Nowadays, treatment of esophageal cancer requires a multidisciplinary approach, in which esophagectomy remains the mainstay. The aim of this report is to assess whether multimodal treatment and minimally invasive surgery have led to a lower morbidity rate and an improvement in survival rates.

MethodsRetrospective evaluation of 318 patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer including 81 esophagectomies. The periods of 2000–2007 and 2008–2015 were compared, analyzing the prognostic factors that may have an impact in morbidity and survival rate.

ResultsMajor postoperative complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification accounted for 35%, showing a decrease between the 1st and 2nd period: 41% morbidity vs 30%, 27% mortality vs 9% (P<.001) and 13.5% fistulas vs 7%. The implementation of thoracoscopic esophagectomy contributed to the outcome improvement, as shown by 19% morbidity and 5% mortality rates, with triangularized mechanical anastomosis showing 9% fistula and 5% stenosis. The overall 5-year survival rate was 19%, with a significant increase from 11% in the 1st period to 28% in the 2nd (P<.001).

ConclusionsMultidisciplinary assessment of patients with esophageal cancer, as well as better selection and indication of treatment and the introduction of new minimally invasive techniques (thoracoscopy and triangularized mechanical anastomosis), have improved the morbidity and mortality rates of esophagectomies, resulting in increased survival rates of these patients.

Actualmente el tratamiento del cáncer de esófago requiere un enfoque multidisciplinar en el que la esofaguectomía sigue siendo su pilar básico. El objetivo del estudio es analizar si el tratamiento multimodal y la introducción de nuevas técnicas quirúrgicas menos invasivas ha supuesto una disminución de las complicaciones de la esofaguectomía y una mayor supervivencia del cáncer de esófago.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de 318 pacientes con cáncer de esófago que incluyen 81 esofaguectomías. Se comparan los periodos 2000-2007 y 2008-2015 y se analizan los factores pronósticos que pueden influir en las complicaciones y supervivencia.

ResultadosLas complicaciones postoperatorias mayores según la clasificación de Clavien-Dindo fueron globalmente 35%, mostrando una disminución entre el 1.° y 2.° periodo: 41% de morbilidad vs 30%, 27% de mortalidad vs 9% (p < 0,001) y 13,5% de fístulas vs 7%. La incorporación de la esofaguectomía toracoscópica con 19% de complicaciones y 5% de mortalidad y la anastomosis mecánica triangularizada con 5% de fístulas y 9% de estenosis contribuyeron a estos resultados. La supervivencia global a los 5 años fue del 19%, con una mejoría significativa entre el 1.° y 2.° periodo: 11 vs 28% (p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLa valoración multidisciplinar de los pacientes, con una mejor selección e indicación del tratamiento multimodal, y la introducción de nuevas técnicas quirúrgicas menos invasivas y más depuradas, como la toracoscopia y la anastomosis mecánica triangularizada, se ha traducido en una disminución de la morbimortalidad de las esofaguectomías y en un aumento significativo de la supervivencia de los pacientes con CE.

In recent decades, we have witnessed a rapid increase in adenocarcinoma (ADC) of the distal esophagus with a decrease in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the mid-esophagus in western countries.1 Five-year survival of esophageal cancer (EC) remains low, with a global average2 of 10%–20% and 30% after resection.3 However, due to advances made in multimodal treatment4 and surgical technique,5 current rates have reached 40%–57% in esophagectomies. As part of multimodal therapy, esophagectomy is the basic pillar for the treatment of locoregional EC.2 Nonetheless, there continues to be a high rate of major complications (40%–60%)6,7 and a significant risk of mortality (8%–23%)8 depending on the surgical volume of the hospital, although this has been reduced to <2%9 in highly specialized hospitals.

Given the complexity of EC treatment, the assessment of these patients by a multidisciplinary tumor board (MTB) is very useful for better patient selection and correct indication of multimodal treatment.10,11 The creation of Esophageal-Gastric Surgery Units and the application of less invasive surgical techniques, such as thoracoscopy,12 have been able to reduce the morbidity and mortality of this challenging surgery.

The main objective of this study is to retrospectively analyze patients diagnosed with EC at our hospital in order to determine whether current multimodal treatment, with the application of neoadjuvant therapy and the introduction of new less invasive and more refined surgical techniques, such as thoracoscopy and triangulating stapled anastomosis, have been a benefit to reduce complications and increase survival.

MethodsPatients and MethodsWe conducted a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with squamous EC at our hospital from 2000 to 2015. Twenty-nine patients were excluded from the study due to lack of pathology confirmation, 11 due to lack of CT, and 8 due to follow-up <1 year. The study included a total of 318 patients with adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma of the carcinoma, including Siewert type I.

Esophagectomy was performed in 89 patients. In order to establish homogeneous groups with similar postoperative risks and a minimum number of patients, excluded from the study were 4 gastrectomies with distal esophagectomy (whose risk of complications is similar to total gastrectomy and not esophagectomy), 2 esophagectomies performed in two operations and without reconstruction due to early cancer recurrence, and 2 esophagectomies using left thoracotomy. Thus, 81 patients remained with standard esophagectomies for the analysis of complications.

