Transanal endoscopic operation (TEO) may be the technique of choice for the treatment of rectal lesions, both benign and selected malignant lesions, with similar survival rates to conventional surgery but with lower morbidity.

MethodsIn this article we present a series of 70 patients operated on with this procedure (TEO) in our centre. The indications were benign rectal lesions and malignant lesions at early stages (T1) 86%. The surgical procedure was performed with the transanal endoscopic operation platform (TEO; Karl Storz, Tüttlingen, Germany) and ultrasonic scalpel (Harmonic scalpel, Ethicon Endo-surgery, …).

ResultsThe indication in 43 patients was a benign lesion (adenoma), in the other 27 the diagnosis was adenocarcinoma. After the resection, 61% of the series had a malignant lesion in the pathology report: 13 patients of the 43 with a benign lesion initially had a malignant lesion in the pathology report. Postoperative morbidity was 36%, Clavien III (5.7%). 3 patients (4%) needed emergency surgery.

All of the benign lesions were completely excised, but 7 malignant lesions had resection margin involvement The median follow-up time was 26.4 months (range 1–71 months), the overall recurrence for benign tumours was 9%, 8% for malignant pT1 and 12.5% for malignant pT2. Early salvage surgery was performed on 8 patients.

ConclusionsTEO allows us to excise benign rectal lesions that could not be excised with a conventional approach (endoscopic or transanal resection) with a low morbidity rate. TEO can be used for malignant rectal tumours in early stages (pT1) with pathological confirmation.

La cirugía endoscópica transanal puede ser la técnica de elección para el tratamiento de las lesiones rectales, tanto benignas como malignas seleccionadas, con cifras de supervivencia equiparables a la cirugía convencional y tasas de morbilidad más bajas.

MétodosPresentamos una serie de 70 pacientes intervenidos por operación endoscópica transanal (TEO); las indicaciones fueron lesiones rectales benignas o malignas en estadio precoz (T1) 86%. La cirugía se instrumentó con un sistema TEO (Karl Storz, Tüttlingen, Alemania) y bisturí armónico (Harmonic scalpel, Ethicon Endo-Surgery).

ResultadosEn 43 pacientes la indicación fue lesión adenomatosa; en los 27 restantes el diagnóstico preoperatorio fue de adenocarcinoma. Sin embargo, tras la resección, 47% mostraron lesión maligna en el resultado anatomopatológico, incluyendo 13 de los 43 considerados inicialmente como benignos. La morbilidad postoperatoria global fue del 36%, Clavien III (5,7%), precisando reintervención inmediata 3 (4%).

Todas las lesiones benignas se resecaron de forma completa y 7 malignas presentaron afectación del margen de resección. Con un seguimiento medio de 26,4 meses (1–71), la recidiva para tumores benignos ha sido del 9% para pT1 del 8% y, para pT2, del 12,5%. Precisaron nueva cirugía 8 pacientes.

ConclusionesLa TEO permite extirpar tumores benignos de recto no resecables mediante resección endoscópica o transanal con un bajo índice de morbilidad. También está indicada en el tratamiento curativo de las neoplasias malignas de recto que se confirman histológicamente como carcinomas pT1 de buen pronóstico.

Transanal endoscopic operation (TEO) was started by Buess1 in the eighties, in response to the difficulties encountered with low rectal neoplasias.

Many indications have been proposed for TEO instruments; the most frequent of these being the resection of rectal adenomas.2,3 Other indications accepted at present are: the excision of carcinomas with involvement of the rectal mucosa (T1), in which we can achieve oncological resections with lower morbimortality rates than total mesorectal excision and equal long term results4–6; and in cancers with involvement up to the muscular rectalis (T2), in the context of clinical trials including additional treatment with chemo or radiotherapy.7,8 If the tumour has spread beyond the muscle or if there is the suspected possibility of infiltrated lymph nodes T3 or N(+), the indication would only be palliative in patients with high comorbidities, or those rejecting an abdominoperineal excision.

