Surgery is the accepted treatment for infected acute pancreatitis, although mortality remains high. As an alternative, a staged management has been proposed to improve results. Initial percutaneous drainage could allow surgery to be postponed, and improve postoperative results. Few centers in Spain have published their results of surgery for acute pancreatitis.

ObjectiveTo review the results obtained after surgical treatment of acute pancreatitis during a period of 12 years, focusing on postoperative mortality.

Materials and methodsWe have reviewed the experience in the surgical treatment of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) at Bellvitge University Hospital from 1999 to 2011. To analyze the results, 2 periods were considered, before and after 2005. A descriptive and analytical study of risk factors for postoperative mortality was performed.

ResultsA total of 143 patients were operated on for SAP, and necrosectomy or debridement of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis was performed, or exploratory laparotomy in cases of massive intestinal ischemia. Postoperative mortality was 25%. Risk factors were advanced age (over 65 years), the presence of organ failure, sterility of the intraoperative simple, and early surgery (<7 days). The only risk factor for mortality in the multivariant analysis was the time from the start of symptoms to surgery of <7 days; furthermore, 50% of these patients presented infection in one of the intraoperative cultures.

ConclusionsPancreatic infection can appear at any moment in the evolution of the disease, even in early stages. Surgery for SAP has a high mortality rate, and its delay is a factor to be considered in order to improve results.

La cirugía es el tratamiento aceptado en la pancreatitis aguda infectada, aunque la mortalidad sigue siendo elevada. Como alternativa, el manejo en etapas se ha propuesto como alternativa para mejorar los resultados. El drenaje percutáneo inicial permitiría demorar la cirugía, y mejorar los resultados postoperatorios. Pocos centros a nivel nacional han publicado sus resultados tras la cirugía por pancreatitis aguda.

ObjetivoRevisar los resultados obtenidos tras el tratamiento quirúrgico de pancreatitis aguda durante un período de 12 años, con especial interés en la mortalidad postoperatoria.

Material y métodosHemos recogido la experiencia en el tratamiento quirúrgico de la pancreatitis aguda grave (PAG) en el Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge desde 1999 hasta 2011. Para analizar los resultados, consideramos 2 períodos de estudio, anterior y posterior a 2005. Realizamos un estudio descriptivo y un análisis de factores de riesgo de mortalidad postoperatoria.

ResultadosSe ha intervenido a 143 pacientes por PAG, realizándose necrosectomía o desbridamiento de necrosis pancreática o peripancreática, o laparotomía exploradora en caso de hallar isquemia intestinal masiva. La mortalidad postoperatoria ha sido del 25%. Los factores de riesgo fueron la edad avanzada (superior a 65 años), la presencia de fallo orgánico, la esterilidad de la muestra intraoperatoria obtenida y la cirugía precoz (< 7 días). El único factor de riesgo de mortalidad en el estudio multivariante fue el tiempo desde el inicio de la clínica a la cirugía menor o igual a 7 días. Asimismo, demostramos que un 50% de estos pacientes presentaron infección en algún cultivo intraoperatorio.

ConclusionesLa infección pancreática puede aparecer en cualquier momento de la evolución de la enfermedad, incluso en fases tempranas. La cirugía en PAG comporta una elevada mortalidad, y la demora de la misma es un factor a tener en cuenta para mejorar los resultados.

Treatment of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) has changed significantly in recent years. Pancreatic resection was advocated during the 70s and 80s, despite its very high postoperative mortality rates.1–4 It was assumed that pancreas resection could help minimize the triggered systemic damage. However, later it was shown that the triggered inflammatory cascade did not stop after pancreatic resection. Several developments contributed to better plan acute pancreatitis treatment. These included computed tomography,5,6 emergence of broad-spectrum antibiotics and improved intensive care procedures.7,8 Finally, the introduction of open necrosectomy with its various forms, contributed to improve survival in this disease.9–13 Then, with the celebration of the Atlanta Conference in 1992,14 the basis for managing patients with acute pancreatitis were set. However, in subsequent years, differences in treating necrosis persisted. Thus, while some authors still advocated surgery for patients with sterile necrosis15,16 or early surgery,17,18 others advocated delaying surgery19,20 or selecting only infected patients.21 The appearance of clinical guidelines from various international associations22–24 helped clinicians standardize how to treat acute pancreatitis.

