To analyze short and medium-term results of different surgical techniques in the treatment of complicated acute diverticulitis (CAD).

MethodsMulticentre retrospective study including patients operated on as surgical emergency or deferred-urgency with the diagnosis of CAD.

ResultsA series of 385 patients: 218 men and 167 women, mean age 64.4±15.6 years, operated on in 10 hospitals were included. The median (25th–75th percentile) time from symptoms to surgery was 48 (24–72)h, being peritonitis the main surgical indication in a 66% of cases. Surgical approach was usually open (95.1%), and the commonest findings, a purulent peritonitis (34.8%) or pericolonic abscess (28.6%). Hartmann procedure (HP) was the most used technique in 278 (72.2%) patients, followed by resection and primary anastomosis (RPA) in 69 (17.9%). The overall postoperative morbidity and mortality was 53.2% and 13% respectively. Age, immunosuppression, presence of general risk factors and fecal peritonitis were associated with increased mortality. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage (LPL) was associated with an increased reoperation rate frequently involving a stoma, and anastomotic leaks presented in 13.7 patients after RPA, without differences in morbimortality when compared with HP. Median postoperative length of stay was 12 days, and was correlated with age, surgical risk, ASA score, hospital and postoperative complications.

ConclusionsSurgery for CAD has important morbidity and mortality and is frequently associated with an end-stoma. Moreover LPL presented high reoperation rates. It seems better to resect and anastomose in most cases, even with an associated protective stoma.

Se pretende analizar los resultados a corto y medio plazo de diferentes técnicas quirúrgicas en el tratamiento de la diverticulitis aguda complicada (DAC).

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo y multicéntrico de pacientes operados de urgencia o de urgencia diferida por DAC.

ResultadosEstudiamos a 385 pacientes: 218 hombres y 167 mujeres, de edad media 64,4±15,6 años, intervenidos en 10 hospitales. La mediana (25-75° percentiles) de evolución desde el inicio de los síntomas hasta la cirugía fue de 48h (24-72), y su indicación más frecuente, un cuadro peritonítico (66%). El abordaje fue generalmente abierto (95,1%) y los hallazgos más comunes, peritonitis purulenta (34,8%) o absceso pericólico (28,6%). La técnica más habitual fue el procedimiento de Hartmann (PHT) en 278 (72,2%), seguida de resección y anastomosis primaria (RAP) en 69 (17,9%). Se complicaron 205 pacientes (53,2%) y fallecieron 50 (13%). Edad avanzada, inmunodepresión, factores de riesgo quirúrgico y peritonitis fecal se asociaron a mayor mortalidad. El lavado peritoneal laparoscópico (LPL) tuvo elevada tasa de reintervenciones, implicando frecuentemente un estoma, y la RAP se complicó con dehiscencia de sutura en el 13,7% de pacientes, sin diferencias en la morbimortalidad al compararla con el PHT. La mediana de estancia postoperatoria fue de 12 días; su mayor duración se relacionó con la mayor edad, riesgo quirúrgico ASA, hospital y complicaciones postoperatorias.

ConclusionesLa cirugía por DAC tiene importante morbimortalidad y se asocia frecuentemente a un estoma terminal. Además, el LPL presenta alta tasa de reintervenciones. LA RAP, aun asociando un estoma de protección, parece de elección en muchos casos.

The surgical management of complicated acute diverticulitis (CAD) is controversial. There is much debate about whether or not to perform anastomoses1–3 and whether to use a minimally invasive approach, such as laparoscopic peritoneal lavage (LPL).3–6

In a previous study, we showed evidence of a low rate of reconstruction of intestinal continuity after the Hartmann procedure (HP),7 which also involves morbidity, mortality and non-negligible costs. Therefore, when determining the therapeutic approach in the emergency room, comparisons should be made between the two procedures versus resection and primary anastomosis (RPA) or the long-term outcomes of non-resective management.8

In our country, there are groups with great experience in the management of CAD,4 but there are no reviews about its standard treatment. The aim of this present study is to analyze the short- and medium-term results of different surgical techniques in the treatment of CAD at different hospitals in the Valencian Community of Spain.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective, multicenter study in the region of Valencia, which included patients who had undergone urgent or deferred urgent surgery for CAD between January 2004 and December 2009. Data were collected at the end of 2012 in order to assess diverticulitis recurrence and stomal reconstruction. A computer file was provided to interested surgeons and surgical departments for data collection. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the Hospital General Universitario in Valencia.

