Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a rare disease. First described in 1730 by Du Vernoy, it has been defined as the presence of gas within the submucosa or subserosa of the wall of the small intestine and colon, and it has received different names in the literature. The detection of PCI has increased due to the greater use of computed tomography (CT) studies.1 Its clinical presentation can be varied, from accidental findings in asymptomatic patients to life-threatening situations.

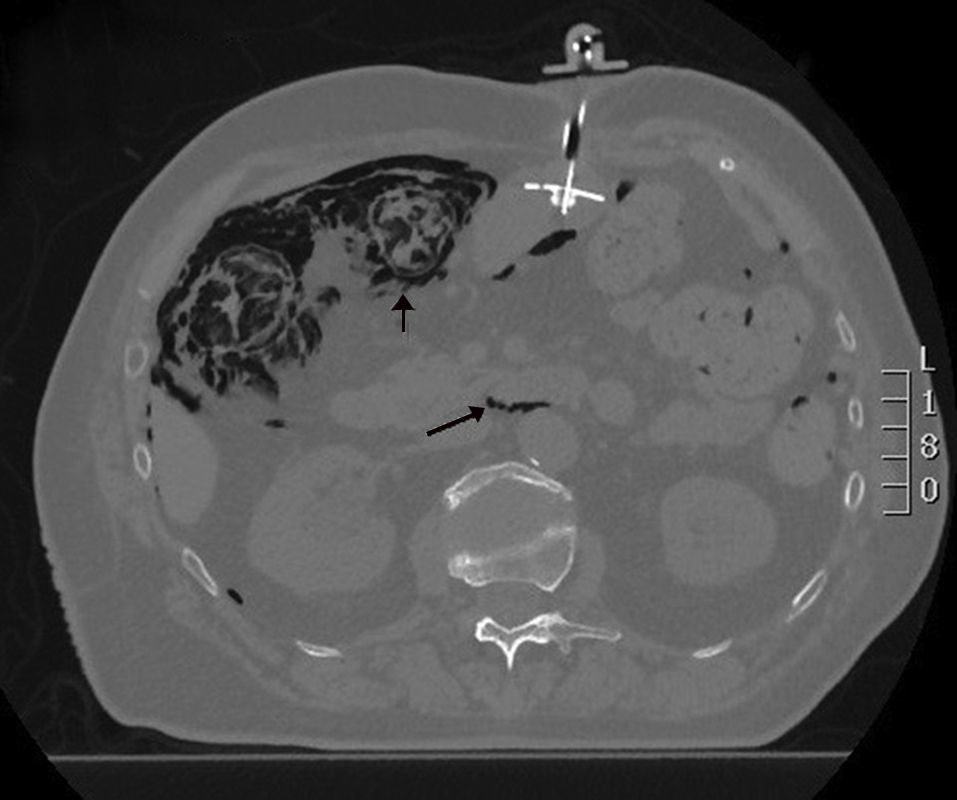

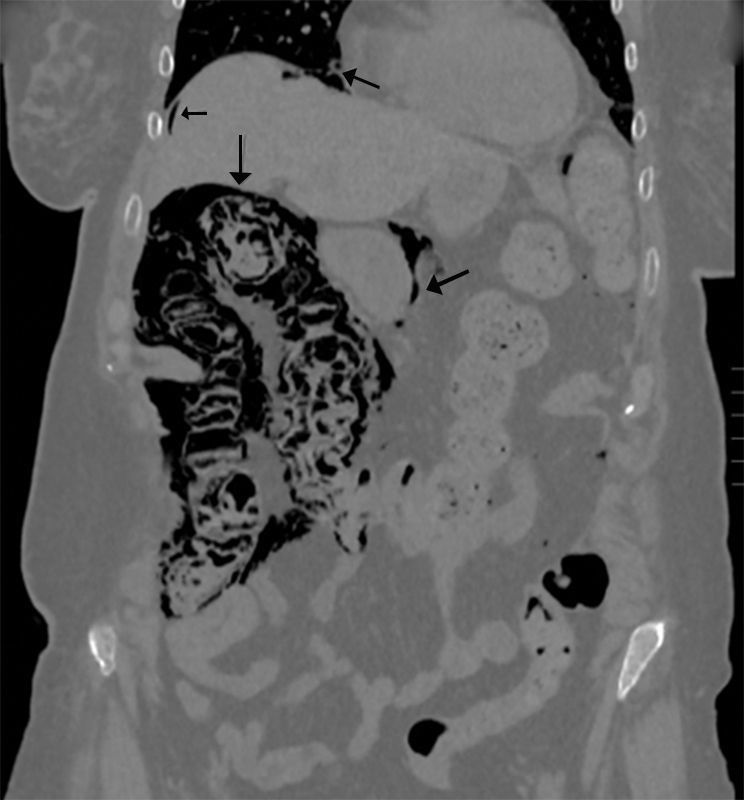

We present the case of a 77-year-old female patient with a history of lacunar stroke with left hemiparesis and Parkinson's disease, associated with multisystemic atrophy and dysphagia, requiring a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) for enteral tube feeding. Two months later, she was evaluated in the outpatient consultation because of abdominal pain and altered bowel transit, with palpation of an abdominal mass in the left iliac fossa and a soft, non-painful abdomen, no peritonism and preserved peristalsis. Lab work was normal. An abdominal Rx was requested, in which the feeding tube and gas were seen in the wall of the right colon, followed by a CT scan that demonstrated the presence of pneumoperitoneum, retropneumoperitoneum and pneumomediastinum; meanwhile, the right colon presented gas in the wall and small parietal air formations in the left and transverse colon, with no mesentery edema or free intra-abdominal fluid. No gas was identified in the vascular structures. The findings described could be compatible with intestinal ischemia, although the patient did not present an acuteabdomen, so it appeared to be a progressive process that could be secondary to PCI (Figs. 1 and 2). We decided to hospitalize the patient for medical treatment with oxygen therapy, antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, fluid therapy and nil per os. The patient progressed favorably, and a control CT showed significant radiological improvement of the pneumatosis intestinalis, with a minimal residual lesion in the hepatic angle of the colon. Stool culture was compatible with dysbiosis. The patient was discharged 14 days later with enteral and oral feeding.

The pathogenesis of PCI is unknown and probably multifactorial. Although older studies show more frequent involvement in the small intestine, more recent studies indicate a greater involvement of the colon.2 This is more common in patients over 50 years of age, idiopathic in 15% and secondary to a wide variety of diseases in 85%, including the association between enteral tube feeding and PCI.3 Disease progression is variable, with a high mortality rate when associated with intestinal necrosis and perforation. Several hypotheses