To identify the association of diabetes education or medical nutrition therapy with the goals of control of cardiovascular risk indicators and dietary habits in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Material and methodsAnalytical cross-sectional study in 395 primary care patients. HbA1c, fasting glucose and lipid profile, blood pressure, weight, waist circumference, and body composition were measured. Dietary habits were measured using the “Instrument for measuring lifestyle in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus” (IMEVID), in the nutrition dimension. Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and diabetes education (DE) were considered as received by the patient when provided in their healthcare clinic.

ResultsWomen comprised 68% of the patients, with a median of 6 years from diabetes diagnosis. Of the patients, 21% received DE and MNT, 28% DE or MNT, and 51% received neither. The HbA1c was lower in the patients with DE and MNT (7.7% ± 1.9% vs. 8.7% ± 2.3%, 8.4% ± 2.2%; p = 0.003) respectively. In the patients with DE and MNT, a higher proportion took physical exercise, consumed less tobacco, and had better dietary habits (p < 0.05). Patients who received DE and MNT achieved HbA1c and HDL-c control levels. A greater risk of HbA1c > 7% was identified when they only received DE or MNT or neither, a longer time since diagnosis of the disease and less frequent adherence to a diet to control the disease (p < 0.05).

ConclusionDiabetes education and medical nutritional therapy favour the goal of cardiovascular risk control and better dietary habits in the patient with type 2 diabetes.

Identificar la asociación de la educación en diabetes y terapia médica en nutrición con metas de control de indicadores de riesgo cardiovascular y hábitos dietéticos en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal analítico en 395 pacientes de atención primaria. Se realizaron mediciones de HbA1c, glucosa y perfil de lípidos en ayuno, presión arterial, peso, circunferencia de cintura y composición corporal. Los hábitos dietéticos se midieron a través del «Instrumento para medir el estilo de vida en los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2» (IMEVID), en la dimensión nutrición. La terapia médica nutricional (TMN) y la educación en diabetes (ED), se consideró como recibida por el paciente cuando esta fue otorgada en su clínica de atención.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 68% mujeres, con una mediana de seis años de diagnóstico de diabetes. Recibieron ED y TMN un 21%, solo ED o TMN 28% y 51% ninguna de ellas. La HbA1c fue menor en pacientes con ED y TMN (7,7 ± 1,9% vs. 8,7 ± 2,3%, 8,4 ± 2,2%; p = 0,003), respectivamente. En pacientes con ED y TMN hubo una mayor proporción que realizó ejercicio físico, menor consumo de tabaco, mejores hábitos dietéticos (p < 0,05). Los pacientes que recibieron ED y TMN alcanzaron metas de control de la HbA1c y HDL-c. Mostraron mayor riesgo de tener una HbA1c > 7% cuando solo recibieron ED o TMN o ninguna de ellas, mayor tiempo de diagnóstico de la enfermedad y seguir con menor frecuencia una dieta para el control de la enfermedad (p < 0,05).

ConclusiónLa educación en diabetes y la terapia médica nutricional favorecen las metas de control de riesgo cardiovascular y mejores hábitos dietéticos del paciente con diabetes tipo 2.

It is estimated that by the year 2035 600 million individuals worldwide will have type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 In Mexico, the reported prevalence of diabetes in 2016 was 13.7%, of which 30% were not aware of their disease.2 The main aim in managing diabetes is to achieve metabolic control that gives patients an acceptable quality of life, while also reducing or preventing micro- and macro-vascular complications. To achieve this the American Diabetes Association guidelines recommend, as part of the non-pharmacological treatment, providing education about the disease, medical nutrition therapy, regular physical exercise, suspending or ceasing smoking and psychological help.3

The goal of holistic treatment is to achieve and maintain a glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level < 7%, fasting glucose from 80 mg/dL to 130 mg/dL and peak post-prandial glucose lower than 180 mg/dL.4 The aim is also to achieve arterial blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg, with appropriate lipid profile levels and the prevention and/or reduction in obesity.5

Unfortunately, in Mexico only 36.7% of men and 28.7% of women with diabetes have HbA1c < 7%.2 Achievement of the control goals has been reported in 40% for HbA1c, 44% for low density cholesterol (LDL-c), 46% for high density cholesterol (HDL-c), 40% for triglycerides and 51% in arterial blood pressure levels.6 In the U.S.A., control of HbA1c is achieved in 56% of cases, arterial blood pressure in 51% and 49% of LDL-c,7 while in Germany the corresponding figures are 79%, 56% and 34%, respectively.8

