Obesity prevalence has presented an exponential increase in the last decades, becoming a first order public health issue. Dyslipidemia of obesity, characterised by low levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia and small and dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, is partly responsible for the high residual cardiovascular risk of this clinical situation.

On the other hand, bariatric surgery (BS) is the most effective treatment for obesity, obtaining a greater weight loss than achieved with conventional medical therapy and favouring the improvement or remission of associated comorbidities. The most commonly used BS techniques nowadays are laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Both of these procedures have obtained similar results in terms of weight loss and comorbidity remission such as type 2 diabetes mellitus or hypertension.

A differential feature between both techniques could be the different impact on the lipoprotein profile. In this respect, previous studies with short and mid-term follow-up have proved LRYGB to be superior to LSG in total and LDL cholesterol reduction. Results regarding triglycerides and HDL cholesterol are contradictory. Therefore, we consider of interest to review the effects of BS at short and mid-term follow-up on lipoprotein profile, as well as the remission rates of the different lipid abnormalities and the possible related factors.

La prevalencia de la obesidad ha aumentado de manera exponencial en las últimas décadas, convirtiéndose en un problema de salud pública de primer orden. La dislipemia de la obesidad, caracterizada por niveles bajos de colesterol de las lipoproteínas de alta densidad (HDL), hipertrigliceridemia y partículas pequeñas y densas de lipoproteínas de baja densidad (LDL), es responsable en parte del elevado riesgo cardiovascular residual de esta situación clínica.

Por otro lado, la cirugía bariátrica (CB) es el tratamiento más eficaz para la obesidad, obteniendo una mayor pérdida ponderal que con el tratamiento médico convencional y favoreciendo la mejoría o remisión de las comorbilidades asociadas. Las técnicas de CB más utilizadas en la actualidad son el bypass gástrico laparoscópico en Y de Roux (BGYRL) y la gastrectomía tubular laparoscópica (GTL). Éstas han obtenido resultados similares tanto en cuanto a la pérdida de peso como a la remisión de ciertas comorbilidades como la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 o la hipertensión arterial.

Un rasgo diferencial entre ambas técnicas podría ser el diferente impacto sobre el perfil lipoproteico. Así, estudios previos con seguimiento a corto y medio plazo han objetivado una superioridad del BGYRL frente a la GTL en la reducción del colesterol total y LDL. Existen resultados discordantes en cuanto a la evolución del colesterol HDL y los triglicéridos. Por todo ello, hemos considerado de interés revisar los efectos de la CB a corto y medio plazo en el perfil lipoproteico, así como las tasas de remisión de las diferentes alteraciones lipídicas y los posibles factores relacionados.

Obesity is a chronic metabolic disease with a multifactorial origin. It is defined as excess weight due to the accumulation of body fat. It is classified according to the body mass index (BMI) of each individual, and severe obesity is considered to exist when the BMI is above 40 kg/m2.1

It has become exponentially more prevalent in recent years, and it is now a public health problem of the first order. It is estimated that up to 1.6 billion people in the world are overweight and 400 million are obese, with the resulting increase in cardiovascular morbimortality.2

Two recent cross-sectional studies in Spain have reflected similar rates of obesity. Thus the ENRICA3 study in a population above 18 years old found a prevalence of obesity close to 23%, and the ENPE4 study of a non-institutionalised population aged from 25 to 64 years old found a frequency of obesity of approximately 22%.

Obesity often has associated comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia and the syndrome of apnoea obstructing sleep. All of these factors would justify the increase in cardiovascular risk, leading to higher rates of mortality.5 Likewise, in recent years a clear association has been found between obesity and the risk of certain neoplasms, including those of the colon and rectum, the breast in post-menopausal women, as well as the endometrium, kidneys, oesophagus and pancreas.6

Obesity-associated lipid profile alterationsDyslipidemia caused by obesity is characterised by quantitative and qualitative lipoprotein alterations.7 The lipid profile alterations found in patients with a high BMI are similar to those found in insulin-resistant patients with DM2. The reduced capacity of insulin to inhibit the production of glucose by the liver, as well as favouring the use of glucose by the muscles, leads to a state of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Nor is insulin able to inhibit lipolysis of the triglycerides by the lipase lipoprotein in the adipose tissue, so that the flow of adipocyte-free fatty acids to the liver increases, leading to an increase in visceral fat.8

The increase in fatty acids, chiefly in the liver and muscles, with a reduction in the peripheral absorption of the same, leads to an increase in the hepatic synthesis of very low density lipoproteins (VLDL).9 Finally, the state of hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia also stimulates lipogenesis de novo due to the activation of SREBP-1 protein.

