Multimodal rehabilitation (MMRH) programmes in surgery have proven to be beneficial in functional recovery of patients. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of a MMRH programme on hospital costs.

MethodA comparative study of 2 consecutive cohorts of patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery has been designed. In the first cohort, we analysed 134 patients who received conventional perioperative care (control group). The second cohort included 231 patients treated with a multimodal rehabilitation protocol (fast-track group). Compliance with the protocol and functional recovery after fast-track surgery were analysed. We compared postoperative complications, length of stay and readmission rates in both groups. The cost analysis was performed according to the system “full-costing”.

ResultsThere were no differences in clinical features, type of surgical excision and surgical approach. No differences in overall morbidity and mortality rates were found. The mean length of hospital stay was 3 days shorter in the fast-track group. There were no differences in the 30-day readmission rates. The total cost per patient was significantly lower in the fast-track group (fast-track: 8107±4117 euros vs control: 9019±4667 euros; P=.02). The main factor contributing to the cost reduction was a decrease in hospitalisation unit costs.

ConclusionThe application of a multimodal rehabilitation protocol after elective colorectal surgery decreases not only the length of hospital stay but also the hospitalisation costs without increasing postoperative morbidity or the percentage of readmissions.

Los programas de rehabilitación multimodal (RHMM) en cirugía han demostrado un beneficio en la recuperación funcional de los pacientes. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar el impacto de un programa de RHMM en los costes hospitalarios.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo comparativo de cohortes consecutivas de pacientes intervenidos de cirugía colorrectal electiva. En la primera cohorte analizamos 134 pacientes que recibieron un control postoperatorio convencional (grupo control). En la segunda cohorte se incluye a 231 pacientes tratados con un programa de RHMM (grupo RHMM). Se analiza el cumplimiento del protocolo y la recuperación funcional de los pacientes del grupo RHMM. Se comparan las complicaciones postoperatorias, la estancia hospitalaria y los reingresos en ambos grupos. El análisis de costes se ha basado en la contabilidad analítica del centro.

ResultadosLas características demográficas y clínicas de los pacientes fueron similares entre grupos. No encontramos diferencias en la morbimortalidad global. La estancia media postoperatoria fue 3 días menor en el grupo RHMM. No se observaron diferencias significativas en la tasa de reingresos. Los costes totales por paciente fueron significativamente menores en el grupo RHMM (RHMM: 8.107±4.117 euros vs control: 9.019±4.667 euros; P=0,02). El principal factor que contribuyó a la reducción de los costes fue el descenso de los gastos de la Unidad de Hospitalización.

ConclusionesLa aplicación de un protocolo de RHMM en cirugía electiva colorrectal reduce, no solo la estancia hospitalaria, sino también los costes hospitalarios, sin aumentar la morbilidad postoperatoria ni el porcentaje de reingresos.

In recent years, there has been a slow but steady increase in the use of multimodal rehabilitation (MMRH) programmes (also called “fast track”) proposed by Kehlet1 after elective colorectal surgery. These programmes, which require the coordination of different specialists, are a combination of different perioperative care strategies to reduce surgical stress and facilitate postoperative patient recovery.2–5 The implementation of these measures has reduced hospital stays to 2–4 days without increasing morbidity6,7; additionally, the experience of some authors indicates that such programmes may reduce postoperative complication rates.8,9

In 2005, the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Project (ERAS)10 was published, which combines different strategies for perioperative care based on the best scientific evidence. Since the emergence of the ERAS protocols, several randomised clinical trials and meta-analyses of new proposals for multidisciplinary performance have been published, with the aim of improving the functional recovery of patients following elective colorectal surgery.7,11–13 Although each specific strategy is beneficial in itself for achieving the best results, they should all be used together.14 Furthermore, decreasing hospital stays and, in some cases, reducing postoperative complications must lower hospital costs. However, very few studies have assessed the impact of MMRH programmes on hospital costs after colorectal surgery.15

In March 2006, the Colorectal Surgery unit of the Hospital del Mar in Barcelona launched an MMRH protocol for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. In the analysis of the initial results with a group of 90 patients,16 we showed that MMRH is a safe protocol (as it does not increase complications) that reduces hospital stays to three days.