In studies and under research there are other applications for TEO, such as: complete clinico-pathological regression in T2–T3 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy and residual scar resection9–11 and complete mesorectal excision in T2N0 lower or mid rectal tumours with subsequent coloanal anastomosis.12

Other less frequent tumour indications applying TEO would be carcinoid tumours and tumours of the gastrointestinal stroma.13,14

Patients and MethodsWe need specific instruments to perform this surgical technique; Storz TEO equipment and ultrasonic scalpel (Ultracision Harmonic Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Karl Storz, Tüttlingen, Germany) in our case, which greatly facilitated control of haemostasis.

All cases were assessed preoperatively using endoscopy and biopsy. Endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) was performed or magnetic nuclear resonance (MNR) preoperatively or computerised axial tomography (CT) in tumours larger than 3cm or with a biopsy of adenocarcinoma. We took new biopsies when there was suspicion of invasion of the second layer in some of the previous tests and when the previous biopsy had shown villous adenoma. Mechanical cleansing of the colon was performed using oral preparations of mono and disodium phosphate (Fosfosoda Casen-Fleet, Saragossa, Spain).

We positioned the patient on the operating table in such a way that the lesion was situated in the lower part of the rectoscope. We performed the excision of complete wall thickness in all cases. We sutured the rectal wall defect.

We followed the preoperative classification with therapeutic intent for TEO considering groups i and ii curative (adenomas and T1 good prognosis), with consensus intent group iii (T2) and palliative intent group iv (T3).15 The distance from the anal margin for performing TEO was between 4 and 15cm.

Rigid rectoscopy was performed in the clinic every three months for the first two years during follow-up of these patients, for both benign and malignant lesions. In addition, CEA was performed every three months and abdominal ultrasound/CT every six months during follow-up.

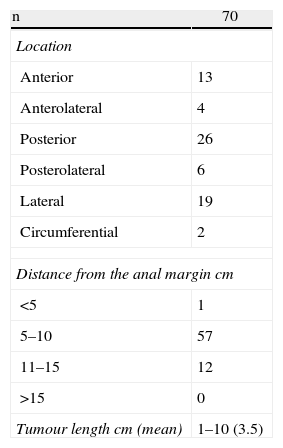

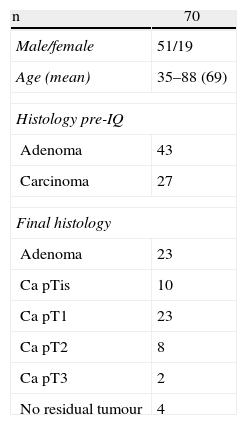

ResultsOur experience includes seventy patients who were operated consecutively using TEO from July 2006 to March 2012. They included 51 males and 19 females with a mean age of 69. They were classified by the anaesthesia scale of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) as: 8 patients grade I, 31 patients ASA II, 25 ASA III and 5 ASA IV.

The site and height at which the lesion was found is shown in Table 1. In the specimens for pathological analysis the mean size of the benign lesions was 4.1cm (range: 1.5–10cm) and of the malignant lesions 3.2cm (range: 1–6cm). The final histology is shown in Table 2.

Amongst the malignant lesions, seven corresponded to T2–T3N0 tumours; four of which were staged with MRI and ERUS as T2N0; TEO technique was used in three due to major comorbidities and another due to hepatic metastases from an original tumour which was not in the digestive tract. The three cases which had been diagnosed preoperatively as T3N0M0 in those where a TEO technique was used had cirrhosis Child stage B, C, a stage IV pancreatic neoplasm, and the third was given neoadjuvant therapy with chemotherapy and radiotherapy after which a clinical complete regression was seen.

Perforation of the anterior wall of the rectum was a surgical complication which we could not close transanally; conversion to laparotomy was performed.

