The information contained in a good informed consent form (ICF) must be understood by the patients. The aim of this study is to assess and improve the readability of the ICF submitted for accreditation in a tertiary hospital.

MethodsStudy of assessment and improvement of the quality of 132 ICF from 2 departments of a public tertiary hospital, divided into 3 phases: initial assessment, intervention and reassessment. Both length and readability are assessed. Length is measured in words (adequate to 470, excessive over 940), and readability in INFLESZ points (suitable if over 55). The ICF contents initially proposed by departments were adapted by non-health-related trained persons, whose doubts about medical terms were resolved by the authors. To compare results between evaluations, relative improvement (in both length and INFLESZ) and statistical significances were calculated.

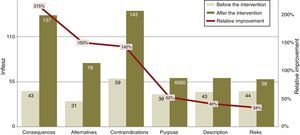

ResultsBaseline data: 78.8% of the ICFs showed a desired length (CI 95% 86.5–71.1) and a mean of 44.1 INFLESZ points (3.8% >55 points, CI 95% 6.0–1.6). After the intervention, INFLESZ raised to 61.9 points (improvement 40.3%, P<.001), all ICF showing >55 points. The resulting ICFs had a longer description of the nature of the procedure (P<.0001) and a shorter description of their consequences, risks (P<.0001) and alternatives (P<.05).

ConclusionsThe introduction of improvement dynamics in the design of ICFs is possible and necessary because it produces more effective and easily readable ICFs.

Contar con documentos de consentimiento informado (DCI) de calidad implica que la información pueda ser comprendida y asimilada por el paciente. El propósito de este estudio es evaluar y mejorar la facilidad de comprensión de los DCI presentados para su acreditación en un hospital de tercer nivel.

MétodosEstudio de evaluación y mejora de la calidad de 132 DCI provenientes de 2 servicios de un hospital público de tercer nivel, estructurado en 3 fases: evaluación inicial, intervención y reevaluación. Se utilizaron 2 criterios: extensión (deseable inferior a 490 palabras) e índice de legibilidad INFLESZ (adecuado si >55 puntos), tanto del DCI completo como de cada uno de sus apartados. Los contenidos propuestos por los servicios fueron adaptados por una persona entrenada no sanitaria, cuyas dudas sobre términos médicos fueron resueltas por los autores. Para comparar los resultados entre evaluaciones se calcularon mejoras relativas en extensión e INFLESZ, y su significación estadística.

ResultadosAntes de la intervención, el 78,8% de los DCI eran de extensión deseable (IC 95%: 86,5-71,1) con un INFLESZ medio de 44,1 puntos (3,8%>55 puntos) (IC 95%: 6,0-1,6). Tras ella, el INFLESZ fue de 61,9 puntos (mejora relativa 40,3%, p<0,001), con el 100%>55. Los DCI resultantes dedican una mayor extensión a describir la naturaleza del procedimiento (p<0,0001) y menor a consecuencias, riesgos (p<0,0001) y alternativas (p<0,05).

ConclusionesIntroducir dinámicas de mejora en el diseño de DCI es posible y necesario, ya que produce DCI de mayor calidad y más fáciles de comprender por los pacientes.

Informed consent has the purpose of ensuring that patients reach a free decision on all procedures that affect their health.1

This communication process is therefore complex, in which the signed consent document (ICD) is a vitally important item as a documental support and tool for the transmission of information.2,3 This is why it is essential to have a high quality ICD, which in practice basically means 3 things: that its content covers the whole spectrum of information that the patient needs to know, that the information it contains is valid (according to the evidence) and that it is written in a way that the patient is able to understand and assimilate. It is therefore advisable to use homogeneous documents or ICD recording, accreditation and updating systems, as several authors point out.4–6

Nevertheless, these measures have not to date been able to guarantee these requisites in a uniform way. Thus while it is easy to structure the information contained in an ICD according to the needs of the patient,4,7,8 and its validity can be checked with the help of scientific societies9,10 or other methods,6,11 the way in which it is written hinders comprehension by many patients. The low legibility of ICD is a widespread problem in Spain12–15 as well as in Europe16–18 and America.19,20 The texts proposed by scientific societies are not immune from this either.21

The purpose of this study is to evaluate and improve the ease of comprehension of the ICD presented for accreditation in a third level hospital.