The aim of this study is to confirm our preliminary results by increasing the number of patients in the MMRH programme and to analyse the impact on hospital costs.

Materials and MethodsStudy DesignA prospective comparative study of two consecutive cohorts of patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

Study PopulationThe MMRH group consisted of 231 patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery between March 2006 and December 2007. The control group included 134 patients who underwent surgery in 2005, before the implementation of the MMRH protocol. Inclusion criteria were all patients undergoing scheduled colon and rectal surgery. No exclusion criteria were established.

The protocol of the MMRH group consisted of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative strategies.16 The preoperative strategies were providing oral and written information about the surgical procedure and the MMRH programme by the surgeon and a nurse from the hospital Colorectal Surgery Unit; performing colon preparation with polyethylene glycol (Bohm Laboratories, S.A.) while administering a hydrocarbon solution (135g carbohydrate in 1000cm3) as enteral nutrition (Edanec®, Abbott Laboratories, S.A.); prescribing a preoperative 6-h liquids and solids fast; providing antibiotic prophylaxis with metronidazole 1g gentamicin 240mg and antithrombotic bemiparin 2500 UI preoperatively and daily postoperatively for 4 weeks. During the intraoperative phase, analgesia was administered through an epidural catheter, and short-acting anaesthetics were used; hydration was performed at an adjusted rate of 6–8ml/kg/h; hypothermia was prevented with temperature-controlled fluid therapy and a heating blanket; and intra-abdominal drains and nasogastric tube placement were avoided. During the postoperative phase, multimodal analgesia was administered, the diet resumed gradually 6h after surgery, and early mobilisation was encouraged.

The most important differential strategies for the control group protocol were as follows. During the preoperative phase, oral communication was only provided by the surgeon; the colon was prepared using Fosfosoda® (Fleet Company Inc., VA, USA) while administering intravenous hydration of 1000ml of 5% dextrose with 60mEq KCl; and preoperative fasting began the night before surgery. During the intraoperative phase, fluid therapy was administered at the discretion of the attending anaesthesiologist at a rate of approximately 10–14ml/kg/h, almost twice the established rate for the MMRH protocol. During the postoperative phase, the diet was resumed according to the surgeon's criterion, usually with the onset of peristalsis.

In both groups, discharge occurred when the patient was able to tolerate a solid diet, had good pain control with oral analgesia and was ambulatory.

VariablesThe demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in each group were compared. Medical and surgical complications occurring within 30 days after surgery in both groups were recorded. The average length of stay and readmission rate per group was also included. The nursing staff or attending physician's compliance with the MMRH programme's protocol for the start of the diet and the withdrawal of fluid therapy was analysed. Tolerance of diet and ambulation were measured as parameters of functional recovery. We analysed the progression of hospital discharge in both groups. The hospital discharge rate per day was studied for each group. Finally, total and specific costs were calculated (per hospitalisation unit, laboratory, radiology, pharmacy, surgical suite and disease) per patient in each group.

Cost AnalysisOur hospital cost accounting provides patient-level details. It is characterised by a “full-costing” system and for basing the allocation of costs to activities on a cost-benefit analysis (CBA).17 This cost analysis system ensures that all of the expenses are shared between all of the episodes. The cost of each episode is the sum of the costs of all variable costs (direct costs) plus the set of general costs charged per activity (indirect costs). The cost information available allows the disaggregation of costs, such as inpatient unit, laboratory, radiology, pharmacy, operating room and disease.