The patients were divided into two 8-year periods, coinciding with the formation in 2008 of the Esophageal-Gastric Surgery Unit and the MTB: 2000–2007 (Period 1) with 157 patients; and 2008–2015 (Period 2) with 161. The observation time was until March 2017, with an average follow-up time of 20 months (0.1–205).

Preoperative characteristics were analyzed, while comorbidity, surgical technique, complications and survival were studied in detail. For the study of possible prognostic factors for complications and survival, the different variables were correlated by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Patient SelectionAll patients underwent barium swallow testing, endoscopy, biopsy, CT scan and, since 2008, endoscopic ultrasound. If the CT was inconclusive, PET was ordered; if the tumors were of the middle third, bronchoscopy was used.

Since 2008, the MTB have evaluated all cases of EC. Based on the extension study results (TNM-7th Edition),13 the following approaches were indicated14: “limited disease” (≤T2/N0/M0), indication for direct surgery; “locally advanced disease” (T3–4/y/o/N+, M0), candidate for neoadjuvant therapy and re-evaluation with CT/PET with subsequent esophagectomy; and “metastatic disease” (M1), chemotherapy or support measures. Neoadjuvant therapy for SCC consisted of preoperative chemotherapy, mainly TPF (docetaxel/cisplatin/5-fluorouracil) with concomitant radiotherapy (45–50, 4Gy), followed by esophagectomy 4–6 weeks later; for ADC, perioperative chemotherapy was used (based on a doublet or triplet combination of platinum/fluoropyrimidines/taxanes) with the possibility of postoperative radiotherapy if R1/2 or N+.

Prior to 2008, esophagectomy was performed if there was no preoperative evidence of metastatic disease or involvement of unresectable organs. Adjuvant therapy (similar regimen of doublets or triplets with postoperative radiotherapy) was indicated when the pathological anatomy confirmed a locally advanced stage.

Surgical TechniqueThe procedures were performed by two surgeons of the unit, currently G.M. and M.V. The standard esophagectomy techniques used were: right transthoracic (Ivor-Lewis), tri-incisional (McKeown), transhiatal (Orringer) and, in recent years, hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy (hybrid MIE)15 using right thoracoscopy in prone position, laparotomy and cervicotomy. The lymphadenectomy performed in the transthoracic and thoracoscopic esophagectomy was standard two-field, and in the transhiatal it was considered incomplete in the thoracic region.

Narrow gastroplasty with pyloroplasty were usually performed, except for 4 coloplasties in patients whose stomach could not be used. The anastomosis at the mediastinum was supra-azygos, with circular mechanical suture (end-to-side). In the cervical region, various techniques were used, generally mechanical. Currently, the standard anastomosis we use is the totally mechanical triangulating method (end-to-side) by Singh,16 which we performed with an endostapler (60×3.5) by means of a suture on the posterior side and two cross-linked sutures on the anterior side. A feeding jejunostomy was routinely created.

DefinitionsComorbidity is expressed by the Charlson comorbidity index, adjusted for age17 (CCI+A) and slightly modified,18 excluding EC itself and metastases from the comorbidities, and accepting for a score: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral vascular, cerebrovascular, chronic pulmonary, connective tissue or benign liver disease, peptic ulcer, diabetes without organ involvement, and dementia=1; hemiplegia, moderate/severe renal disease, diabetes with organ involvement, other active cancers=2; moderate/severe liver disease=3; AIDS=6; <50 years=0; 50–59=1; 60–69=2; 70–79=3; 80–89=4; ≥90=5. The CCI+A was divided into three grades19: low (0–2), medium (3–4) and high (≥5) risk.

Postoperative complications are described according to the Clavien–Dindo classification,20 considering major the following degrees21: III (endoscopic, radiological or surgical intervention with/without general anesthesia), IV (ICU admission due to single/multiple organ failure) and V (death), and also by the international consensus classification by Low.22,23 Both morbidity and mortality were considered during the total post-operative period (in-hospital), even if there was re-admission shortly after discharge (90 days). The survival studied was cancer-specific, assessing the period of time from diagnosis until death of the patient that was esophageal cancer-related. For patients who died from other causes that were not related to esophageal cancer, their follow-up observations until exiting the study were taken into consideration.

Statistical StudyFor the descriptive analysis of the qualitative variables, we used the number and percentage, and for the quantitative variables the mean, standard deviation and range. The study of the prognostic factors of the complications was carried out by means of a univariate analysis for hypothesis contrast with the Chi-square test, and the variables with a significant tendency were analyzed according to a multivariate logistic regression model, adjusted by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, to determine the independent contribution of each. Survival was calculated according to the Kaplan–Meyer method, conducting the univariate analysis with the Log-Rank test and the multivariate analysis using Cox regression.

The statistically significant P-value as well as the confidence interval of the odds ratio was 95% (P<.05). The analysis of the data was done with the SPSS for Windows version 21.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

ResultsOut of the 318 patients, 294 (92.5%) were men and 24 (7.5%) women, with an average age of 65 years (34–87) and no significant differences in either period. The majority were SCC, 228 (71.8%), 80 adenocarcinomas (25.2%) and 10 undifferentiated carcinomas (3.1%). There was a non-significant increase (P=.507) of adenocarcinomas in Period 2: 45 patients (28%) compared to 35 (22.3%) in Period 1. The locations were 23 cervical (7.2%), 32 upper thoracic third (10.1%), 130 mid-thoracic third (40.9%), 127 lower third (39.9%) and 6 multicentric (1.9%). In Period 2, the location in the lower third increased to 68 patients (42.2%), compared to 59 (37.6%) in Period 1, with no significant value. Barrett's esophagus had a lower incidence in Period 2, with 18 (11.2%), compared to 28 (17.8%) in Period 1.