MethodsThe ‘Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca’ is a public hospital located in the Region of Murcia (Spain). It has used an ICD accreditation system since 2012.6 This study is part of a project to improve the procedures for delivering and signing ICDs in the hospital, and the documents used in the Orthopaedic and Urology Departments were analysed. These use 132 ICD (64 and 68, respectively) divided into 6 sections: description, purpose, consequences, risks, contraindications and alternatives. The analytical criteria of the programme for the Evaluation and Improvement of Care Quality (EMCA) of the Board of Health and Social Policy of the Region of Murcia were used in this study.4

The evaluation and improvement study was undertaken in 3 successive phases: an initial evaluation (to measure the basic quality of the ICD), intervention (with the aim of improving their quality) and re-evaluation (to investigate the improvement attained).

Initial Evaluation132 ICD in the form originally proposed by both departments were received for accreditation and evaluated for ease of comprehension. 2 criteria were used for this: their length and the INFLESZ index. These were applied to the complete ICD as well as to each one of their sections. Measurements of the sections “consequences” and “contraindications” were excluded when the text proposed by the department indicated the absence of any such situation. For example, “this procedure has no consequences”, “it has no contraindications” or similar expressions), given that the hospital Accreditation Committee would replace it with the phrase “There are none” (142.5 INFLESZ points).

- •

Length was measured in words, and it was considered desirable that these documents were shorter than one page. In the ICD format of our hospital, which uses DIN A4 paper and size 12 pp fonts, one page equals 470 words. It was considered to be too long or unadvisable for it to be longer than 2 pages (more than 940 words). It is therefore possible to classify ICD in 3 types according to their length: desirable (up to 470 words), acceptable (471–940 words) and too long (more than 940 words).

- •

INFLESZ is a tool that is used to measure text legibility. It has been adjusted to Spanish reader habits and validated for the evaluation of texts for patients. Texts are more likely to be understood if they score more than 55 points.22 As well as individual scores, the INFLESZ scale sets 5 text complexity bands: “very difficult” (<40.0), “quite difficult” (40.1–55.0), “normal” (55.1–65.0), “quite easy” (65.1–80.0) and “very easy” (>80.0). The Inflesz 1.0 programme is used as the measuring tool, and it is freely available in Internet.23

The contents proposed by the departments were adapted to improve their legibility, with the aim of ensuring that all of their sections attained an INFLESZ score higher than 55 points. An individual who does not work in healthcare was trained to do this, in the type of content that each section of the ICD has to contain as well as how to use the Inflesz 1.0 programme. During this process doubts about the meanings of phrases and medical terms were resolved by the authors, who also revised and approved the final texts after improvement. The aim of all this work was an ICD that is easy to understand in all of its sections and suitably legible (with an INFLESZ score higher than 55) as well as being free of medical or scientific terms that would have created doubts or been hard to understand.

Re-evaluationThe modified 132 ICD were evaluated again using the same measuring tools. To compare the results of the evaluations the relative improvement in average lengths and the INFLESZ score was calculated, as well as the proportion of ICD with a desirable length and an INFLESZ score higher than 55 points.

Statistical AnalysisAnalysis of the results used the Student t-test for quantitative variables (averages) in related samples (averages), and McNemar's test was used for proportions. All differences with a value of P<.05 were considered to be significant.

