Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed surgeries. High-grade dysplasia (HGD) in the cystic duct resection margin is uncommon after cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis (<0.1%) or acute cholecystitis (1%), and it is considered a precursor of gallbladder and bile duct cancer.1,2 Therefore, when there is a finding of dysplasia, it is necessary to rule out concomitant tumor pathology, mainly multifocal biliary tumors (biliary intraductal papillary neoplasm, gallbladder adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma).2 However, when faced with an isolated HGD with no clear signs of invasion, there is no therapeutic consensus.3

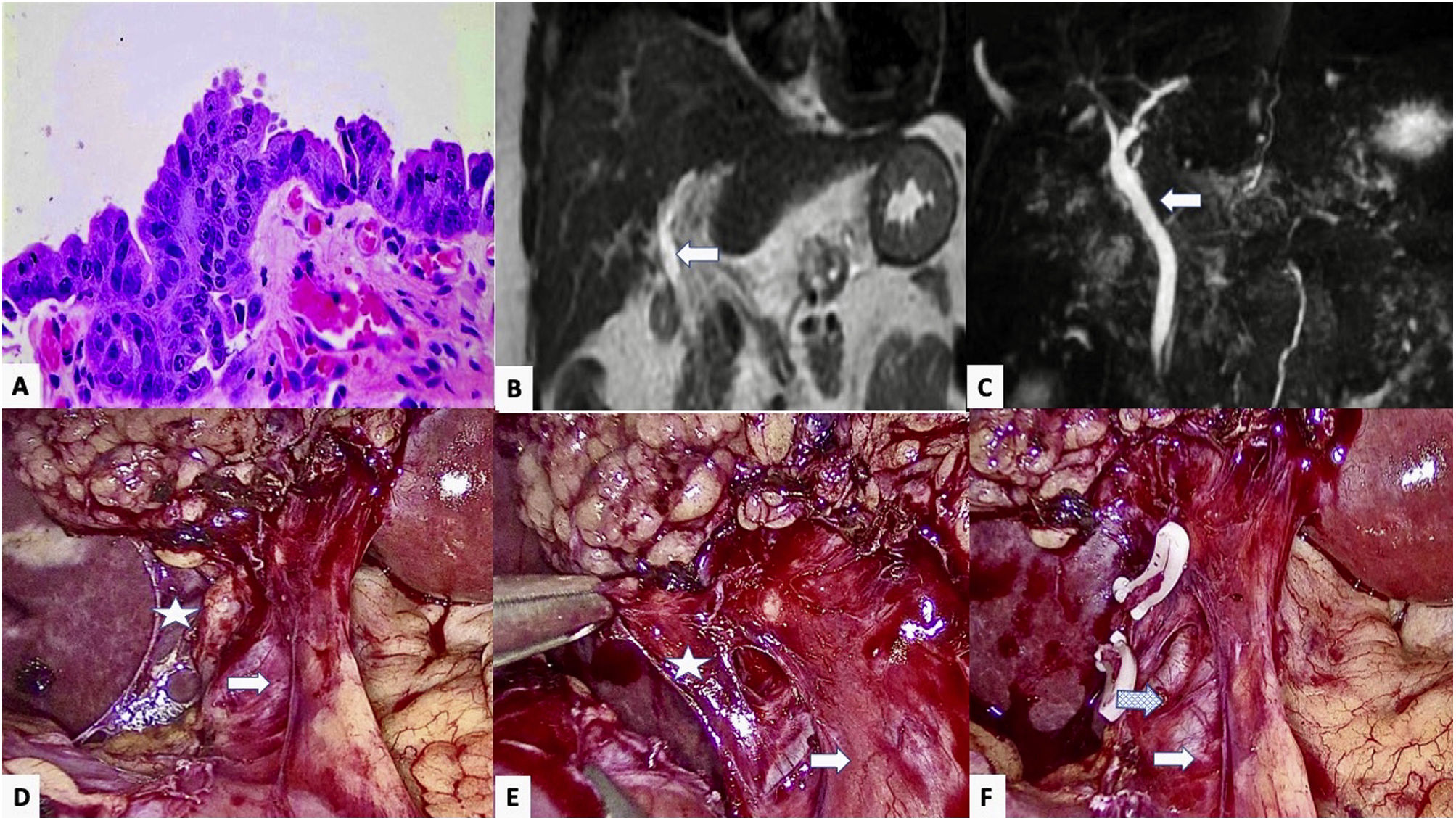

We present a 44-year-old woman with a medical history of multiple sclerosis, bone marrow transplant for acute myeloid leukemia, and cholelithiasis with various episodes of biliary colic over the course of a year, for which she underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (performed without incident). The histopathological study revealed a 2-mm high-grade dysplasia (high-grade biliary intraepithelial neoplasm) in the resection margin of the cystic duct, yet no involvement of the gallbladder (Fig. 1A). On physical examination, the patient presented no abdominal pain or jaundice, nor did she report weight loss. The blood work-up was normal, showing no changes in liver enzymes or bilirubin, and tumor marker levels were normal (CEA 3.09 ng/mL, Ca 19.9 18.80 U/mL). An MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of the liver detected no space-occupying lesion (SOL), pathological lymphadenopathies, or dilation of the bile duct (Fig. 1B and C).

High-grade epithelial dysplasia in the cystic duct resection margin of the cholecystectomy specimen, showing loss of nuclear polarity and intense atypia with nuclear hyperchromatism, irregularity and enlargement; B and C) Main bile duct (Arrow) in coronal MRI slices in T1 (B) and T2 (C), with no observed stenosis or dilatation; D and E) Laparoscopic view, showing the main bile duct (arrow) and the stump of the cystic duct (Star) prior to its surgical resection; F) Image after resection of the cystic remnant, showing the main bile duct (arrow) with associated varicose vein (dotted arrow).

Based on the histology report and the absence of distant disease, the multidisciplinary committee ruled out any further diagnostic studies (CT, ERCP) and proposed a surgical intervention for the re-resection of the cystic margin. The procedure was laparoscopic and entailed dissection and division of the cystic remnant, proximal to the bile duct (Fig. 1D and F). The intraoperative study of the resection margin (1 × 0.6 × 0.1 cm) as well as the re-resection of the cystic gland showed no residual dysplasia or malignancy. The postoperative period was uneventful. One month after surgery, the follow-up (MRCP) revealed nothing of interest.