Variables were analyzed for demographics, comorbidities, surgical indication, operative findings, degree of wound contamination,9 Peritonitis Severity Score (PSS),10 type of intervention and results in terms of hospital stay and 30-day morbidity and mortality, using the modified Clavien-Dindo classification.11 Anastomotic dehiscence or leakage were defined as those diagnosed with clinical repercussions; given the retrospective nature of the study, asymptomatic occurrences were excluded.

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20) statistical software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis U tests were used for independent data in the continuous variables. The association of the categorical variables with morbidity and mortality was analyzed using the χ2 and Fisher's exact tests. We used binary logistic regression to predict the influence of the variables with a P<.1 in the univariate morbidity and mortality study. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsWe analyzed 385 patients, 218 (56.6%) men and 167 (43.4%) women, with a mean age of 64.4 years (SD 15.6), who had undergone surgery at 10 different hospitals. The age range in which most cases occurred was 71–80 (31.4%), while 22.6% were 50 years old or younger. Half of the medical centers were tertiary hospitals (71% of patients) and the rest were district hospitals. The median (25–75th percentiles) time transpired from clinical evolution to surgery was 48h (24–72), and the most common indication was peritonitis (66%).

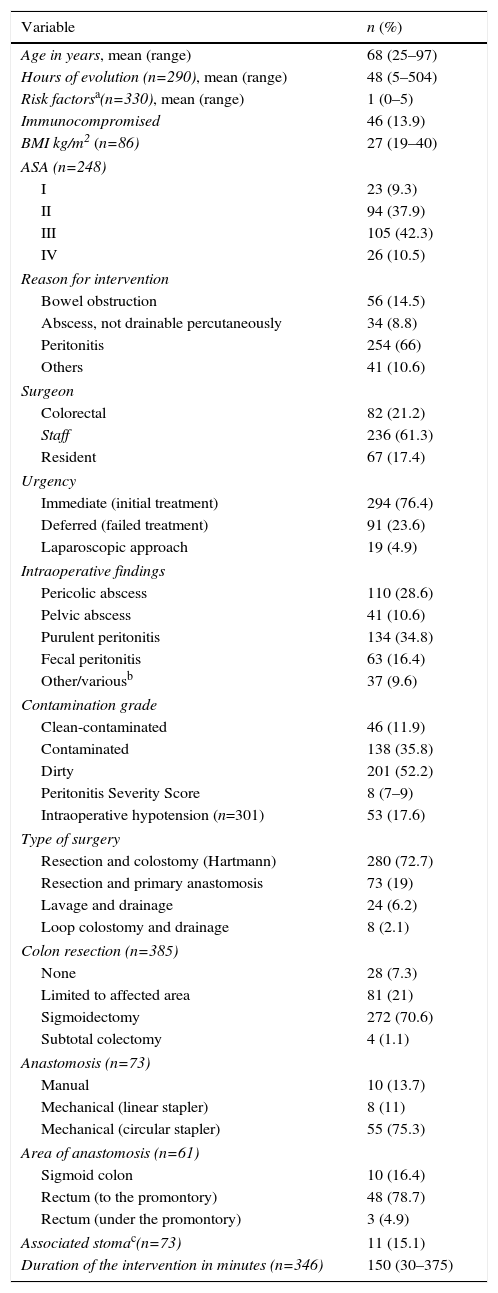

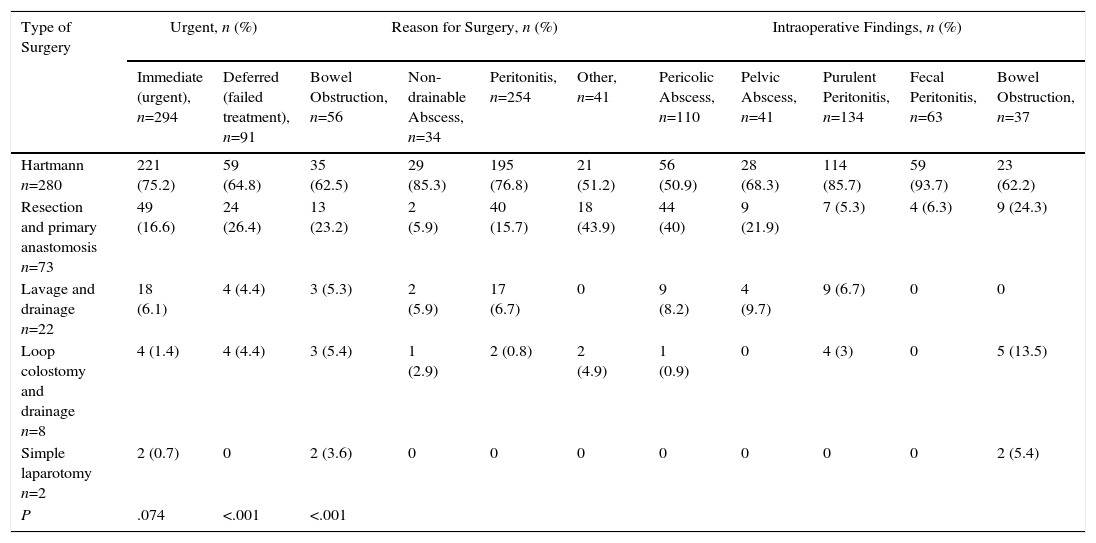

The commonly used approach was open, and the most frequent finding was diffuse purulent peritonitis, followed by pericolic abscess. The most commonly performed intervention was HP (72.2%) (Table 1), regardless of the indication or findings (Table 2). Tertiary hospitals performed more RPA than district hospitals (24 vs 6%, P<.0001). This technique was more often associated with clean-contaminated surgery (43.6%) than with contaminated (28.3%) or dirty (6.9%) surgery (P<.0001). RPA was performed in younger patients than HP: 59.5 (SD 16) versus 65.8 years (SD 15.5) (P=.03). The PSS10 and number of risk factors (NRF) were not related to the type of intervention (P=.2 and P=.783, respectively).

Preoperative Data Related to the Surgical Intervention.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 68 (25–97) |

| Hours of evolution (n=290), mean (range) | 48 (5–504) |

| Risk factorsa(n=330), mean (range) | 1 (0–5) |

