Duodenal diverticula are acquired lesions that generally appear in the second duodenal portion,1,2 with a prevalence in the general population that is around 20% and increases with age.1–4 Although they may present as a potentially fatal emergency complication, duodenal diverticula are usually either asymptomatic or manifest as recurring choledocholithiasis.1–3 Therefore, surgical bilioenteric bypass could be considered a safe, effective treatment.

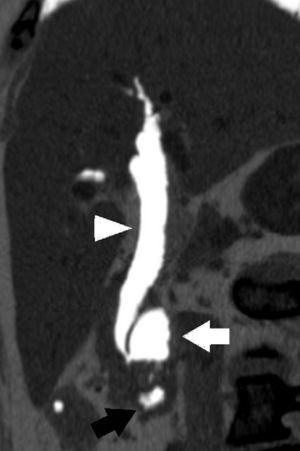

We present the case of a 75-year-old woman with a medical history of arterial hypertension, mild mitral insufficiency and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 2007 due to non-complicated symptomatic cholelithiasis. One year after cholecystectomy, she was diagnosed with choledocholithiasis due to dyspepsia and altered liver function, requiring endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatectomy (ERCP) with sphincterotomy on 2 separate occasions. The endoscopic procedure revealed evidence of the presence of a juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum (JDD). Afterwards, she presented isolated episodes of mild abdominal pain. In November 2010, the patient came to our Emergency Department complaining of intense sudden-onset epigastric pain that radiated toward both flanks of 12h duration, with no jaundice or other symptoms. The work-up demonstrated moderately high transaminases (AST/ALT: 339/183IU/L). Abdominal ultrasound showed pneumobilia and a 12mm common bile duct with a hyperechogenic image in the interior compatible with lithiasis. It was decided to hospitalize the patient and an abdominal computed tomography was performed, as it was impossible to carry out magnetic resonance tests due to claustrophobia. Oblique multiplanar reconstruction revealed a dilated common bile duct with important pneumobilia and the presence of a non-complicated duodenal diverticulum measuring 36mm×20mm in apparent relation with the dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 1). After clinical improvement with medication and normalization of blood tests, we decided to operate with intraoperative cholangiography, which confirmed the findings of bile duct dilation and giant juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum with an anterior-superior projection. We therefore proceeded with complete dissection of the bile duct, distal ligature and bilioenteric bypass by means of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The patient presented a non-eventful post-op recovery, and she currently has satisfactory outpatient follow-ups with no recurrence of the previous gastrointestinal symptoms.

The point of least resistance in the duodenal wall is at the ampulla of Vater because it is at this point where the circular configuration of the duodenal musculature becomes less structured in order to integrate with the sphincter of Oddi. It is assumed that this is why most duodenal diverticula appear in the juxtapapillary region, and may even encompass the papilla.2 Whether the presence of a JDD conditions significant dysfunction at the sphincter of Oddi is still controversial since there are contradictory manometric studies in the literature.5,6 There is no evidence of local histologic fibrous or inflammatory changes,4 nor has any specific association been reported between JDD and neoplastic disease.7

It does seem to be proven, however, that the existence of JDD correlates with the appearance of painful biliopancreatic disease in the upper hemi-abdomen, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis or acute pancreatitis.1–4 The proposed mechanisms for this association are extrinsic compression of the bile duct (Lemmel's syndrome) and the colonization of the JDD by β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria.8 These bacteria would ascend through the bile duct, decomposing the bilirubin conjugated into glucuronic acid and unconjugated bilirubin, which would later transform into calcium bilirubinate, precipitating to form the brown-pigmented gallstones that characteristically appear in the lithiasis associated with JDD. These cases of choledocholithiasis, even cholangitis secondary to Lemmel's syndrome,9 may be treated satisfactorily with endoscopy. Although the cannulation of the papilla may be more laborious, the most recent studies do not demonstrate an increase in the risk of complications associated with ERCP with sphincterotomy and/or extraction of calculi.2,3,9,10 Nonetheless, the recurrence of choledocholithiasis after effective endoscopy is greater than in patients without JDD (6% vs 1.5%).10

Duodenal diverticula have also been associated with potentially fatal complications, such as upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, intestinal obstruction or perforation of the diverticulum (generally retroperitoneal). These complications can evolve into very serious conditions, including sepsis or massive hemorrhage. There is no doubt about the need for emergency surgery in these situations, and diverticulectomy is proposed as the surgical technique of choice. Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that this procedure presents a mortality of up to 30%.1

In summary, no intervention is necessary when asymptomatic JDD is an incidental finding.1,2 Cases with associated choledocholithiasis can be initially treated with standard endoscopic techniques.3 When recurring symptoms occur, however, we believe that the surgical option should be considered. Although the limited number of patients in whom surgery could play a role makes it difficult to establish conclusions, it seems coherent to think that this should be centered on the bypass of the bile duct, either by hepaticojejunostomy as in most cases or, as an exception, by means of choledocoduodenostomy. The derived morbidity and mortality and the absence of neoplastic association do not justify diverticulectomy or extensive resection of the bile duct in non-complicated situations.

Please cite this article as: Beisani M, Espin F, Dopazo C, Quiroga S, Charco R. Manejo terapéutico del divertículo duodenal yuxtapapilar. Cir Esp. 2013;91:463–465.