Fibrates are drugs that reduce triglycerides, elevate high-density lipoproteins, as well as decrease small, dense LDL particles. The results of a study have recently been published by the Cochrane Collaboration on fibrates efficacy and safety in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. This study includes a systematic review and a meta-analysis of 6 studies (16,135 patients) that evaluated the clinical benefits of fibrates compared to placebo use or other lipid-lowering drugs. This review showed evidence of a protective effect of the fibrates compared with placebo as regards a reduction 16% of a compound objective of death due to cardiovascular disease, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal cerebrovascular accident (NNT: 112), and that reduce coronary morbidity and mortality by 21% (NNT: 125). In addition, fibrates could reduce previously established diabetic retinopathy. However, fibrates do not influence total mortality, or non-cardiovascular mortality. Its joint use with statins does not benefit patients without established cardiovascular disease, compared to the use of statins in monotherapy. Fibrates are safe, although they can elevate serum creatinine levels.

Los fibratos son un grupo de hipolipidemiantes que reducen los triglicéridos, elevan las lipoproteínas de alta densidad y disminuyen la fracción de partículas de LDL pequeñas y densas. Recientemente, se han publicado los resultados de un estudio de la Colaboración Cochrane sobre su eficacia y seguridad en la prevención primaria de la enfermedad cardiovascular. Este estudio incluye una revisión sistemática y un metaanálisis de 6 estudios (16.135 pacientes) que evalúan, en personas en prevención primaria, los beneficios clínicos de los fibratos comparados con el uso de un placebo o de otros hipolipidemiantes. Concluyen que, comparados con placebo, los fibratos son útiles para reducir en un 16% el combinado muerte por enfermedad cardiovascular, infarto de miocardio no fatal o accidente cerebrovascular no fatal (NNT: 112) y que disminuyen la morbimortalidad coronaria un 21% (NNT: 125). Complementariamente, los fibratos podrían reducir la retinopatía diabética previamente establecida. Sin embargo, no influyen en la mortalidad total ni en la de origen no cardiovascular. Tampoco su empleo conjunto con estatinas beneficia a pacientes sin enfermedad cardiovascular establecida, comparado con el uso de estatinas en monoterapia. Los fibratos son seguros, aunque pueden elevar los niveles séricos de creatinina.

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the major aetiological lipid factor for the development of arteriosclerosis. However, the finding of elevated serum triglyceride (TG) levels and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) may identify those people who are at further risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) who could benefit from treatment with a modification of said lipids.1,2

In the general population, several underlying causes predetermine the presence of elevated TG and low levels of HDL-C: excess weight and obesity, physical inactivity, smoking, excessive consumption of alcohol, a diet very high in carbohydrates (>60% of total energy), type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, certain drugs (corticosteroids, HIV protease inhibitors, beta-adrenergic blocking agents, oestrogens) and genetic factors.3,4

When TG levels are ≥200mg/dl, the presence of larger quantities of atherogenic remnant lipoproteins may increase the risk of coronary disease substantially beyond what is predicted by the LDL-C concentration.5

In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) identified low levels of HDL-C (<40mg/dl in men; <45mg/dl in women) as the second most important coronary risk factor after LDL-C.6

The so-called atherogenic dyslipidaemia (AD) groups the aforementioned abnormalities: hypertriglyceridaemia, low HDL-C and presence of a high proportion of small, dense LDL particles.7

Fibrates are drugs that induce changes in the gene transcription that controls lipid metabolism and are effective for modifying AD.8–10 Among other actions, they stimulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, which leads to an increase in the production of apolipoproteins that configure HDLs. Additionally, fibrates improve the catabolism of TG, increasing the production of lipoprotein lipase and stimulating cellular uptake of fatty acids and their conversion to acyl-coenzyme A derivatives. Therefore, they could be particularly suitable for preventing cardiovascular events in people with low levels of HDL-C and high TG.2

The fibrates that are currently available include: gemfibrozil, fenofibrate, fenofibric acid, bezafibrate, etofibrate and ciprofibrate. Clofibrate is no longer used due to the excess mortality its use has caused.11,12

Despite their AD-modifying properties, in patients in primary prevention, that is, without history of coronary or cerebrovascular arteriosclerosis, the evidence for fibrates reducing morbidity and mortality associated with CVD or general morbidity and mortality is not clearly defined, and is the object of this systematic review.

Reason for this reviewAs the authors of this review of the Cochrane Collaboration emphasise,13 its importance is established, on the one hand, because in none of the previous systematic examinations and meta-analyses from controlled, randomised trials on fibrates and their effect on CVD are results reported separately in primary or secondary prevention.9,10,14 Furthermore, the main evidence of the clinical benefit comes from controlled trials with placebo, which use long-standing fibrates: such as gemfibrozil, which when used in combination with statins pose a high risk of producing muscle toxicity, so their joint use should be avoided; or clofibrate, which was withdrawn from the market more than 15 years ago for increasing mortality.