Statistical AnalysisA descriptive and statistical comparison of variables was performed, considering a P-value of less than .05 to be statistically significant. Qualitative variables are expressed in absolute numbers or proportions, and quantitative variables are expressed as the median and range or as the mean and standard deviation. The test of the hypothesis was the Chi-squared test for qualitative ordinal variables (comparison of proportions), Student's t-test for continuous variables when their applicability criteria were met and the Mann–Whitney U test when applicability criteria were not met. All of the data were analysed using SPSS Version 12.0.

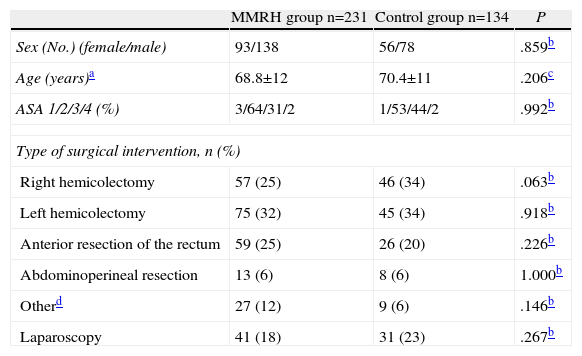

ResultsThere were no differences in the patient characteristics or surgical procedures performed between the two study groups (Table 1).

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients in Each Group.

| MMRH group n=231 | Control group n=134 | P | |

| Sex (No.) (female/male) | 93/138 | 56/78 | .859b |

| Age (years)a | 68.8±12 | 70.4±11 | .206c |

| ASA 1/2/3/4 (%) | 3/64/31/2 | 1/53/44/2 | .992b |

| Type of surgical intervention, n (%) | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 57 (25) | 46 (34) | .063b |

| Left hemicolectomy | 75 (32) | 45 (34) | .918b |

| Anterior resection of the rectum | 59 (25) | 26 (20) | .226b |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 13 (6) | 8 (6) | 1.000b |

| Otherd | 27 (12) | 9 (6) | .146b |

| Laparoscopy | 41 (18) | 31 (23) | .267b |

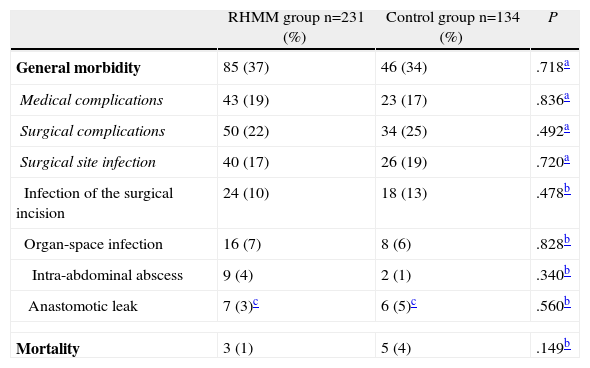

Table 2 shows the overall morbidity of both groups; there were no significant differences between them. This morbidity rate also included patients who were readmitted. We did not observe significant differences when comparing medical and surgical complications. Surgical site infections were analysed separately, and they also showed no differences. Finally, mortality in both groups was less than 5%, and the differences were not statistically significant.

Morbimortality Compared Between the MMRH and Control Groups.

| RHMM group n=231 (%) | Control group n=134 (%) | P | |

| General morbidity | 85 (37) | 46 (34) | .718a |

| Medical complications | 43 (19) | 23 (17) | .836a |

| Surgical complications | 50 (22) | 34 (25) | .492a |

| Surgical site infection | 40 (17) | 26 (19) | .720a |

| Infection of the surgical incision | 24 (10) | 18 (13) | .478b |

| Organ-space infection | 16 (7) | 8 (6) | .828b |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 9 (4) | 2 (1) | .340b |

| Anastomotic leak | 7 (3)c | 6 (5)c | .560b |

| Mortality | 3 (1) | 5 (4) | .149b |

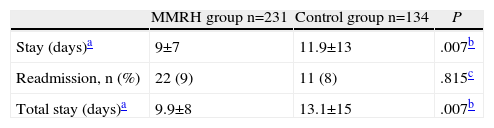

Table 3 shows a statistically significant decrease of three days in the average hospital stay of patients in the MMRH group compared with control patients; however, no differences were found in the percentage of readmissions. The three-day decrease was maintained when analysing the total stay as the sum of the initial stay and the readmission stay.