Staging was clinical (cTNM) in 225 patients who were not resected, pathological (pTNM) in 76 who were resected without prior neoadjuvant therapy and pre-neoadjuvant clinical (cTNM) in 17 patients who underwent esophagectomy after neoadjuvant therapy, because it more precisely reflects the advanced nature of the disease than the post-neoadjuvant pathological (ypTNM). The distribution by stages was as follows: Stage 0, 2 patients (0.6%); Stage I, 29 (9.1%); Stage II, 28 (8.8%); Stage III, 172 (54.1%); and Stage IV, 87 (27.4%). There were no significant differences in either period (P=.373).

The tumor was resected in 93 patients (29.2%): 4 endoscopically and 89 by total or partial esophagectomy. The tumor was not resected in 179 cases (56.3%), but these patients were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy with different therapeutic intentions. The tumors of 46 patients (14.5%) were not resected, and these individuals only received supportive care.

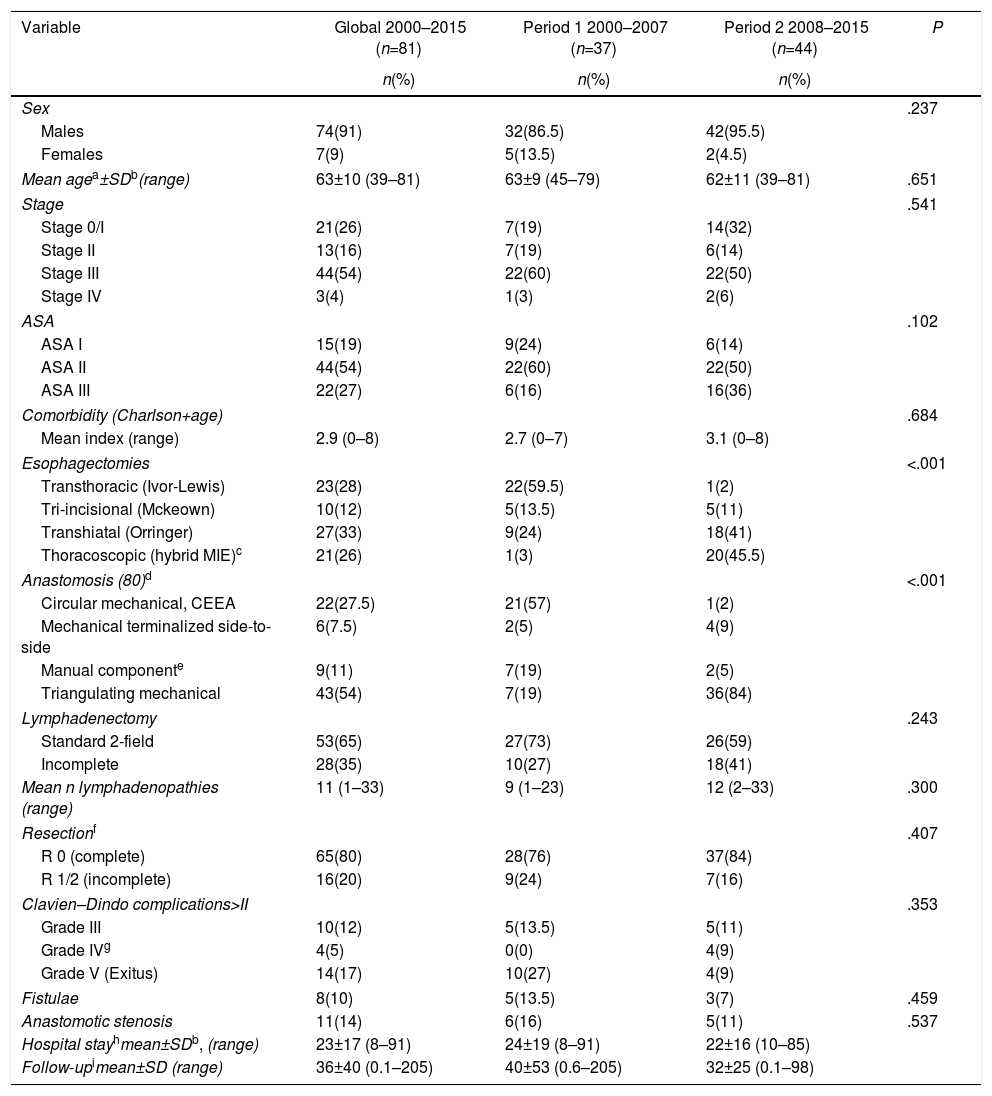

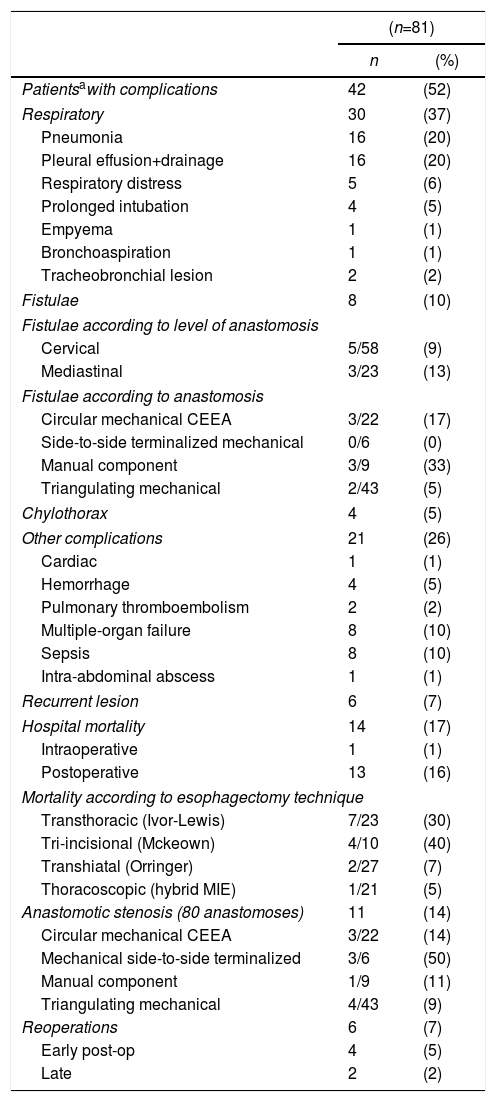

The characteristics of the 81 standard esophagectomies and the major complications of the Clavien–Dindo classification are shown in Table 1. In Period 2, more transhiatal esophagectomies were performed (and, consequently, more incomplete lymphadenectomies) in an attempt to avoid the serious complications of transthoracic esophagectomy, as the introduction of the thoracoscopic approach was progressive. Table 2 demonstrates the complications according to the standardized Low classification. Out of the 8 anastomotic leaks (10%), 7 were type II fistulae, with no need for surgical treatment; the remaining one was due to a necrosis of the plasty (type III), treated by resection and esophageal exclusion, despite which the patient died a few days after the reoperation. Fourteen patients (17%) died as a result of the intervention: one intraoperatively, due to intractable bleeding during transhiatal esophagectomy, and 13 (16%) in the immediate postoperative period. Six patients (7%) were re-operated, 4 of them due to acute complications: one aforementioned necrosis of the plasty, one tracheal fistula treated with pleuroplasty, one chylothorax (type IIIB) with ligation of the thoracic duct and one abdominal abscess with drainage. Two patients were re-operated later due to bowel obstruction and eventration. There were 6 recurrent lesions (7%), all of them transient type I with no need for ENT surgery, and 11 anastomotic stenoses (14%) requiring several endoscopic dilatations.