All of these physiopathological changes give rise to the characteristic lipid profile of patients with obesity, consistent with a reduction in high density cholesterol lipoproteins (HDL), hypertriglyceridemia and an increase in the number of small dense low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, known as atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD).10

Cardiovascular risk associated with atherogenic dyslipidemiaLDL cholesterol is not only a cardiovascular risk factor, as it is also considered to be a causal factor of atherosclerosis. This is why it is the main therapeutic target in cardiovascular risk prevention guides. These mainly centre their recommendations on LDL cholesterol targets11 or treatment using statins,12 which are considered to be the first line of treatment for patients with hypercholesterolemia.

Nevertheless, it seems that patients con obesity, even with LDL cholesterol levels at therapeutic target levels, have a residual cardiovascular risk of from 65% to 80%.13 This residual risk can be explained, at least in part, by the characteristic AD of this group of patients. On the other hand, small dense particles of LDL, which are also components of AD, play an important role in the onset and progression of atherosclerosis.14

In spite of the close association between obesity and this atherogenic profile, AD is often under-diagnosed, under-treated and therefore under-controlled. In the lipid units in our area, of a total of 1649 patients, 36.6% had high levels of triglycerides and 36.1% had low levels of HDL cholesterol, while 18% had both alterations. However, only 16% of the patients achieved the therapeutic objectives, and the predictive factors for success were weight and glycemic profile normalisation.15 This would be explained in part by the prioritisation of the therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol in preventing cardiovascular risk while regarding the AD profile as secondary.

Bariatric surgeryBariatric surgery (BS) is considered to be the most effective treatment for patients with morbid obesity, as it brings about a weight loss that may surpass 30%, and which is maintained over the long term.16 This percentage is far higher than is the case for the results of medical treatment that emphasises lifestyle changes, achieving a weight loss of from 5% to 10%, although normally there is a gradual gain in weight over one to two years. In the LOOK AHEAD17 study, which analysed the effect of a therapeutic strategy centring on lifestyle modification, only 34.5% of the intervention group lost 10% of weight in the first year, and only 42.4% of those who had a satisfactory initial response kept this weight loss 4 years later. On the other hand, pharmacological treatment for obesity achieved weight losses of from 4% to 11%; these figures are lower than those for BS.

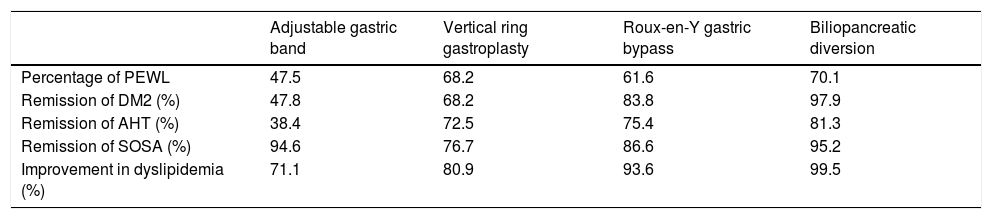

It has to be said that the role of BS goes beyond the said weight loss. It has also been shown to bring about an improvement or remission in different comorbidities after surgery. A meta-analysis by Buchwald et al.18 in 2004 included data from 136 studies with a total of 22,094 patients. 72.6% of the patients were women, with an average age of 39 years old (16–64 years old) and an average BMI of 46.9 kg/m2 (32.3–68.8 kg/m2). A significant weight loss was observed in the patients with obesity who were subjected to BS, with improvement or resolution of 86% and 70% in DM2 and dyslipidemia, respectively (Table 1).

