Cystic lymphangioma (CL) is a benign malformation of the lymphatic system, consequence of a failed connection between the lymphatic vessels and the venous system during embryonic development. It is usually diagnosed in infancy, before the age of 2.

The most frequent locations of this pathology are the neck (75%), axillae (20%) or the lateral trunk, although CL may also appear in the mediastinum or retroperitoneum (1%).1

During their growth, masses form that can reach a large size, infiltrate adjacent tissue, show malignant behavior and even affect vital organs, putting the patient's life at risk. Complete exeresis of the lesion is therefore quite difficult.2

The treatment of choice is surgical excision to avoid superinfection, rapid growth, risk of rupture or emergency laparotomy.3 Although surgery is the treatment of choice, in many cases complete removal of the CL is not achieved, especially when large vessels and/or nerves are surrounded, due to the high risk for injuring these structures. Postoperative complication rates range from 12 to 33%.4

One therapeutic option is sclerosis with an injection of Picibanil® (OK-432), after which several studies have reported total tumor remission, both cervical as well as retroperitoneal.5 Ogita et al. published the first study of lymphangiomas treated with Picibanil®, demonstrating the sclerosing effect and reduction in lesion size.6

Picibanil® is a lyophilized preparation of a low-virulence strain, extracted from group A Streptococcus pyogenes of human origin and incubated in penicillin-G, that incapacitates the production of streptolysin S. Its injection causes local inflammation in the perilesional area, without affecting the skin or leaving scars, which is important because it does not contraindicate surgery if Picibanil® is ineffective. This local reaction is especially relevant in CL that are close to the airway because of the possibility to cause obstruction.4 The most common adverse reaction is low-grade fever for some days, which responds to antipyretics; pain is another possible side effect.2 Cases have been described of anemia requiring transfusion, as well as transient increase in platelet count with spontaneous resolution.7