According to current clinical guidelines, at present, patients with infected pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis and severe sepsis continue to undergo surgery.22,24,25 Debridement of pancreatic or peripancreatic necrotic tissue is the purpose of surgery. Recently, it has been shown that treatment during infected necrosis phases comprises a lower rate of major complications, with similar mortality and hospital stay than the classical approach by laparotomy.26,27 Endoscopic or percutaneous initial treatment and subsequent surgery is proposed according to progression, a fact that is reflected in the most recent clinical guidelines.28–31 However, there are unanswered questions about infected acute pancreatitis treatment: Should we operate in cases with rapid deterioration? Is necrosis infection possible during the first week of admission? And if so, should we operate on patients with infected pancreatic necrosis during the first week? This study aims to define the risk factors for death after acute pancreatitis surgery, and analyze developments in treating this disease at our center over a period of 12 years.

Materials and MethodsStudy PopulationBetween 1999 and 2011 we have treated 1419 pancreatitis cases in 1046 patients admitted to the Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery Unit at the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge [University Hospital of Bellvitge] in L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona. Our center is the highly complex referral hospital for a population of 2 million. All cases were systematically entered in a database, in a prospective manner. According to criteria of the Conference of Atlanta, 495 cases were classified as SAP,14 and 143 of them underwent surgery, all the latter comprising the study population.

Variables Analyzed and DefinitionsA total of 265 variables were analyzed including patient demographics, etiology, case history, intraoperative and postoperative details of each patient. The database has been completed in a prospective manner.32,33 We defined organ failure according to criteria defined by Büchler on respiratory failure, renal failure, shock, gastrointestinal bleeding, disseminated intravascular coagulation and hypocalcaemia.13 We defined SAP as that related to organ failure or local complications, according to 1992 Atlanta criteria.14 Early surgery was that which took place on day 7 from onset of symptoms or before, and late surgery was performed afterwards. Intraoperative tissue culture was the culture result from pancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic fat, as discussed in the previous study.34

Postoperative TreatmentThe monitoring and treatment of acute pancreatitis patients has been carried out entirely by the Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery Unit in our center. Patients with SAP were treated with intravenous fluid replacement, nasogastric aspiration if vomiting, and total parenteral nutrition without antibiotic prophylaxis, following the results of previously published studies.35 For respiratory failure or hemodynamic instability events, patients were transferred to the intensive care unit, for monitoring and medical treatment. Computerized tomography (CT) was scheduled within 72h after admission; it was performed earlier in patients with unsure diagnosis. Patients with suspected pancreatic infection underwent percutaneous CT-guided aspiration of pancreatic necrosis or peripancreatic fat or collections for microbiological analysis (Gram stain and culture).

The surgical team dedicated to the disease prescribed surgery when Gram or culture showed infection, if blood cultures were positive, presence of gas on CT or sudden worsening of the patient. During the early years of the study, many patients without infection underwent surgery if they had persistent and irreversible organ failure.