Main findings of the meta-analysis by Buchwald et al.

| Adjustable gastric band | Vertical ring gastroplasty | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | Biliopancreatic diversion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of PEWL | 47.5 | 68.2 | 61.6 | 70.1 |

| Remission of DM2 (%) | 47.8 | 68.2 | 83.8 | 97.9 |

| Remission of AHT (%) | 38.4 | 72.5 | 75.4 | 81.3 |

| Remission of SOSA (%) | 94.6 | 76.7 | 86.6 | 95.2 |

| Improvement in dyslipidemia (%) | 71.1 | 80.9 | 93.6 | 99.5 |

DM2: type II diabetes mellitus; AHT: arterial hypertension; PEWL: percentage of excess weight loss; SOSA: syndrome of obstructive sleep apnoea.

Source: Buchwald et al.18

All of these beneficial effects of BS led to a reduction in mortality of almost 30% at 10 years,16 possibly because of a reduction in cardiovascular risk.

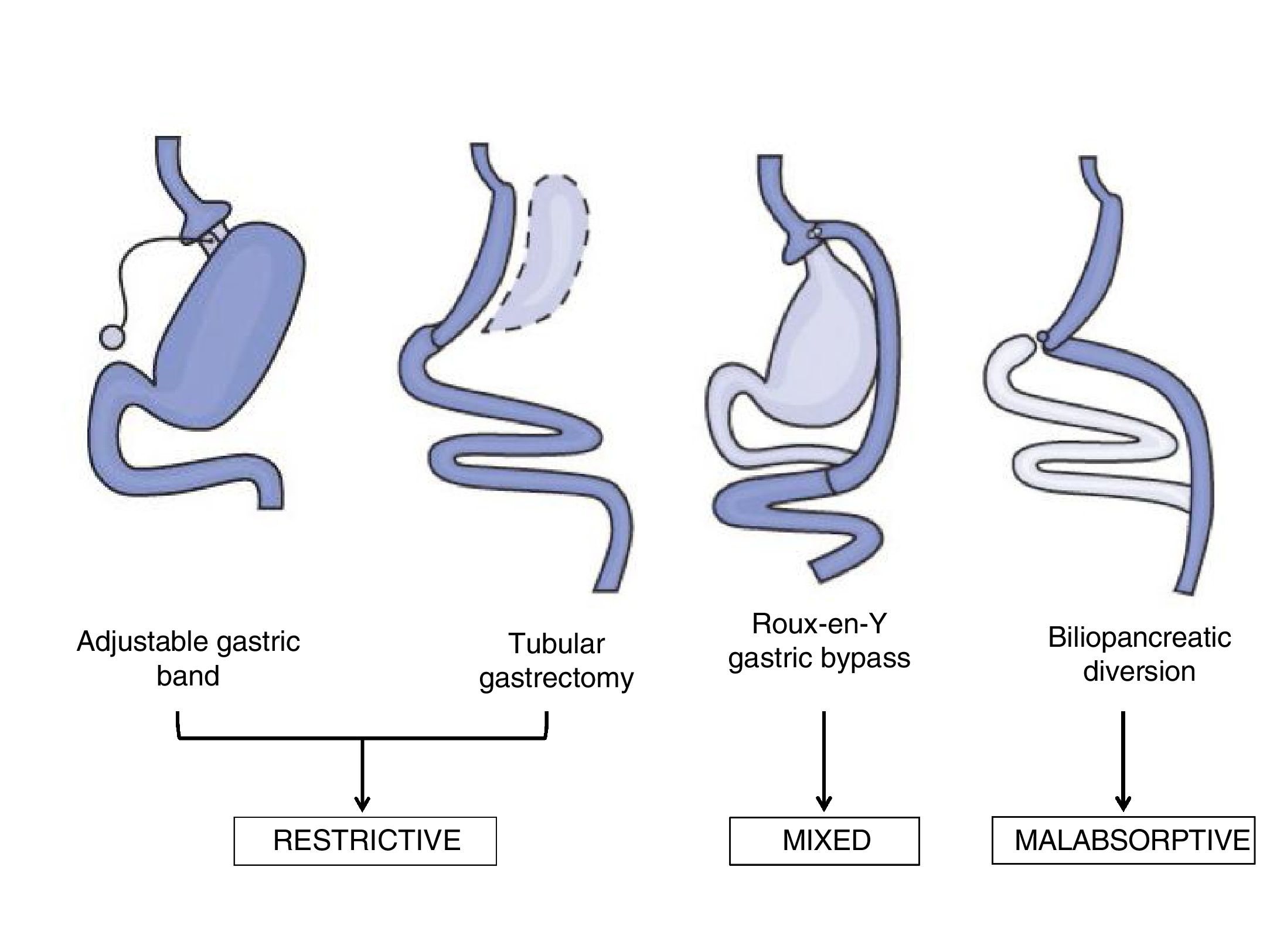

Bariatric surgery techniquesThe surgical techniques used in the field of BS may be classified as malabsorptive, restrictive and mixed (Fig. 1). Malabsorptive techniques such as the biliopancreatic diversion reduce intestinal length and therefore reduce nutrient absorption. Although these techniques give greater weight loss over the long term, they are now used less often due to the risk of nutritional deficits, and because of the higher rate of morbimortality associated with the procedure. On the other hand, use of purely restrictive techniques such as an adjustable gastric band or ringed vertical gastroplasty is limited because of their results in terms of weight loss or the remission of comorbidities.19

