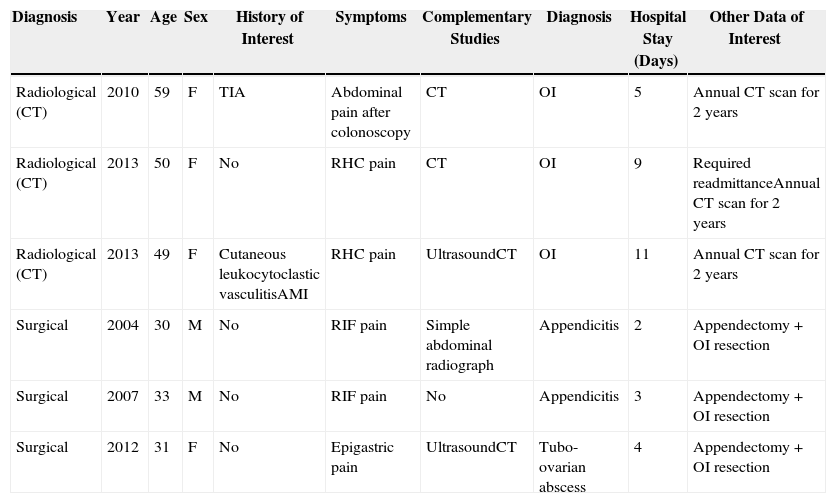

Omental infarction (OI) is a rare cause of acute abdomen.1 The inclusion of the latest radiological advances in standard clinical practice leads one to question the classical surgical management of this disease.2 We present a review of patients who were hospitalized with OI at our hospital in the last 10 years (6 cases) (Table 1), 3 of whom were treated surgically.

Description of the Patients Diagnosed with Omental Infarction at Our Hospital (Period 2003–2013).

| Diagnosis | Year | Age | Sex | History of Interest | Symptoms | Complementary Studies | Diagnosis | Hospital Stay (Days) | Other Data of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiological (CT) | 2010 | 59 | F | TIA | Abdominal pain after colonoscopy | CT | OI | 5 | Annual CT scan for 2 years |

| Radiological (CT) | 2013 | 50 | F | No | RHC pain | CT | OI | 9 | Required readmittanceAnnual CT scan for 2 years |

| Radiological (CT) | 2013 | 49 | F | Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitisAMI | RHC pain | UltrasoundCT | OI | 11 | Annual CT scan for 2 years |

| Surgical | 2004 | 30 | M | No | RIF pain | Simple abdominal radiograph | Appendicitis | 2 | Appendectomy+OI resection |

| Surgical | 2007 | 33 | M | No | RIF pain | No | Appendicitis | 3 | Appendectomy+OI resection |

| Surgical | 2012 | 31 | F | No | Epigastric pain | UltrasoundCT | Tubo-ovarian abscess | 4 | Appendectomy+OI resection |

TIA, transient ischaemic attack; RIF, right iliac fossa; RHC, right hypochondrium; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; OI, omental infarction; F, female; CT, computed tomography; M, male.

The patients who were treated conservatively were diagnosed with OI by computed tomography (CT), with no pathology diagnosis. One patient was readmitted 1 week after discharge due to worsened clinical condition, which required another CT scan and colonoscopy to rule out an underlying disease. All patients received analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antibiotic treatment, which has also been proposed by other authors,1,2 although antibiotic treatment has been disputed in other cases.3,4 After clinical improvement, patients were discharged from hospital after 5, 9 and 11 days, respectively. Two years later, the patients continue to be asymptomatic and annual follow-up CT scans show reduction of the inflammatory mass3,4 as well as the absence of any other omental lesions.1,5

In the patients who were treated surgically, there was no preoperative diagnosis of OI. In 2 cases, surgery was indicated due to suspicion of acute appendicitis, and in one case due to suspicion of tubo-ovarian abscess. In these 3 cases, the diagnosis of OI was confirmed during surgery. In all patients, the affected omentum was resected along with the appendix in order to avoid future errors in diagnosis.2,5,6 The hospital stays were 2, 4 and 4 days, respectively, and there were no postoperative complications. Patients were seen one month after surgery and were asymptomatic.

According to the classification proposed by Leitner et al., OI are defined as either primary or secondary depending on their pathogenesis.7 They can be secondary to torsion caused by adherences, cysts, tumours or hernias, or thrombotic processes due to hypercoagulation disorder, vascular anomalies or trauma (as in our third case). Cases with no discernible cause are considered primary OI, which is the most frequent aetiology, as seen in 5 of our patients. Predisposing factors include obesity, local trauma, excessive eating or cough.5

Within the nonspecific symptoms, there is a predominance of progressive pain in the right hemiabdomen.2 Our 6 cases debuted with symptoms that were compatible with acute abdomen. In general, nausea, vomiting, anorexia or other gastrointestinal signs are absent. This type of presentation should pose a differential diagnosis with cholecystitis, diverticulitis, epiploic appendagitis, tumours displaying fat content, sclerosing mesenteritis or gynaecological causes and, above all, acute appendicitis.

While ultrasound can guide the diagnosis towards OI, CT scan is the study of choice. When OI is caused by torsion, there is a characteristic pattern of concentric hyper-attenuated linear strands in the fat mass, or “whirl sign”.3,4

Complications of OI include the development of adherences and intraabdominal abscesses,3,4,8 so close monitoring is recommended in the first few days, followed by ultrasound follow-up in the first trimester and annual CT scan for the first 3 years.3,4 Surgical treatment, mainly laparoscopic, is recommendable when radiological findings are nonspecific and there are persisting symptoms. Advantages of the laparoscopic approach include shorter hospital stay and prevention of the complications involved in conservative management, while the disadvantages include the risks of general anaesthesia and those related with the surgical procedure itself.9

Although CT has provided a better diagnosis of this disease and enables us to opt for conservative treatment, the surgical approach is still the best alternative to confirm the diagnosis and, fundamentally, to make a differential diagnosis with acute appendicitis. In our series, the diagnosis of OI in the patients managed with conservative treatment was done with abdominal CT, but even so there were diagnostic uncertainties that prompted prolonged hospitalization. In the cases of surgical treatment, however, the pathology study provided the definitive diagnosis of OI.10

One aspect to keep in mind with regards to surgical treatment is that the patients treated conservatively required radiological follow-up studies for 2 years to rule out complications. Meanwhile, the group that received surgical treatment only required one routine office visit one month after the procedure.

As described in our series, most authors recommend conservative management when given a radiological diagnosis of OI, opting for the laparoscopic approach only in cases with worsening symptoms.1,6

Given our experience in surgical cases and the lack of comparative studies demonstrating significant differences between surgical and conservative management, the laparoscopic approach could be considered the diagnostic and therapeutic tool of choice in patients with radiological diagnosis of OI. Surgical treatment favours quick resolution of symptoms and earlier discharge,8 with a low rate of complications. Surgery also avoids the complications of OI itself or those caused by a delay due to an erroneous diagnosis2,4,6,8 and requires fewer complementary studies as well as shorter patient follow-up.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Fuentes PA, López López V, Febrero Sánchez B, Ramírez Romero P, Parrilla Paricio P. Infarto omental: ¿manejo quirúrgico o conservador? Cir Esp. 2015;93:469–471.