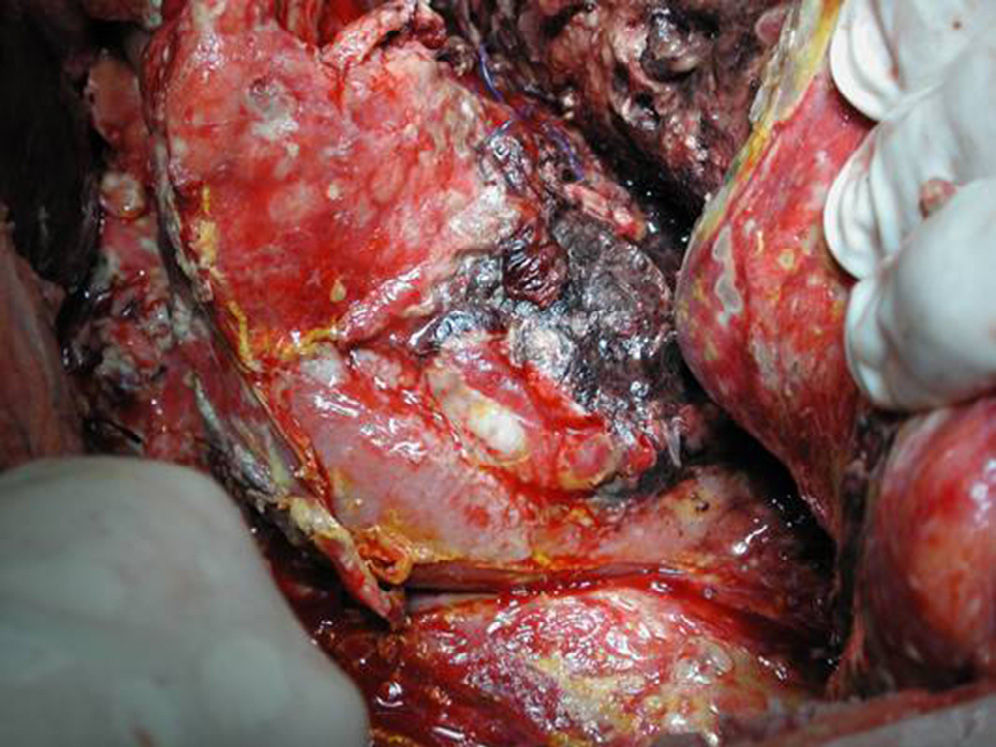

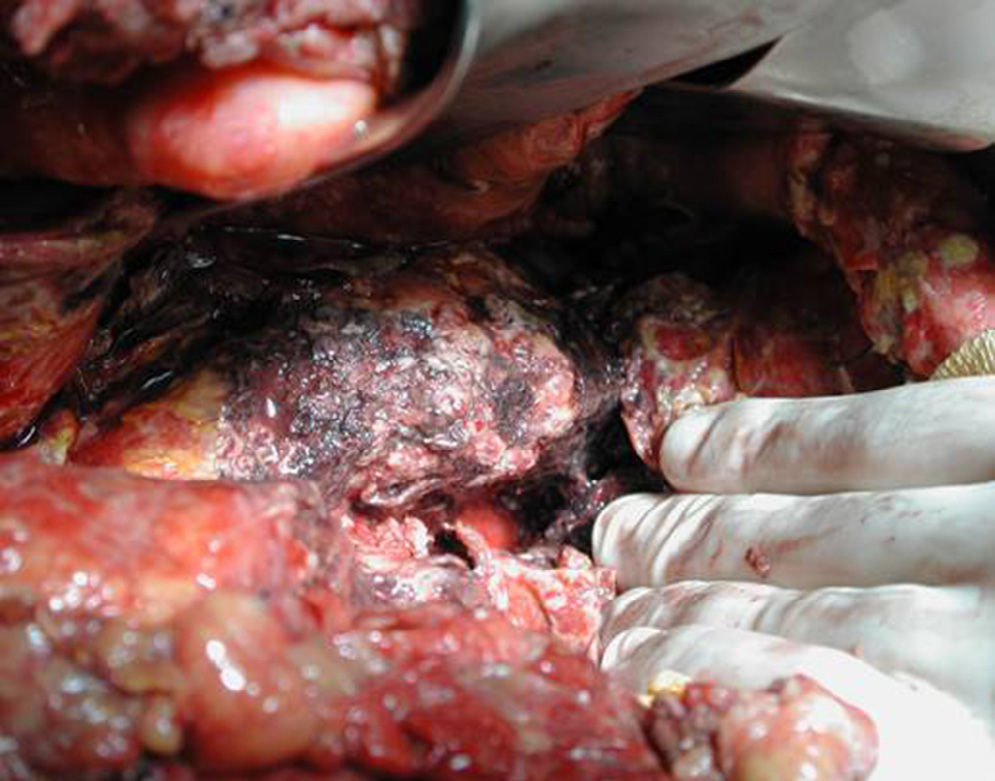

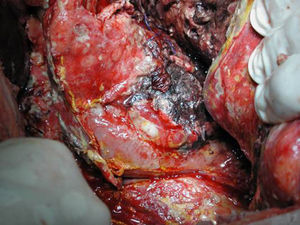

Surgical ProcedureSurgery was planned based on abdominal CT findings, performing a surgical necrosectomy,10 preferably with cholecystectomy (Figs. 1 and 2). Surgery was initiated with bilateral subcostal laparotomy, including pancreatic cell access through the gastrocolic omentum. In cases of cephalic involvement, a Kocher maneuver was performed to debride the cephalic necrosis. The procedure ended with drain placement in the pancreatic body and in the cephalic area. A continuous lavage system was put in place with high rate saline (24l [liters] of physiological serum daily) during the first days, and progressively decreased depending on the patient's clinical course. Intraoperative cultures were obtained at various times in surgery.36 Intra-abdominal fluid sample was taken after laparotomy, and before mobilization. After opening the pancreatic cell, peripancreatic fat and pancreatic necrosis samples were obtained. In the event cholecystectomy was performed, bile culture sample was sent. After surgery, the patient was transferred to intensive care, with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Statistical AnalysisAn initial descriptive statistical analysis was performed. Then, a comparative analysis was performed between qualitative variables according to Chi-square or Fisher test, and quantitative variables according to Mann–Whitney U test. Finally, a binary logistic regression model was designed; the dependent variable was postoperative mortality. SPSS 12.0® statistics software was used, and the statistically significant value take into account was P<.05 in all cases. We created a variable, according to surgery time, considering period 1 as that prior to June 2005, and period 2 after July 2005.