In Mexico it has been reported that a healthy diet is associated with low levels of HbA1c.9 A high fibre content in the diet reduces HbA1c and triglyceride levels and increases HDL-c levels.10 Studies which centre on the effect of diet and education in diabetes have shown them to be effective in improving cardiovascular indicators in patients with type 2 diabetes.11,12 Although medical nutritional therapy and education have been shown to be effective in diabetes for the control of certain disease indicators, in Mexico it is still the case that a low proportion of patients with diabetes receive education about the condition (9.3%), and moreover 46% do not implement preventive measures against complications caused by the disease.13 There is also less information about the effect of strategies of this type in modifying dietary habits and achieving control goals for cardiovascular risk indicators. Due to the above considerations, the purpose of this study was to identify the association of education about diabetes and medical nutritional therapy with dietary habit goals and control goals for cardiovascular risk indicators in primary care patients with type 2 diabetes.

Material and methodsAn analytical cross-sectional study was performed of patients in four family medicine clinics of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), in Mexico City, in the period from January 2017 to September 2018. This research was approved by the committee of IMSS Hospital General de Zona No 1 “Carlos MacGregor Sánchez Navarro”, with registration number R-2019-3609-028. The patients were invited to take part in the study when they visited for their check-ups, after they had received an explanation of the study purpose and their doubts had been resolved, and they voluntarily signed the informed consent document. The participants subsequently visited the Research Unit, where measurements were taken.

The sample size was calculated by using the formula for the different proportions of patients who received MNT and DE to achieve control of HbA1c (<7%) in 30% as reported previously, in comparison with 15% of patients without MNT or DE or any intervention at all.14 Considering a 95% confidence level, a power of 90% and a ratio between the sample size of one, the sample size calculated stands at 322 patients. This study included 395 participants.

Participant selection criteriaPatients with type 2 diabetes were included, having been diagnosed by their doctor and who visited a primary care clinic. They were ≤70 years old and their diabetes had evolved over less than 20 years, and they were at least able to read and write. Patients with advanced complications of the disease were excluded, such as peripheral neuropathy, blindness, advanced renal disease (in dialysis or haemodialysis). Pregnant women were also excluded.

Sociodemographic and clinical variablesSociodemographic data and clinical histories were obtained by a medical researcher. Patients were classified as having been diagnosed with systemic arterial hypertension (SAH) when their doctor had done so. The diagnosis of SAH was also applied when their systolic or diastolic arterial blood pressure measured during the medical examination in the study was ≥140/90 mmHg, respectively, on more than two occasions.15 Arterial blood pressure was measured twice in the left arm with a mercury sphygmomanometer, with a time lapse of five minutes between each measurement. Patients were classified as undertaking regular physical exercise when they stated that they performed moderate aerobic exercise during at least 150 min per week, distributed over at least three days of the week.16

Anthropometric and body composition variablesAnthropometric parameters were recorded by two qualified nutritionists. They followed the standardization method proposed by Habicht and the specifications for taking measurements recommended by Lohman et al.17,18

Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the mid-point between the lowest rib and the upper edge of the right iliac crest. It was measured three times, and the average of the second and third measurements were used for analysis. Fat percentage was measured using the lower limb bioimpedence method, with a TANITA™ TBF-215 body composition analyser (Tanita Corporation of America Inc. South Clearbrook Drive Arlington Heights, Illinois, U.S.A.).

Biochemical variablesHbA1c was determined in venous blood after fasting for 12 h, using the high resolution liquid chromatography method. Glucose, creatinine, triglycerides, total cholesterol and the HDL-c and LDL-c fractions were measured using the automated photometry technique (Roche Diagnostics Asia Pacific Pte Ltd., Roche Cobas 800 c701).

Metabolic control goalsMetabolic control goals were set at figures of <7% HbA1c, <130 mg/dL fasting glucose, <200 mg/dL total cholesterol, >40 HDL cholesterol in men and >50 mg/dL in women; <150 mg/dL triglycerides.19 Arterial blood pressure was considered to be controlled with figures <140/90 mm Hg. Waist circumference was considered to be controlled when it was <80 cm in women and <90 cm in men.20

Medical nutritional therapyPatients were considered to have received MNT when they visited the nutritionist to receive care, at least twice during the year prior to the study.

Dietary habitsInformation about dietary habits (the consumption of vegetables, fruit, bread and tortilla per day, sugar and salt consumption, as well as the consumption of other foods) was obtained using the validated instrument denominated the “Instrument for measuring lifestyle in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus” (LMIDM), which is shown in Appendix B Annex 1. This instrument was supplied to all of the patients, who were then allowed to answer it personally, without the intervention of any medical staff.21

Diabetes educationPatients were considered to have received education about diabetes (DE) when they stated that they had attended the “DiabetIMSS” course offered in primary care clinics at least six times during the previous year.22 This programme consists of one session a month during one year.