| Immunocompromised | 46 (13.9) |

| BMI kg/m2 (n=86) | 27 (19–40) |

| ASA (n=248) | |

| I | 23 (9.3) |

| II | 94 (37.9) |

| III | 105 (42.3) |

| IV | 26 (10.5) |

| Reason for intervention | |

| Bowel obstruction | 56 (14.5) |

| Abscess, not drainable percutaneously | 34 (8.8) |

| Peritonitis | 254 (66) |

| Others | 41 (10.6) |

| Surgeon | |

| Colorectal | 82 (21.2) |

| Staff | 236 (61.3) |

| Resident | 67 (17.4) |

| Urgency | |

| Immediate (initial treatment) | 294 (76.4) |

| Deferred (failed treatment) | 91 (23.6) |

| Laparoscopic approach | 19 (4.9) |

| Intraoperative findings | |

| Pericolic abscess | 110 (28.6) |

| Pelvic abscess | 41 (10.6) |

| Purulent peritonitis | 134 (34.8) |

| Fecal peritonitis | 63 (16.4) |

| Other/variousb | 37 (9.6) |

| Contamination grade | |

| Clean-contaminated | 46 (11.9) |

| Contaminated | 138 (35.8) |

| Dirty | 201 (52.2) |

| Peritonitis Severity Score | 8 (7–9) |

| Intraoperative hypotension (n=301) | 53 (17.6) |

| Type of surgery | |

| Resection and colostomy (Hartmann) | 280 (72.7) |

| Resection and primary anastomosis | 73 (19) |

| Lavage and drainage | 24 (6.2) |

| Loop colostomy and drainage | 8 (2.1) |

| Colon resection (n=385) | |

| None | 28 (7.3) |

| Limited to affected area | 81 (21) |

| Sigmoidectomy | 272 (70.6) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 4 (1.1) |

| Anastomosis (n=73) | |

| Manual | 10 (13.7) |

| Mechanical (linear stapler) | 8 (11) |

| Mechanical (circular stapler) | 55 (75.3) |

| Area of anastomosis (n=61) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 10 (16.4) |

| Rectum (to the promontory) | 48 (78.7) |

| Rectum (under the promontory) | 3 (4.9) |

| Associated stomac(n=73) | 11 (15.1) |

| Duration of the intervention in minutes (n=346) | 150 (30–375) |

ASA: classification of physical state by the American Society of Anesthesiology; BMI: body mass index.

Surgery Performed According to Reason for Indication and Findings.

| Type of Surgery | Urgent, n (%) | Reason for Surgery, n (%) | Intraoperative Findings, n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate (urgent), n=294 | Deferred (failed treatment), n=91 | Bowel Obstruction, n=56 | Non-drainable Abscess, n=34 | Peritonitis, n=254 | Other, n=41 | Pericolic Abscess, n=110 | Pelvic Abscess, n=41 | Purulent Peritonitis, n=134 | Fecal Peritonitis, n=63 | Bowel Obstruction, n=37 | |

| Hartmann n=280 | 221 (75.2) | 59 (64.8) | 35 (62.5) | 29 (85.3) | 195 (76.8) | 21 (51.2) | 56 (50.9) | 28 (68.3) | 114 (85.7) | 59 (93.7) | 23 (62.2) |