Esophagectomies: Characteristics and Complications (Clavien–Dindo>II).

| Variable | Global 2000–2015 (n=81) | Period 1 2000–2007 (n=37) | Period 2 2008–2015 (n=44) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | ||

| Sex | .237 | |||

| Males | 74(91) | 32(86.5) | 42(95.5) | |

| Females | 7(9) | 5(13.5) | 2(4.5) | |

| Mean agea±SDb(range) | 63±10 (39–81) | 63±9 (45–79) | 62±11 (39–81) | .651 |

| Stage | .541 | |||

| Stage 0/I | 21(26) | 7(19) | 14(32) | |

| Stage II | 13(16) | 7(19) | 6(14) | |

| Stage III | 44(54) | 22(60) | 22(50) | |

| Stage IV | 3(4) | 1(3) | 2(6) | |

| ASA | .102 | |||

| ASA I | 15(19) | 9(24) | 6(14) | |

| ASA II | 44(54) | 22(60) | 22(50) | |

| ASA III | 22(27) | 6(16) | 16(36) | |

| Comorbidity (Charlson+age) | .684 | |||

| Mean index (range) | 2.9 (0–8) | 2.7 (0–7) | 3.1 (0–8) | |

| Esophagectomies | <.001 | |||

| Transthoracic (Ivor-Lewis) | 23(28) | 22(59.5) | 1(2) | |

| Tri-incisional (Mckeown) | 10(12) | 5(13.5) | 5(11) | |

| Transhiatal (Orringer) | 27(33) | 9(24) | 18(41) | |

| Thoracoscopic (hybrid MIE)c | 21(26) | 1(3) | 20(45.5) | |

| Anastomosis (80)d | <.001 | |||

| Circular mechanical, CEEA | 22(27.5) | 21(57) | 1(2) | |

| Mechanical terminalized side-to-side | 6(7.5) | 2(5) | 4(9) | |

| Manual componente | 9(11) | 7(19) | 2(5) | |

| Triangulating mechanical | 43(54) | 7(19) | 36(84) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | .243 | |||

| Standard 2-field | 53(65) | 27(73) | 26(59) | |

| Incomplete | 28(35) | 10(27) | 18(41) | |

| Mean n lymphadenopathies (range) | 11 (1–33) | 9 (1–23) | 12 (2–33) | .300 |

| Resectionf | .407 | |||

| R 0 (complete) | 65(80) | 28(76) | 37(84) | |

| R 1/2 (incomplete) | 16(20) | 9(24) | 7(16) | |

| Clavien–Dindo complications>II | .353 | |||

| Grade III | 10(12) | 5(13.5) | 5(11) | |

| Grade IVg | 4(5) | 0(0) | 4(9) | |

| Grade V (Exitus) | 14(17) | 10(27) | 4(9) | |

| Fistulae | 8(10) | 5(13.5) | 3(7) | .459 |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 11(14) | 6(16) | 5(11) | .537 |

| Hospital stayhmean±SDb, (range) | 23±17 (8–91) | 24±19 (8–91) | 22±16 (10–85) | |

| Follow-upimean±SD (range) | 36±40 (0.1–205) | 40±53 (0.6–205) | 32±25 (0.1–98) | |