Statistical analysisMeasurements of frequencies and proportions were calculated, together with central tendency and dispersion measures to characterize sociodemographic, dietary and clinical variables.

The χ2 test was used to compare three groups, composed of: a) those who received diabetes education and medical nutritional therapy (DE and MNT); b) those who received one of these measures (DE or MNT); c) patients who received neither type of intervention (no DE and no MNT). The three groups were compared in terms of their sociodemographic and clinical variables, as well as the cardiovascular risk goals and their dietary habits.

The single factor Anova test was used to make comparisons between cardiovascular risk factors in the three above-mentioned groups. Given that they did not have a parametric distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the number of years since diagnosis of the disease and fasting glucose and triglyceride levels.

A multiple logistic regression model was created to calculate the risk of having HbA1c > 7%, associated with the variables of age, sex, years since diagnosis of diabetes, DE and MNT intervention in their clinic and following a diet to control the disease. To measure association the odds ratio (OR) was calculated, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for all of the variables included in the model.

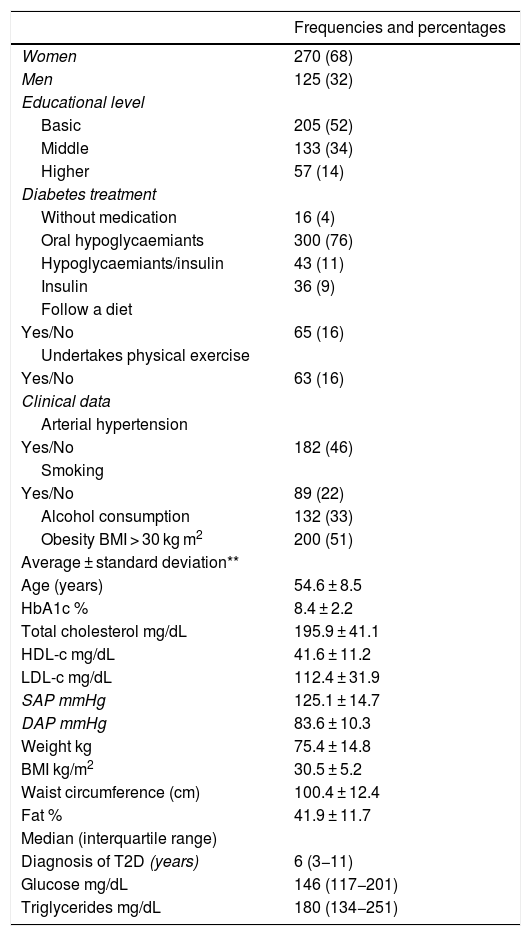

ResultsTable 1 shows the distribution of the sociodemographic, clinical and anthropometric data of the total population of the sample. A higher proportion of women were included, at 68%. The average age was 54.6 ± 8,5 years and the median number of years after the diagnosis of diabetes was six years. The average HbA1c level was 8.4 ± 2.2, and the most frequent diabetes treatment used were oral hypoglycaemiant medications. Only 16% followed a diet and undertook physical exercise, and 51% of the population studied were obese.

Sociodemographic, clinical and anthropometric data in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, n = 395.

| Frequencies and percentages | |

|---|---|

| Women | 270 (68) |

| Men | 125 (32) |

| Educational level | |

| Basic | 205 (52) |

| Middle | 133 (34) |

| Higher | 57 (14) |

| Diabetes treatment | |

| Without medication | 16 (4) |

| Oral hypoglycaemiants | 300 (76) |

| Hypoglycaemiants/insulin | 43 (11) |

| Insulin | 36 (9) |

| Follow a diet | |

| Yes/No | 65 (16) |

| Undertakes physical exercise | |

| Yes/No | 63 (16) |

| Clinical data | |

| Arterial hypertension | |

| Yes/No | 182 (46) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes/No | 89 (22) |

| Alcohol consumption | 132 (33) |

| Obesity BMI > 30 kg m2 | 200 (51) |

| Average ± standard deviation** | |

| Age (years) | 54.6 ± 8.5 |

| HbA1c % | 8.4 ± 2.2 |

| Total cholesterol mg/dL | 195.9 ± 41.1 |

| HDL-c mg/dL | 41.6 ± 11.2 |

| LDL-c mg/dL | 112.4 ± 31.9 |

| SAP mmHg | 125.1 ± 14.7 |

| DAP mmHg | 83.6 ± 10.3 |

| Weight kg | 75.4 ± 14.8 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 30.5 ± 5.2 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.4 ± 12.4 |