| Resection and primary anastomosis n=73 | 49 (16.6) | 24 (26.4) | 13 (23.2) | 2 (5.9) | 40 (15.7) | 18 (43.9) | 44 (40) | 9 (21.9) | 7 (5.3) | 4 (6.3) | 9 (24.3) |

| Lavage and drainage n=22 | 18 (6.1) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (5.3) | 2 (5.9) | 17 (6.7) | 0 | 9 (8.2) | 4 (9.7) | 9 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Loop colostomy and drainage n=8 | 4 (1.4) | 4 (4.4) | 3 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 4 (3) | 0 | 5 (13.5) |

| Simple laparotomy n=2 | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.4) |

| P | .074 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

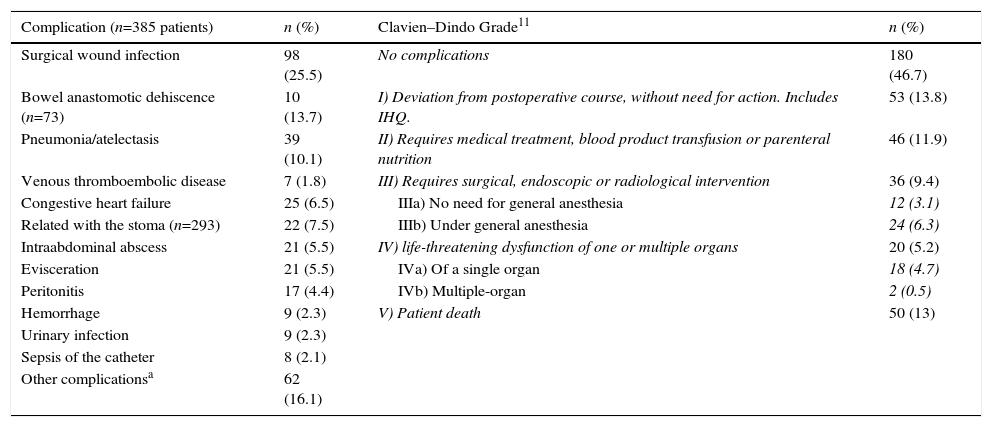

Morbidities were observed in 205 patients (53.2%), including 348 complications and 60 reoperations, and 50 patients (13%) died (Table 3). The most frequent causes were infectious (48.5%), followed by cardiorespiratory. Severe complications were presented by 27.5% of the patients (Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher11).

Postoperative Complications, n=385 Patients.

| Complication (n=385 patients) | n (%) | Clavien–Dindo Grade11 | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical wound infection | 98 (25.5) | No complications | 180 (46.7) |

| Bowel anastomotic dehiscence (n=73) | 10 (13.7) | I) Deviation from postoperative course, without need for action. Includes IHQ. | 53 (13.8) |

| Pneumonia/atelectasis | 39 (10.1) | II) Requires medical treatment, blood product transfusion or parenteral nutrition | 46 (11.9) |

| Venous thromboembolic disease | 7 (1.8) | III) Requires surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention | 36 (9.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 25 (6.5) | IIIa) No need for general anesthesia | 12 (3.1) |

| Related with the stoma (n=293) | 22 (7.5) | IIIb) Under general anesthesia | 24 (6.3) |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 21 (5.5) | IV) life-threatening dysfunction of one or multiple organs | 20 (5.2) |

