Empyema is one of the most severe complications that can develop after pneumonectomy.1 Evidence of this complication usually appears either immediately after surgery (with bronchopleural fistula and/or infection of the cavity) or instead after several months. Open thoracostomy, which is currently being performed less frequently thanks to less aggressive treatments, is a procedure that provides rapid patient recovery and clear improvement in general status. The progressive reduction in size of the cavity enables it to be later closed with free grafts and resolves one of the most serious complications found in our specialty.2

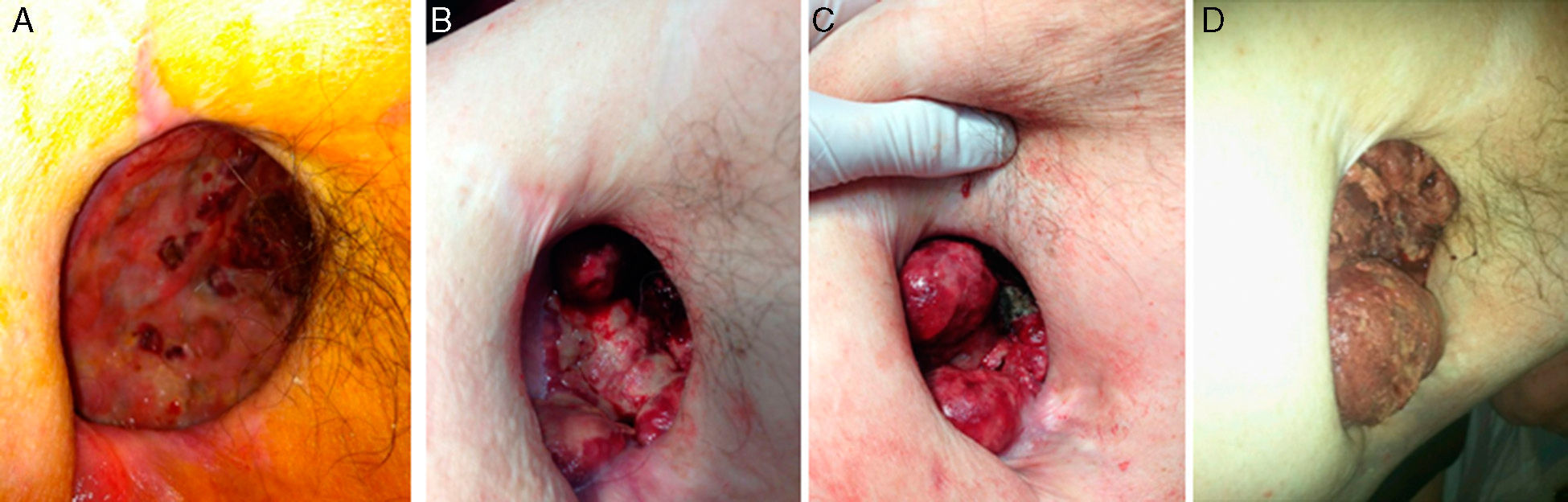

We present the case of a 60-year-old male patient with a history of right pneumonectomy 20 years earlier due to squamous carcinoma of the right upper lobe, with no subsequent treatment. He had been disease-free at annual follow-up studies for 10 years. Two years ago, after an episode of abdominal pain and massive rectal bleeding with hemodynamic instability that required emergency laparotomy and colon resection, the patient presented clinical-radiological semiology of empyema in the pneumonectomy cavity. A microbiological study confirmed the diagnosis as well as abundant bloody/purulent pleural effusion; thus, after chest drainage, we decided to perform open window thoracostomy with daily ambulatory dressing changes. The patient's clinical progress was satisfactory, with good healing of the thoracostomy after the application of platelet factors (Fig. 1A). After the confirmation by computed tomography (CT) of the absence of neoplastic disease and given the improvement of the thoracostomy, we proposed to the patient a procedure for closure with muscle/skin pedicle flap and later free skin graft.