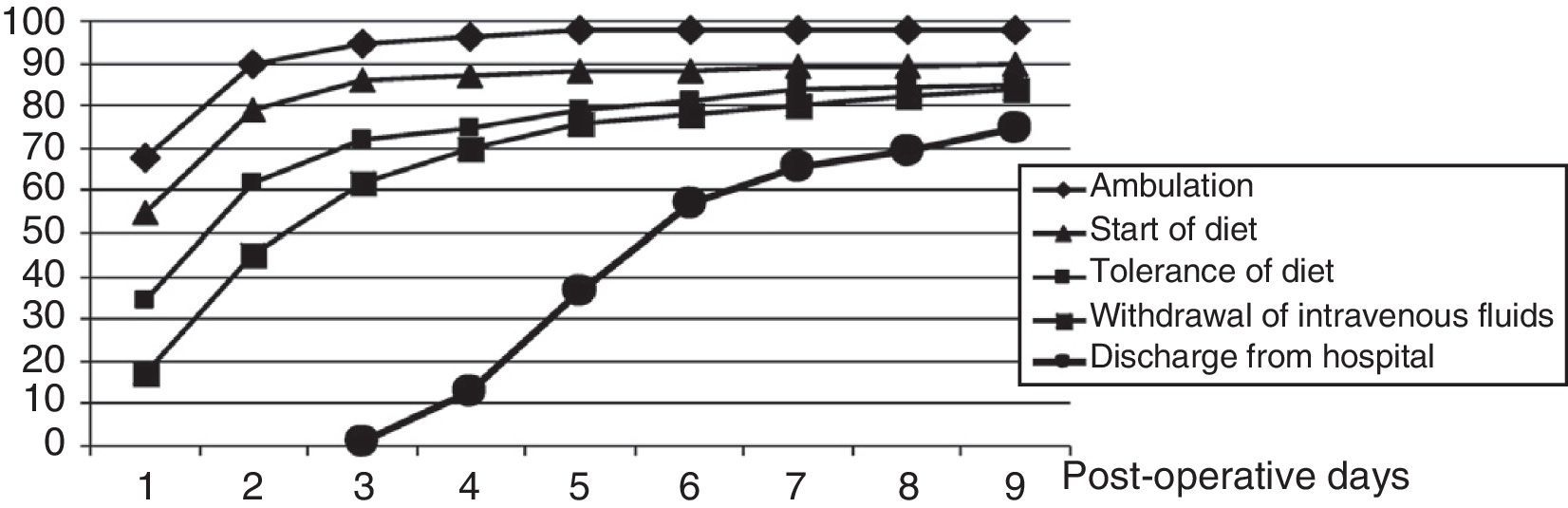

Fig. 1 shows an analysis of different aspects included in the programme to reflect the MMRH protocol compliance and functional recovery of patients, such as the beginning of ambulation and diet, diet tolerance and intravenous fluid therapy withdrawal. The percentage of patients discharged on a given postoperative day is also shown. We note that only 55 and 68% of patients started the diet and ambulated, respectively, on the first postoperative day. On the fifth postoperative day, only 37% of patients were discharged, although 80% of the patients met the discharge criteria.

Analysis of protocol compliance (with the items onset of diet and withdrawal of fluid therapy) and functional recovery (with the items tolerance of diet and ambulation) in the MMRH group. The hospital discharge progression rate according to the postoperative day is also shown for the MMRH group.