| Evisceration | 21 (5.5) | IVa) Of a single organ | 18 (4.7) |

| Peritonitis | 17 (4.4) | IVb) Multiple-organ | 2 (0.5) |

| Hemorrhage | 9 (2.3) | V) Patient death | 50 (13) |

| Urinary infection | 9 (2.3) | ||

| Sepsis of the catheter | 8 (2.1) | ||

| Other complicationsa | 62 (16.1) |

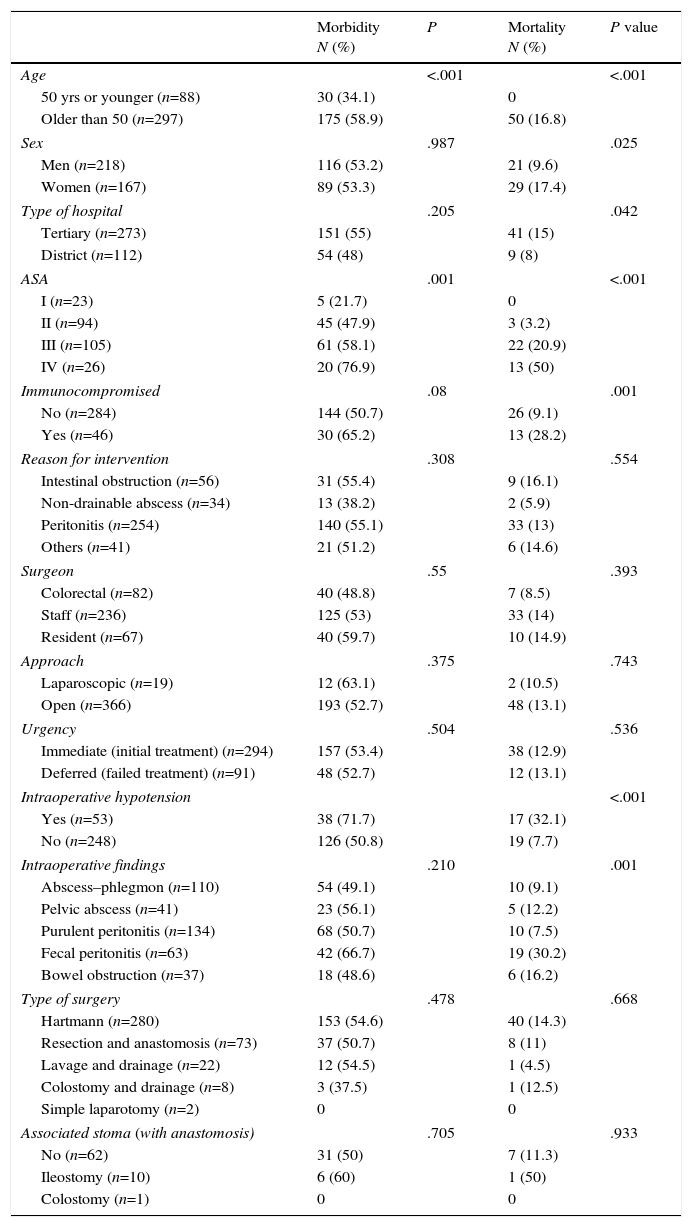

Age, ASA risk, PSS and NRF were associated with risk for morbidity and mortality in patients over the age of 50 (OR=2.7, 95% CI 1.7–4.5, P<.001). Immunocompromised patients had higher mortality (OR 3.9; 95% CI: 1.8–8.3) and higher (but not significant) morbidity. Intraoperative hypotension was associated with mortality (OR: 5.7, 95% CI: 2.7–11.9) (Table 4). Morbidity rates varied widely among hospitals from 33.3 to 65.4% (P=.153), while mortality rates ranged from 5.3 to 29.7% (P=.079).

Morbidity and Mortality of the Intervention According to Different Factors.

| Morbidity N (%) | P | Mortality N (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| 50 yrs or younger (n=88) | 30 (34.1) | 0 | ||

| Older than 50 (n=297) | 175 (58.9) | 50 (16.8) | ||

| Sex | .987 | .025 | ||

| Men (n=218) | 116 (53.2) | 21 (9.6) | ||

| Women (n=167) | 89 (53.3) | 29 (17.4) | ||

| Type of hospital | .205 | .042 | ||

| Tertiary (n=273) | 151 (55) | 41 (15) | ||

| District (n=112) | 54 (48) | 9 (8) | ||

| ASA | .001 | <.001 | ||

| I (n=23) | 5 (21.7) | 0 | ||

| II (n=94) | 45 (47.9) | 3 (3.2) | ||

| III (n=105) | 61 (58.1) | 22 (20.9) | ||

| IV (n=26) | 20 (76.9) | 13 (50) | ||

| Immunocompromised | .08 | .001 | ||

| No (n=284) | 144 (50.7) | 26 (9.1) | ||

| Yes (n=46) | 30 (65.2) | 13 (28.2) | ||

| Reason for intervention | .308 | .554 | ||

| Intestinal obstruction (n=56) | 31 (55.4) | 9 (16.1) | ||

| Non-drainable abscess (n=34) | 13 (38.2) | 2 (5.9) | ||

| Peritonitis (n=254) | 140 (55.1) | 33 (13) | ||

| Others (n=41) | 21 (51.2) | 6 (14.6) | ||

| Surgeon | .55 | .393 | ||

| Colorectal (n=82) | 40 (48.8) | 7 (8.5) | ||

| Staff (n=236) | 125 (53) | 33 (14) | ||

| Resident (n=67) | 40 (59.7) | 10 (14.9) | ||

| Approach | .375 | .743 | ||

| Laparoscopic (n=19) | 12 (63.1) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| Open (n=366) | 193 (52.7) | 48 (13.1) | ||

