For distal pancreatectomy, there are 2 competing spleen-preserving techniques: one that preserves the splenic vessels1; and the Warshaw technique, in which the splenic vessels are ligated at their origin and resected while preserving the left gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels.2 The disadvantages of this latter technique are associated with immediate complications related with inadequate perfusion of the spleen (infarction) and later complications involving the appearance of varices along the gastric wall, which theoretically present the risk for a gastric bleeding, and increased spleen size, which entails the risk for hypersplenism with haematological alterations.

Case ReportThe patient is a 37-year-old woman with a history of distal pancreatectomy without preservation of the splenic vessels (Warshaw technique) in 2008, due to a benign solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. During follow-up, the patient was sent to the haematology department to study and monitor pancytopenia (platelet count 950000/l [normal: 130000–400000], leukocytes 2100/l [normal: 4000–11000], haemoglobin 96g/l [normal: 120–170]). In 2010, a computed tomography (CT) scan detected a 17cm splenomegaly and collateral circulation in the gastrohepatic ligament, gastrosplenic ligament and in the thickness of the gastric walls. The persistent haematological alterations, which included severe thrombocytopenia, required another CT scan in February 2014, which revealed a very significant increase in the number and size of the oesophagogastric, gastrohepatic and gastrosplenic varices, a permeable portal vein and splenomegaly measuring 17cm (Fig. 1). Using gastroscopy, gastric varices in the fundus and greater curvature were observed.

The admission workup before surgery showed: platelet count 106000/l, leukocytes 2200/l and haemoglobin 100g/l. Laparoscopic splenectomy was performed without incident; the patient was discharged four days after surgery. In the postoperative period, normalisation was observed in the blood series (platelets 362000/l, leukocytes 6000/l and haemoglobin 103g/l).

The Warshaw workgroup has published the results of this operation in 158 patients (in open surgery).2 Three patients (1.9%) required reoperation with splenectomy 3, 14 and 100 days later due to splenic infarction. With a mean follow-up of 4.5 years (range: 0–21 years) none of the patients presented gastrointestinal bleeding or hypersplenism. Radiological follow-up with CT was possible in 65 patients, and evidence of gastric varices and splenic infarction was observed in 25% and 30% of patients, respectively. Miura et al.3 published a study of 10 patients who had undergone the Warshaw technique, with an open approach, and reported in a 52-month follow-up an incidence of perigastric and submucosal varices of 70% and 20%, respectively; one patient presented gastrointestinal bleeding 6.5 years after central pancreatectomy. Tien et al.4 studied 37 prospective patients with the Warshaw technique. With a mean follow-up of 45.3 months, the incidence of varices was 37.8%, which caused no haemorrhage. Butturini et al.5 analysed 43 patients who underwent laparoscopic approaches. Twelve months after surgery, the frequency of gastric varices and thrombocytopenia with the Warshaw technique was 60% and 20%, respectively, and with the splenic vessel-preserving technique it was 21.7% and 13%, respectively.

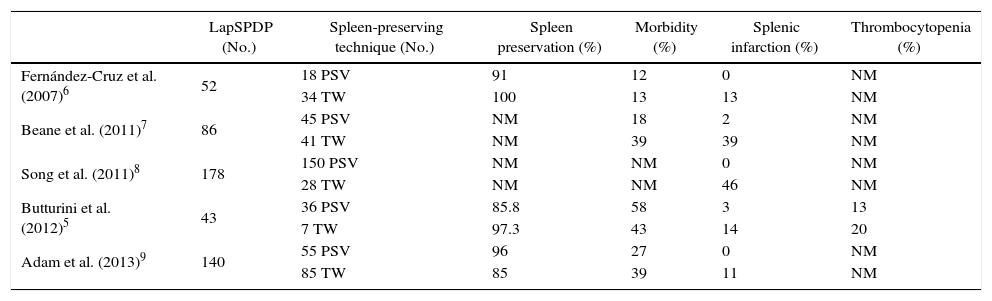

Table 1 presents the complications of the series that compare spleen-preserving techniques.6–9 The analysis of the results of these experiences suggests that, after spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy, regardless of the open or laparoscopic approach and preservation or not of the splenic vessels, the presence of gastric varices is not uncommon. This incidence is notably superior with the Warshaw technique. The reasons for the appearance of these complications with the preservation of the splenic vessels would include surgical trauma and the existence of local complications, such as peripancreatic collections and pancreatic fistula. This analysis also indicates that the risk of a gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to gastric varices is minimal.

Complications of LapSPDP.

| LapSPDP (No.) | Spleen-preserving technique (No.) | Spleen preservation (%) | Morbidity (%) | Splenic infarction (%) | Thrombocytopenia (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández-Cruz et al. (2007)6 | 52 | 18 PSV | 91 | 12 | 0 | NM |

| 34 TW | 100 | 13 | 13 | NM | ||

| Beane et al. (2011)7 | 86 | 45 PSV | NM | 18 | 2 | NM |

| 41 TW | NM | 39 | 39 | NM | ||

| Song et al. (2011)8 | 178 | 150 PSV | NM | NM | 0 | NM |

| 28 TW | NM | NM | 46 | NM | ||

| Butturini et al. (2012)5 | 43 | 36 PSV | 85.8 | 58 | 3 | 13 |

| 7 TW | 97.3 | 43 | 14 | 20 | ||

| Adam et al. (2013)9 | 140 | 55 PSV | 96 | 27 | 0 | NM |

| 85 TW | 85 | 39 | 11 | NM |

LapSPDP: laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy; NM: not mentioned; PSV: preservation of splenic vessels; TW: Warshaw technique.

In a recent study including 140 patients who underwent laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy at 2 hospitals, one in Barcelona and another in Burdens, intraoperative and morbidity results were compared between splenic vessel preservation and the Warshaw technique. The splenic vessel-preserving technique was successful in 96.4% and in 87% with the Warshaw technique. Splenic infarction was observed in 10.5% of the patients with the Warshaw technique, which required splenectomy in 4.5% of the cases.

An increase in the size of the spleen and gastric varices is frequent with the Warshaw technique, but the haematologic complications secondary to hypersplenism are uncommon. When this complication appears with anaemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, patients should be treated with splenectomy, choosing once again the laparoscopic approach. The surgical indication of the case that we present was not due to the presence of gastric varices, but instead because of persistent thrombocytopenia.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Cruz L, Pelegrina A. Trombocitopenia severa después de una pancreatectomía distal con preservación esplénica y resección de los vasos esplénicos por laparoscopia. Cir Esp. 2015;93:668–670.