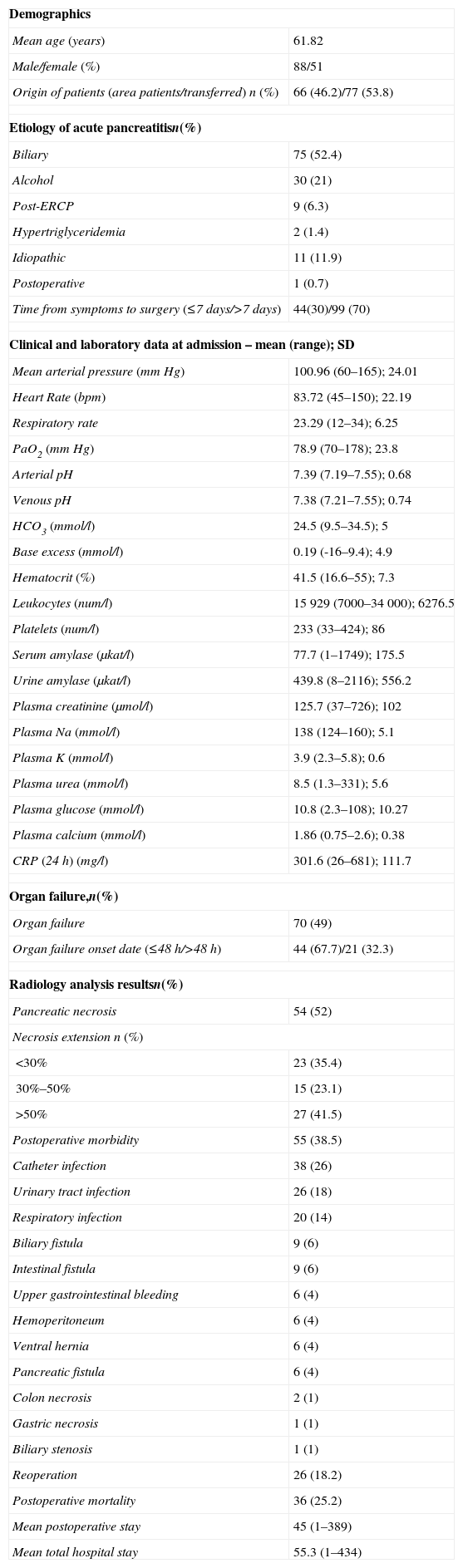

ResultsDescriptive StudyDuring the study period, 143 patients underwent acute pancreatitis surgery in our hospital. A total of 90 patients underwent surgery in period 1 (64%) and 53 (36%) in period 2. Most were men (63%), the most common cause was acute gallstone pancreatitis (52%) (Table 1). With respect to preoperative treatment, 77 patients (54%) were referred from other nearby hospitals, and 49 patients (34%) had received a prophylactic antibiotic. We found that 20% had an episode of acute pancreatitis previously. Most relevant medical history were: ischemic heart disease (13/9%), severe bronchial disease (10/7%), heart failure (6/4%) and liver cirrhosis (3/2%).

Descriptive Analysis of Patients Undergoing Surgery for Severe Acute Pancreatitis.

| Demographics | |

| Mean age (years) | 61.82 |

| Male/female (%) | 88/51 |

| Origin of patients (area patients/transferred) n (%) | 66 (46.2)/77 (53.8) |

| Etiology of acute pancreatitisn(%) | |

| Biliary | 75 (52.4) |

| Alcohol | 30 (21) |

| Post-ERCP | 9 (6.3) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 2 (1.4) |

| Idiopathic | 11 (11.9) |

| Postoperative | 1 (0.7) |

| Time from symptoms to surgery (≤7 days/>7 days) | 44(30)/99 (70) |

| Clinical and laboratory data at admission – mean (range); SD | |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 100.96 (60–165); 24.01 |

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 83.72 (45–150); 22.19 |

| Respiratory rate | 23.29 (12–34); 6.25 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 78.9 (70–178); 23.8 |

| Arterial pH | 7.39 (7.19–7.55); 0.68 |

| Venous pH | 7.38 (7.21–7.55); 0.74 |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 24.5 (9.5–34.5); 5 |

| Base excess (mmol/l) | 0.19 (-16–9.4); 4.9 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.5 (16.6–55); 7.3 |

