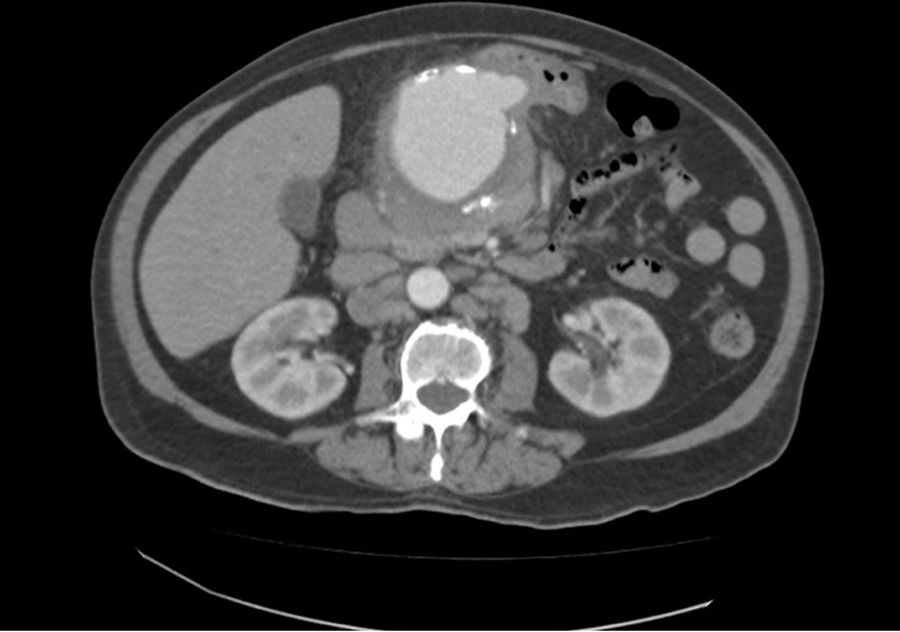

We present the case of an 80-year-old male admitted for fever of unknown origin, presenting only a positive blood culture for Salmonella spp. Among the complementary tests ordered, CT angiography identified a common hepatic artery aneurysm with a maximum diameter of 78mm (Fig. 1), and PET/CT scan demonstrated intense metabolic activity in the region of said aneurysm. After the administration of antibiotic treatment with ciprofloxacin and fever remission, the patient was discharged pending surgery, which was not performed during admission for personal reasons of the patient. Two weeks later, the patient came to the emergency room for abdominal pain and asthenia, and a pulsatile mass was detected in the epigastrium on physical examination. After performing another CT angiography, which showed increased size of the mycotic hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) associated with signs of contained rupture, emergency surgery was indicated and these findings were confirmed intraoperatively.