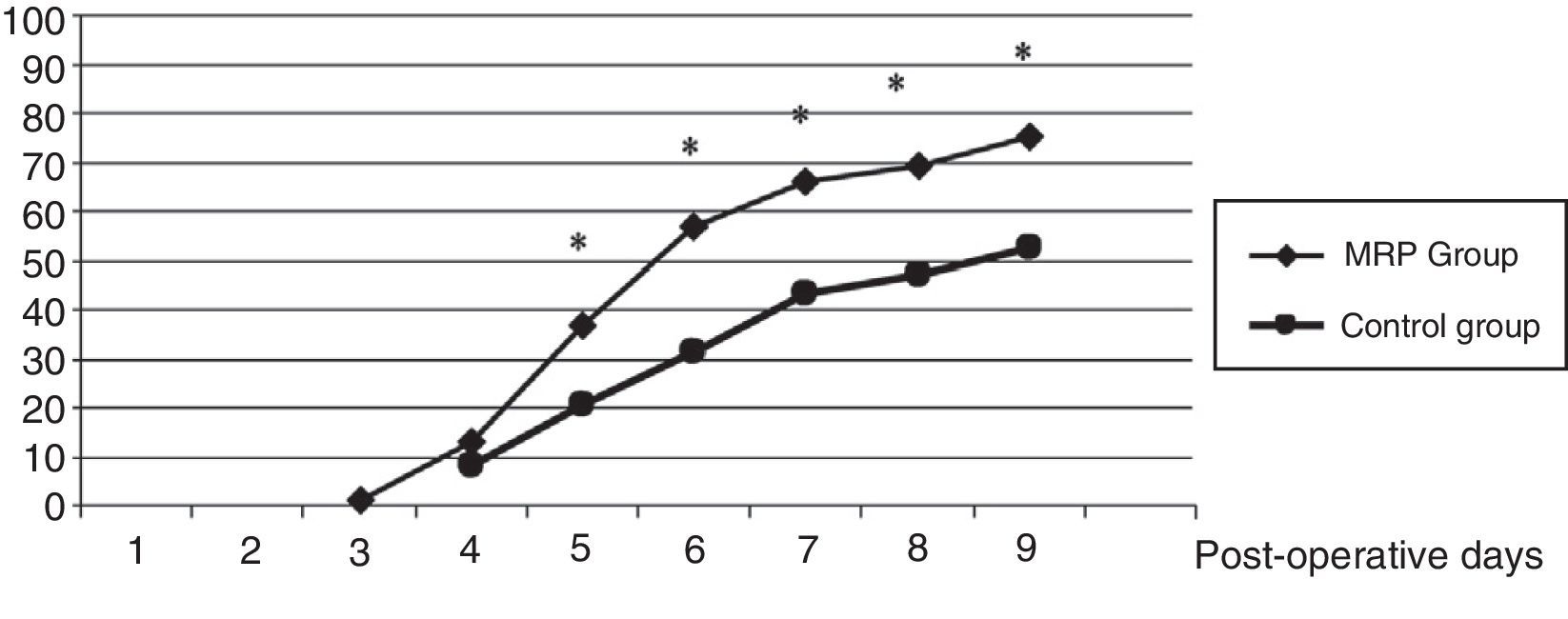

Fig. 2 shows the progression to hospital discharge in the both groups. Statistically significant differences were observed on the fifth postoperative day (37% vs 20%), the sixth postoperative day (66% vs 43%) and the eighth postoperative day (69% vs 47%).