| Fat % | 41.9 ± 11.7 |

| Median (interquartile range) | |

| Diagnosis of T2D (years) | 6 (3−11) |

| Glucose mg/dL | 146 (117−201) |

| Triglycerides mg/dL | 180 (134−251) |

BMI: body mass index; DAP: diastolic arterial pressure; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL-c: high density cholesterol; LDL-c: low density cholesterol; SAP: systolic arterial pressure; T2D: type 2 diabetes.

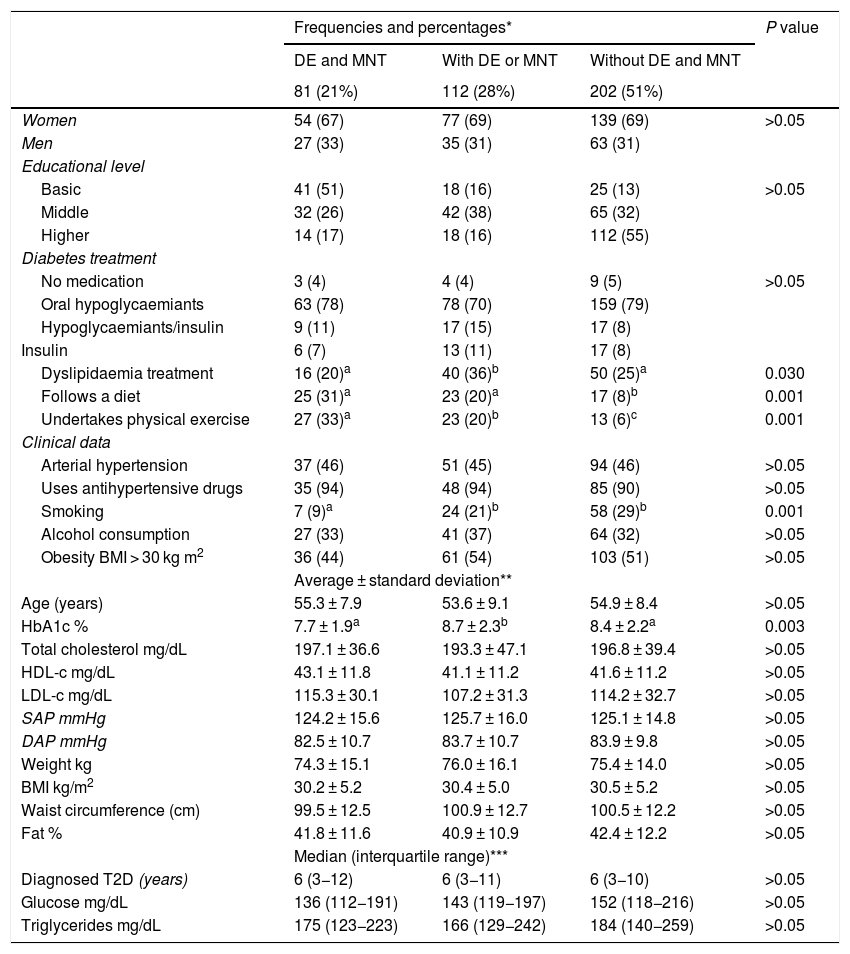

Of the total number of 395 patients studied, 21% had received DE and MNT, 28% had received one of these interventions and 51% had not received either of them. HbA1c levels were lower in the group with DE and MNT in comparison with the group that had received only one of the interventions or those who had not received any intervention (P = 0.003). There was a difference between the groups who followed a treatment for dyslipidaemia, and the level was lower in the group with DE and MNT (P = 0.030). The group that had received both interventions was found to contain a higher proportion of patients who followed a diet or undertook physical exercise, together with fewer smokers (P = 0.001). These data are shown in Table 2.

