The appearance of internal hernias after bariatric surgery is relatively frequent (between 0.4% and 8.8%).1 Intestinal loops can become herniated through the defects created during reconstruction in certain types of bariatric surgery, which become enlarged after postoperative weight loss.2 These hernias can cause digestive tract and/or vascular obstructions, but lymphatic obstructions are less frequent without clear, associated symptoms.

Our patient is a 38-year-old woman with no history of interest. In 2017, due to grade IV obesity and a body mass index (BMI) of 49.77kg/m2, she underwent laparoscopic gastric bypass (LGB) with a 150cm antecolic loop and a 60cm biliopancreatic loop. The defects (Petersen space and mesentery) were closed with 3/0 polybutester barbed suture. The patient experienced adequate weight loss, but, 8 months later, she reported postprandial epigastric pain that was self-limiting for a duration of 20–30min and unrelated to the type of oral intake. Blood tests, gastroscopy, gastrointestinal transit study, computed tomography (CT) scan and abdominal ultrasound were performed, detecting no disease except cholelithiasis.

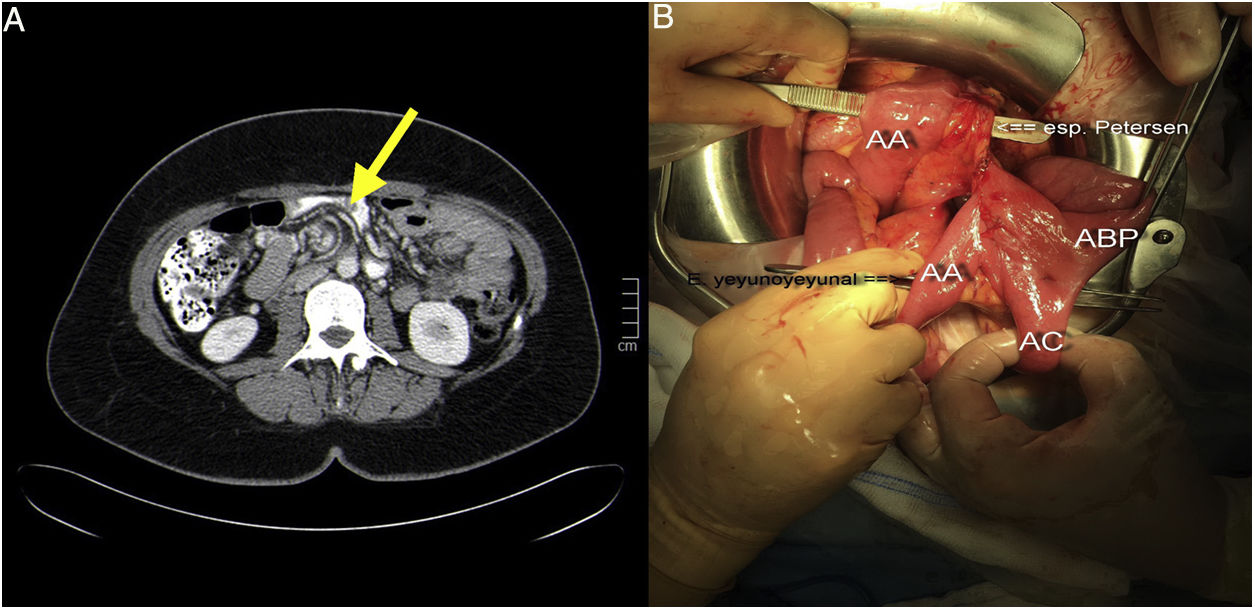

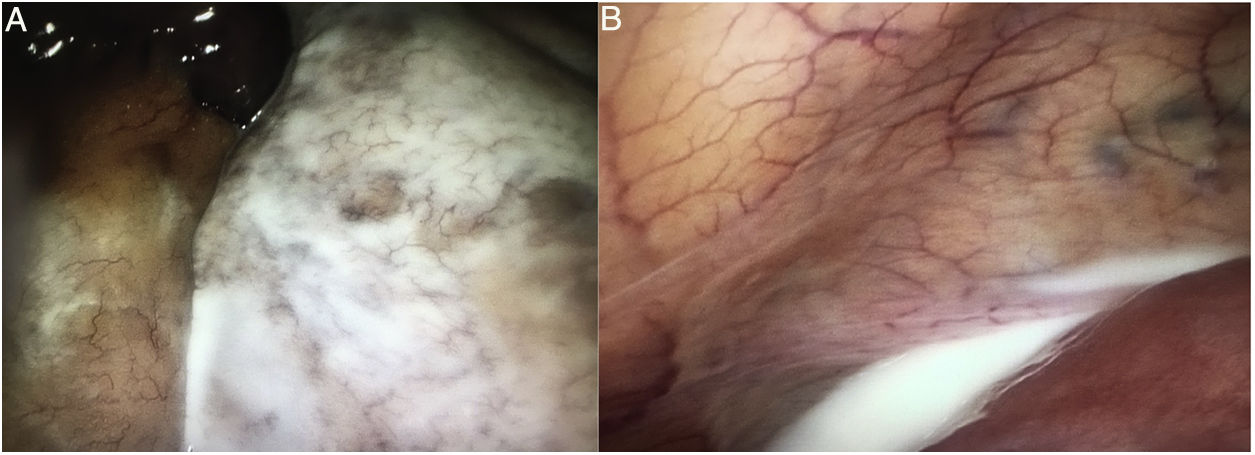

The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (BMI: 36.14kg/m2) 10 months after LGB, with no intraoperative findings of interest. After this surgery, the patient continued to have the same symptoms, so the imaging tests were repeated. The new CT study found a whirl of mesenteric vessels in the right hemiabdomen and rotation of the biliopancreatic loop, with no signs of obstruction, intestinal suffering, ascitic fluid or peritoneal thickening (Fig. 1A). Given the persistent symptoms and the new findings, laparoscopic surgery was scheduled 10 days after the CT results (13 months after LGB; BMI: 33.79kg/m2). Significant thickening was found in the mesentery of the small intestine in the center of the abdomen, which was whitish in color, yet other mesenteric areas were normal in thickness and coloration (Fig. 2A). Likewise, the presence of chylous fluid (Fig. 2B) between loops and in the pelvis was observed (microbiological study: negative; ascitic liquid triglycerides: 4995mg/dL). The cause was found to be a hernia through the Petersen space (Fig. 1B) containing a long segment of common loop and a large part of the biliopancreatic loop. As it was impossible to resolve the hernia safely by laparoscopy, conversion to open surgery was required for reduction and devolvulation of the herniated loops, with closure of the Petersen space using continuous 3/0 polypropylene suture. The postoperative progress was favorable, and the patent was discharged on the second day. Currently the patient is free of symptoms.