| Urgency | .504 | .536 | ||

| Immediate (initial treatment) (n=294) | 157 (53.4) | 38 (12.9) | ||

| Deferred (failed treatment) (n=91) | 48 (52.7) | 12 (13.1) | ||

| Intraoperative hypotension | <.001 | |||

| Yes (n=53) | 38 (71.7) | 17 (32.1) | ||

| No (n=248) | 126 (50.8) | 19 (7.7) | ||

| Intraoperative findings | .210 | .001 | ||

| Abscess–phlegmon (n=110) | 54 (49.1) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| Pelvic abscess (n=41) | 23 (56.1) | 5 (12.2) | ||

| Purulent peritonitis (n=134) | 68 (50.7) | 10 (7.5) | ||

| Fecal peritonitis (n=63) | 42 (66.7) | 19 (30.2) | ||

| Bowel obstruction (n=37) | 18 (48.6) | 6 (16.2) | ||

| Type of surgery | .478 | .668 | ||

| Hartmann (n=280) | 153 (54.6) | 40 (14.3) | ||

| Resection and anastomosis (n=73) | 37 (50.7) | 8 (11) | ||

| Lavage and drainage (n=22) | 12 (54.5) | 1 (4.5) | ||

| Colostomy and drainage (n=8) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Simple laparotomy (n=2) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Associated stoma (with anastomosis) | .705 | .933 | ||

| No (n=62) | 31 (50) | 7 (11.3) | ||

| Ileostomy (n=10) | 6 (60) | 1 (50) | ||

| Colostomy (n=1) | 0 | 0 | ||

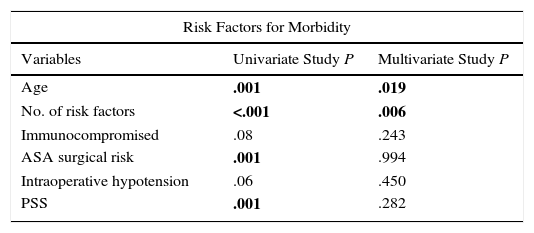

In the multivariate analysis, NRF was more closely associated with morbidity; ASA risk, immunosuppression and PSS were associated with postoperative mortality; age was associated with both (Table 5).

Multivariate Study of The Risk Factors for Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality.

| Risk Factors for Morbidity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariate Study P | Multivariate Study P |

| Age | .001 | .019 |

| No. of risk factors | <.001 | .006 |

| Immunocompromised | .08 | .243 |

| ASA surgical risk | .001 | .994 |

| Intraoperative hypotension | .06 | .450 |

| PSS | .001 | .282 |

| Risk Factors For Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Univariate Study P | Multivariate Study P |

| Age | <.001 | .018 |

| Sex | .025 | .528 |

| Type of hospital | .042 | .998 |

| BMI | .064 | .225 |

| No. of risk factors | <.001 | .225 |

| ASA surgical risk | <.001 | .033 |

| Intraoperative hypotension | <.001 | .097 |

| Immunocompromised | .001 | .034 |

| Operative findings | .001 | .124 |

| PSS | <.001 | .025 |

The multivariate analysis included factors with a significance of P<.1 in the univariate analysis.

In bold: statistically significant.

BMI: body mass index; PSS: Peritonitis Severity Score.

Sixty-two patients (16.1%) were reoperated. The only factor that affected the reoperation rate was the surgery used. Specifically, LPL was associated with 45%, in which 7 stomata were performed, maintaining significance in the multivariate analysis (P=.006). There were also more NRF in patients with evisceration (2.1 vs 1.1; P=.036). This was the most common reason for reoperation (30%), followed by diffuse peritonitis (21.6%), intraabdominal abscess (20%) or necrosis/retraction of the stoma (16.6%).

Colon anastomotic dehiscence (AD) after RPA, a procedure that was only performed in half of the centers, occurred in 13.7%. Manual anastomoses had greater risk than mechanical ones (P=.024), and partial sigmoid resections had a greater tendency for anastomotic leakage than complete sigmoidectomies (33.3% vs 10.9%; P=.067). None of the patients with stoma-protected anastomoses presented leaks.

Out of the 10 patients with anastomotic dehiscence, 3 were treated conservatively, and, out of the 7 who were reoperated, in 6 the anastomosis was converted to terminal colostomy. One patient died of septic shock.

The median overall postoperative stay (25–75th percentile) was 12 days (8–20) (range 1–120). The only factors associated with prolonged hospitalization were advanced age and NRF (P<.001). However, there were significant differences between hospitals (P=.011), ranging from 12 to 21 days. Complicated patients had longer hospital stays (21.9 days; SD 18.5) than uncomplicated patients (10.5 days; SD 5.3, P<.0001). The same was true for patients requiring reoperation (30.6 days; SD 21.4) versus those who did not (14.1 days; SD 12.1, P<.0001).