A final reason comes from the need to clarify doubts about the additional benefit fibrates offer to those patients taking them alongside statins, as has been raised in the most recent trials: the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD)15 or Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) Study.16

Objectives and methodsThe objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis of the Cochrane Collaboration13 has been to assess, in people in primary prevention, the clinical benefits in terms of CVD morbidity and mortality and the adverse effects both of fibrates compared with the use of a placebo, and the use of fibrates plus other lipid-modifying drugs against other lipid-lowering agents.

The effect on a combination of the major CVA events was assessed as the primary objective: death due to CVA, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal cerebrovascular accident (CVA). The secondary objectives were also assessed: total mortality; non-cardiovascular mortality; diabetic retinopathy (progression of pre-existing diabetic retinopathy and development of new diabetic retinopathy); incidence of albuminuria (incidence of macroalbuminuria and incidence of micro or macroalbuminuria).

The appearance of adverse effects attributable to the use of fibrates was also assessed. Quality of life reported by patients could not be analysed as this factor was not recorded in any of the publications.

6 controlled, randomised studies were included, which used any fibrate other than clofibrate in primary prevention patients – this exclusion being motivated by the withdrawal of this drug from the market – and whose results could be assessed to respond to the established objectives. Data for a total of 16,135 patients was analysed. Three of the studies included primary and secondary prevention patients, but the authors were able to obtain the data from those patients who had not previously presented with CVD separately. Four of these trials were conducted exclusively with diabetic patients. The follow-up period was 2–5 years.

The quality of the tests was assessed with the GRADE system.17

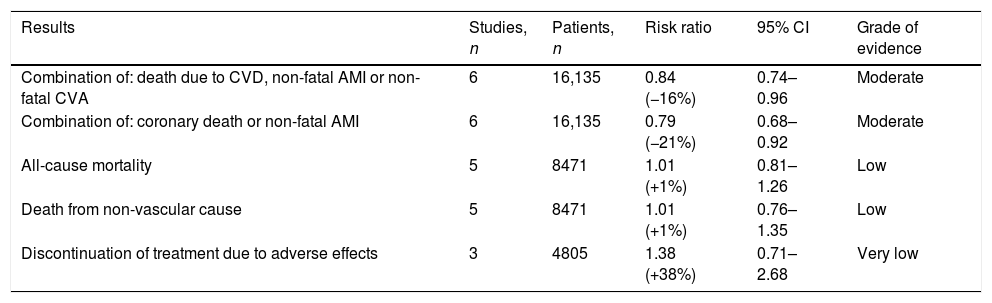

Results (Table 1)Combined result of the major events of cardiovascular disease: death due to cardiovascular disease, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal cerebrovascular accidentFrom the analysis of the 6 studies included in the review, which comprised more than 16,000 individuals, it can be deduced that the use of fibrates is accompanied by a significant risk reduction: RR of 0.84 with 95% CI of 0.74–0.96. The number of patients needed to treat (NNT) for 5 years to avoid an event is estimated at 112.

Clinical effects of fibrates on primary prevention.

| Results | Studies, n | Patients, n | Risk ratio | 95% CI | Grade of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combination of: death due to CVD, non-fatal AMI or non-fatal CVA | 6 | 16,135 | 0.84 (−16%) | 0.74–0.96 | Moderate |

| Combination of: coronary death or non-fatal AMI | 6 | 16,135 | 0.79 (−21%) | 0.68–0.92 | Moderate |

| All-cause mortality | 5 | 8471 | 1.01 (+1%) | 0.81–1.26 | Low |

| Death from non-vascular cause | 5 | 8471 | 1.01 (+1%) | 0.76–1.35 | Low |

| Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse effects | 3 | 4805 | 1.38 (+38%) | 0.71–2.68 | Very low |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CI: confidence interval; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; CVD cardiovascular disease.

The information originating from the 6 clinical trials referred to demonstrates that fibrates reduce coronary disease, the RR being 0.79 and the 95% CI, 0.68–0.92. The estimated NNT is 125 patients.

All-cause mortalityWith data originating from 5 trials and more than 8400 individuals, the meta-analysis of the trials did not show any significant effect of fibrates, with an RR of 1.01 and a 95% CI of 0.91–1.26.

Mortality of non-cardiovascular originOn analysing the data from the 5 trials mentioned above, no significant influence of fibrates was observed, with an RR of 1.01 and a 95% CI of 0.76–1.35.