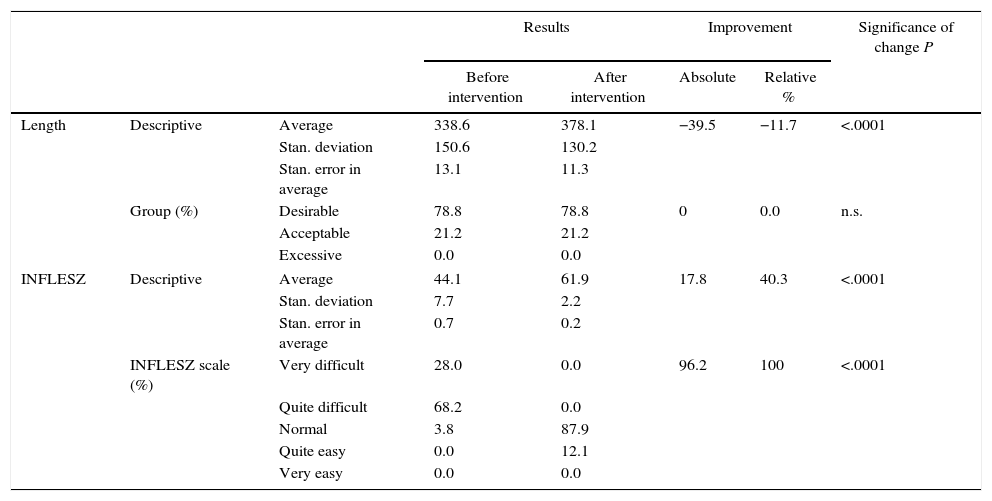

ResultsComplete Consent DocumentsBefore modification the complete consent documents (Table 1) had an average length of 338.6 words, while 78.8% of the ICDs had a desirable length (IC 95%: 86.5–71.1). Their average INFLESZ score was 44.1 points, and the proportion of the ICDs that would probably be understood by an average citizen (more than 55 points) was 3.8% (IC 95%: 6.0–1.6).

Result of the Variables Analysed in the Whole Set of Informed Consent Documents.

| Results | Improvement | Significance of change P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before intervention | After intervention | Absolute | Relative % | ||||

| Length | Descriptive | Average | 338.6 | 378.1 | −39.5 | −11.7 | <.0001 |

| Stan. deviation | 150.6 | 130.2 | |||||

| Stan. error in average | 13.1 | 11.3 | |||||

| Group (%) | Desirable | 78.8 | 78.8 | 0 | 0.0 | n.s. | |

| Acceptable | 21.2 | 21.2 | |||||

| Excessive | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| INFLESZ | Descriptive | Average | 44.1 | 61.9 | 17.8 | 40.3 | <.0001 |

| Stan. deviation | 7.7 | 2.2 | |||||

| Stan. error in average | 0.7 | 0.2 | |||||

| INFLESZ scale (%) | Very difficult | 28.0 | 0.0 | 96.2 | 100 | <.0001 | |

| Quite difficult | 68.2 | 0.0 | |||||

| Normal | 3.8 | 87.9 | |||||

| Quite easy | 0.0 | 12.1 | |||||

| Very easy | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||

Length is measured in number of words.

No., number of documents analysed; n.s., not significant; stan, standard.