Over the long term, recurrence of diverticulitis was observed in 13/244 patients (5.3%), which was higher in unresected patients (38.1%) and in those with limited excision to the affected area (4.8%), in whom the sigmoid colon was resected (1.2%, P<.0001). Patients with LPL had a recurrence rate of 41.2%, while those who underwent colostomy and drainage had a recurrence rate of 33.3% versus 1.6% after HP or 2.9% after RPA (P<.0001).

After the initial surgical procedure, 312 patients presented a stoma (301 colostomies and 11 diverting ileostomies).

DiscussionAcute diverticulitis requires urgent surgery in about 25% of patients.3,12,13 It is associated with important morbidity and mortality rates and sequelae, such as the creation of a colostomy that may never be closed.7,8 Despite the tendency to treat mild cases in the outpatient setting,14,15 more cases are considered complex due to age and comorbidities.

The choice of technique is one of the controversies that arise in the management of patients with CAD. Whether to anastomose or not, or whether to maintain a non-resective approach or not, are options influenced by tradition, experience, and even the circumstances of hospital emergency rooms in our setting.

The age and sex distribution of our patients was similar to different Western series.4,16 The median evolution time before surgery was 48h, and only 22% presented no risk factors. The most common were ischemic cardiovascular disease and arteriosclerosis. In our study, 14% of the patients were considered immunocompromised because they presented advanced cancer, were transplant recipients, had renal insufficiency or were being treated with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants or chemotherapy. This rate was lower than that of other studies because this datum, collected according to information from the patients’ medical files, may have been underestimated.17

The most frequent surgical indication was peritonitis. HP was the most frequently used technique (72.7%, which concurs with reports in the literature2–4) and was the most common in all settings, regardless of surgical risk or the surgeon. In cases of diffuse peritonitis, HP was used in almost 90%, to the detriment of RPA, which was performed in only 7% of these cases. It is striking that, in spite of recommendations in the literature,3,18 in 21% of cases the resection was limited to the affected area of the sigmoid colon, and in 16% an anastomosis was made to the sigmoid colon instead of the rectum.

Urgent sigmoidectomy is required when non-surgical treatment fails or in patients with acute peritonitis, which is an important recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence (1B) by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.3 Although short series have been successful with non-surgical treatment, even in patients with pneumoperitoneum, this approach should only be reserved for very stable patients, with no peritoneal signs or severe sepsis.19 After resection, the surgeon may perform an anastomosis, which may or may not be associated with proximal fecal diversion or end colostomy. Evidence from non-randomized studies shows that RPA is not associated with worse outcomes.1,20 The Cleveland Clinic diverticular disease propensity score21 estimates the possibility to create a primary anastomosis or end colostomy using a variety of predictive factors22 and, in a prospective study, patients with higher scores were more likely to have HP.23 Because of bibliographic confirmation bias, surgeons must weigh the individual risks of each case. Thus, hemodynamic instability, acidosis, multiple organ failure and immunosuppression all favor at least a proximal diversion, regardless of the preferences of the surgeon, who may fear conducting reconstructive surgery in an unpromising patient, perhaps in an untimely manner.3,4,18 Although they have limitations, meta-analyses comparing RPA and HP in diffuse peritonitis show comparable mortality rates,22 and Zeitoun et al.,24 in a multicenter randomized trial, observed no differences after having done either resection or colostomy and drainage.

Patients who were 50 years of age or younger had lower surgical risk than older patients, who more frequently presented with hemodynamic instability or a higher PSS, as seen in other studies.10,25 There was a tendency to perform RPA in the younger patients.

When analyzing the hospital parameter, differences were observed in all variables, except for age: RPA was more frequently used at tertiary hospitals, possibly due to the presence of specific units; and, colorectal surgeons conducted more RPA and less HP than non-colorectal surgeons. It should be noted that no patients with stomata protecting their anastomoses experienced dehiscence. A randomized trial between patients with peritonitis who underwent an ileostomy-protected RPA or instead HP had to be interrupted prematurely because the Hartmann reconstruction led to more severe complications (20 vs 0%) than ileostomy. Moreover, the patients with HP had their stomata reconstructed less frequently (57 vs 90%).26