Sociodemographic, clinical and anthropometric data in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, n = 395.

| Frequencies and percentages* | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE and MNT | With DE or MNT | Without DE and MNT | ||

| 81 (21%) | 112 (28%) | 202 (51%) | ||

| Women | 54 (67) | 77 (69) | 139 (69) | >0.05 |

| Men | 27 (33) | 35 (31) | 63 (31) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Basic | 41 (51) | 18 (16) | 25 (13) | >0.05 |

| Middle | 32 (26) | 42 (38) | 65 (32) | |

| Higher | 14 (17) | 18 (16) | 112 (55) | |

| Diabetes treatment | ||||

| No medication | 3 (4) | 4 (4) | 9 (5) | >0.05 |

| Oral hypoglycaemiants | 63 (78) | 78 (70) | 159 (79) | |

| Hypoglycaemiants/insulin | 9 (11) | 17 (15) | 17 (8) | |

| Insulin | 6 (7) | 13 (11) | 17 (8) | |

| Dyslipidaemia treatment | 16 (20)a | 40 (36)b | 50 (25)a | 0.030 |

| Follows a diet | 25 (31)a | 23 (20)a | 17 (8)b | 0.001 |

| Undertakes physical exercise | 27 (33)a | 23 (20)b | 13 (6)c | 0.001 |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 37 (46) | 51 (45) | 94 (46) | >0.05 |

| Uses antihypertensive drugs | 35 (94) | 48 (94) | 85 (90) | >0.05 |

| Smoking | 7 (9)a | 24 (21)b | 58 (29)b | 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 27 (33) | 41 (37) | 64 (32) | >0.05 |

| Obesity BMI > 30 kg m2 | 36 (44) | 61 (54) | 103 (51) | >0.05 |

| Average ± standard deviation** | ||||

| Age (years) | 55.3 ± 7.9 | 53.6 ± 9.1 | 54.9 ± 8.4 | >0.05 |

| HbA1c % | 7.7 ± 1.9a | 8.7 ± 2.3b | 8.4 ± 2.2a | 0.003 |

| Total cholesterol mg/dL | 197.1 ± 36.6 | 193.3 ± 47.1 | 196.8 ± 39.4 | >0.05 |

| HDL-c mg/dL | 43.1 ± 11.8 | 41.1 ± 11.2 | 41.6 ± 11.2 | >0.05 |

| LDL-c mg/dL | 115.3 ± 30.1 | 107.2 ± 31.3 | 114.2 ± 32.7 | >0.05 |

| SAP mmHg | 124.2 ± 15.6 | 125.7 ± 16.0 | 125.1 ± 14.8 | >0.05 |

| DAP mmHg | 82.5 ± 10.7 | 83.7 ± 10.7 | 83.9 ± 9.8 | >0.05 |

| Weight kg | 74.3 ± 15.1 | 76.0 ± 16.1 | 75.4 ± 14.0 | >0.05 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 30.2 ± 5.2 | 30.4 ± 5.0 | 30.5 ± 5.2 | >0.05 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 99.5 ± 12.5 | 100.9 ± 12.7 | 100.5 ± 12.2 | >0.05 |

| Fat % | 41.8 ± 11.6 | 40.9 ± 10.9 | 42.4 ± 12.2 | >0.05 |

| Median (interquartile range)*** | ||||

| Diagnosed T2D (years) | 6 (3−12) | 6 (3−11) | 6 (3−10) | >0.05 |

| Glucose mg/dL | 136 (112−191) | 143 (119−197) | 152 (118−216) | >0.05 |

| Triglycerides mg/dL | 175 (123−223) | 166 (129−242) | 184 (140−259) | >0.05 |

BMI: body mass index; DAP: diastolic arterial pressure; DE: diabetes education; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL-c: high density cholesterol; LDL-c: low density cholesterol; MNT: medical nutrition therapy; SAP: systolic arterial pressure; T2D: type 2 diabetes.

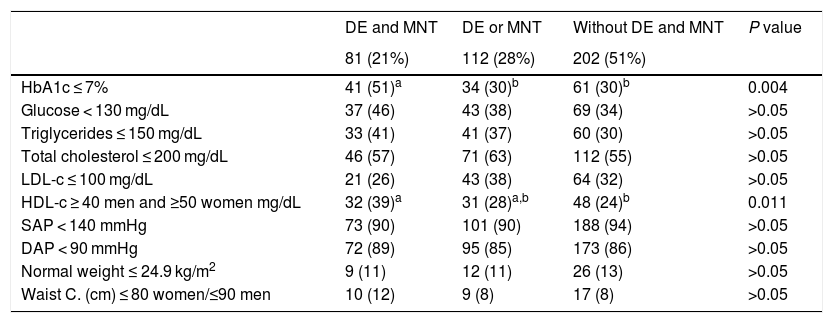

Table 3 shows that the highest proportion of patients with HbA1c at control goal levels were in the group of patients with DE and MNT in comparison with the other groups (P = 0.004), as well as a higher proportion of subjects with favourable levels of HDL-c (P = 0.011). When triglyceride levels <150 mg/dL were compared, a difference close to statistical significance was found (P = 0.06).