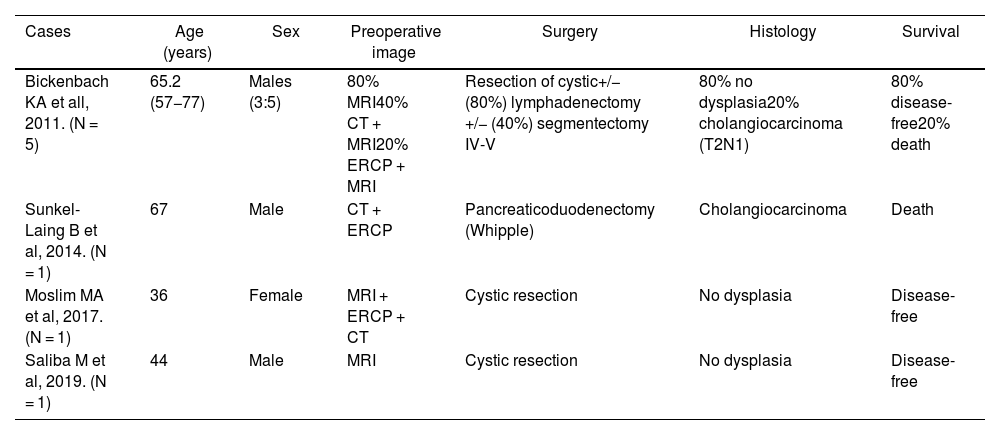

The appearance of HGD in the cystic margin after cholecystectomy is a rare finding (0.2%–1%).3,4 Its importance lies in the potential progression to carcinoma (cholangiocarcinoma in the bile duct or gallbladder adenocarcinoma), as it is a common precursor (69% of cases) and both have an ominous prognosis with invasion.3,4 If the diagnosis of malignancy is confirmed, surgical treatment must be aggressive and include: bile duct resection; hepatectomy of segments IVb and V; and lymph node dissection of the portal, perihilar, and gastrohepatic ligament nodes.1 Some groups have described a correlation of HGD with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (13%–20%) and also report that that the main prognostic factor for survival was surgical margin involvement.4–6 Due to the multifocal nature of tumors in this location, exploration of the bile duct is mandatory, requiring resection in many cases (Table 1).7

Distribution of the HGD cases described in the literature.

| Cases | Age (years) | Sex | Preoperative image | Surgery | Histology | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bickenbach KA et all, 2011. (N = 5) | 65.2 (57−77) | Males (3:5) | 80% MRI40% CT + MRI20% ERCP + MRI | Resection of cystic+/− (80%) lymphadenectomy +/− (40%) segmentectomy IV-V | 80% no dysplasia20% cholangiocarcinoma (T2N1) | 80% disease-free20% death |

| Sunkel-Laing B et al, 2014. (N = 1) | 67 | Male | CT + ERCP | Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple) | Cholangiocarcinoma | Death |

| Moslim MA et al, 2017. (N = 1) | 36 | Female | MRI + ERCP + CT | Cystic resection | No dysplasia | Disease-free |

| Saliba M et al, 2019. (N = 1) | 44 | Male | MRI | Cystic resection | No dysplasia | Disease-free |

However, the presence of HGD when there is no suspected malignancy is quite rare (0.05%).8,9 In these patients, the main objective, as highlighted by the guidelines of the American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (AHPBA), is to rule out adjacent tumor pathology,10 initially based on intraoperative findings of the previous cholecystectomy, presence of lymphadenopathies, and dilation of the bile duct, gallbladder or biliary tumor. Secondly, after the histological confirmation of HGD, an extension study is necessary with abdominal CT and MRCP. Tumor markers (CEA, CA 19.9) could help guide the diagnosis. As previously mentioned, this type of neoplasm tends to be multifocal, so a diagnostic ERCP could be appropriate.

Preoperative diagnostic tests frequently do not provide relevant information. Thus, the question that remains is whether radical surgery is necessary or whether cystic resection and close surveillance would suffice in the absence of diagnosis or evidence of malignancy. In this context, the role of multidisciplinary committees becomes essential. Until now, radical surgery with excision of the bile duct has been considered the appropriate therapy. However, the most recent published papers advocate a conservative approach with close monitoring, either with or without surgical treatment.1,4 Due to its importance, this decision must always be made with the patient, most whom opt for surgical treatment, as described in other series.4 The diagnosis is histological, based on the detection of cells with HGD, suggesting that the disease-free resection margin should be at least 5 mm, in prognostic terms.

In our case, we decided to reoperate with minimally invasive surgery, resecting the cystic remnant and confirming the absence of margin involvement with an intraoperative sample. This latter technique is not mandatory due to its low diagnostic yield (fibrosis, inflammatory changes), but it helps determine the prognosis and extension of surgery.3 Regarding postoperative follow-up, the data in the literature are ambiguous. Nevertheless, a follow-up of at least 5 years is recommended, similar to biliary carcinoma, with tumor markers (CEA, CA 19.9) and abdominal ultrasound/CT scan every 6 months for 2 years, and annually thereafter.

In conclusion, HGD of the cystic remnant with no evidence of malignancy after cholecystectomy is a rare pathology. However, it is necessary to rule out its association with biliary tumor pathology, and the treatment of choice includes cystic resection and close postoperative follow-up.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflicts of interests.

The authors would like to thank the General and Digestive Surgery Service and the Abdominal Organ Transplantation Department of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre.