Median arcuate ligament (MALS) syndrome involves extrinsic compression of the celiac artery by the fibrous bands of the median arcuate ligament (MAL).1 It was first described in 1917 by Lipshutz et al.,1,2,5 but it was not until 1963 when Harjola et al. performed the first surgeries to treat MALS.1,3 In 1972, Colapinto et al. used CT for the first time for the diagnosis of MALS, and since then it has become the best diagnostic method.4

MALS is usually asymptomatic because collateral circulation develops, but in 10%–25% of cases some type of functional ischemia may occur.1 Symptomatic patients may present abdominal pain with no obvious cause, which may be postprandial or triggered by exercise, as well as weight loss, nausea and vomiting.1,5

MALS that is not correctly evaluated or treated can cause serious complications after supramesocolic surgeries, especially pancreaticoduodenectomy.7 However, the number of publications on patients with MALS undergoing liver transplantation (LT) is very limited, and no internationally accepted recommendations have been published about the best therapeutic strategy to follow.1 It has been suggested that MALS can cause postoperative dysfunction of the liver graft by decreasing the mean flow velocity of the hepatic artery, thereby hindering flow to the graft, which can lead to hepatic artery thrombosis and biliary complications.5 We present our experience in the synchronous treatment of MALS and LT.

Using a prospective database, we have conducted a retrospective observational study of all patients who had undergone LT from September 2012 to December 2021. Patients with preoperative CT scan diagnosis of MALS were selected (Fig. 1). We performed a temporary portacaval shunt and divided the MAL after completing total hepatectomy.

Within 24 h of LT, Doppler ultrasound was used to confirm the permeability of the arterial flow. The following clinical variables were studied: preoperative (age, sex, etiology of liver disease, MELD, preoperative hemoglobin, and donor risk index [DRI]); intraoperative (cold ischemia time, blood loss, arterial and portal flow pre/post-transplantation, and operative time); and postoperative (complications defined by Clavien-Dindo classification,8 especially vascular, hospital stay, graft and patient survival).

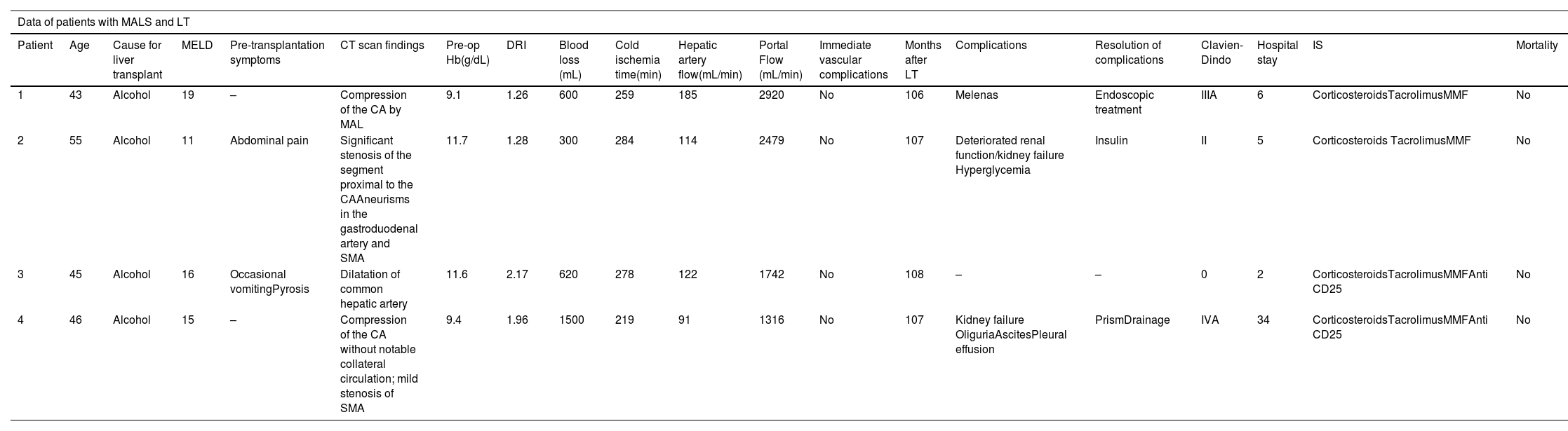

We have operated on 4 patients with MALS, representing an incidence in our series of 1.01% (4/394). There were no complications associated with the division of the MAL. All grafts presented good perfusion after performing the venous and arterial anastomoses, and no post-transplantation vascular or biliary complications were observed. Vascular grafts were not used in any of these patients. Patient data are summarized in Table 1A. The published series on LT and MALS that we reviewed are presented in Table 1B.

Characteristics of the patients treated.

| Data of patients with MALS and LT | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age | Cause for liver transplant | MELD | Pre-transplantation symptoms | CT scan findings | Pre-op Hb(g/dL) | DRI | Blood loss (mL) | Cold ischemia time(min) | Hepatic artery flow(mL/min) | Portal Flow (mL/min) | Immediate vascular complications | Months after LT | Complications | Resolution of complications | Clavien-Dindo | Hospital stay | IS | Mortality |

| 1 | 43 | Alcohol | 19 | – | Compression of the CA by MAL | 9.1 | 1.26 | 600 | 259 | 185 | 2920 | No | 106 | Melenas | Endoscopic treatment | IIIA | 6 | CorticosteroidsTacrolimusMMF | No |

| 2 | 55 | Alcohol | 11 | Abdominal pain | Significant stenosis of the segment proximal to the CAAneurisms in the gastroduodenal artery and SMA | 11.7 | 1.28 | 300 | 284 | 114 | 2479 | No | 107 | Deteriorated renal function/kidney failure Hyperglycemia | Insulin | II | 5 | Corticosteroids TacrolimusMMF | No |

| 3 | 45 | Alcohol | 16 | Occasional vomitingPyrosis | Dilatation of common hepatic artery | 11.6 | 2.17 | 620 | 278 | 122 | 1742 | No | 108 | – | – | 0 | 2 | CorticosteroidsTacrolimusMMFAnti CD25 | No |

| 4 | 46 | Alcohol | 15 | – | Compression of the CA without notable collateral circulation; mild stenosis of SMA | 9.4 | 1.96 | 1500 | 219 | 91 | 1316 | No | 107 | Kidney failure OliguriaAscitesPleural effusion | PrismDrainage | IVA | 34 | CorticosteroidsTacrolimusMMFAnti CD25 | No |

CT: computed tomography. CA: celiac artery. MAL: median arcuate ligament. SMA: superior mesenteric artery. Hb: hemoglobin. DRI: donor risk index. cc: cubic centimeters. LT: liver transplantation.

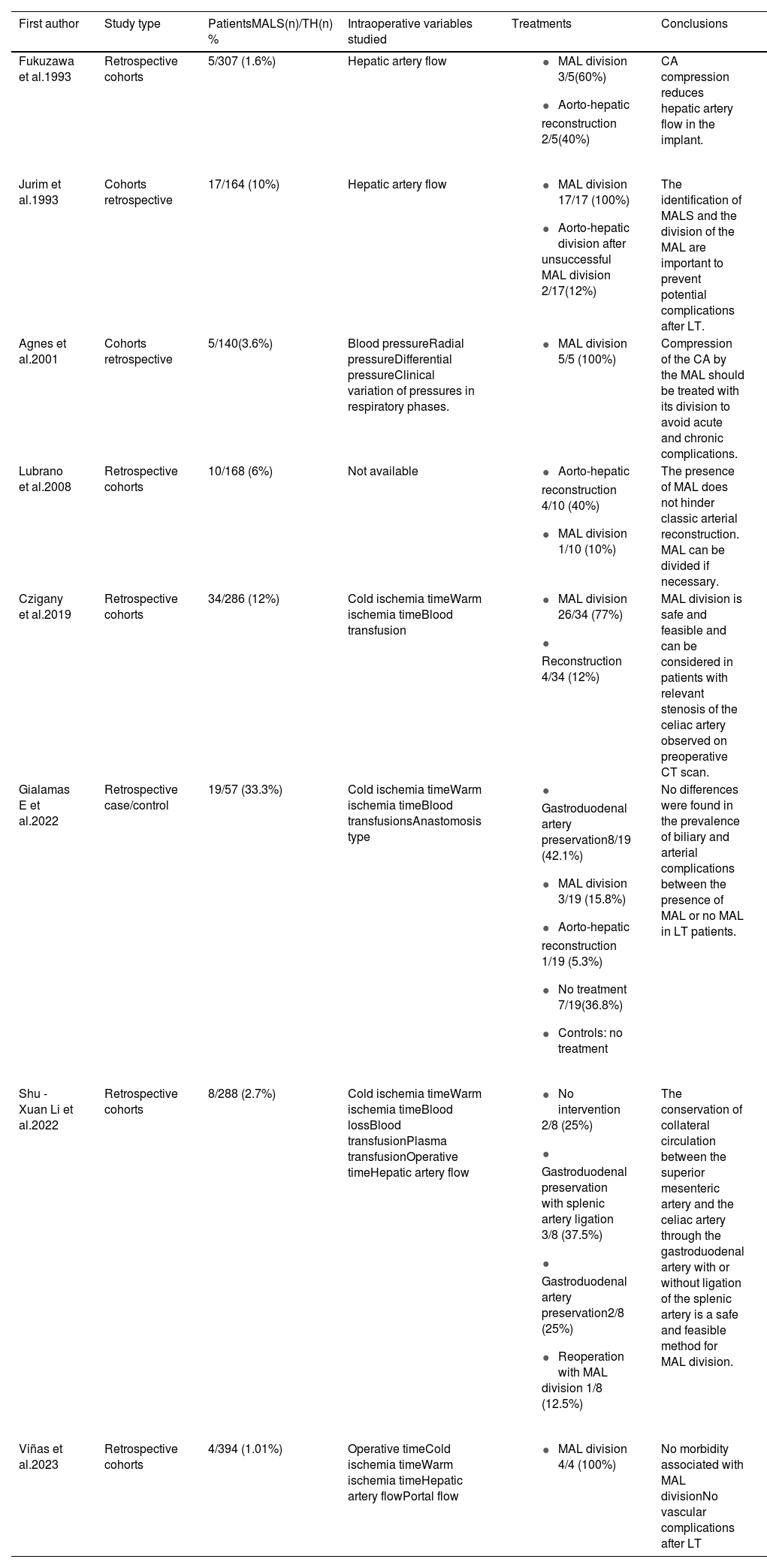

Published series.

| First author | Study type | PatientsMALS(n)/TH(n) % | Intraoperative variables studied | Treatments | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fukuzawa et al.1993 | Retrospective cohorts | 5/307 (1.6%) | Hepatic artery flow |

| CA compression reduces hepatic artery flow in the implant. |

| Jurim et al.1993 | Cohorts retrospective | 17/164 (10%) | Hepatic artery flow |

| The identification of MALS and the division of the MAL are important to prevent potential complications after LT. |

| Agnes et al.2001 | Cohorts retrospective | 5/140(3.6%) | Blood pressureRadial pressureDifferential pressureClinical variation of pressures in respiratory phases. |

| Compression of the CA by the MAL should be treated with its division to avoid acute and chronic complications. |

| Lubrano et al.2008 | Retrospective cohorts | 10/168 (6%) | Not available |

| The presence of MAL does not hinder classic arterial reconstruction. MAL can be divided if necessary. |

| Czigany et al.2019 | Retrospective cohorts | 34/286 (12%) | Cold ischemia timeWarm ischemia timeBlood transfusion |

| MAL division is safe and feasible and can be considered in patients with relevant stenosis of the celiac artery observed on preoperative CT scan. |

| Gialamas E et al.2022 | Retrospective case/control | 19/57 (33.3%) | Cold ischemia timeWarm ischemia timeBlood transfusionsAnastomosis type |

| No differences were found in the prevalence of biliary and arterial complications between the presence of MAL or no MAL in LT patients. |

| Shu -Xuan Li et al.2022 | Retrospective cohorts | 8/288 (2.7%) | Cold ischemia timeWarm ischemia timeBlood lossBlood transfusionPlasma transfusionOperative timeHepatic artery flow |

| The conservation of collateral circulation between the superior mesenteric artery and the celiac artery through the gastroduodenal artery with or without ligation of the splenic artery is a safe and feasible method for MAL division. |

| Viñas et al.2023 | Retrospective cohorts | 4/394 (1.01%) | Operative timeCold ischemia timeWarm ischemia timeHepatic artery flowPortal flow |

| No morbidity associated with MAL divisionNo vascular complications after LT |

MALS: median arcuate ligament syndrome. LT: liver transplant. MAL: median arcuate ligament. CA: celiac artery. CD: Clavien Dindo. CCI: comprehensive complications index.

MALS is an uncommon condition in the general population. According to published series,5 the reported incidence in post-LT patients ranges from 1.6%–33%, although our series had a slightly lower incidence (1%). The symptoms of MALS are non-specific; 2 of our patients presented abdominal pain, which was accompanied by vomiting in one case. The usual symptoms of MALS can be attributed to chronic liver disease.10 Therefore, its diagnosis is difficult and requires thorough radiological evaluation of the pre-transplantation CT scan, thus allowing the surgeon to establish an appropriate intraoperative surgical strategy.1,5,9,10

To date, there are no established treatment recommendations for MALS in patients undergoing LT.1,5 There is a classification of MALS in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, and the treatment is adapted according to the percentage and length of the stenosis.10 However, it has not been determined whether this algorithm is applicable in LT. Surgical treatment is generally accepted as being required in symptomatic patients, but there is no consensus on treatment in cases with no obvious symptoms.1,5,9,10 Advocates of treating any MALS in patients undergoing LT argue that, if left untreated, the risk of post-LT vascular and biliary complications may increase, while treatment does not increase morbidity.1 Nevertheless, the few published series provide no data confirming a higher incidence of vascular and biliary complications after LT if there is asymptomatic MALS that is not treated.1,6

When treating MALS in patients undergoing LT, therapeutic options include: division of the MAL, preservation of the gastroduodenal artery, or more complex techniques, such as aorto-hepatic bypass or endovascular techniques.5,6,9,10 In our series, we performed division of the MAL in all cases, and no morbidity was observed associated with this technique. One of the possible complications indicated associated with the division of the MAL is that hemorrhage occurs due to the existence of varices and abundant collateral circulation in the area. We believe that the portacaval shunt that we perform in all of our patients minimizes this risk, facilitating division of the MAL.

In conclusion, MALS in patients undergoing LT is rare, usually asymptomatic, and requires a thorough pre-transplantation CT study. There are no therapeutic algorithms with high scientific evidence, but since its treatment does not increase morbidity, we believe that MAL division is advisable to avoid possible postoperative vascular and/or biliary complications.