Comparison of the metabolic control goals in association with nutritional therapy and diabetes education in the patients studied, n = 395.

| DE and MNT | DE or MNT | Without DE and MNT | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81 (21%) | 112 (28%) | 202 (51%) | ||

| HbA1c ≤ 7% | 41 (51)a | 34 (30)b | 61 (30)b | 0.004 |

| Glucose < 130 mg/dL | 37 (46) | 43 (38) | 69 (34) | >0.05 |

| Triglycerides ≤ 150 mg/dL | 33 (41) | 41 (37) | 60 (30) | >0.05 |

| Total cholesterol ≤ 200 mg/dL | 46 (57) | 71 (63) | 112 (55) | >0.05 |

| LDL-c ≤ 100 mg/dL | 21 (26) | 43 (38) | 64 (32) | >0.05 |

| HDL-c ≥ 40 men and ≥50 women mg/dL | 32 (39)a | 31 (28)a,b | 48 (24)b | 0.011 |

| SAP < 140 mmHg | 73 (90) | 101 (90) | 188 (94) | >0.05 |

| DAP < 90 mmHg | 72 (89) | 95 (85) | 173 (86) | >0.05 |

| Normal weight ≤ 24.9 kg/m2 | 9 (11) | 12 (11) | 26 (13) | >0.05 |

| Waist C. (cm) ≤ 80 women/≤90 men | 10 (12) | 9 (8) | 17 (8) | >0.05 |

BMI: body mass index; DAP: diastolic arterial pressure; DE: diabetes education; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HDL-c: high density cholesterol; LDL-c: low density cholesterol; MNT: medical nutrition therapy; SAP: systolic arterial pressure.

χ2 test.

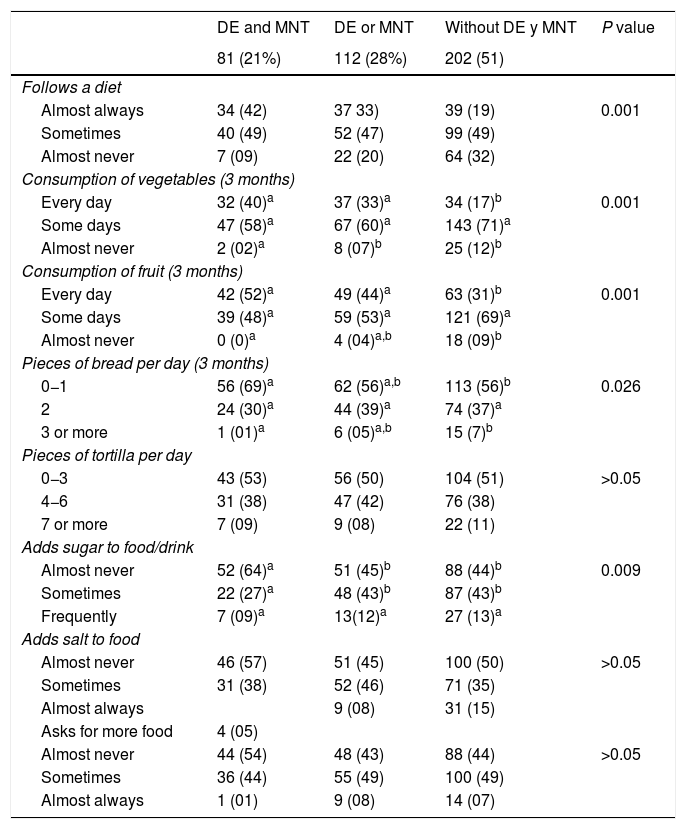

Dietary habit data are shown in Table 4, where a higher proportion of patients were found to follow a diet among those who received DE + MNT (P = 0.001), with a higher consumption of vegetables (P = 0.001), as well as fruit (P = 0.001), and lower consumption of bread (P = 0.03). The group who had received DE + MNT added sugar to foods and/or drinks less often (P = 0.009).