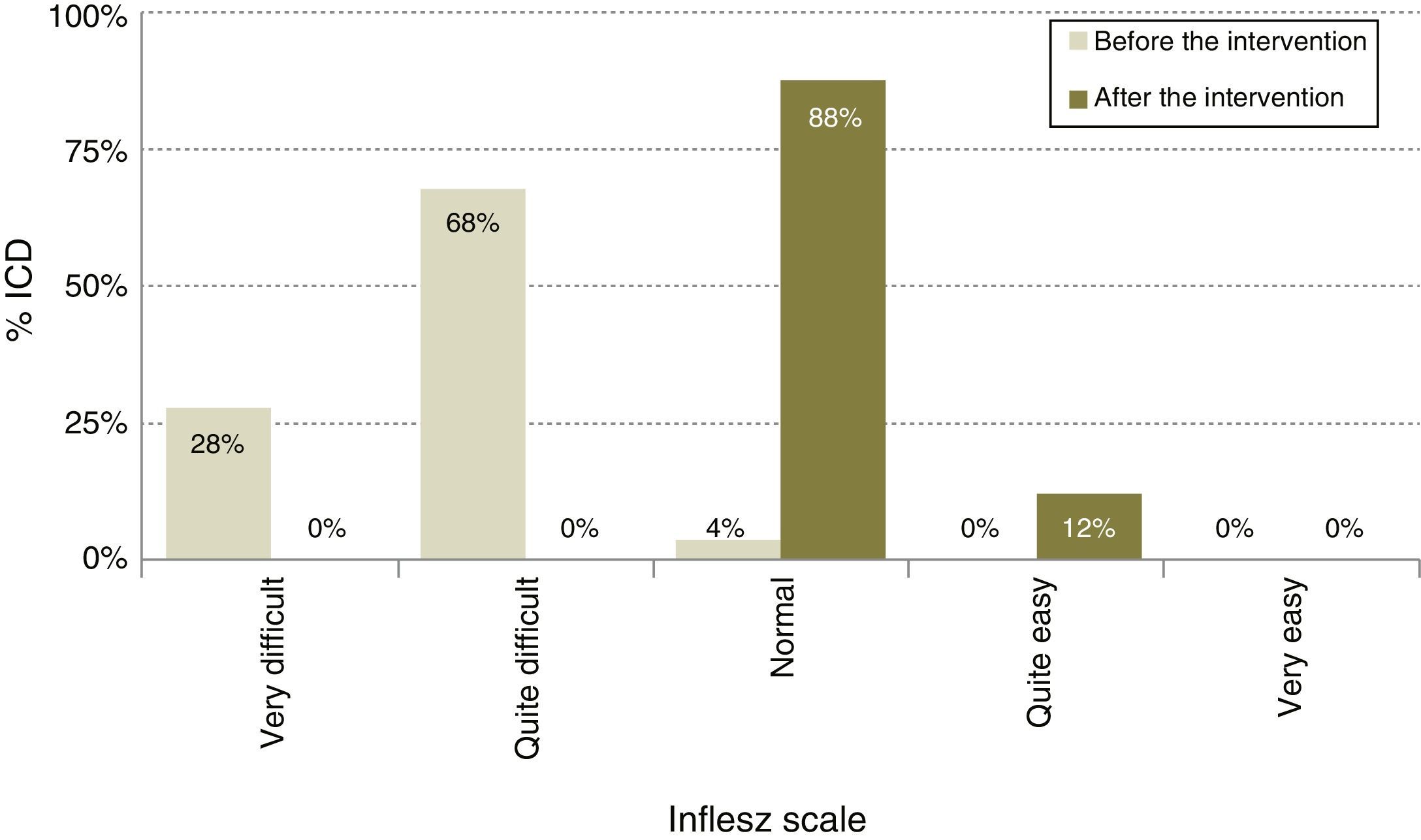

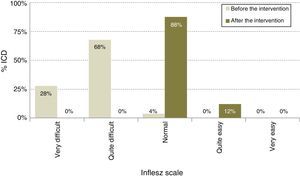

After modification (Table 1), the average length of the ICD rose to 378.1 words, 11.7% longer (P<.0001), although the proportion of ICD with a desirable length did not change and continued at 78.8% (IC 95%: 86.5–71.1). The average INFLESZ score now stood at 61.9 points, and 100% of the ICD scored higher than 55 points. There was therefore an increase of 17.8 points, amounting to a relative improvement of 40.3% (P<.001). The distribution of the ICD on the INFLESZ scale also reflected this improvement (Fig. 1), as they were now all included in the “normal” or “quite easy” categories (P<.0001).

ICD SectionsThe initial evaluation excluded analysis in 108 ICD (81.8%) of the section “consequences”, while in 128 (97.0%) ICD it excluded “contraindications” as they fulfilled the exclusion criterion, so that it was decided not to include these results in comparative tests. The original 132 ICD were included for all the other sections.