The most widely used techniques now are laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic tubular gastrectomy (LTG), due to their short-term results in terms of weight loss and resolution of the comorbidities associated with obesity.18 LRYGB is a mixed technique that combines partial exclusion of the stomach by means of gastroplasty with a bypass of the duodenum with the proximal jejunum, with the resulting effect of malabsorption. For many years this has been considered to be the technique of choice due to its good results, with a better balance between efficacy and adverse effects.18 It also seems that its efficacy is determined by other mechanisms which go beyond the weight loss observed after this surgical procedure.20

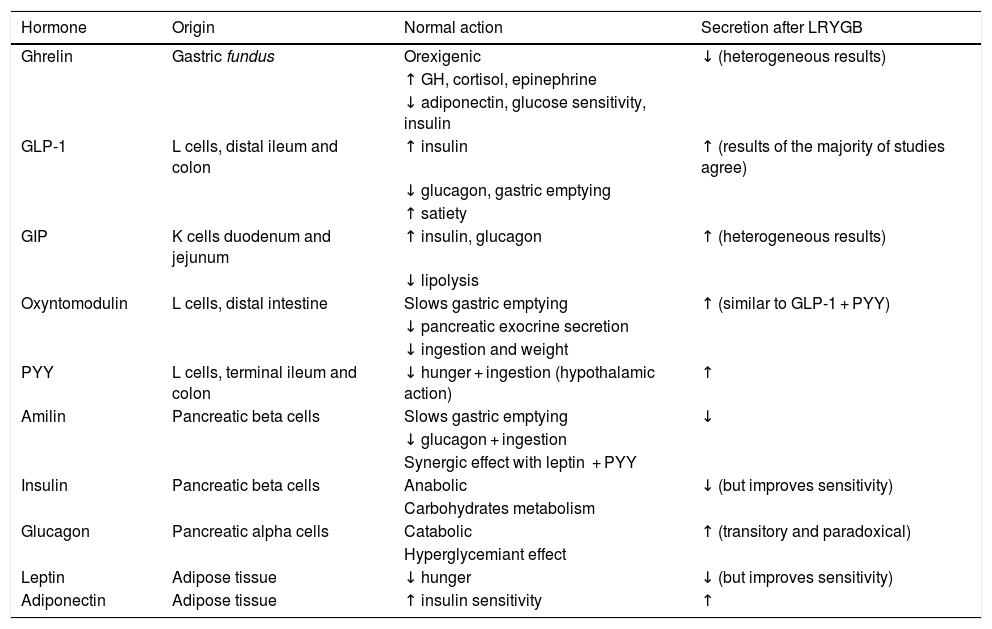

Different alterations have been observed in the gastrointestinal hormones associated with satiety and ingestion after LRYGB. On the one hand, there is an increase in hormones with an incretin effect, such as the peptide similar to type 1 glucagon (GLP-1) and the YY (PYY) peptide over the short term after surgery, and their levels remain high over the long term.21 Among other functions, the incretin hormones favour insulin secretion and delay gastric emptying, contributing positively to weight loss and improved carbon hydrate metabolism. Other hormones are modified after del LRYGB, as described in detail in Table 2.