| Leukocytes (num/l) | 15929 (7000–34000); 6276.5 |

| Platelets (num/l) | 233 (33–424); 86 |

| Serum amylase (μkat/l) | 77.7 (1–1749); 175.5 |

| Urine amylase (μkat/l) | 439.8 (8–2116); 556.2 |

| Plasma creatinine (μmol/l) | 125.7 (37–726); 102 |

| Plasma Na (mmol/l) | 138 (124–160); 5.1 |

| Plasma K (mmol/l) | 3.9 (2.3–5.8); 0.6 |

| Plasma urea (mmol/l) | 8.5 (1.3–331); 5.6 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 10.8 (2.3–108); 10.27 |

| Plasma calcium (mmol/l) | 1.86 (0.75–2.6); 0.38 |

| CRP (24h) (mg/l) | 301.6 (26–681); 111.7 |

| Organ failure,n(%) | |

| Organ failure | 70 (49) |

| Organ failure onset date (≤48h/>48h) | 44 (67.7)/21 (32.3) |

| Radiology analysis resultsn(%) | |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 54 (52) |

| Necrosis extension n (%) | |

| <30% | 23 (35.4) |

| 30%–50% | 15 (23.1) |

| >50% | 27 (41.5) |

| Postoperative morbidity | 55 (38.5) |

| Catheter infection | 38 (26) |

| Urinary tract infection | 26 (18) |

| Respiratory infection | 20 (14) |

| Biliary fistula | 9 (6) |

| Intestinal fistula | 9 (6) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 6 (4) |

| Hemoperitoneum | 6 (4) |

| Ventral hernia | 6 (4) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 6 (4) |

| Colon necrosis | 2 (1) |

| Gastric necrosis | 1 (1) |

| Biliary stenosis | 1 (1) |

| Reoperation | 26 (18.2) |

| Postoperative mortality | 36 (25.2) |

| Mean postoperative stay | 45 (1–389) |

| Mean total hospital stay | 55.3 (1–434) |

Source: H.U. Bellvitge, 1999–2011.

n=143.

On admission, analytical findings revealed an average leukocyte count of 15928, mean creatinine 125 (μmol/l), and mean CRP 301 (mg/l). Regarding progression at surgery time, 70 (50%) patients had experienced some type of parenchyma failure. Specifically, 44% of patients had respiratory failure, 20% and 29% shock renal failure. In total, 30 patients (20%) experienced failure of 3 organs. Mean time for organ failure onset was day 4 (1–22), appearing during the first 48h in 30% (Table 1). CT was performed in all studied patients. CT-guided fine needle puncture was performed in 103 patients (72%). A total of 34 (33%) patients underwent surgery, although they were Gram negative.

As for pre-surgical treatment, we have recorded placement of percutaneous drainage since 2007 in 52 patients; where 15 of them finally underwent surgery. Furthermore, collection or necrosectomy debridement was conducted endoscopically in 18, of which 5 cases required surgery. Mean time from onset of symptoms to surgery was 15.6 days (1–89), with less than 7 days in 44 cases (31%), and less than 12 days in 69 (49%). Surgery consisted in necrosectomy (75%) or debridement of infected encapsulated necrosis or pseudocyst (25%); cholecystectomy was performed simultaneously in 97 (68%). A total of 6 patients showed massive intestinal ischemia during laparotomy. In reference to microbiology collected during surgery, tissue culture (pancreatic necrosis or peripancreatic fat) was recorded in 78 patients. A total of 59 (75%) of them showed infection, and the culture was sterile in 19 (25%).

Postoperative Morbidity and MortalityMean postoperative hospital stay was 45 days (1–389). In 55 (38%) some type of postoperative complication was recorded directly related to surgery, and 26 (18%) patients were reoperated on. The most frequent complications were: catheter infection (26%), urinary tract infection (18%), and respiratory infection (14%). Digestive complications included biliary fistula (9 patients), intestinal fistula (9 patients), and pancreatic fistula (6 patients) (Table 1). Postoperative mortality was 25% (36 patients). We divided the series based on postoperative progression, and observed that patients who died were older (67 compared to 60 years; P=.01), had poorer preoperative renal function (creatinine 161μmol/l compared to 113μmol/l; P=.04), and greater preoperative hematocrit (44 compared to 40%; P=.02). The time between onset of symptoms and surgery was shorter in the group of patients who died (11 compared to 17 days, P=.01).

In the bivariate study, several factors were related to increased postoperative mortality: advanced age, organ failure, precocity in the onset of organ failure (<48h), sterility of intraoperative cultures, and a short time from onset of symptoms to surgery (Table 2) time. However, we found that administering prophylactic antibiotics did not influence mortality. Similarly, those patients who required debridement multiple times, did not experience higher mortality rates than those undergoing surgery only once. Finally, mortality in patients undergoing surgery without previous percutaneous drainage (27%) was greater than mortality in patients undergoing surgery after receiving percutaneous drainage (6.7%); this was not a statistically significant difference (P=.08).