Complications of Esophagectomies According to the Low Classification.

| (n=81) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Patientsawith complications | 42 | (52) |

| Respiratory | 30 | (37) |

| Pneumonia | 16 | (20) |

| Pleural effusion+drainage | 16 | (20) |

| Respiratory distress | 5 | (6) |

| Prolonged intubation | 4 | (5) |

| Empyema | 1 | (1) |

| Bronchoaspiration | 1 | (1) |

| Tracheobronchial lesion | 2 | (2) |

| Fistulae | 8 | (10) |

| Fistulae according to level of anastomosis | ||

| Cervical | 5/58 | (9) |

| Mediastinal | 3/23 | (13) |

| Fistulae according to anastomosis | ||

| Circular mechanical CEEA | 3/22 | (17) |

| Side-to-side terminalized mechanical | 0/6 | (0) |

| Manual component | 3/9 | (33) |

| Triangulating mechanical | 2/43 | (5) |

| Chylothorax | 4 | (5) |

| Other complications | 21 | (26) |

| Cardiac | 1 | (1) |

| Hemorrhage | 4 | (5) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 2 | (2) |

| Multiple-organ failure | 8 | (10) |

| Sepsis | 8 | (10) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 | (1) |

| Recurrent lesion | 6 | (7) |

| Hospital mortality | 14 | (17) |

| Intraoperative | 1 | (1) |

| Postoperative | 13 | (16) |

| Mortality according to esophagectomy technique | ||

| Transthoracic (Ivor-Lewis) | 7/23 | (30) |

| Tri-incisional (Mckeown) | 4/10 | (40) |

| Transhiatal (Orringer) | 2/27 | (7) |

| Thoracoscopic (hybrid MIE) | 1/21 | (5) |

| Anastomotic stenosis (80 anastomoses) | 11 | (14) |

| Circular mechanical CEEA | 3/22 | (14) |

| Mechanical side-to-side terminalized | 3/6 | (50) |

| Manual component | 1/9 | (11) |

| Triangulating mechanical | 4/43 | (9) |

| Reoperations | 6 | (7) |

| Early post-op | 4 | (5) |

| Late | 2 | (2) |

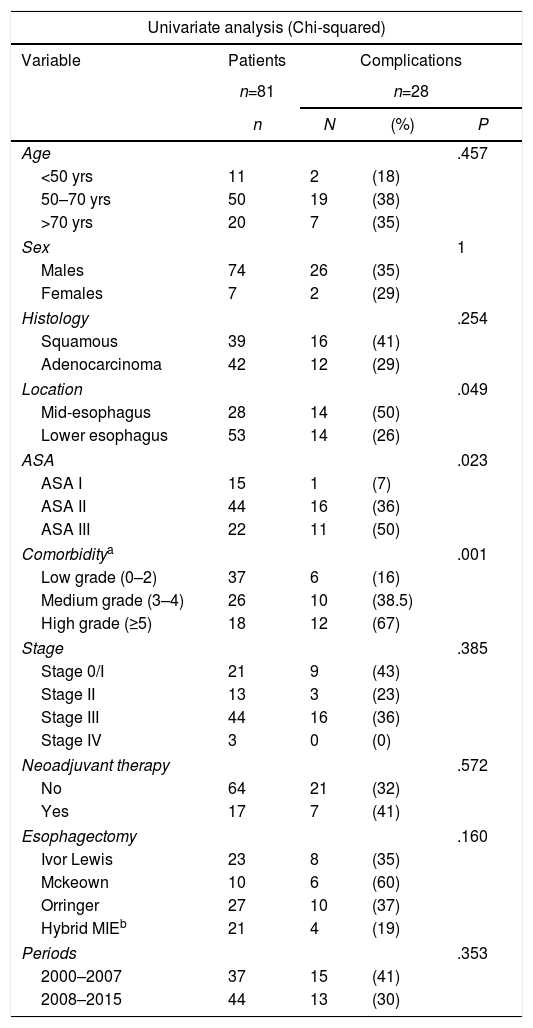

The prognostic factors for postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo>II) are described in Table 3. Location and ASA significantly influenced the appearance of complications and comorbidity, expressed by the CCI+A, and had a very high significant value (P<.001), but only location and CCI+A were independent factors to predict complications.