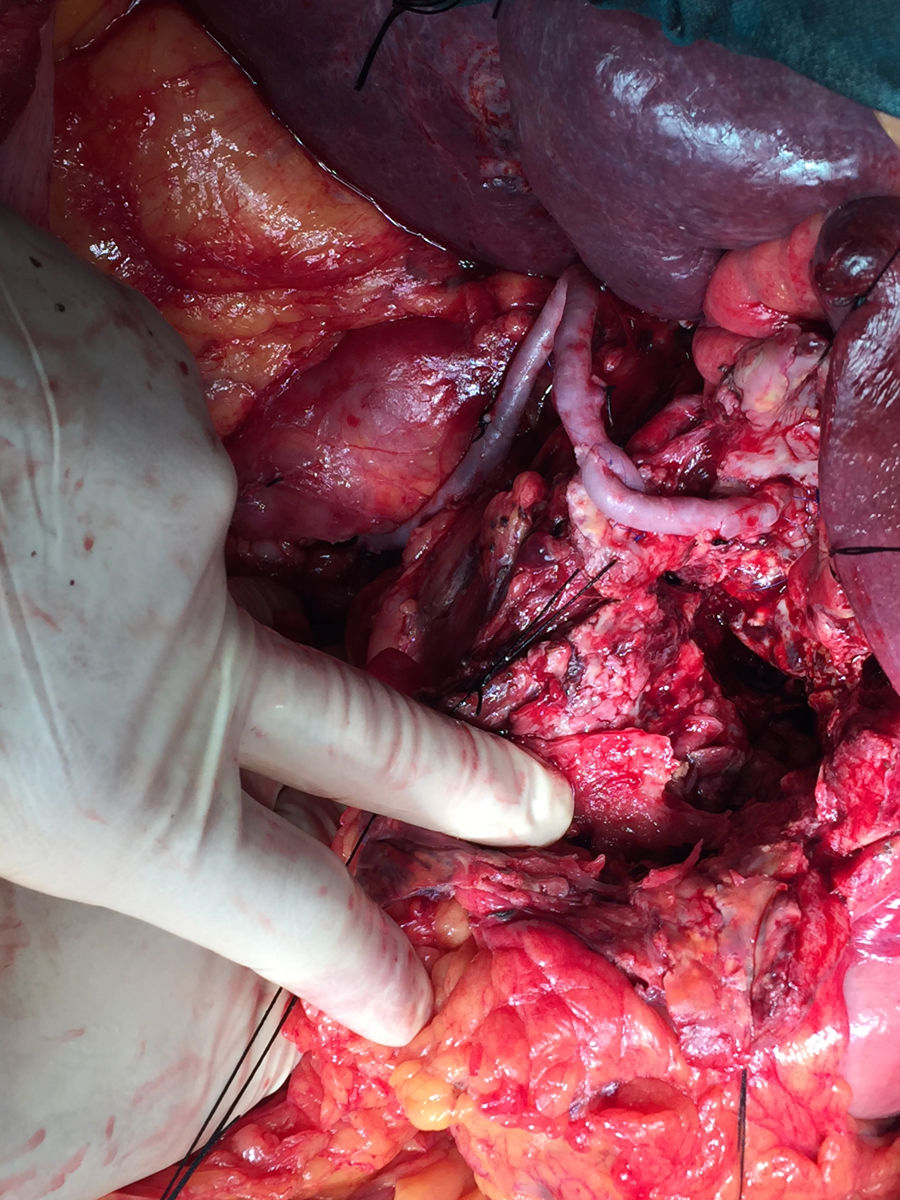

Vascular control was achieved of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery. During the clamping of the trunk, the intima was injured, making ligation necessary. We therefore decided to perform a retrograde bypass (with inverted left saphenous vein) from the infrarenal aorta to the bifurcation of the common hepatic artery, and from there to the proximal portion of the common hepatic artery (near the celiac trunk) to ensure retrograde circulation to the left splenic and gastric arteries, finding no signs of visceral hypoperfusion (Fig. 2). The duration of ischemia was approximately 4h. Patient progress during the postoperative period was satisfactory. The only complication was a postoperative pancreatic fistula, which was managed conservatively, and the patient was discharged 2 weeks after the procedure.

The concept of mycotic aneurysm arose in 1885 following the study of infected aneurysms secondary to bacterial endocarditis.1,2 They are very rare, with an incidence of 0.8%–3.2% of all aneurysms.3 In descending order, they are located in the abdominal aorta, peripheral (femoral), cerebral and visceral arteries, with the superior mesenteric being the most frequently involved.4

In the pre-antibiotic era, the most frequent cause of its development was bacterial endocarditis with the development of septic emboli that settled on the vessel wall, which could be healthy or have intimal lesions. Other explanations of its genesis are the infection of a previous arteriosclerotic aneurysm (due to infections adjacent to the aneurysm or bacteremia) and the appearance of post-traumatic pseudoaneurysms, with a greater role in recent decades secondary to parenteral drug addiction and endovascular procedures. The pathogenesis is secondary to the septic embolus penetrating the vasa vasorum, causing an infection of its wall with the consequent destruction and the development of the aneurysm. This would explain the cases secondary to septic emboli, or an infection adjacent to the vessel that would erode the arterial wall until the aneurysm was formed.1,4 The most frequently involved germs are Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.4,5 The profile of the typical patient is an individual in the 7th decade of life with some degree of immunosuppression, such as neoplasms, corticosteroid treatment, etc.2,3,6

The most frequent clinical presentation of HAA is abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium. In up to 80% of cases, rupture is the form of presentation of HAA, which can be to the peritoneal cavity, biliary tree or digestive tract. If the rupture occurs in the biliary tree, the classic triad consists of jaundice, abdominal pain and digestive tract bleeding7,8; meanwhile, if it occurs in the digestive tract, there will be no jaundice. The diagnosis is based on imaging tests, mainly CT angiography, which shows mycotic aneurysms as lobed vascular masses with irregular arterial walls and perilesional edema.4

The treatment of HAA continues to be debated and is a challenge for surgeons. This is based on a series of premises, such as adequate antibiotic treatment or the duration of treatment. Although it seems clear that it should be a minimum of 2 to 8 weeks, there are authors who advocate lifelong treatment and the definitive treatment of the aneurysm, either endovascular or surgical. This is of the treatment of choice in complicated HAA, especially in the scenario of an aneurysmal rupture. Surgery involves excision of the aneurysm and debridement of the perilesional infected tissue associated or not with the arterial re-anastomosis, using prostheses or autologous grafts. Endovascular treatment, with infection permanence rates of up to 23%, entails embolization or stent placement. However, there are few data about their long-term efficacy or the need for subsequent surgical intervention in many cases to definitively treat HAA.6,9,10

We would like to thank the vascular surgery unit at our hospital for their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Martí-Fernández R, Muñoz-Forner E, Machado-Fernández F, Martín-González I, Garcés-Albir M. Tratamiento quirúrgico de un aneurisma micótico roto de la arteria hepática. Cir Esp. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2019.07.009