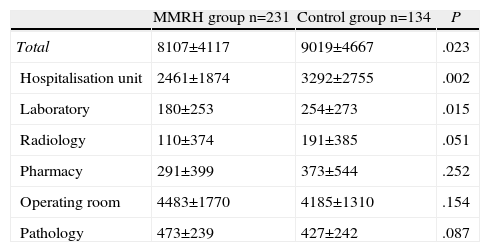

Table 4 shows the hospital costs per patient in each group. We found a significant reduction in total cost of 912 € per patient in the MMRH group compared with the control group. This significant reduction of costs was found mainly for the hospitalisation unit, with a cost decrease of 831 € in the MMRH group. We also observed a significant reduction in laboratory costs. The costs per patient for radiology and pharmacy were also lower in the MMRH group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Costs Per Patient in the MMRH and Control Groups. Mann–Whitney U Test.

| MMRH group n=231 | Control group n=134 | P | |

| Total | 8107±4117 | 9019±4667 | .023 |

| Hospitalisation unit | 2461±1874 | 3292±2755 | .002 |

| Laboratory | 180±253 | 254±273 | .015 |

| Radiology | 110±374 | 191±385 | .051 |

| Pharmacy | 291±399 | 373±544 | .252 |

| Operating room | 4483±1770 | 4185±1310 | .154 |

| Pathology | 473±239 | 427±242 | .087 |

Units: euros.

First, the present study confirms the preliminary results published by our group16 in a series with a larger number of patients included in the MMRH protocol. This protocol is safe, does not increase patient morbidity or mortality and reduces hospital stay by three days compared with conventional perioperative care. These results are also consistent with previous studies and systematic reviews.7–13 Second, this study shows how faster patient recovery is associated with a significant reduction in hospital costs. Although it is obvious, little published work has quantified this cost reduction.

Although the overall morbidity and mortality in this study were similar to that described in other studies on the implementation of MMRH programmes,18,19 we found no differences in postoperative complications between groups. Therefore, we can say that the hospital stay reductions were not caused by reduced morbidity. The impact of MMRH programmes on postoperative morbidity is controversial. In the systematic review by Wind et al.,7 morbidity rates between 8% and 75% were found; however, the differences between groups reached statistical significance only in one study.9 A systematic review of the Cochrane Database13 showed a reduction in overall complications, but the most serious complications did not decrease. The absence of differences in morbidity in our study and in others may be related to several reasons. First, each study used different definitions of complications and different classifications. Second, the need to optimise the implemented protocol in accordance with all the recommendations of ERAS protocols may have minimised differences in morbidity.10 For example, we established a 6h preoperative fast, while the ERAS protocol consensus recommends fluid intake 2h before anaesthetic induction and solid intake 6h20 before anaesthesia. We also need to improve the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting21 by implementing strategies to prevent postoperative ileus, such as administering magnesium hydroxide10 and other prokinetics.19 Currently, we are considering implementing some of these strategies with the intention of improving our protocol. For example, beginning two years ago, patients undergoing colon resection did not receive preoperative bowel preparation, based on the scientific evidence.22 The implementation of all the recommendations recently examined by the ERAS group could significantly reduce postoperative morbidity.23

We have achieved a significant reduction in hospital stay despite a low level of compliance with the MMRH programme. Protocol compliance has been identified as one of the problems of MMRH programmes,13 reflecting the difficulty of changing a traditional protocol and implementing new strategies for perioperative care. However, this problem has hardly been studied. In a previous study, we observed that compliance with a new protocol is initially low but gradually improves, along with the results of the MMRH programme and the experience of the professionals involved.24 Delaney et al.5 also observed that the hospital stay was shorter when these programmes were implemented by experienced surgeons. The difficulty of implementing an ERAS protocol outside clinical trials has been recently investigated by Ahmed et al.25 The authors found that protocol compliance was lower in daily practice compared with compliance during a clinical trial. Interestingly, as in the present study, the clinical results improved despite low compliance. This suggests that greater compliance could further improve postoperative recovery and even reduce morbidity.