Dietary habit in the last three months in association with MNT and DE in the patients with type 2 diabetes, n = 395.

| DE and MNT | DE or MNT | Without DE y MNT | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81 (21%) | 112 (28%) | 202 (51) | ||

| Follows a diet | ||||

| Almost always | 34 (42) | 37 33) | 39 (19) | 0.001 |

| Sometimes | 40 (49) | 52 (47) | 99 (49) | |

| Almost never | 7 (09) | 22 (20) | 64 (32) | |

| Consumption of vegetables (3 months) | ||||

| Every day | 32 (40)a | 37 (33)a | 34 (17)b | 0.001 |

| Some days | 47 (58)a | 67 (60)a | 143 (71)a | |

| Almost never | 2 (02)a | 8 (07)b | 25 (12)b | |

| Consumption of fruit (3 months) | ||||

| Every day | 42 (52)a | 49 (44)a | 63 (31)b | 0.001 |

| Some days | 39 (48)a | 59 (53)a | 121 (69)a | |

| Almost never | 0 (0)a | 4 (04)a,b | 18 (09)b | |

| Pieces of bread per day (3 months) | ||||

| 0−1 | 56 (69)a | 62 (56)a,b | 113 (56)b | 0.026 |

| 2 | 24 (30)a | 44 (39)a | 74 (37)a | |

| 3 or more | 1 (01)a | 6 (05)a,b | 15 (7)b | |

| Pieces of tortilla per day | ||||

| 0−3 | 43 (53) | 56 (50) | 104 (51) | >0.05 |

| 4−6 | 31 (38) | 47 (42) | 76 (38) | |

| 7 or more | 7 (09) | 9 (08) | 22 (11) | |

| Adds sugar to food/drink | ||||

| Almost never | 52 (64)a | 51 (45)b | 88 (44)b | 0.009 |

| Sometimes | 22 (27)a | 48 (43)b | 87 (43)b | |

| Frequently | 7 (09)a | 13(12)a | 27 (13)a | |

| Adds salt to food | ||||

| Almost never | 46 (57) | 51 (45) | 100 (50) | >0.05 |

| Sometimes | 31 (38) | 52 (46) | 71 (35) | |

| Almost always | 9 (08) | 31 (15) | ||

| Asks for more food | 4 (05) | |||

| Almost never | 44 (54) | 48 (43) | 88 (44) | >0.05 |

| Sometimes | 36 (44) | 55 (49) | 100 (49) | |

| Almost always | 1 (01) | 9 (08) | 14 (07) | |

DE: diabetes education; MNT: medical nutrition therapy.

χ2 test.

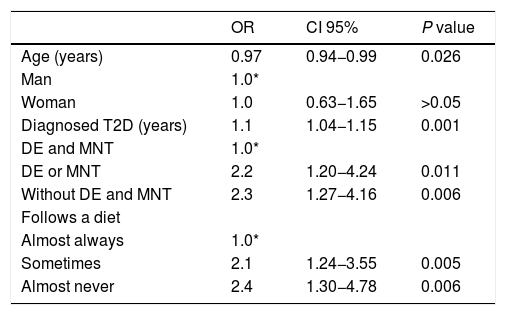

The multivariate analysis shown in Table 5 indicates that the risk of having uncontrolled glycaemia (HbA1c > 7%) increases by 10% for each year after diagnosis of the disease (OR = 1.1; CI 95%: 1.04−1.15). A lack of DE and MNT is associated with double the risk of lack of control (OR = 2.3; CI 95%: 1.27−4.16), similar to that of having deficient dietary behaviour (OR = 2.1; CI 95%: 1.24−3.55) or poor dietary behaviour (OR = 2.4; CI 95%: 1.30−4.78).

Multiple logistic regression model to identify the association between lack of control of glycaemia (HbA1c > 7%) and clinical variables, diabetes education and nutritional therapy, n = 395.

| OR | CI 95% | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.97 | 0.94−0.99 | 0.026 |

| Man | 1.0* | ||

| Woman | 1.0 | 0.63−1.65 | >0.05 |

| Diagnosed T2D (years) | 1.1 | 1.04−1.15 | 0.001 |

| DE and MNT | 1.0* | ||

| DE or MNT | 2.2 | 1.20−4.24 | 0.011 |

| Without DE and MNT | 2.3 | 1.27−4.16 | 0.006 |

| Follows a diet | |||

| Almost always | 1.0* | ||

| Sometimes | 2.1 | 1.24−3.55 | 0.005 |

| Almost never | 2.4 | 1.30−4.78 | 0.006 |

DE: diabetes education; MNT: medical nutrition therapy; OR: odds ratio; CI 95%: 95% confidence interval; T2D: type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is directly associated with cardiovascular disease, and poor control of glycaemia is a direct risk factor for the development of a micro- or macrovascular event. Mortality in general and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes increases when HbA1c ≥ 7%.23 Strict control of HbA1c reduces the incidence of myocardial infarct by 9% and the incidence of cardiovascular events by 7%.24 Nevertheless, a HbA1c level < 6% is also associated with higher mortality, above all in older adult patients.25