Prognostic Factors for Complications of Esophagectomies (Clavien–Dindo>II).

| Univariate analysis (Chi-squared) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patients | Complications | ||

| n=81 | n=28 | |||

| n | N | (%) | P | |

| Age | .457 | |||

| <50 yrs | 11 | 2 | (18) | |

| 50–70 yrs | 50 | 19 | (38) | |

| >70 yrs | 20 | 7 | (35) | |

| Sex | 1 | |||

| Males | 74 | 26 | (35) | |

| Females | 7 | 2 | (29) | |

| Histology | .254 | |||

| Squamous | 39 | 16 | (41) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 | 12 | (29) | |

| Location | .049 | |||

| Mid-esophagus | 28 | 14 | (50) | |

| Lower esophagus | 53 | 14 | (26) | |

| ASA | .023 | |||

| ASA I | 15 | 1 | (7) | |

| ASA II | 44 | 16 | (36) | |

| ASA III | 22 | 11 | (50) | |

| Comorbiditya | .001 | |||

| Low grade (0–2) | 37 | 6 | (16) | |

| Medium grade (3–4) | 26 | 10 | (38.5) | |

| High grade (≥5) | 18 | 12 | (67) | |

| Stage | .385 | |||

| Stage 0/I | 21 | 9 | (43) | |

| Stage II | 13 | 3 | (23) | |

| Stage III | 44 | 16 | (36) | |

| Stage IV | 3 | 0 | (0) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | .572 | |||

| No | 64 | 21 | (32) | |

| Yes | 17 | 7 | (41) | |

| Esophagectomy | .160 | |||

| Ivor Lewis | 23 | 8 | (35) | |

| Mckeown | 10 | 6 | (60) | |

| Orringer | 27 | 10 | (37) | |

| Hybrid MIEb | 21 | 4 | (19) | |

| Periods | .353 | |||

| 2000–2007 | 37 | 15 | (41) | |

| 2008–2015 | 44 | 13 | (30) | |

| Multivariate analysis (logistic regression) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable predictor | Coefficient beta | Standard deviation | P | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Location | ||||

| Lower esophagus | 1 | |||

| Mid-esophagus | 1.523 | 0.591 | .010 | 4.584 (1.440–14.599) |

| Charlson Index+age | ||||

| Low grade | 1 | |||

| Medium grade | 1.365 | 0.647 | .035 | 3.914 (1.100–13.919) |

| High grade | 2.766 | 0.749 | <.001 | 15.898(3.661–69.039) |

The overall 5-year survival of the 318 patients was 19%, with a mean survival of 41 months. The most influential factor was tumor stage, as it reflected the advanced nature of the disease at the time of diagnosis: Stage 0/I, 72% 5-year survival; Stage II, 35%; Stage III, 18%; and Stage IV, 0% (P<.001). The therapeutic approach adopted, which logically is closely related to the stage, also had a very significant value: the 5-year survival for esophagectomy with curative intention was 54%, local resection (4 cases) 100%, palliative esophagectomy 0%, not resected but oncological treatment with any intention 8.5%, and not resected with only support measures 0% (P<.001). Five-year survival was 11% in Period 1, with a mean survival of 29 months, and 28% and 36 months Period 2, respectively (P<.001).

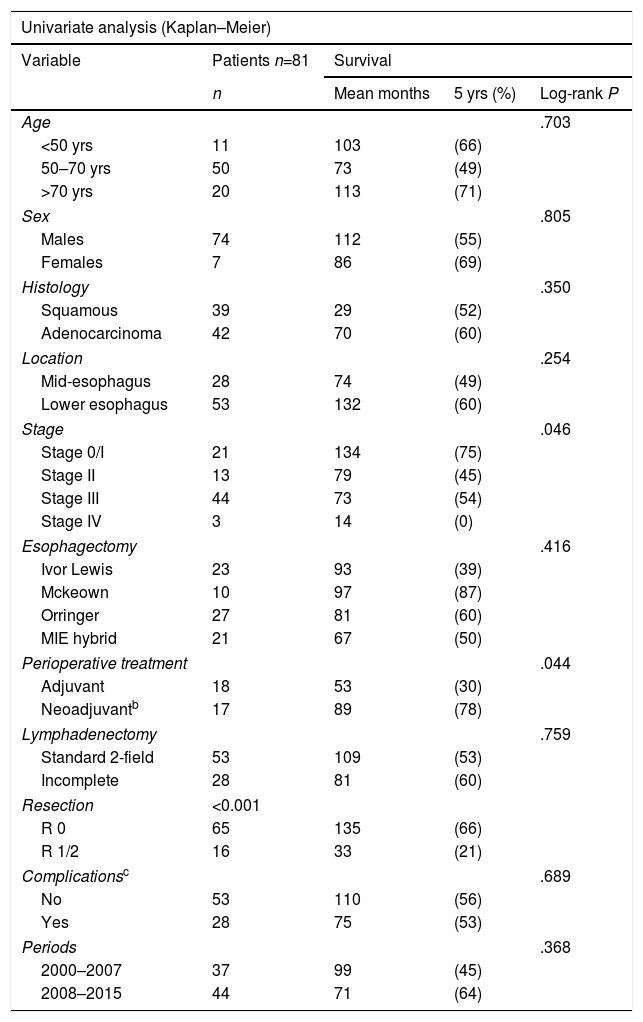

By analyzing the factors that contributed to greater survival in the 81 patients with standard esophagectomies (Table 4), we found that, in addition to stage (P=.046), perioperative oncological treatment was significant (P=.044), especially the type of resection performed (P<.001), which was the only independent factor in the multivariate analysis.