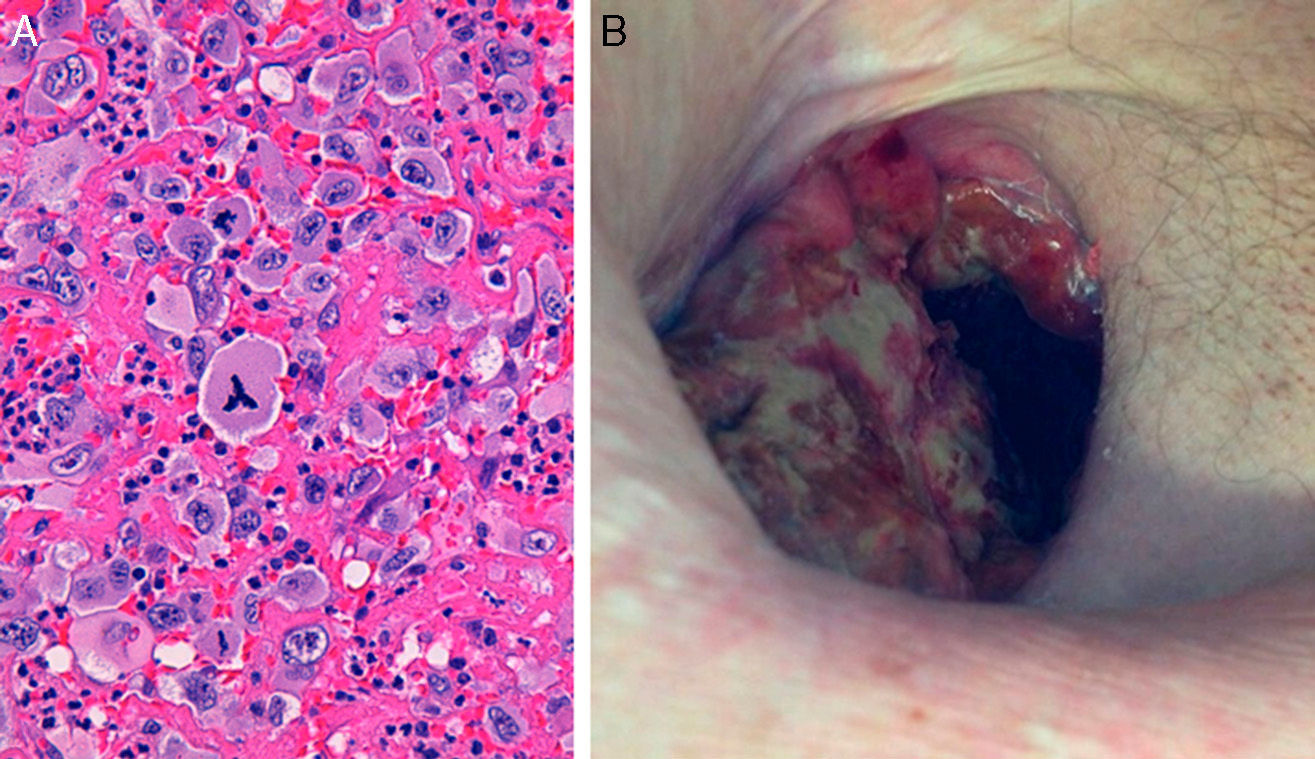

Prior to closure, the patient began to have profuse bleeding through the thoracostomy, and we identified rapidly growing ulcerous masses that were friable and bled spontaneously, accompanied by progressive anemia (Fig. 1B–D). A histology series demonstrated chronic inflammation with no signs of malignancy, except for one that demonstrated the presence of abundant anaplastic large cells surrounded by fibrous connective tissue. Immunohistochemistry confirmed the phenotype of T cells with positivity for CD30, CD4 and EMA, but negative for ALK, CD20, CD79b, S-100 and granzyme B, which was diagnostic for ALK-negative anaplastic lymphoma (Fig. 2A). Thoracic and abdominal CT, aspiration and bone marrow biopsy ruled out further disease, so the diagnosis was extranodal ALK-negative anaplastic lymphoma. Combined treatment was initiated with radiotherapy and CHOP1 (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) therapy, which led to rapid remission and progressive disappearance of the tumors (Fig. 2B). Despite this, the patient experienced progressive clinical deterioration resulting in death caused by his declining condition and progression of his disease.

Extranodal ALK-negative anaplastic lymphomas are very uncommon.3 We present the case of a patient with extranodal anaplastic lymphoma in the region of an open thoracostomy performed more than 20 years before.

Very few cases have been reported of this type of lymphoma related with breast implants in patients with a history of mastectomy due to neoplasm.4 As described in these cases and in our own patient, diagnosis is difficult because symptoms are non-specific, including infection, bleeding, seroma (in the case of breast implants) and/or redness of the area. In our case, the manifestation was diffuse bleeding in the cavity that was recurrent and the formation of clots but no histology of malignancy prior to the closure of the thoracostomy.5 The histologic diagnosis is also difficult because this pathology can simulate chronic inflammation due to the presence of fibroblasts; this was observed in our patient, as several repeated histologic samples were required to reach the definitive diagnosis. The presence of infection in the case of an open thoracostomy is common and, for this reason, the diagnosis of malignancy is also more difficult.

Following the same treatment guidelines as in lymphoma associated with breast implants, our patient initiated treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and the lesions quickly disappeared. Aladily et al.6 differentiated between 2 groups of anaplastic large-cell lymphomas: those associated with a tumor mass or those without. They reported that patients with visible tumor lesions had a poorer prognosis, as was the case of our patient.7 We believe that it is a very rare case with quite an unusual outcome in open thoracostomy or thoracic window.

AuthorsStudy design, data acquisition and collection, analysis and interpretation of results, composition of the article, critical review and approval of the final version: R. Ramos.

Data acquisition and collection, analysis and interpretation of results, critical review and approval of the final version: A. Ureña.

Data acquisition and collection, analysis and interpretation of results: S. Martinez, J.A. Spuch and R.O. Vallansot.

Please cite this article as: Ramos R, Ureña A, Martinez S, Spuch JA, Vallansot R. Linfoma anaplásico de célula grande sobre cavidad de toracostomía abierta. Cir Esp. 2015;93:670–672.