Moreover, the reduction to a three-day hospital stay was achieved without increasing the rate of readmission. Reducing inappropriate hospital stay often comes at the expense of increasing the percentage of readmissions. In the study by Basse et al.,26 the average hospital stay was only two days in the MMRH programme, but readmission was necessary in 20% of patients. Our readmission rate since starting the MMRH programme is acceptable, as it does not exceed the 10% recommended by some authors.27

Another aspect that should be discussed is the inability to discharge patients even when they fulfilled the established clinical criteria. This is a very important limiting factor for improving the results. For example, in this study, only 37% of patients in the MMRH group were discharged on the fifth postoperative day, although 80% of them met the criteria to be discharged. We believe that in our country, the main cause is a lack of adequate social or family support. According to a report by the Ministry of Health and Social Services for the Elderly in Spain, 21% of people over the age of 65 years live alone.28 Greater collaboration with discharge care programmes should improve these results. The patient's fear and insecurity about continuing recovery at home could be another cause for discharge delays. Maessen et al.,12 also found delays in hospital discharge among patients who met the discharge criteria. The authors propose better home health care after early discharge. We believe that analysing patient satisfaction after their participation in an MMRH programme might lead to a better understanding of the problem.

After confirming that our MMRH programme improved our patients’ functional recovery, we evaluated the programme's impact on hospital costs. This is a very important point because there is a growing need to improve economic efficiency in perioperative care without compromising results.29 We found a reduction of nearly 1000 euros per patient in total costs in the MMRH group compared with the control group. The main factor contributing to this statistically significant difference was the reduction in the costs associated with the hospitalisation unit. This result is consistent with the decline we have observed in the three-day hospital stay in the MMRH group. This cost reduction was also described by the group at the Cleveland Clinic after they initiated a clinical pathway for postoperative care after ileoanal reservoir surgery.15 In that study, the direct costs and complications were analysed for the first 30 postoperative days and longer term. The patients who were treated according to a MMRH protocol were matched with controls who received conventional care from a different group of surgeons. The major complication rates were comparable, and there were no differences in the rates of readmission or reoperation. The patients in the MMRH group had a shorter hospital stay, and the median direct cost per patient within 30 days was almost 1000 USD less than that of patients receiving traditional care, mainly because of a decrease in the costs of anaesthesia, nursing care, lab tests and other services such as respiratory therapy, stoma management education and nutrition services. In the present study, the decrease in costs was not only related to the Hospitalisation Unit; laboratory costs were also significantly lower in the MMRH group. The costs per patient in radiology and pharmacy were lower, but the difference was not statistically significant. Another economic benefit that should be expected by the institution is greater availability of beds. The reduction in hospital costs even with a low level of compliance with the protocol indicates that, at present, resource utilisation and the costs of perioperative care are far from optimal in most institutions. As highlighted in the meta-analysis by Adamina et al.,30 MMRH programmes optimise resources while accelerating the recovery of patients, thus reducing hospital stay. Additionally, the results of the LAFA3 study31 move in the same direction. LAFA3 is the first randomised, prospective four-cohort study conducted in nine centres in the Netherlands to show that the combination of laparoscopic surgery with perioperative MMRH care leads to faster recovery compared with other treatment combinations. This combination is able to reduce costs primarily by reducing hospital stay, although this cost reduction was not statistically significant. Therefore, these programmes should be used routinely for colorectal surgery. Such routine use is especially important in times of serious economic difficulties, as is currently the case. In this regard, further studies specifically designed to investigate how to minimise costs will provide additional information that may be useful for making treatment choices and investment strategies in hospitals, as was the case of the TAPAS study, a three-cohort prospective study conducted in five Dutch hospitals.32

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the use of a MMRH protocol for elective colorectal surgery reduces both hospital stay and costs without increasing postoperative morbidity or the percentage of readmissions.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Salvans S, Gil-Egea MJ, Pera M, Lorente L, Cots F, Pascual M, et al. Impacto de un programa de rehabilitación multimodal en cirugía electiva colorrectal sobre los costes hospitalarios. Cir Esp. 2013;91:638–644.

Presented at the XIII National Meeting of the Spanish Association of Coloproctology (Barcelona, 27–29 May 2009) and the XXVII National Meeting of Surgery (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 21–24 October 2009).