Esophagectomies: Prognostic Factors for Survivala

| Univariate analysis (Kaplan–Meier) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patients n=81 | Survival | ||

| n | Mean months | 5 yrs (%) | Log-rank P | |

| Age | .703 | |||

| <50 yrs | 11 | 103 | (66) | |

| 50–70 yrs | 50 | 73 | (49) | |

| >70 yrs | 20 | 113 | (71) | |

| Sex | .805 | |||

| Males | 74 | 112 | (55) | |

| Females | 7 | 86 | (69) | |

| Histology | .350 | |||

| Squamous | 39 | 29 | (52) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 | 70 | (60) | |

| Location | .254 | |||

| Mid-esophagus | 28 | 74 | (49) | |

| Lower esophagus | 53 | 132 | (60) | |

| Stage | .046 | |||

| Stage 0/I | 21 | 134 | (75) | |

| Stage II | 13 | 79 | (45) | |

| Stage III | 44 | 73 | (54) | |

| Stage IV | 3 | 14 | (0) | |

| Esophagectomy | .416 | |||

| Ivor Lewis | 23 | 93 | (39) | |

| Mckeown | 10 | 97 | (87) | |

| Orringer | 27 | 81 | (60) | |

| MIE hybrid | 21 | 67 | (50) | |

| Perioperative treatment | .044 | |||

| Adjuvant | 18 | 53 | (30) | |

| Neoadjuvantb | 17 | 89 | (78) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | .759 | |||

| Standard 2-field | 53 | 109 | (53) | |

| Incomplete | 28 | 81 | (60) | |

| Resection | <0.001 | |||

| R 0 | 65 | 135 | (66) | |

| R 1/2 | 16 | 33 | (21) | |

| Complicationsc | .689 | |||

| No | 53 | 110 | (56) | |

| Yes | 28 | 75 | (53) | |

| Periods | .368 | |||

| 2000–2007 | 37 | 99 | (45) | |

| 2008–2015 | 44 | 71 | (64) | |

| Multivariate analysis (Cox regression) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variable | Coefficient beta | Standard deviation | P | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| Complete vs incomplete resection | ||||

| R “0” | 1 | |||

| R “1/2” | 1.989 | 0.414 | <.001 | 7.305 (3.246–16.442) |

Prognostic factors related with the probability of dying due to the evolution of esophageal cancer.

The epidemiology of EC is changing in western countries, with an increase in ADC located in the distal esophagus and a decrease in SCC located in the mid-upper esophagus.1 The causes are not well known, but a correlation has been suggested with increased gastroesophageal reflux disease, Barrett's esophagus and obesity.1,2 Our data confirm this progressive trend, reaching 44% distal ADC and 60% distal EC in 2015, but have not been able to associate it with the increased incidence of Barrett's esophagus. The technique and approach of esophagectomies are continuously being debated to try to reduce the complications of this complex surgery. In our country, groups24,25 that advocate the use of minimally invasive esophagectomy have delighted many esophagogastric surgeons by demonstrating that thoracoscopy is a possible and safe approach. Currently, there is a trend favoring intrathoracic anastomosis in distal EC using the Ivor-Lewis technique with MIE,9,26,27 avoiding cervical anastomosis, with the justification that it is not necessary for oncological criteria to resect the entire esophagus, decreasing recurrent lesions and fistulae. This may be true, but in our opinion performing the mediastinal anastomosis by MIE is complex and not without complications. Robotic surgery28 is an alternative, although its availability and the operative time required limit its use. We think that it is fundamental in CE surgery to avoid the serious complications of esophagectomy, due in large part to thoracotomy, and that thoracoscopy has many advantages, especially in reducing respiratory complications,11,24 which are the main cause of death in this surgery.29,30 Abdominal time with the open approach (hybrid MIE) makes it easier to perform a large Kocher maneuver to obtain a gastroplasty long enough to reach the neck, a pyloroplasty and a feeding jejunostomy. Cervical triangulating stapled anastomosis16 has been confirmed as a very safe technique that minimizes the manipulation of the ends used to create the anastomosis, which is the main cause of fistulae due to the precarious vascularization of the plasty, and provides a wide anastomotic surface resulting in few cases of postoperative stenosis.16,31

It is necessary to define the postoperative complications in an objective and comparable manner in order to evaluate the results of the surgery. The morbidity of esophagectomies is usually reported as major complications of the Clavien–Dindo classification.17,21 Following this criterion, out of the 81 esophagectomies analyzed, 28 (35%) had major complications, leading to exitus in 14 (17%). This classification of complications, based on the therapeutic effort necessary to treat them, has been proven useful and objective in retrospective studies, but it does not include all the serious complications that actually occur in esophagectomies; therefore, it must be complemented with the standardized classification by Low.22,23 According to this classification, we had 42 patients (52%) with serious complications, the most frequent of which were respiratory complications (30; 37%) and fistulae (8; 10%). If no invasive treatment measures are required, some may not be considered major complications in the Clavien–Dindo classification, as it actually minimizes the morbidity of an operation as complex as esophagectomy. When studying the factors that can influence the complications of esophagectomies, we found that only the location (P=.049) and comorbidity (P<.001), expressed by the CCI+A, had significant independent values. The correct indication of an esophagectomy in a patient with EC is essential because, although a reduction in mortality has been achieved, morbidity remains very high.6,7,29 For this reason, multiple scales have been developed to assess surgical risk, the most accepted of which is Charlson's age-adjusted scale.32 CCI + A is an objective criterion to consider when indicating esophagectomy,18 and postoperative clinical pathways33 are also very useful.