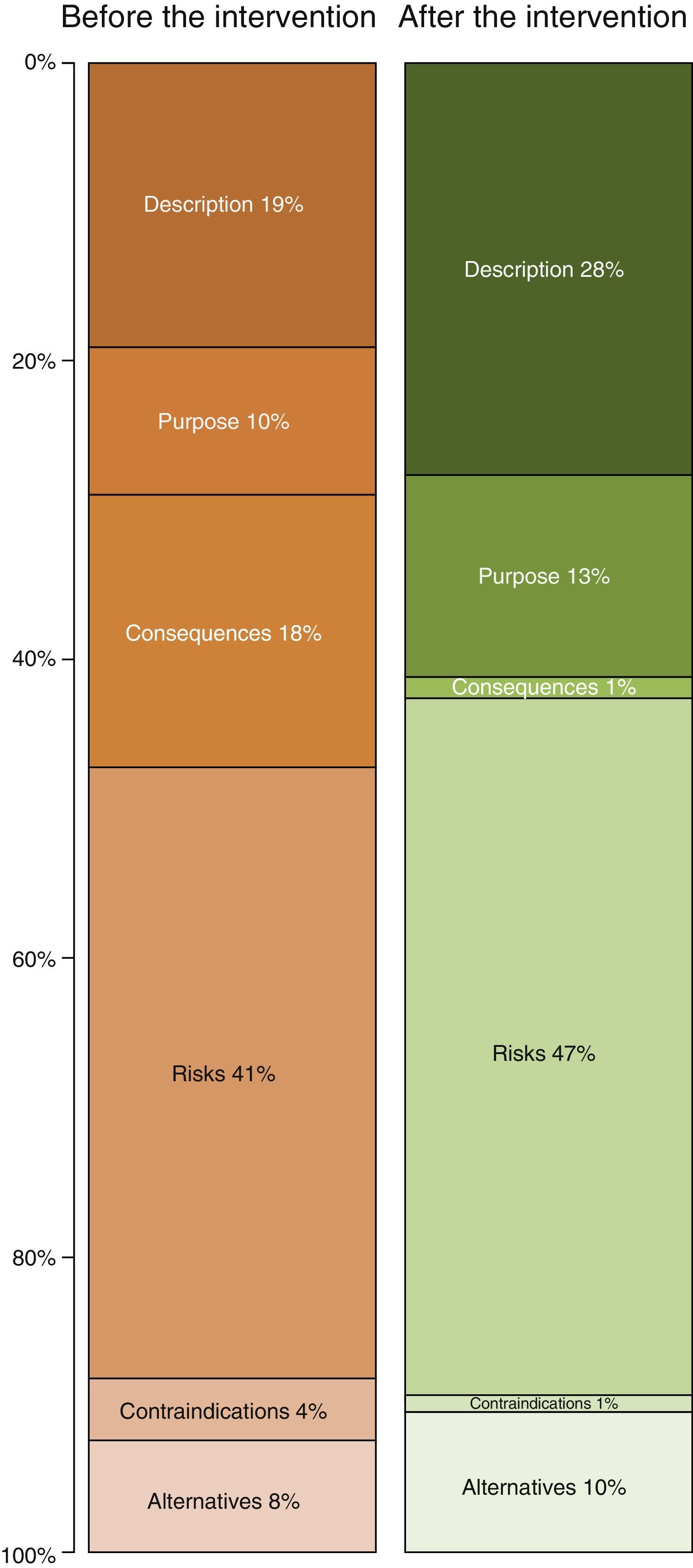

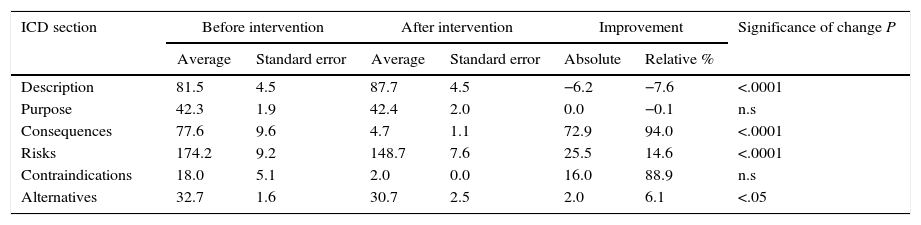

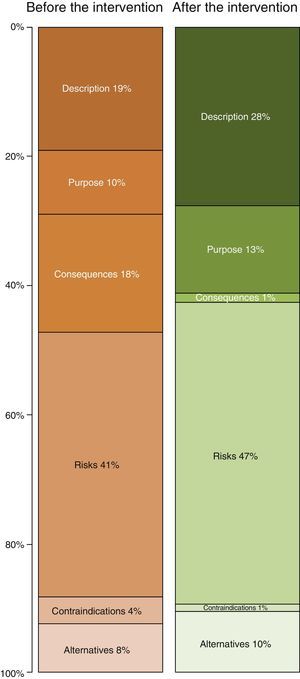

Table 2 shows the length of the sections in the ICD. The longest ones before improvement were the descriptions of risks (41% of the total) and descriptions of the procedure (19%). After the improvement the longest sections were still those on “risks” and “the procedure”, although the degree to which each of these contributed to the total length of the ICD varied (Fig. 2). Thus the resulting ICD used more words in describing the procedure (P<0.0001) and fewer for consequences and risks (P<.0001) as well as alternatives (P<.05).