Factors Related to Mortality After Surgery for Severe Acute Pancreatitis.

| Mortality (%) | Pa | |

| Age (<65 years/>65 years) | 16 vs 35 | .008 |

| Sex (male/female) | 19 vs 33 | .06 |

| Organ failure (yes/no) | 36 vs 15 | .04 |

| Date of organ failure onset (during the first 48h/after the first 48h) | 47 vs 14 | .009 |

| Kidney failure (yes/no) | 40 vs 19 | .007 |

| Shock (yes/no) | 45 vs 22 | .006 |

| Respiratory failure (yes/no) | 35 vs 17 | .01 |

| Hypocalcaemia (yes/no) | 38 vs 21 | .04 |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (yes/no) | 67 vs 23 | .01 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation (yes/no) | 2.8 vs 1.9 | ns |

| Growing intraoperative pancreatic necrosis (positive/negative) | 15 vs 56 | .001 |

| Peripancreatic fat culture (positive/negative) | 6 vs 30 | .002 |

| Growing intraoperative pancreatic and peripancreatic fat necrosis (positive/negative) | 13 vs 47 | .002 |

| Surgical reoperation (yes/no) | 19 vs 26 | ns |

| Pancreatic parenchyma necrosis in CT (yes/no) | 23 vs 27 | ns |

| Necrosis extension on CT (<50/>50%) | 24 vs 26 | ns |

| Time from onset of symptoms to surgery (<7 days/>7 days) | 43 vs 17 | .001 |

| Surgery period (1999–2005/2005–2011) | 29 vs 19 | ns |

| Preoperative percutaneous drainage placement (yes/no) | 6.7 vs 27 | ns |

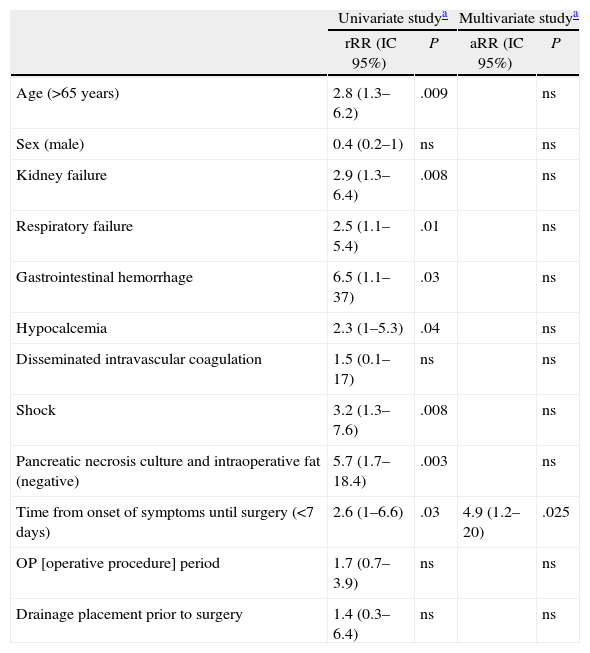

The univariate analysis yielded the following mortality risk factors: over 65 years of age, negative pancreatic necrosis and intraoperative fat culture, period from onset of symptoms to surgery shorter than 7 days, and having organ failure prior to surgery. When analyzing organ failure, we found that mortality was greater with renal failure, respiratory failure, shock, gastrointestinal bleeding or hypocalcaemia. Multivariate analysis showed that only a period from onset of symptoms to surgery equal or less than 7 days was a risk factor for mortality after surgery. Organ failure and sterility of operative cultures, despite being relevant, stopped being the cause for mortality risk in the multivariate analysis (Table 3). Finally, we analyze the case series according to the time of surgery, from the start of symptoms. We found that patients undergoing surgery during the first week experienced organ failure in 48% of cases, similar to those undergoing surgery at a later time. However, 80% of those who underwent early surgery experienced organ failure during the first 2 days after admission. Infection was demonstrated in 50% of those operated early, and 84% of those operated starting on day 8 from onset of symptoms.