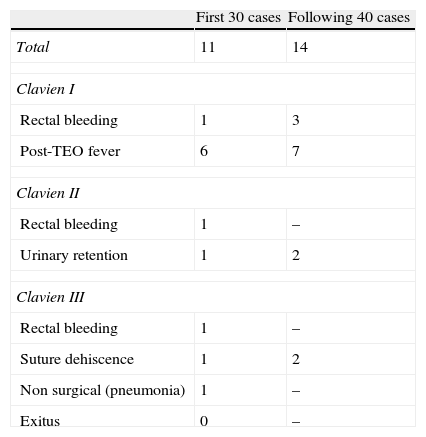

Overall postoperative morbidity was 35.7% (25 out of 70). Using the Clavien classification16,17 17 were grade i, four were grade ii and four grade iii. Eleven out of the 30 first operated cases presented some type of morbidity and fourteen of the remaining 40 had morbidity. All the morbidity developed in patients with curative intent (Table 3). Of the 4 Clavien III patients, three presented with rectal suture dehiscence and one with rectal bleeding, the dehiscence manifested as rectal bleeding, presacral abscess and pelvic peritonitis. The rectal bleeding needed laparotomic rectal resection. One patient with dehiscence underwent a further TEO for haemostasis. Another patient with pelvic peritonitis underwent lavage of the pelvic cavity, rectal suturing and protective ileostomy and finally the third patient with dehiscence of half of the rectal circumference and a presacral abscess, underwent repeated lavage of the residual cavity and a protective ileostomy.

Long/medium term complications were: three cases presenting with transitory incontinence, two for gas and one for liquid stools, which resolved after two to three months, respectively.

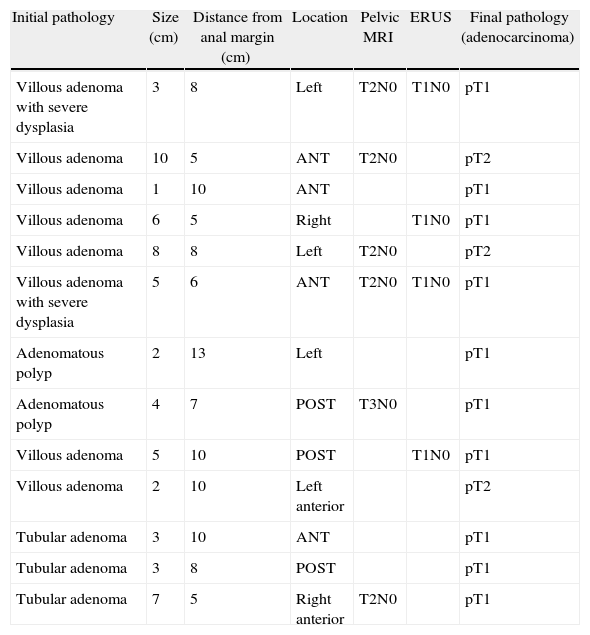

Preoperative pathology reported 27 malignant lesions and 43 benign lesions. The anatomo-pathological result from the final specimen was: 33 malignant lesions, 33 benign lesions and in four cases no residual tumour was found (Table 4). In thirteen cases of previously benign lesions, after resection and pathology study, ten cases were pT1 and three were pT2.

Lesions With an Initial Benign Diagnosis and Malignant Pathological Anatomy of the Surgical Specimen (Adenocarcinoma).

