Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent condition that affects 10% of women of reproductive age. In experimental models, estrogens are necessary to induce or preserve endometriomas, which can spread directly and appear in abdominal surgical scars after endometriosis interventions. The most accepted theory for the pathogenesis is so-called retrograde menstruation, with an immune system incapable of destroying the implanted cells. Endometriosis in distant parts of the body can be explained by lymphatic and vascular migration, providing a unique example of benign proliferation and metastasis. Pesticides, plastic containers used for microwave cooking and dioxin have all been linked to this disease.1 At the genetic level, an association has been demonstrated between endometriosis and the mutation of chromosomes 10q262 and 7p15.2.3

Horton et al. reviewed 29 articles describing 455 patients diagnosed with endometriosis in the abdominal wall. Average age was 31.4 years; 96% presented a mass, 87% reported pain, and 57% presented cyclical symptoms. A previous cesarean section was related to the condition in 57% of cases, while 11% had undergone hysterectomy. The interval between the clinical presentation reported by patients and definitive surgery was 3.6 years, and postoperative recurrence was 4.3%. The most common presentation was a painful mass, and surgical treatment resulted in healing in more than 95% of cases.4 We present the clinical case of a 49-year-old woman who consulted for the progressive growth of a painful mass that had remained stable for 7 years. The mass was located on the lateral side of the left lower limb. The patient had undergone liposculpture in 2005.