have been suggested in the pathogenesis of PCI, including the mechanical theory in which gas dissects the intestinal wall from its lumen through perforations in the mucosa or through the serous side along the blood vessels.4 The bacterial theory has also been considered, in which the gas produced by the bacteria accesses the submucosa through mucosal lesions.5 The argument against this theory is that the cysts are sterile and their rupture results in pneumoperitoneum with no development of peritonitis.6 The chemical or nutritional deficiency theory argues that malnutrition can impede the digestion of carbohydrates and lead to increased bacterial fermentation in the bowel, with the production of large amounts of gas and, subsequently, dissection of the submucosa by the gas. Recently, PCI has been associated with chemotherapy, hormone therapy and connective tissue diseases.2 Finally, the pulmonary theory postulates that the increased intraluminal pressure in the respiratory system would cause alveolar rupture, so that the gas of the alveoli would dissect the mesenteric vessels through the diaphragm and, hence, the intestinal wall.7

PCI may be asymptomatic, although the most common symptoms are abdominal pain and diarrhea (53%), followed by abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, blood or mucus in stools, and constipation. Almost 16% of patients have complications related with PCI, such as intestinal obstruction, intussusception, volvulus, hemorrhage and perforation.8 The diagnosis of PCI is based on radiology; CT is the most effective imaging method in the detection of pneumatosis, with a cystic pattern along the wall of the intestine.9 Endoscopy is useful to exclude other mucosal lesions and reveal submucosal cysts.8

Appropriate therapy for PCI ranges from conservative treatment to exploratory laparotomy. Asymptomatic patients can be cured without treatment, while symptomatic patients are treated with intestinal decompression, parenteral nutrition and electrolyte replacement. In some cases, response to treatment has been reported with metronidazole and hyperbaric therapy.10 Surgery is reserved for cases of bowel obstruction, perforation or cancer.8

This article is of interest because it presents the diagnosis of a rare disease such as PCI after the placement of a PEG tube as a possible etiological factor. Therefore, this possibility should be contemplated in the differential diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum in an asymptomatic patient with PEG.

Please cite this article as: Barbon Remis E, Garcia Pravia MP, del Campo Ugidos RM, Garcia Álvarez C, Fernández Fernández MC. Neumomediastino y neumoperitoneo secundario a neumatosis quística intestinal tras colocación de gastrostomía endoscópica percutánea. Cir Esp. 2017;95:476–477.