Summary of the main actions of the hormones which are altered after LRYGB.

| Hormone | Origin | Normal action | Secretion after LRYGB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghrelin | Gastric fundus | Orexigenic | ↓ (heterogeneous results) |

| ↑ GH, cortisol, epinephrine | |||

| ↓ adiponectin, glucose sensitivity, insulin | |||

| GLP-1 | L cells, distal ileum and colon | ↑ insulin | ↑ (results of the majority of studies agree) |

| ↓ glucagon, gastric emptying | |||

| ↑ satiety | |||

| GIP | K cells duodenum and jejunum | ↑ insulin, glucagon | ↑ (heterogeneous results) |

| ↓ lipolysis | |||

| Oxyntomodulin | L cells, distal intestine | Slows gastric emptying | ↑ (similar to GLP-1 + PYY) |

| ↓ pancreatic exocrine secretion | |||

| ↓ ingestion and weight | |||

| PYY | L cells, terminal ileum and colon | ↓ hunger + ingestion (hypothalamic action) | ↑ |

| Amilin | Pancreatic beta cells | Slows gastric emptying | ↓ |

| ↓ glucagon + ingestion | |||

| Synergic effect with leptin + PYY | |||

| Insulin | Pancreatic beta cells | Anabolic | ↓ (but improves sensitivity) |

| Carbohydrates metabolism | |||

| Glucagon | Pancreatic alpha cells | Catabolic | ↑ (transitory and paradoxical) |

| Hyperglycemiant effect | |||

| Leptin | Adipose tissue | ↓ hunger | ↓ (but improves sensitivity) |

| Adiponectin | Adipose tissue | ↑ insulin sensitivity | ↑ |

LRYGB: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; GIP: gastric inhibitor peptide; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide type 1; PYY: YY peptide.

Adapted from Ramos Leví AM, Rubio Herrera MA. Cirugía metabólica. In: Bellido D, et al. Sobrepeso y obesidad. Sociedad Española para el estudio de la obesidad. Madrid; 2015. pp. 603–620.

The concentration of biliary acids also increases after LRYGB,22 and on the other hand, alterations have been described, mainly in animal models, in the intestinal microbiota after this procedure.23

LTG is a technique that was performed for the first time in 1988 as a variant of the biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch.24 Subsequently, at the beginning of the 21st century its use was based on first step surgery before using a malabsorptive technique in patients with extreme obesity (BMI > 50 kg/m2).25 A second operation was unnecessary for the majority of patients, given the good weight loss results. LTG therefore became an operation that was definitive in many cases.26 LTG consists of a subtotal vertical gastrectomy with preservation of the pylorus, including a longitudinal resection of the fundus, the gastric body and antrum. The resection compromises approximately 80% of the stomach, with a gastric remnant of >100 ml. It is considered to be the simplest surgical technique in comparison with others, such as LRYGB, as it requires less anastomosis and has a lower rate of complications.

Although LTG is a restrictive technique, it has obtained better results than other restrictive techniques, similar to LRYGB in terms of weight loss and the short-term remission of certain comorbidities.27 This may be attributed to different mechanisms that go beyond the restrictive component. Some of the factors described, in a similar way to LRYGB, are associated with modifications to intestinal motility, hormonal mechanisms and alterations in the biliary acids or intestinal microbiota.28

LTG is now considered to be far more than a restrictive technique, and it overtook LRYGB in 2014 to become the most widely used technique in the world.29 In Spain, LTG has progressed from representing 0.8% of all cases of BS to become the second most widely used, at 39.6%, and it is only surpassed by LRYGB.30 Nevertheless, although the medium to long-term results for LRYGB are well-known, this is not the case for LTG, as it is a relatively new technique, so that it has yet to be confirmed whether these techniques are equivalent by longer clinical follow-up studies.