Length in Number of Words of the Sections in the Informed Consent Documents.

| ICD section | Before intervention | After intervention | Improvement | Significance of change P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard error | Average | Standard error | Absolute | Relative % | ||

| Description | 81.5 | 4.5 | 87.7 | 4.5 | −6.2 | −7.6 | <.0001 |

| Purpose | 42.3 | 1.9 | 42.4 | 2.0 | 0.0 | −0.1 | n.s |

| Consequences | 77.6 | 9.6 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 72.9 | 94.0 | <.0001 |

| Risks | 174.2 | 9.2 | 148.7 | 7.6 | 25.5 | 14.6 | <.0001 |

| Contraindications | 18.0 | 5.1 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 16.0 | 88.9 | n.s |

| Alternatives | 32.7 | 1.6 | 30.7 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 6.1 | <.05 |

n.s.: not significant.

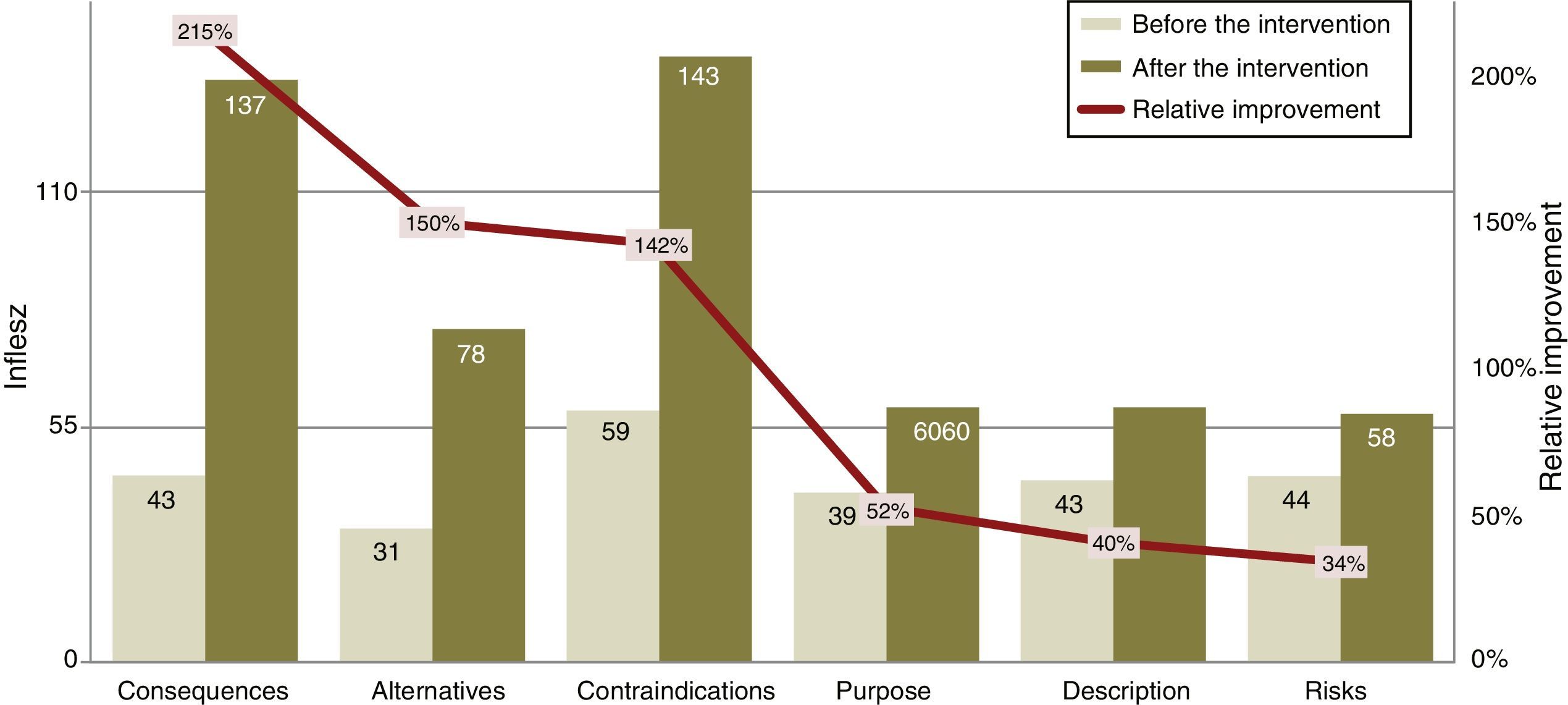

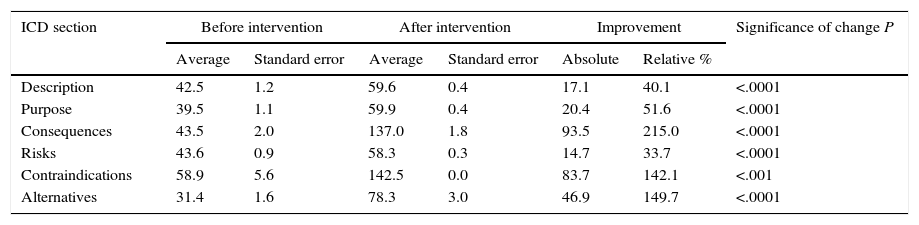

The INFLESZ scores of the ICD sections (Table 3) varied at first from 31.4 points for the section on alternatives up to 43.6 points for the description of risks. After the improvement the risks section scored the lowest (58.3) while the contraindications section scored the highest (142.5). The improvements detected (Fig. 3) applied to all of the sections and were highly significant.

The Legibility in INFLESZ Points of the Section in the Informed Consent Documents.

| ICD section | Before intervention | After intervention | Improvement | Significance of change P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard error | Average | Standard error | Absolute | Relative % | ||

| Description | 42.5 | 1.2 | 59.6 | 0.4 | 17.1 | 40.1 | <.0001 |

| Purpose | 39.5 | 1.1 | 59.9 | 0.4 | 20.4 | 51.6 | <.0001 |

| Consequences | 43.5 | 2.0 | 137.0 | 1.8 | 93.5 | 215.0 | <.0001 |

| Risks | 43.6 | 0.9 | 58.3 | 0.3 | 14.7 | 33.7 | <.0001 |

| Contraindications | 58.9 | 5.6 | 142.5 | 0.0 | 83.7 | 142.1 | <.001 |

| Alternatives | 31.4 | 1.6 | 78.3 | 3.0 | 46.9 | 149.7 | <.0001 |