| Initial pathology | Size (cm) | Distance from anal margin (cm) | Location | Pelvic MRI | ERUS | Final pathology (adenocarcinoma) |

| Villous adenoma with severe dysplasia | 3 | 8 | Left | T2N0 | T1N0 | pT1 |

| Villous adenoma | 10 | 5 | ANT | T2N0 | pT2 | |

| Villous adenoma | 1 | 10 | ANT | pT1 | ||

| Villous adenoma | 6 | 5 | Right | T1N0 | pT1 | |

| Villous adenoma | 8 | 8 | Left | T2N0 | pT2 | |

| Villous adenoma with severe dysplasia | 5 | 6 | ANT | T2N0 | T1N0 | pT1 |

| Adenomatous polyp | 2 | 13 | Left | pT1 | ||

| Adenomatous polyp | 4 | 7 | POST | T3N0 | pT1 | |

| Villous adenoma | 5 | 10 | POST | T1N0 | pT1 | |

| Villous adenoma | 2 | 10 | Left anterior | pT2 | ||

| Tubular adenoma | 3 | 10 | ANT | pT1 | ||

| Tubular adenoma | 3 | 8 | POST | pT1 | ||

| Tubular adenoma | 7 | 5 | Right anterior | T2N0 | pT1 |

ANT: anterior; ERUS: endorectal ultrasound; polyp: adenomatous polyp; POST: posterior; MRI: magnetic resonance.

The majority of the benign lesions were villous adenoma polyps with a greater or lesser degree of dysplasia, R0 resection was achieved in 100% of the patients.

With regard to the lesions which proved malignant in the end, there were 23 T1 carcinomas, of which four had affected margins, eight T2 lesions, two of which had affected margins and two T3 lesions, one of which had deep resection margin involvement.

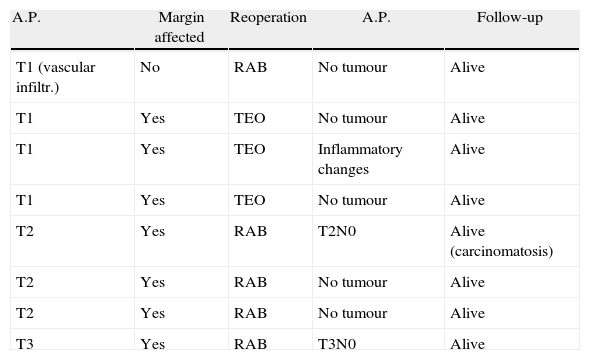

An immediate salvage operation was performed on the pT1 patients with affected margins, a new TEO was performed in three, and a fourth patient was not reoperated on due to serious comorbidities. In one pT1 patient we performed a laparoscopic total mesorectal excision due to poor prognostic factors (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with vascular spread). Four of the pT2 and pT3 lesions were not resected due to extremely high comorbidities and a further T2 was not resected as the patient refused. The remainder underwent radical surgery with rectal resection and mesorectal excision, as shown in Table 5.

Early Reoperations.

| A.P. | Margin affected | Reoperation | A.P. | Follow-up |

| T1 (vascular infiltr.) | No | RAB | No tumour | Alive |

| T1 | Yes | TEO | No tumour | Alive |

| T1 | Yes | TEO | Inflammatory changes | Alive |

| T1 | Yes | TEO | No tumour | Alive |

| T2 | Yes | RAB | T2N0 | Alive (carcinomatosis) |

| T2 | Yes | RAB | No tumour | Alive |

| T2 | Yes | RAB | No tumour | Alive |

| T3 | Yes | RAB | T3N0 | Alive |

A.P.: Pathological anatomy; RAB: low anterior resection.

During follow-up, all T2–T3 patients who had not been salvaged, except one, died as a result of their comorbidities or other tumours. One T1 patient developed a sigmoid neoplasm.

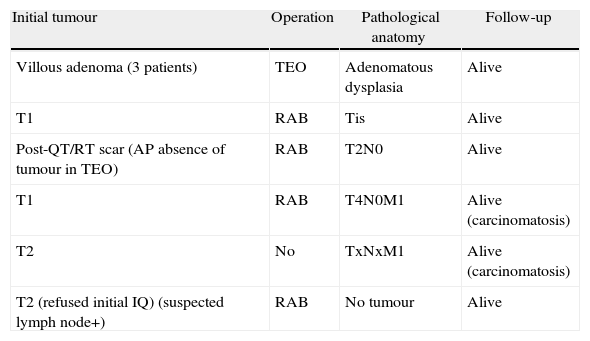

There was recurrence in seven patients, three villous adenomas, two T1 tumours and two T2 tumours. Their surgery, pathological anatomy and evolution are shown in Table 6.