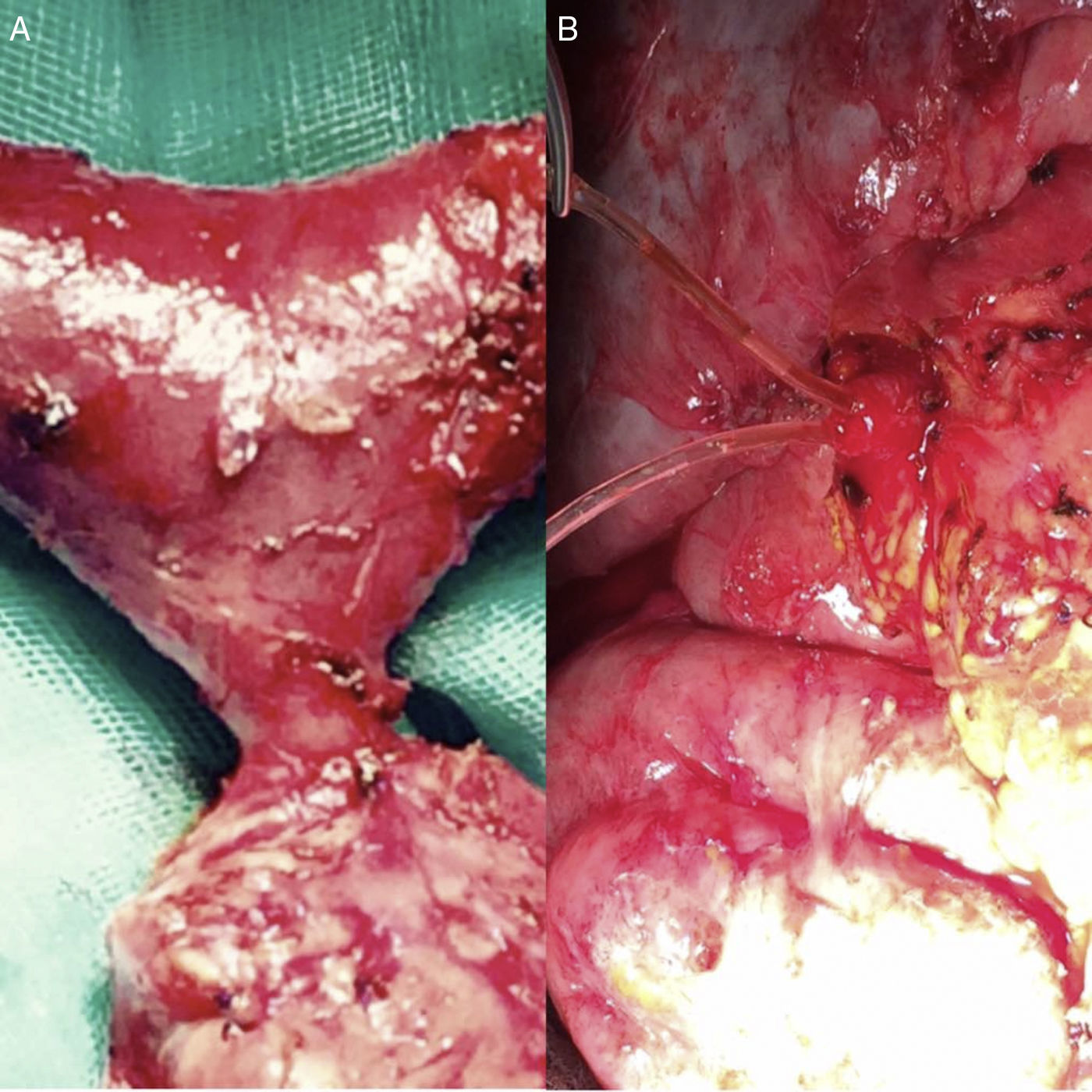

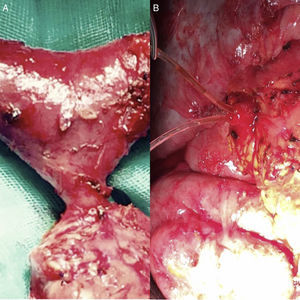

On physical examination, between the left vastus lateralis muscle and the anterior rectus muscle of the thigh, a mass was palpable. It measured 1.5cm at its maximum diameter, was fusiform and well defined, but was probably underlying the muscular aponeurosis as it was not very mobile; its consistency was similar to that of an enlarged adenopathy. The main symptom was pain on palpation of the described lesion, which is unusual in most frequently biopsied tumors. We performed a scheduled surgical intervention in the major outpatient surgery setting. We anesthetized the skin and later the aponeurosis. It was necessary to open the fascia wrapping the muscle bundle to access the lesion described, which we found within the thickness of the fibers, showing apparently good delimitation. It was dark pink in color, reminiscent of a lymph node, but its texture was more friable than usual, with no clear fibrous capsule, apparently glandular to the touch with the forceps, with a well-defined vascular pedicle that was divided with diathermy. We conducted exeresis, which was limited to the lesion described, and closed by planes.

The pathology report described a lesion compatible with endometriosis (Fig. 1) with malignant transformation to very well-differentiated grade I endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2). The immunohistochemical analysis was positive for vimentin (endometrial adenocarcinoma marker) and cytokeratin 7, with foci of moderately positive progesterone and estrogen receptors (2%). The markers cytokeratin 20, inhibin and WT1 (ovary and mesothelium markers), TTF1 (lung and mesothelium marker) and GATA 3 (breast marker) were negative. An extension study was performed through complete gynecological examination and positron emission tomography, with no finding of lesions in other areas. Extension of surgical margins was programmed under general anesthesia, and the definitive pathology study reported free margins. The patient continues in outpatient follow-up.

Endometriomas in the thigh are highly uncommon, although there are descriptions in the literature, and they simulate soft tissue tumors.5

1% of endometriomas can undergo malignant processes, which can settle in surgical scars.6 The recent change in symptoms should make us suspect a malignant transformation. In the case of our patient, an indolent tumor of limited size from 7 years ago became a painful lesion that had progressively increased in size in recent weeks.7 Cesarean section is the surgical procedure most frequently associated with extrapelvic endometriosis, with an estimated frequency of 0.03%–1%.8 In our case, liposculpture performed years earlier could have been related to the atypical location of the lesion, through a mechanism of cell migration.6 We should suspect the diagnosis of an endometrioma in the abdominal wall or muscle in women of childbearing age presenting a well-defined palpable mass that is painful under pressure and which the patient reports as being present for several years.

The malignization of an endometrioma is highly uncommon and is currently the subject of genomic research.7 This pathology should be suspected when the tumor grows and changes its symptoms, causing localized pain due to compression of the surrounding tissues. The treatment of choice is complete excision of the lesion with free edges. The use of electrocoagulation can destroy the lesion and devitalize the tissue, while also making the pathology analysis difficult.

Please cite this article as: Pareja López Á, Martínez Ortiz F, Alonso Fernández MA. Endometrioma malignizado localizado en el miembro inferior. Cir Esp. 2018;96:173–174.