Mortality Risk Factors After Severe Acute Pancreatitis Surgery.

| Univariate studya | Multivariate studya | |||

| rRR (IC 95%) | P | aRR (IC 95%) | P | |

| Age (>65 years) | 2.8 (1.3–6.2) | .009 | ns | |

| Sex (male) | 0.4 (0.2–1) | ns | ns | |

| Kidney failure | 2.9 (1.3–6.4) | .008 | ns | |

| Respiratory failure | 2.5 (1.1–5.4) | .01 | ns | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 6.5 (1.1–37) | .03 | ns | |

| Hypocalcemia | 2.3 (1–5.3) | .04 | ns | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 1.5 (0.1–17) | ns | ns | |

| Shock | 3.2 (1.3–7.6) | .008 | ns | |

| Pancreatic necrosis culture and intraoperative fat (negative) | 5.7 (1.7–18.4) | .003 | ns | |

| Time from onset of symptoms until surgery (<7 days) | 2.6 (1–6.6) | .03 | 4.9 (1.2–20) | .025 |

| OP [operative procedure] period | 1.7 (0.7–3.9) | ns | ns | |

| Drainage placement prior to surgery | 1.4 (0.3–6.4) | ns | ns | |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; aRR, absolute relative risk; rRR, raw relative risk.

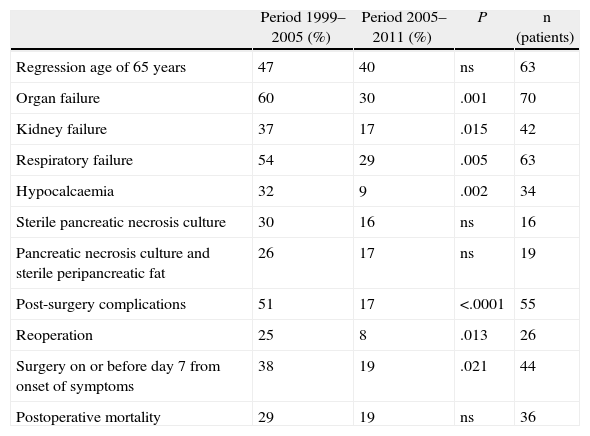

We compared the 90 patients operated on during the first study period to 52 operated in the second (Table 4). Patients operated on during the first study period were treated in a more precarious situation, as 60% had organ failure, compared to 30% in the second period (P=.001). Moreover, during the first study period patients were operated on much earlier: the time from onset of symptoms to surgery was shorter than or equal to 7 days in 38% of patients in the first study period, compared to 19% of patients in the second study period (P=.021). The analysis showed higher mortality during the first study period compared to the second period, although this was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Results According to Study Period.

| Period 1999–2005 (%) | Period 2005–2011 (%) | P | n (patients) | |

| Regression age of 65 years | 47 | 40 | ns | 63 |

| Organ failure | 60 | 30 | .001 | 70 |

| Kidney failure | 37 | 17 | .015 | 42 |

| Respiratory failure | 54 | 29 | .005 | 63 |

| Hypocalcaemia | 32 | 9 | .002 | 34 |

| Sterile pancreatic necrosis culture | 30 | 16 | ns | 16 |

| Pancreatic necrosis culture and sterile peripancreatic fat | 26 | 17 | ns | 19 |

| Post-surgery complications | 51 | 17 | <.0001 | 55 |

| Reoperation | 25 | 8 | .013 | 26 |

| Surgery on or before day 7 from onset of symptoms | 38 | 19 | .021 | 44 |

| Postoperative mortality | 29 | 19 | ns | 36 |

So far, there have been few studies nationwide showing their results in SAP surgery.37–40 The aim of the study submitted was first to review the factors having greater postoperative mortality, and second to analyze SAP treatment progression in our center. Treating these patients requires a multidisciplinary team in order to obtain good results, as reflected in the Spanish Pancreatic Club guide.29 In our center, the surgery department is in charge of treating these patients from their first day of admission. This has greatly involved our group in the disease.32–35 As mentioned above, patients suspected of pancreatic infection and sepsis symptoms undergo CT puncture systematically. Surgery is considered when Gram or percutaneous culture performed is positive, regardless of the progression stage from admission.22,24 In our experience, 75% of patients with intraoperative submitted sample (59/78) were infected, while 25% of pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue samples were sterile (19/78). Puncture to diagnose infection in cases with pancreatic necrosis related to sepsis symptoms or organ failure was performed regardless of pancreatitis progression stage. Thus, half of the patients operated on during the first week had pancreatic or peripancreatic infection (10/20). During the early years of our case series and based on practice at the time, surgery was prescribed in sterile pancreatitis cases with poor outcome, whether infection was confirmed or otherwise. Specifically, 26% of patients in the first period and 17% in the second period were operated on due to sterile pancreatitis, with no statistically significant differences. This practice was abandoned after scientific evidence appeared against sterile surgery for pancreatitis.41

Moreover, when comparing the 2 surgical periods, a greater percentage of organ failure is detected at the time of surgery, and the greatest precocity when surgery is performed in the first period. It is possible that the experience gained in treating these patients over the years has contributed to decreased postoperative morbidity (51 compared to 17%; P<.0001), which is statistically significant. Similarly, we show a decrease in reoperation rates in the second period (25 compared to 8%; P=.013). During the second period, we detected a decrease in postoperative mortality (29 compared to 19%), although this difference was not statistically significant. Patient selection and more targeted treatment in the context of a multidisciplinary approach have contributed to better results.