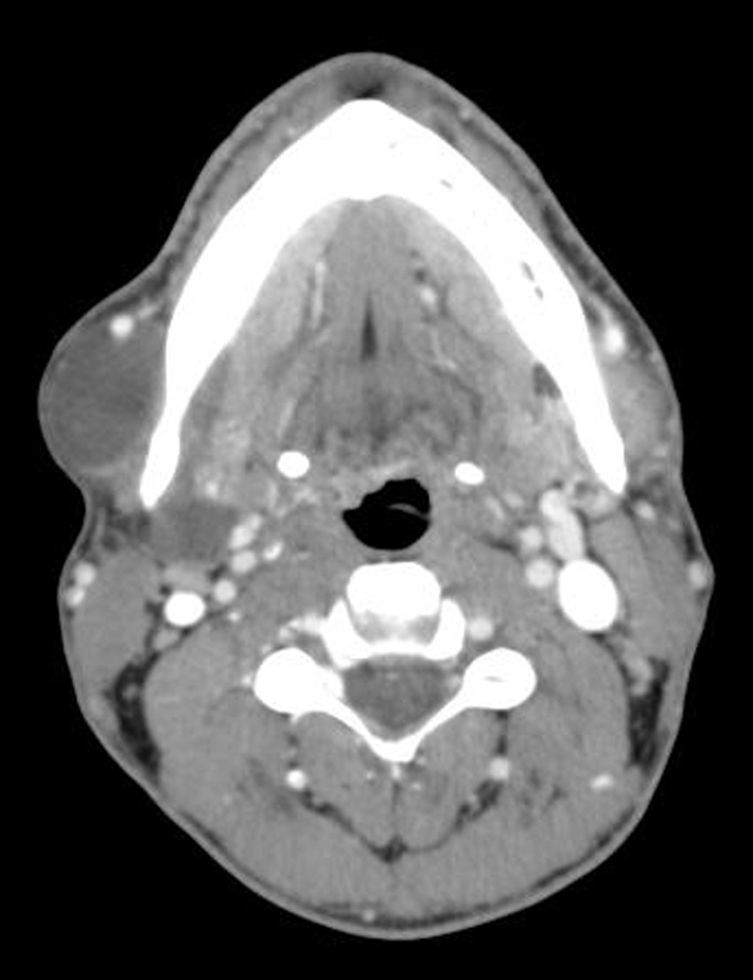

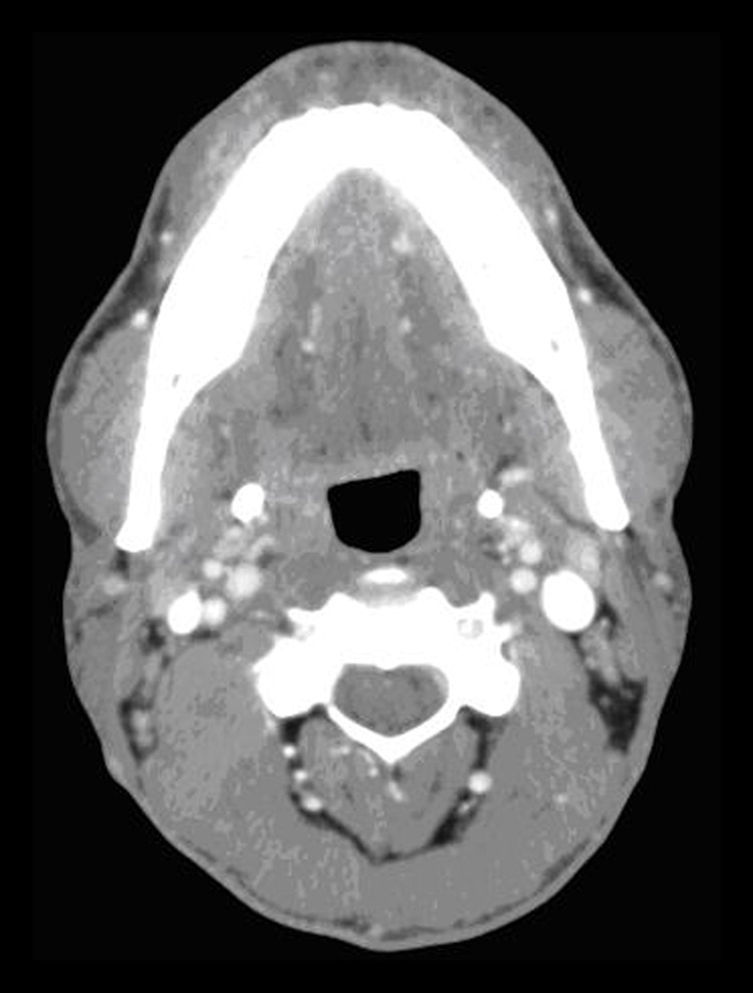

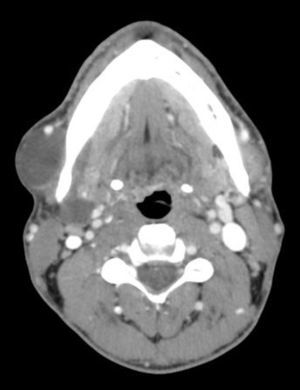

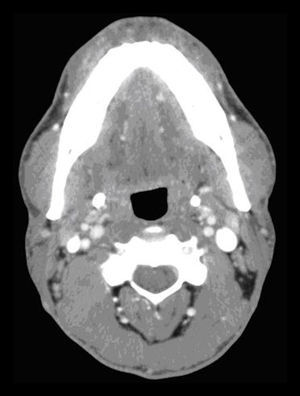

We retrospectively analyzed 13 patients with CL at our hospital between January 2009 and December 2014. Three were treated with Picibanil® injection. All patients underwent imaging studies (Fig. 1) prior to surgery and FNA of the lesion. All signed informed consent specifically for sclerosis with Picibanil®. The procedures were done under radiological guidance.

After needle puncture, the content was aspirated, obtaining more than 20ml of cystic fluid. Afterwards, 20ml of saline were injected with 0.2mg of Picibanil®. The quantity to be injected depends on the tumor size, but the total amount should not surpass 20ml. It is important to conduct the infusion as slowly as possible to avoid pain.6 After the treatment, it is important to keep in mind the possible appearance of hypersensitivity symptoms, such as fever, erythema, tumefaction or pain in the area of the lesion.

The series includes 3 patients (2 women and 1 male) with a mean age of 45 (range: 41–48 years). The locations of the lymphangiomas were bilateral submaxillary, right cervical and retroperitoneal. The latter was treated surgically and considered unresectable as it infiltrated vertebral bodies and the inferior cava, so we therefore decided to use treatment with Picibanil®. No complications were observed after the injection.

In cervical CL, the follow-up was weekly. In the first week, the tumor increased, to later decrease progressively until its complete disappearance 2 months after the injection with Picibanil®. Afterwards, follow-up visits were every 3 months and, annually at present.

In the submaxillary CL, the left component disappeared after a second injection administered one year after the first. This patient has been evaluated monthly, and 3 scleroses with Picibanil® were done on the right component, achieving complete resolution after the last sclerosis (Fig. 2).

In the retroperitoneal CL, no clinical or radiological improvements were observed. Currently, the patient has chronic abdominal pain, probably related with the inflammatory reaction of the injection.

The non-surgical management of CL is controversial due to the risk for complications and recurrences. Picibanil® injections can be considered a therapeutic alternative to surgery, especially in the cervical region, with the advantage of avoiding injury to vascular or nervous structures. Several studies demonstrate the effectiveness of Picibanil® as a treatment of choice for CL, particularly of cervical presentations, in pediatric patients.7,8 It has been demonstrated that Picibanil® is safe and effective for the treatment of CL in children, with complete resolution of the lesion in 92% of cases.2

In retroperitoneal CL, this technique can be combined with surgery to minimize the associated risks. The literature describes some cases of complete resolution even after a single Picibanil® injection.5

If the lesion does not become reduced 3–6 weeks after the first injection, some authors recommend a second injection prior to surgical treatment. It is accepted that, if the treatment is not effective after 3 injections with an interval of 12 weeks between them, surgery is indicated.9 Studies have compared this therapy with bleomycin and have not demonstrated superior effects to Picibanil®.10

In spite of the limitations of our series, the results indicate that Picibanil® is useful as an initial therapy in selected cases. When complete resolution of the lesion is not achieved, a combined treatment of Picibanil® injection and later surgery could be used.

AuthorshipStudy design, data collection and composition of the article: Delia María Luján Martínez.

Analysis/interpretation of the results and composition of the article: Mari Fe Candel Arenas.

Data collection and analysis/interpretation of the results: Miguel Ruiz Marín.

Study design and interpretation of the results: Pedro Antonio Parra Baños.

Study design, critical review and approval of the final version: Antonio Albarracín Marín-Blázquez.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Luján Martínez DM, Candel Arenas MF, Ruiz Marín M, Parra Baños PA, Albarracín Marín-Blázquez A. Utilidad del tratamiento conservador en el linfangioma quístico. Cir Esp. 2016;94:485–487.