The general use of techniques like computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging for the follow-up of oncological patients has increased the detection of adrenal masses.1 These lesions are a clinical challenge due to the diagnostic doubts generated about their nature, especially in patients with a history of neoplasms in the lungs, breasts or colon.1,2

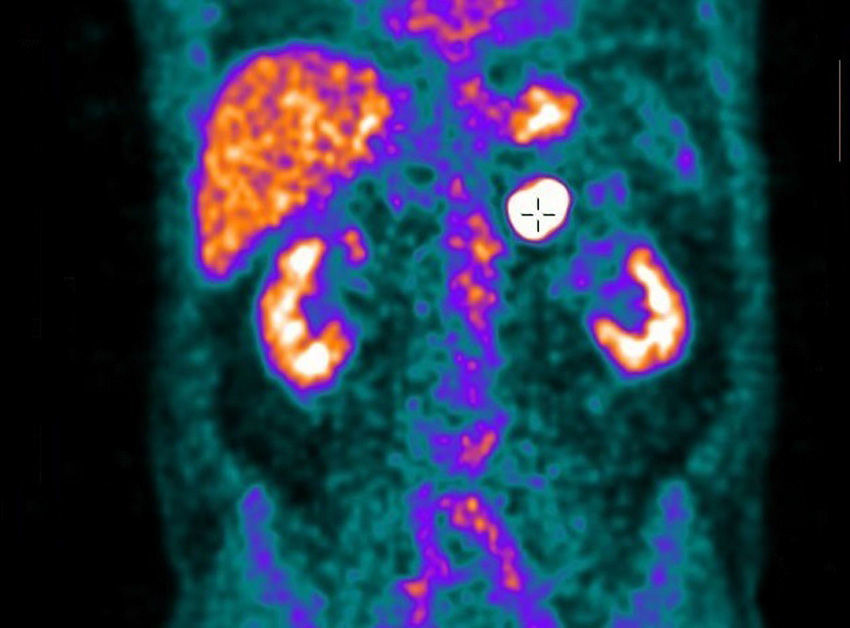

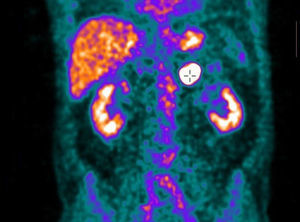

We present the case of a 64-year-old male patient, with no prior medical history of interest, who had been treated surgically one year earlier for adenocarcinoma of the sigma (stage pT3N0M0) and had afterwards received adjuvant chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen. The follow-up CT 9 months after surgery detected the appearance of a new left adrenal lesion. The mass was oval and had moderate attenuation (Fig. 1). Positron emission tomography (PET) presented increased metabolic activity with a maximum SUV of 16.47 (Fig. 2). Given the patient's recent medical history, the initially suspected diagnosis was adrenal metastasis of the colon adenocarcinoma. Because it was a rapidly-growing lesion and appeared to be resectable on the imaging studies, we decided to conduct laparoscopic left adrenalectomy to make a definitive diagnosis. En bloc resection of the lesion was carried out. The histopathologic study reported the presence of infiltration of the suprarenal gland by a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a high cell proliferation rate. The patient received treatment with 6 cycles of a chemotherapy regimen including rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), as well as intrathecal prophylaxis. The patient continues to be disease-free one year later.

Adrenal involvement in the context of disseminated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is uncommon.2,3 Nonetheless, primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) is also an unusual condition.1–3 Extranodal lymphomas located in the gland tissue represent only 3%, and the thyroid is the most frequent location.4,5

The presentation of PAL is generally bilateral,1,6,7 and it is unilateral in less than one-third of cases.2,5 At diagnosis, extra-adrenal involvement is uncommon, although it presents a definite tendency towards extra-nodal dissemination during the course of the disease, especially to the stomach, liver, and central nervous system.4

It is a disease that most frequently affects males in the sixth and seventh decades of life.2,5–7 Its aetiology is unknown.3,4 There are speculations about a possible autoimmune origin secondary to autoimmune adrenalitis, although a haematopoietic origin from embryonic remains has been proposed.4–6 Predisposing factors for the development of the disease that have been identified include a history of immunological dysfunction secondary to neoplasms of other locations and HIV or Epstein–Barr infection.6 Clinical symptoms are variable and not very specific.3 The most frequent are B symptoms (fever, night sweats and weight loss), followed by abdominal or dorsal pain, anorexia, fatigue or clinical data for adrenal insufficiency.5–7

Only 1% of these tumours are diagnosed incidentally on imaging tests.5 The echogenicity of these lesions is variable and no specific pattern has been reported to provide an ultrasound diagnosis.5 On CT, which is currently considered the test of choice in the diagnosis of adrenal masses,3 the lesions are characterised by a general increase in the size of the gland, maintaining its architecture but presenting variable densities.2 It is frequent to find them as low uptake lesions with moderate uptake after the administration of intravenous contrast.5 Areas of necrosis and intraparenchymal haemorrhages may also be observed.3 On MRI, they present as isointense as well as hypointense lesions in T1 and hyperintense in T2.3,5 PET studies always detect increased metabolic activity.3,5

The diagnosis should be confirmed by histology.1,2 Given the suspicion, gland excision or ultrasound/CT-guided core-needle biopsy are the diagnostic tests of choice.4,6 The differential diagnosis should be established with adrenal tuberculosis, haematomas, infections, non-functioning adenomas, phaeochromocytoma, adrenal carcinoma and metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the lungs, breasts, kidneys, pancreas or melanoma.1,4

If the lesion is resectable, the treatment of choice should be surgical excision, which should be complemented with chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy,1,6 although the actual benefit of radiotherapy has not been well established.5 The most frequently used chemotherapy regimen is CHOP with rituximab,6,7 since the most recent studies have demonstrated that the combination of rituximab increases survival.5,7

The prognosis is generally unfavourable.3,4 The best survival rates are observed when the involvement is unilateral1 and when there is a complete response to chemotherapy.5 Surgical resection is a factor for a positive prognosis in most univariate analyses, although it loses its significance in the multivariate analyses.5 Factors for a poor prognosis include advanced age, tumour size, elevated LDH or adrenal insufficiency at the time of diagnosis and bilateral adrenal involvement.2,3,7

In conclusion, adrenal lymphoma is an uncommon condition whose diagnosis is generally reached after the excision of the affected gland. The prognosis is unfavourable, although treatment with immunochemotherapy improves patient prognosis.

FundingNo funding was required to complete this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Sagarra Cebolla E, López Baena JÁ, Carrasco Muñoz S, del Corral Rodriguez J, Lozano Lominchar P. Linfoma adrenal primario; una entidad poco frecuente en el diagnóstico diferencial de las tumoraciones suprarrenales. Cir Esp. 2016;94:607–609.