The surgical technique and approach influenced the complications, although not at a significant level in our study (P=.160): out of the 21 hybrid thoracoscopic esophagectomies, 4 (19%) had major complications and only one (5%) died compared to 35% complications in the Ivor-Lewis study and 60% reported by Mckeow. The type of anastomosis at the cervical level also influenced the appearance of fistulae and stenosis: out of the 43 triangulating mechanical anastomoses, 2 (5%) presented fistulae and 4 (9%) had postoperative stenosis, compared to 33% and 11%, respectively, with the manual technique.

The 5-year overall survival of the 318 patients was 19%, similar to publications by other authors.2 This is evidence of the aggressiveness of EC, which in most cases is detected in advanced stages.2,34 Age, histological type and, logically, the stage and therapeutic approach used significantly influenced survival. However, the period analyzed was also a factor: 28% 5-year survival in Period 2 compared to 11% in Period 1 (P<.001). It is difficult to demonstrate which changes contributed to this improvement, but multidisciplinary assessment and better patient selection for multimodal treatment were among the modifications that had been made.

The factors that significantly influenced the survival after esophagectomy, in addition to the stage, were the perioperative treatment and the type of tumor resection that was performed. Neoadjuvant therapy provided surprisingly good results, with a 78% 5-year survival rate versus 30% with adjuvant therapy (P=.044). We believe that these results, although true, are not valid for comparing adjuvant vs neoadjuvant treatment due to selection bias since several patients, who were initially indicated neoadjuvant therapy, presented disease progression before being able to perform surgery and therefore could not be included in this survival analysis, which includes only esophagectomies. In addition, the follow-up time for patients with neoadjuvant therapy was shorter than the follow-up of patients with adjuvant therapy. There are several patients in the first group with disease recurrence who would probably have died from EC given a longer observation time. Complete tumor resection (R0) reached a 5-year survival rate of 66%, versus 21% in incomplete resections (P<.001), and in the multivariate analysis it was the only independent protective factor. The main benefit of neoadjuvant treatment35 is to achieve a higher rate of complete resections and avoid esophagectomies in patients who were likely to progress anyway.

Currently the real issue to achieve greater survival in EC is not the surgical technique (except as a means to avoid morbidity and mortality), but instead multimodal treatment.36 Chemotherapy37 with specific therapeutic targets (HER2 and EGFR), immunotherapy and radiotherapy with protons,38 increasingly selective and with less damage to the surrounding tissues, are important fields of future research.

The main inconsistencies of our study are due to the fact that it is a retrospective analysis with non-randomized groups, analyzing long periods of time with different treatment regimens and follow-up times. This, as we saw earlier, may give inconclusive results. The general group of 318 patients with EC is not small, but the number of esophagectomies analyzed (81) is, and the subgroups are even smaller. In conclusion, we believe that this study, despite its methodological limitations, may be useful to confirm that the multidisciplinary assessment of patients with EC, with better selection and indication for multimodal treatment, and the introduction of new less invasive, refined surgical techniques, such as thoracoscopy and triangulating mechanical anastomosis, result in reduced esophagectomy morbidity and mortality and in a significant increase in the survival of patients with EC.

Authorship/collaborators- -

Main researcher: G.I. Moral Moral, study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, article composition, critical review and approval of the final version

- -

Secondary researchers: M. Viana Miguel, O. Vidal Doce, R. Martínez Castro, R. Parra López, A. Palomo Luquero, M.J. Cardo Díez, I. Sánchez Pedrique, J. Santos González, J. Zanfaño Palacios: study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, article composition, critical review and approval of the final version.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

- -

Dr. José Cordero Guevara, healthcare technician at the Primary Care Administration in Burgos, Spain (Gerencia de Atención Primaria), for his assistance in the statistical analysis of the study.

- -

Dr. Ana López Muñoz of the Medical Oncology Department and Dr. Eva Corrales García of the Radiotherapeutic Oncology Department, for their continued participation in the Multidisciplinary Digestive Tumor Committee at the Hospital Universitario de Burgos.

- -

Dr. Juan Luís Seco Gil, former Director of the General Surgery Department, for his decisive contribution to the training and development of the Esophagogastric Surgery Unit and the Multidisciplinary Digestive Tumor Committee at the Hospital Universitario de Burgos.

- -

Dr. José L. Elorza Orúe, Dr. José I. Asensio Gallego and Dr. Santiago Larburu Etxaniz of the Hospital de Donostia in San Sebastián for their instruction in thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal cancer.

Please cite this article as: Moral Moral GI, Viana Miguel M, Vidal Doce Ó, Martínez Castro R, Parra López R, Palomo Luquero A, et al. Complicaciones postoperatorias y supervivencia del cáncer de esófago: análisis de dos periodos distintos. Cir Esp. 2018;96:473–481.

Part of the information in this article was presented at the 19th Congress of the Association of Surgeons of Castilla y León, held in Burgos, Spain on June 8–9, 2017.