Diabetic retinopathyNo trial conducted exclusively in primary prevention patients provided data on diabetic retinopathy. However, using the information from 3 studies with 2901 patients free from and with established CVD, the risk of progression of pre-existing diabetic retinopathy decreased significantly in the fibrate group, with an RR of 0.67 and 95% CI of 0.56–0.81.

The analysis of the results from 2 of these trials with 1308 participants revealed that the fibrates decreased new onset diabetic retinopathy with an RR of 0.60 and a 95% CI of 0.17–2.09.

Incidence of albuminuriaOnly the ACCORD study provided results in this respect, demonstrating that fenofibrate does not significantly reduce the incidence of macroalbuminuria (albumin/g creatinine rate ≥300mg) and that of macro or microalbuminuria, with an RR of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.67–1.09) and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.83–1.01), respectively.

Adverse effectsThe majority of the studies did not describe the adverse effects caused by the fibrates in detail, as they were scarce or of mild intensity. To mitigate this situation, the authors assessed data originating from the 3 trials (with 4805 participants) that reported discontinuation of treatment due to undesirable consequences, deducing from their analysis the fact that fibrates have a similar effect to that of placebo, with an RR of 1.38 and a 95% CI of 0.78–2.68.

Assessing the few adverse effects that were broken down, it was concluded that fibrates, compared with placebo:

- -

May increase serum creatinine (3 studies; 4805 participants; RR 1.88 and 95% CI 1.65–2.15).

- -

Does not significantly elevate the incidence of biliary lithiasis (3 studies; 4805 participants; RR: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.68–2.62).

- -

Elevation of the transaminases was only reported in 5 patients, compared to one in the placebo group.

- -

Only one patient developed acute pancreatitis.

Fibrates in monotherapy are effective in reducing the combined primary objective (death due to CVD, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal CVA), as deduced from the analysis of 4 trials with 12,153 participants using only these lipid-lowering agents, resulting in an RR of 0.79 and a 95% CI of 0.68–0.92.

Total mortality did not vary after assessing the 3 studies and 4489 participants with an RR of 1.02 and a 95% CI of 0.68–1.52, if fibrates were used in monotherapy.

The effects of fibrates alongside statins were analysed compared with fibrates in monotherapy, 2 trials with 3982 participants did not demonstrate a significant improvement for the combined primary outcome, with an RR of 0.99 and a 95% CI of 0.78–1.26, no on total mortality, with an RR of 1.01 and a 95% CI of 0.78–1.31.

Final commentsIn view of the meta-analysis carried out, this review allows for 2 statements to be made on the use of fibrates in primary prevention:

First, they are useful for reducing the combination of the major cardiovascular events: death due to CVD, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal CVA (NNT: 112) by 16%, compared to placebo.

Second, fibrates reduce coronary morbidity and mortality by 21% more than the use of a placebo (NNT: 125). In addition, fibrates could reduce previously-established diabetic retinopathy.

This efficacy is associated with how safe they are to use, the only limitation being a possible increase in serum creatinine levels. However, they do not influence total or non-cardiovascular mortality. Nor does their beneficial effect extend, in the majority of patients without established CVD, to joint use with statins, compared with the use of statins in monotherapy.

These results are consistent with previously published results. Thus, in the meta-analysis by Jun et al.,10 which included 18 trials with a total of 45,058 participants, the use of fibrates is associated with a reduction of 10% in RR for major cardiovascular events and 13% for coronary events. However, no benefit was found for decreasing the risk of CVA, total mortality or mortality due to CVD. Other meta-analyses corroborate the decrease of 12–22% in non-fatal coronary events with the use of fibrates,9,13,18 including one carried out exclusively with diabetic patients, which showed a reduction of 21% of non-fatal infarction in this population.19

It is very likely that the beneficial effects of fibrates increase beyond what is provided in this meta-analysis if they are indicated preferentially in patients with AD. In this regard, the Helsinki Heart Study, which used gemfibrozil in primary prevention, demonstrated years ago that the reduction of coronary events (fatal and non-fatal acute myocardial infarction and mortality due to ischaemic heart disease) went from 34% in the general population to 65% in patients with AD.20,21 3 meta-analyses that used data from primary and secondary prevention trials came to the same conclusions.22–24

Regarding the reduction of diabetic retinopathy, the conclusions from the meta-analysis match those provided by the FIELD and ACCORD-Eye studies that used fenofibrate, which was demonstrated as being capable of slowing its progression, independent of glycaemic and lipid control, lengthening the time until the first laser session is required by 30–40%.25,26

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Brea A, Millán J, Ascaso JF, Blasco M, Díaz A, Hernández-Mijares A, et al. Los fibratos en la prevención primaria de la enfermedad cardiovascular. Comentarios a los resultados de una revisión sistemática de la Colaboración Cochrane. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2018;30:188–192.