diez del Val, María del Lluch Escudero Pallardó, Mónica García Aparicio, Francisca García-Moreno Nisa, Lorena Gómez Diago, María Luz Herrero Bogajo, Yolanda López Revuelta, Rafael López Pardo, Ezequiel Martí-Bonmatí, Javier Martín Ramiro, José Martínez Guillén, Luis Enrique Muñoz Alameda, Inmaculada Navarro García, Ana Cristina Navarro Gonzalo, Julia Ocón Bretón, María Posada González, Pablo Priego Jiménez, Maria Quiles Guerola, Elizabeth Redondo Villahoz, Mário Ribeiro Gonçalves, Javier Riera Castellano, Elena Romera Barba, David Ruíz de Angulo, Jesús Salas Martínez, Cristina Sancho Moya, Amparo Valverde Martínez, Ramón Vilallonga Puy, Camilo Zapata Syro, Jorge Zárate Gómez.

The names of the components of the Multimodal Rehabilitation Working Group on Esophagogastric Surgery of the Spanish Multimodal Rehabilitation Group are listed in Addendum 2.

Please cite this article as: Bruna Esteban M, Vorwald P, Ortega Lucea S, Ramírez Rodríguez JM y Grupo de Trabajo de Cirugía Esofagogástrica del Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal (GERM). Rehabilitación multimodal en la cirugía de resección gástrica. Cir Esp. 2017;95:73–82.