The effects of bariatric surgery on the evolution of the lipid profileBS is universally acknowledged to be better than conservative medical treatment in terms of weight loss and the remission of several comorbidities, with the resulting reduction in cardiovascular risk.

In the case of dyslipidemia, the meta-analysis by Buchwald et al.18 found an improvement or resolution of 70%, with similar results to those of previous studies that evaluated the overall remission of dyslipidemia.31,32 This gives rise to certain limitations, as firstly there is no unanimous agreement on the definition of the remission of dyslipidemia, so that the results of different studies are not always comparable. Secondly, the fact that dyslipidemia is evaluated as a whole means that the evolution of different lipid fractions is not taken into account.

On the other hand, and as was pointed out above, the characteristic lipid alteration in patients with obesity is composed of reduced levels of HDL cholesterol and hypertriglyceridemia. The evaluation of this atherogenic profile after BS is indispensible, as it may explain the reduction in residual cardiovascular risk shown by these patients.33 Thus previous studies have observed a fall of from 30% to 63% and an increase of from 12% to 39% in triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, respectively, after BS.34,35 Similarly, a study by our group evaluated the remission of AD one year after LRYGB and LTG.36 AD was present in 81 of 356 patients (22.8%), and in 74.1% remission occurred by 3 months and 90.1% at 6 months, reaching 96.3% at 12 months after the surgical procedure. Likewise, HDL cholesterol rose 6 months after BS in both groups (with and without AD), with a significantly greater increase in the atherogenic profile group (47.6 ± 31.6 versus 24.1 ± 23.2%, respectively; P < .001). There was also an evident improvement in triglycerides in the first three months after surgery in both groups, with a significantly greater reduction in the group with AD during the entire follow-up period (49.3 ± 21.3 versus 21.2 ± 53.0%, respectively; P < .001).

Differences between LRYGB and LTG in terms of lipid profile evolutionRegarding the different techniques of BS, in the majority of studies LRYGB and LTG obtained comparable results in terms of weight loss and the remission of several associated diseases over the short to medium term.37–40

It seems that the difference between both surgical procedures may lie in their effect on the lipid profile. Thus, in studies with a short follow-up period LRYGB has been said to be superior to LTG in how it improves concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol.41,42 However, the short-term results for triglycerides and HDL are contradictory.43,44 One study by our group45 with a one-year follow-up included 51 patients treated by LRYGB and 51 treated by LTG. The results concluded that the mixed technique improved all of the lipid fractions, while the restrictive technique, although it had no effect on LDL cholesterol levels, had the same or more effect as the malabsorptive techniques in increasing HDL cholesterol. On the contrary, the study by Vix et al.,46 which included 45 patients in the LRYGB group and 55 in the LTG group, with a one-year follow-up, found that the first group performed better in reducing total and LDL cholesterol and raising HDL cholesterol, with no differences between the techniques respecting triglyceridemia. Given the heterogeneous results of comparing lipid profile evolution after LRYGB or LTG over the short term, our group decided to compare the different studies published to date in a meta-analysis.47 A total of 17 papers were included (4 randomised clinical trials, 6 cohort studies and 7 control cases). Hypercholesterolemia remission was greater after LRYGB than it was after LTG (relative risk: 1.43; CI 95%: 1.27–1.61), and no differences were found between the two surgical techniques in hypertriglyceridemia evolution (relative risk: 1.11; CI 95%: 1.00–1.23) or low HDL cholesterol (relative risk: 0.96; CI 95%: 0.02–57.28). The change in the concentration of different lipid fractions was also evaluated. LRYGB was superior to LTG in terms of the reduction in total cholesterol (average difference: 19.77 mg/dl; CI 95%: 11.84–27.69). A greater fall was also detected in LDL cholesterol after LRYGB in comparison with LTG (average difference: 19.29 mg/dl; CI 95%: 11.93–26.64). On the other hand both surgical techniques were similar in terms of their results for triglycerides (average difference: −1.19 mg/dl; CI 95%: −10.99 to 8.60), as well as the rise in HDL cholesterol concentration (average difference: .47 mg/dl, CI 95%: −1.43 to 2.37).