The laparoscopic approach was used very infrequently: LPL was performed in less than 3% of the patients. Case series and retrospective studies have shown the benefits of this technique in purulent peritonitis27 because of its low mortality, fewer stomata and wound infections, while causing no differences in recurrence versus resective techniques. Nonetheless, the low methodological quality of these studies, leaving a septic focus, and the lack of prospective studies after the initial Myers et al. study28 have continued to limit its use. In short, there is still no evidence to consider it an adequate alternative to colectomy.3 Although recent randomized trials show faster immediate postoperative recovery with less discomfort, LPL has not been proven superior to resective techniques. It seems to control sepsis in 80% of cases, without requiring subsequent surgery in 50%.5,6,29–32 In any case, its indication would be for purulent peritonitis in non-immunocompromised patients or those with high surgical risk, in whom no perforation is evident. This requires not only a surgeon experienced in laparoscopic approaches, but also greater radiological discrimination between diffuse and fecal peritonitis and better diagnosis of perforated cancers to define its use.33

Our morbidity and mortality rates concur with those reported in the literature,20,34 and there were no differences between patients who were operated on urgently and those with treatment failure. Overall infectious complications accounted for 48.5%, and the most frequent cause of mortality was multiple organ failure/septic shock in 72% of patients. As for factors related to postsurgical morbidity, the multivariate study only identified age and NRF. Age, ASA, immunosuppression and PSS with a higher risk of mortality were similar to other series.3,4,35 The only factor that affected reoperation rate was the technique used. There was an elevated rate of intraabdominal abscesses and 45% of reoperations after LPL, which should make us consider assessing the specific indications of this technique.

The risk of morbidity and mortality has directed attention toward more conservative options. Sallinen et al.36 advocate non-operative treatment in patients with small amounts of ectopic air without clinical signs of peritonitis. This is in line with changes toward less aggressive strategies,16,19 given the postoperative complication and reoperation rates. This therapeutic approach, however, must be reserved for very select cases.3

Anastomotic dehiscence occurred in 13.7% of patients with RPA. There was more risk among the cases with manual anastomosis, possibly associated with smaller resections. It should be remembered that the entire sigmoid colon should be removed with the distal resection margin at the sacral promontory and anastomosis to the upper rectum. This ensures less recurrence and reduces the risk for anastomotic dehiscence by providing the rectal stump with adequate vascularization.3,18,37,38

The postoperative hospital stay was long in our series. There was, however, significant variation among hospitals, reflecting differences in the case-mix as well as in perioperative patient management. Even given the inherent biases of this study, the recurrence of diverticulitis was notably superior in the non-resected patients and in those with limited resections or anastomosis to the sigmoid colon. Specifically, after LPL, 41% of patients presented recurrence versus less than 2% when resection had been performed.

Laparoscopic resection has been shown to be safe for treating patients undergoing elective colectomy for diverticulitis.3,38 The literature also supports this approach in CAD and, given the technical difficulties, manual assistance (hand port) may be useful in some cases.39 Nonetheless, only 4.9% of our patients were treated with a laparoscopic access: 10 with LPL, 5 HP and 4 RPA. The follow-up of randomized series of resections due to CAD reflects comparable results in gastrointestinal quality of life and recurrence of diverticulitis,40 although laparoscopic resection is technically difficult and requires training, experience and selection of suitable cases.3

In conclusion, our study presents the weaknesses of being retrospective, and the data is therefore less homogeneous and not very recent. In contrast, its strength is that we have compiled case data from 10 hospitals, with a sample of 385 patients who had been treated. In our setting, patients with CAD generally required urgent surgery for peritonitis and were treated with laparotomy. Purulent peritonitis was the most frequent finding. The most commonly used technique was HP, although there were differences in the caseload and in the technique used when the different hospitals were compared. The considerable morbidity and mortality rates, as well as postoperative stays (without even taking into account the presumed reconstruction of the digestive tract after HP), and the high rate of reoperation after LPL, make it necessary to propose strategies like RPA. Whether or not it is protected with a stoma, we have seen no increase in postoperative incidences, and the technique is able to resolve the problem definitively.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Marta Aguado, Javier Aguiló, Zutoia Balciscueta, Sylvia Barros, Juan Carlos Bernal, Miriam Cantos, Javier Espinosa, Matteo Frasson, Rafael García-Calvo, Eduardo García-Granero, Lucas García-Mayor, Juan Hernandis, Francisco Landete, Félix Lluís, David Martínez-Ramos, Emilio Meroño, Isabel Rivadulla, Rodolfo Rodríguez, María Dolores Ruiz, José Vicente Roig, Vicente Roselló, Antonio Salvador-Martínez, Natalia Uribe, Celia Villodre.

Please cite this article as: Roig JV, Salvador A, Frasson M, Cantos M, Villodre C, Balciscueta Z, et al. Tratamiento quirúrgico de la diverticulitis aguda. Estudio retrospectivo multicéntrico. Cir Esp. 2016;94:569–577.