Recurrence and Follow-up.

| Initial tumour | Operation | Pathological anatomy | Follow-up |

| Villous adenoma (3 patients) | TEO | Adenomatous dysplasia | Alive |

| T1 | RAB | Tis | Alive |

| Post-QT/RT scar (AP absence of tumour in TEO) | RAB | T2N0 | Alive |

| T1 | RAB | T4N0M1 | Alive (carcinomatosis) |

| T2 | No | TxNxM1 | Alive (carcinomatosis) |

| T2 (refused initial IQ) (suspected lymph node+) | RAB | No tumour | Alive |

AP: pathological anatomy; IQ: surgery; QT/RT: chemotherapy+radiotherapy; RAB: low anterior resection of the rectum.

40% of the population will develop benign polyps or adenomas of the rectum; it will be possible to resect the majority by endoscopic polypectomy,17 but large lesions or extensive flat polyps cannot be removed in this way. Rectal resection using a transabdominal or transacral approach is a surgical procedure which is associated with significant morbidity (7%–68%) and mortality (0%–6.5%). Using a TEO technique is a valid alternative to these approaches.

A proportion of tumours diagnosed as adenomas preoperatively turn out to be carcinomas on final anatomopathogical analysis. If the parietal resection performed was of complete thickness and the final pathology staged the lesion as pT1 with favourable prognostic factors, the safe parietal margins which we obtain by TEO resection are adequate and for these this resection represents a radical procedure and definitive treatment, given that possible lymph involvement is near 0%–8% (T1).4–6,17 With regard to T2 carcinomas, therapeutic options associated with local surgery give diverse results in terms of recurrence and survival and their treatment with TEO, with which we only resect the rectal wall, is not accepted at present due to the possibility of lymph involvement of up to 20%; for this reason they need to be treated with mesorectal resection surgery four to six weeks after initial transanal resection. Concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy have achieved better local control of rectal neoplasias and allow, in cases of complete histological and clinical response, resection of the residual scar using TEO with a view to confirming this complete response, but always within clinical trials,9 because it has been seen that it does not decrease survival in these patients compared to low anterior resection and because we always have a salvage margin against relapse with radical abdominal surgery and without altering overall survival.9,10

In our patients, once the pathological analysis of the specimens had been performed, we obtained a diagnosis of adenoma in 33, ten of which showed severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ. 23 patients were labelled pT1, eight were pT2, two patients were pT3 and pathological analysis did not reveal a tumour in four (in three of these TEO was used to resect the previous scar of an endoscopic resection of an adenoma with infiltration of the stalk by adenocarcinoma. In the fourth patient the scar resulting from a T3N0M0 tumour was resected, which had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy and the patient, along with their surgeon, suggested a transanal endoscopic resection because of comorbidities.

Complications associated with TEO vary between 20% and 30%.18 Mild rectal bleeding, urinary retention and fever are Clavien I–II complications, with simple treatment. However 5% will be major complications (Clavien III) such as organ-space infection, severe bleeding and perforation in the peritoneal cavity.19 In our study, despite having performed TEO in patients with adenomas larger than 3cm in 80%, of which 18.3% were sited at more than 10cm from the anal margin and 50% of the latter were anterior or lateral, Clavien I–II complications were 30% and Clavien III were 5.7%. The 30 first cases had morbidity similar to the 40 following cases because, as we advanced in experience, we were including more complex cases. This morbidity increased if the TEO had been performed to extract a residual scar in T2–T3 tumours which had received neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy, up to 53%.9,10 If the complication in a high tumour is perforation in the abdominal cavity, several authors11,18,19 report that this does not require conversion to another approach route as it can be safely repaired endoscopically. In our experience, conversion to abdominal surgery was necessary because an intraperitoneal perforation presented.