It is a well-known fact that patients usually have problems in understanding the contents of the ICD they are offered12,24 and that making them more legible is one of the most effective ways of improving their comprehension.25 Although they are restricted to the ICD of 2 specialities in a single hospital, the results of this study show that it is both possible and necessary to improve them: this gives rise to higher quality ICDs in terms of their length and legibility, with appropriate INFLESZ scores showing that normal citizens can understand them,22 without the need to make them longer (another factor which we know hinders reading them).12,20 This therefore adds value to the process of information and consent for which they are designed.

No other studies were found in which a complete cycle of hospital ICD legibility evaluation and improvement had been carried out prior to their use for specific patients. This prevents comparison of the resulting improvements with those of other studies.

Although the design of this study does not permit analysis of the effect of the intervention, this goes beyond the creation of texts with a good INFLESZ score. This is calculated by a formula which evaluates the degree to which a text is difficult according to the length of its words and phrases, although it does not take the language used into account. Although the individual who adapted the ICD was properly trained for this, they do not work in healthcare. The aim of this was to add the patient's viewpoint to the process of creating the ICDs, as definitively it is they who have to understand them. This avoids the use of “medical jargon” in the ICDs even though they have a good INFLESZ score, as this is another major hindrance for comprehension.26 The major changes in the lengths of different sections of the ICD, which doubles in the case of the description of the procedure (what it consists of), and falls in the case of the consequences (safe effects) and contraindications (Fig. 3) may be explained by the fact that patients need information about what will be done, while doctors seek legal support too, in case they need it.16,27,28

Actively involving patients and analysing the impact of this on the structure of ICDs should be general practice: although this initiative is not unique, more such schemes would be desirable: improving and perfecting the rest of the consent process apart from the document itself is another question.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Picazo Ferrer JJ, Tomás Garcia N. Evaluación y mejora de la comprensión de los documentos de consentimiento informado. Cir Esp. 2016;94:221–226.