Postoperative Mortality PredictorsRecent studies have defined advanced age, organ failure, early surgery or percentage of pancreatic necrosis as risk factors for mortality after surgery.42–45 As mentioned above, the patient's systemic condition at the time of surgery plays a fundamental role in disease progression, since pancreatitis infection and sterility are situations representing a proven risk of death for these patients.42 Various studies show that patients with operated sterile necrosis had high morbidity and mortality rates.41 In a previously published case series,34 mortality after surgery for sterile pancreatitis was 40%, compared to 20% for infected necrosis cases. In the same vein, the submitted univariate analysis confirms that surgery must be avoided in sterile necrosis, because it is related to higher mortality. As known, pancreatic necrosis infection may be confirmed only by guided preoperative percutaneous puncture.46 Based on current guidelines,28,47 in our center, patients with suspected pancreatic infection are analyzed by guided puncture. However, some authors found no benefit in performing puncture in the event of glandular necrosis,48,49 although it is a test with 88% sensitivity and 90% specificity.50

Surgical Indication and Progression of the ProcedureThe benefits of surgery are removal of infected necrotic tissue and resulting control of sepsis. However, the time for surgery must be analyzed in detail. Although pancreatic infection during the first week has been confirmed and therefore, theoretical basis exists for debridement, at that time pancreatic necrosis is not well defined and the patient's state is usually very labile, therefore, in this period no debridement is optimal and mortality high.36 A randomized study comparing early surgery vs delayed surgery19 showed that mortality was lower in patients in whom surgery was delayed. Several subsequent studies support these results,20,51,52 comparing mortality after surgery before day 1453,54 or day 2855 since admission. Previous results from our group34 are in line with this, showing better results if we wait 12 days from onset of symptoms. Furthermore, the Dutch multicenter group published mortality reaching 78% after early surgery.56 In our experience, patients operated on during the first week from onset of symptoms die in 43% of cases, and surgery time is the most influential variable in the analysis of postoperative mortality.

At the other end of the spectrum, i.e., treatment without drainage or pancreatic necrosis surgery, results are not promising. Van Santvoort's study56 shows in detail the flow of patients with pancreatic necrosis. Mortality among 63 patients with pancreatic necrosis and organ failure who were treated conservatively (no drainage or surgery) was 37%. Thus, nihilistic treatment in some groups also remains in question.

An intermediate approach between early surgery and conservative treatment without drainage or surgery, would be treatment in stages or “step-up approach”. In a randomized study, the Dutch group showed less major complications after the step-up approach, despite experiencing similar mortality and hospital stay in the surgery group.26,27 Despite its failure to show statistically significant differences regarding mortality, most groups have adopted this approach as it provides patients the advantage of delaying surgery. Moreover, by carefully analyzing the study we found that all included patients underwent surgery at day 12 from onset of symptoms, therefore, we do not know how this viewpoint would apply for the early days of admission. In an extensive update, van Baal57 analyses percutaneous drainage treatment results. Few groups use percutaneous drainage treatment during the early days after onset of symptoms.58–61 In another area, when analyzing the reasons for failure of the step-up approach, the Chandigarh group from India62 showed that renal failure, high APACHE II score and multibacterial infection were the factors posing higher risk of conversion to surgery. Probably in the future we may be able to foretell in which patients the step-up approach will fail. Thus, at present, treating infected SAP patients with organ failure during the first week after onset of symptoms, remains controversial.

ConclusionsAcute pancreatitis surgery implies a high mortality rate, which is increased if carried out during the first week from onset of symptoms. The complexity in treating these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach in referral centers with surgeons specialized in this disease who may coordinate treatment; this significantly improves results. Finally, at present time, acute pancreatitis treatment must include a wide range of therapeutic possibilities involving various medical departments such as radiology, endoscopy and advanced intensive care aiming to improve results. Implementing the step-up approach treatment as an alternative to direct surgery for these patients is likely to improve results, although more quality studies are needed to confirm this aspect.

Please cite this article as: Busquets J, Peláez N, Secanella L, Darriba M, Bravo A, Santafosta E, et al. Evolución y resultados del manejo quirúrgico de 143 casos de pancreatitis aguda grave en un centro de referencia. Cir Esp. 2014;92:595–603.