Chylous ascites or chyloperitoneum is an uncommon disease with little presence in the medical literature since Morton described it in 16913 after performing paracentesis in a pediatric patient with disseminated tuberculosis. It is defined as the presence of ascitic fluid with a high content of fat (triglycerides), normally above 200mg/dL.4 To date, very few reports have been published of chyloperitoneum associated with internal hernia after LGB,5,6 most of which are due to a hernia through the mesenteric button-hole of the jejunojejunal anastomosis. Although there have been cases7 of chyloperitoneum associated with Petersen's hernia after Roux-en-Y reconstructions due to oncologic gastric surgery, our case has the peculiarity of occurring after bariatric surgery.

The etiology of chyloperitoneum is well known, and among the factors that determine it are congenital causes, fibrotic causes (hematological diseases, sarcomas and metastasis) and acquired causes.4 Among the latter are those that cause increased lymph production, such as cirrhosis (the most common cause next to fibrotic causes in our setting) and heart disease, and those that cause a disruption or obstruction of the thoracic duct, such as trauma injuries, abdominal surgeries, infections (filariasis, tuberculosis) and radiotherapy.

The diagnosis of chyloperitoneum after bariatric surgery requires a high degree of suspicion, supported by the finding of free peritoneal fluid on ultrasound and abdominal CT. However, the main study used is lymphoscintigraphy because it shows the lymphatic anatomy and locates chyle leaks. Diagnostic confirmation requires paracentesis for biochemical analysis of the fluid obtained, which usually detects a high concentration of triglycerides, alkaline pH, proteins >3g/L and cells, with a predominance of lymphocytes.

In our patient, none of the symptoms or test findings guided the diagnosis toward chyloperitoneum, but rather toward chronic abdominal pain and the progressive development of an internal hernia due to weight loss as the first etiological cause, which is why exploratory laparoscopy was indicated.8 The extrinsic compression of the lymphatic vessels of the mesentery explained the appearance of chyloperitoneum.

For the treatment of chyloperitoneum, its cause should be considered, although it is usually based on parenteral nutrition associated with somatostatin or octreotide, diets low in fat with medium-chain triglycerides, since these go directly to the blood circulation without passing through the lymph.9 Surgery is not the initial therapeutic option.

When treating patients with previous laparoscopic gastric bypass who present abdominal pain, Petersen hernia should always be included in the differential diagnosis, even when radiology tests are negative. Closure of the orifices with potential for herniation during the bariatric procedure may reduce the incidence of this complication.10 The laparoscopic approach in cases of hernia is recommended, whenever feasible.

Please cite this article as: del Valle Ruiz SR, González Valverde FM, Tamayo Rodríguez ME, Medina Manuel E, Albarracín Marín-Blázquez A. Quiloperitoneo incidental asociado a hernia de Petersen en paciente operada de bypass gástrico laparoscópico. Cir Esp. 2019;97:351–353.