Furthermore, very few studies compare LRYGB to LTG over 5 years in terms of lipid profile evolution.48,49 The majority evaluated the overall remission of dyslipidemia, as did Zhang et al.50 They found a remission of 92.3% and 84.6% at 5 years after LRYGB and LTG, respectively, although the differences were not significant. Other studies evaluated changes in the concentrations of different lipid fractions after BS. Thus the recently published randomised clinical trial SLEEVEPASS51 (119 patients treated by LRYGB and 121 by LTG) found lower levels of LDL cholesterol LDL 5 years after LRYGB in comparison with LTG (96.5 mg/dl versus 104.3 mg/dl; P = .02). Likewise, the SM-BOSS52 study (with 110 patients operated using LRYGB and 107 using LTG), and following the same line, also found a greater reduction in LDL cholesterol after the mixed technique in comparison with the restrictive technique (101.1 mg/dl versus 116.1 mg/dl; P = .008). However, neither study found differences between the techniques respecting other lipid fractions.

Finally, a recent study by our group53 compared the results 5 years after LRYGB and LTG. This evaluated the change in concentration as well as the remission of hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol. 151 of the 259 patients (58.3%) completed 5 years of follow-up, of whom 103 (68.2%) had received LRYGB and 48 (31.8%) LTG. Hypercholesterolemia remission (26/58 [44.8%] versus 6/26 [23.1%]; P = .047) as well as high LDL cholesterol (30/49 [61.2%] versus 6/23 [26.1%]; P = .005) at 5 years were all greater after LRYGB than they were after LTG. Nevertheless, the number of patients who achieved normal levels of HDL cholesterol at 5 years after surgery was similar in both techniques (39/47 [83.0%] and 18/23 [78.3%] after LRYGB and LTG, respectively; P = .633). Hypertriglyceridemia remission at 5 years was greater after LRYGB than it was after LTG (23/25 [92.0%] versus 10/15 [66.7%]; P = .041). However, LTG showed a higher rate of relapse during follow-up.

Factors associated with the remission of lipid profile alterationsFinally, little is known about the factors associated with changes in the lipid profile after BS. Regarding this, and with a follow-up of one year, a study by our group45 found that at a younger age, concentrations of total cholesterol and LRYGB were associated with improvement in total cholesterol. The same factors (except age) were found to be associated with a reduction in LDL cholesterol levels. Regarding HDL cholesterol, a rise in its levels after BS was associated with an older age, initial levels of HDL cholesterol and the LTG procedure. A reduction in triglyceride levels was associated with basal triglyceride levels and HbA1c.

Another study by our group that was cited above53 evaluated factors associated with the remission of different lipid profile alterations at 5 years. Thus the factors associated with the remission of hypercholesterolemia were male sex, LRYGB and the absence of initial treatment with statins. The absence of initial treatment with fibrates and the percentage of weight loss after 60 months were associated with the remission of hypertriglyceridemia, and this was the only factor associated with the remission of low HDL cholesterol.

ConclusionsA range of associated comorbidities are present in patients with obesity. They include AD, which causes the high residual cardiovascular risk in these patients.

On the other hand, BS has been shown to be the most effective treatment for obesity, and LRYGB and LTG are now the most widely used techniques. Both procedures have given similar results in terms of weight loss and the remission of several comorbidities. Nevertheless, for the lipid profile it seems that LRYGB is superior to LTG regarding the evolution of plasma concentrations of total and LDL cholesterol. However, the results for HDL cholesterol and triglycerides are contradictory.

Further randomised studies with a longer clinical follow-up are therefore required, to confirm the preliminary results obtained and thereby underline any possible differences between both surgical procedures regarding the evolution of the lipid profile.

FinancingThis study received no specific support from agencies in the public sector, the commercial sector or not-for-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Climent E, Benaiges D, Goday A, Villatoro M, Julià H, Ramón JM, et al. Obesidad mórbida y dislipemia: impacto de la cirugía bariátrica. An Pediatr (Barc). 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2019.11.001