To achieve cardiovascular risk indicator control goals it is necessary to intervene with pharmacological treatment and strategies to improve patient self-care and lifestyle.19 According to the results of this study, patients who have not received DE and MNT are at higher risk of lack of control of HbA1c. MNT was found to be beneficial for glycaemic control by reducing HbA1c by up to 2%, while also emphasising follow-up time and personalised advice.26,27 Even so, health interventions should consider instability as well as single levels of HbA1c, given that the former is associated with increased hospitalization, mortality and deterioration of renal function.28

A higher proportion of patients who had received DE and MNT (21%) were found to undertake physical exercise and to smoke less. Physical exercise reduces cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes and metabolic syndrome.29,30 The proportion of patients who do physical exercise is still low (16%), favouring the high frequency of excess weight and obesity in the population. Obesity is a cardiovascular risk factor for metabolic syndrome and mortality in general.31 51% of the patients in this study were obese and received no treatment in terms of diet or education about diabetes. It is important to underline the benefit of this type of non-pharmacological strategies for early intervention to reduce obesity, given that it is one of the main factors that cause mortality in patients with diabetes.32,33

In the Mexican population it has been observed that the combination of high levels of triglycerides, smoking and central obesity are predictors of renal damage in patients with diabetes.34 Isolated interventions are therefore less effective in improving weight and cardiometabolic indicators, so that holistic strategies are necessary for the patient to acquire skills in caring for their disease and adopting a healthy lifestyle.35

Diabetes and metabolic syndrome have both been reported to be common in the rural population in Mexico, and the low level of education there also has negative influence.36 Additionally, this study found that a small proportion of patients receive DE and MNT. It is necessary to insist that the findings underline the importance of offering DE and MNT as parts of an integrated campaign to achieve the control goals of cardiovascular protection. Of our findings respecting the lipid profile, it stands out that more patients who received both strategies achieved the HDL-c control targets. Given this, it has been found that controlling LDL-c together with control of HbA1c and arterial blood pressure may be more effective in reducing micro- and macro-vascular complications.37

A higher proportion of better dietary habits were found in patients who had received DE and MNT, underlining their higher consumption of fruit and vegetables, and their lower consumption of carbon hydrates, as well as their adherence to the diet. Although healthy dietary habits have been associated with improved levels of HbA1c and cardiovascular risk indicators, the patients studied still do not fully adhere to a healthy diet, leading to persistent poor control of glycaemia, obesity and dyslipidaemia.9,38 In turn, it was found that the Mediterranean diet is among those which are the most closely associated with better control of glycaemia and lower cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes.39,40

This is one of the first reports on non-pharmacological intervention in the control of glycaemia and dietary habits in a primary care population with diabetes. Similar results were reported in a cohort of patients with diabetes, where adherence to the diet and pharmacological treatment were the factors most strongly associated with control of HbA1c.41

The proportion of patients who attend to receive DE and MNT is still low in primary care clinics in Mexico. A professional nutritionist is necessary, together with effective follow-up programmes to offer education about diabetes and personalized nutritional therapy. Future studies should be performed to quantify the impact of non-pharmacological intervention on the reduction of long-term comorbidity and clinical and cardiovascular events. The limitations of our study include the fact that in 3% of the patients identified as having newly diagnosed arterial hypertension, this was not measured in both arms. If measurements are taken in both arms and a difference >10 mmHg between them is found, then the measurement should be repeated in the arm where the pressure is highest. Moreover, a design limitation is that it is cross-sectional, and this makes it impossible to evaluate the characteristics of the MNT and DE strategy received.

ConclusionsMedical nutritional therapy and education about diabetes are associated with better achievement of cardiovascular protection goals and dietary habits in patients with type 2 diabetes. The proportion of patients who attend to receive the non-pharmacological strategy in primary care remains low, and there is still a high prevalence of uncontrolled glycaemia and obesity in the population with type 2 diabetes. Strategies should be drawn up to make wider access possible to non-pharmacological therapeutic intervention.

FinancingThis was granted by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), Mexico, through the Fondo Sectorial de Investigación en Salud y Seguridad Social, with registration number: SALUD-2012-1-181015.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the authorities of the family medicine units of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, in Mexico City, for the facilities that were granted to undertake this research.

Please cite this article as: Velázquez-López L, del Prado PSC, Colín-Ramírez E, Muñoz-Torres AV, la Peña JE. La adherencia al tratamiento no farmacológico se asocia con metas de control cardiovascular y mejores hábitos dietéticos en pacientes mexicanos con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2022;34:144–152.