Another complication with this technique is suture dehiscence. This can occur in more than 50% of cases and has no clinical consequences as the parietal defect is small and infraperitoneal, therefore some authors recommend not closing these defects.20,21 It is a different matter if the dehiscence occurs after a large parietal closure, which we, as other authors, believe should be closed,15 because otherwise bleeding and stenosis can be caused, and even presacral abscesses requiring drains and successive cleansing. In our series, dehiscence presented in 50% of patients, but only in three (4%) cases did the dehiscence cause major complications with clinical repercussions making reoperation necessary.

Manometry and rectal ultrasound were used to study continence and it was seen that there are no long-term disturbances of the sphincter.22–25 In our patients there were two cases of gas incontinence and one case of liquid stool incontinence which resolved satisfactorily after two and three months.

The rates of recurrence of benign lesions were around 5%, the main factors associated with this were the size of the tumour, insufficient margins or the presence of dysplasia in the edges of the specimen.26,27 In our series of 33 patients with adenomas, three (9.1%) relapsed and for all of them, there was dysplasia in one of the resection margins on the first anatomo-pathological analysis of the specimen.

With regard to pT1 and pT2 lesions, the mean rates of relapse after one year varied between 10% and 25% respectively28–30 and are directly associated with resection margins of less than 1cm and with tumour factors with a poor prognosis. The treatment of this relapse in patients with serious morbidities can sometimes be a new excision and adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy. In patients with or without acceptable comorbidities, endoluminal or pelvic recurrence must be treated with an immediate radical salvage operation. In our series, four patients with infiltrating tumours (10.8%) presented local recurrence. Two were pT1 (8.7%), one was pT2 (12.5%) and one was pT3 (50%) the rectal scar of which had been resected using TEO, after neoadjuvant therapy with an anatomopathological diagnosis of absence of tumour in the surgical specimen.

We believe that our series presents a high percentage of benign lesions that turned out to be malignant on final pathological diagnosis. This is due to the fact that macrobiopsies are not used during colonoscopy. Furthermore, with an initial diagnosis of villous adenoma in many cases and despite a tumour size of over 2–3cm, we have suggested surgery to the patient as a full-thickness excision/biopsy, being aware of the difficulties of differentiating benign lesions from severe dysplasias and initial stages of malignancy (T1) using the usual diagnostic tests (endorectal ultrasound and pelvic MRI), principally in large polypoid lesions. Therefore, except for three patients where the tumour involvement had reached muscle, TEO was the correct and sufficient surgery for the remaining patients, as these were lesions with severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ or tumours affecting the mucosa or submucosa (pT1) with no poor prognostic criteria.

With regard to the extent of resection, we had 9.3% insufficient resection margins in the lesions considered benign or T1 and in all of them there were edges with adenomatous dysplasia, which obliged us to reoperate on these patients using TEO.

In conclusion, the TEO technique allowed benign rectal tumours not removable endoscopically to be resected, with a low morbidity rate. It allows curative treatment of malignant rectal neoplasias which have been confirmed histologically as pT1 carcinomas. In line with these observations, histological diagnosis and preoperative staging are essential for careful selection of these patients. It could offer the potential benefit of a minimally invasive approach, but without the risks associated with abdominal rectal surgery. Furthermore, the analysis of this consecutive series of patients operated with TEO suggests that the technique is safe and effective in the treatment of adenomas and pT1 carcinomas, with recurrence comparable to that of conventional surgery.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gavilanes Calvo C, Manuel Palazuelos JC, Alonso Martín J, Castillo Diego J, Martín Parra I, Gómez Ruiz M, et al. Cirugía endoscópica transanal en tumores rectales. Cir Esp. 2014;92:38–43.