In this paper, a case study is presented. The client had been in therapy before, and had abandoned all previous treatments before any significant improvement had taken place. In the treatment reported here, she committed to the therapy and made progress. Possible reasons for this change in adherence are discussed.

En este estudio se presenta un caso. La cliente había estado ya en terapia, abandonando todos los tratamientos previos antes de que su problema hubiera mejorado significativamente. En el tratamiento reseñado aquí finalmente se comprometió con la terapia y mejoró. Se discuten posibles explicaciones para este cambio en la adhesión terapéutica.

In this paper, a case of non-compliance and therapeutic abandon is presented. After three failed treatments conducted by different therapists from the same clinic, who worked under the same theoretical and clinical approach, finally the client commits to a treatment and follows it to its conclusion. We will analyze here some possible factors that may have contributed to the client's improvement but, mainly, to her commitment with a therapy that was fundamentally identical to those she had previously abandoned.

The question of where to find the factors that might account for the change in the client's behavior towards her commitment with the clinical process is undoubtedly mediated by the theoretical model from which we look at the clinical setting. In our case, as behavioral therapists and behavior analysts, we necessarily will look for these factors in the client's environmental contingencies and the different interaction styles of the therapists. For a better understanding of this approach based in the analysis of the therapist's and client's verbal behavior in session, we recommend reading Froján, Calero, Montaño, and Ruiz (2011).

One of the main concerns of any clinician is the client's adherence to the treatment, both as compliance with specific instructions as, on a broader level, commitment to the treatment and the changes that are needed in order for it to progress in the adequate way towards the clinical targets that were set. Talking about this commitment of the client to change, which is a prerequisite for the achievement of the therapy's targets, forces us to refer to some topics that are related to each other and to clinical change itself: from the therapeutic relationship as a climate that will, if properly created, stimulate the client's compliance and improvement to motivation in therapy and the most adequate way to give instructions.

Regarding the therapeutic relationship, consistently found to be one of the main factors that account for clinical success (Andrews, 2000; Castonguay, Constantino, & Grosse, 2006; Lambert, 1992), we consider it very fruitful and clinically useful for it to be thought of as the product of a clinical interaction that is shaped and directed by the therapist through his/her behavior during the clinical session (Froján et al., 2011), and which plays, or might play, a dispositional role in improving the odds of the client following the therapist's instructions. This is to say that the way in which the therapist interacts with his/her client has an effect in the way in which they commit to the clinical process and follows instructions or advances towards the clinical targets (Callaghan, Summers, & Weidman, 2003; Karpiak & Benjamin, 2004; Truax, 1966).

The content of these therapist's utterances that will more frequently help making the client commit to change is a topic generally researched as part of the field of motivation in therapy. When asked about what motivating in therapy is, experts will give a wide variety of answers, such as verbally anticipating positive consequences of change (Newman, 1994; Ruiz, 1994, 1998), remarking about those that were already obtained in the past (Cormier & Cormier, 1994), alluding to other clients’ improvement (Ruiz, 1998), psychoeducation (Froján & Santacreu, 1999; Gavino, 2002; Newman, 1994), verbally anticipating problems that may appear should the client remain in his/her current state (Blume, Schmaling, & Marlatt, 2006; Hall, Weinman, & Marteau, 2004; Kanfer, 1992; Meichenbaum & Turk, 1991), explaining their problem to them in terms of causal relations and how to modify them (Meichenbaum & Turk, 1991; Ruiz, 1998), or underlining the relation between the expected changes and the client's values (Meichenbaum & Turk, 1991; Ruiz, 1998). What all these possible ways to motivate have in common is the fact that they are ways to verbally specify a contingency of the “if you do X, Y will happen” kind, X being a more or less complex, complete detailing of the client's homework issued by the therapist. It seems, then, that according to experts, the best way to help the client commit to change is through the highlighting of the consequences on his/her life in general and his/her problem in particular that are to be expected from his/her actions.

As for adherence, we agree with Martin Alfonso (2004) in their notion that the therapist's in-session behavior, which is fundamentally verbal, has or may have an effect on the odds of the client following instructions or not. We also believe it is fundamental for the client's adherence and compliance to be considered as a behavioral factor encompassing the client's behavior but also his/her interaction with the therapist. This interaction between the therapist's and the client's behavior in relation to compliance might be mediated by the way in which the clinician issues the instructions (Marchena-Giráldez, Calero-Elvira, & Galván-Domínguez, 2013).

Occasionally, researchers delving into this phenomenon of the same client being involved in several clinical failures followed by a success invoke as an explanation the idea that the client was not in the right “motivational stage” to commit to change, a description in line with the considerably popular Transtheoretical Model of Change (TMC) proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska, diClemente, & Norcross, 1992), which assumes that the process of clinical change of a client will go through given phases or stages. Following this model, the fact that the client did not commit to previous treatments would be explained, according to these authors, by her not being in the right motivational stage. The fact that she eventually committed to another treatment would be explained by her being in a stage of commitment to change. However, and in line with what Froján, Alpañés, Calero, and Vargas (2010) point out, the TMC has considerable problems both in its theory and its practice: the stages’ definition and order are arbitrary, with no noticeable difference in clinical outcome that can be attributed to adapting interventions or treatments to the stage through which the client is supposedly going through in a given moment. What is more: should this theory be used to explain the clinical changes or lack thereof in the case we here present, we would be incurring in a circular reasoning that we deem inappropriate. Hence, we will focus on the analysis of clinical interaction in the different treatments as a source of possible explanations for the difference in outcome between said treatments.

Description of Previous TreatmentsThe client (henceforth E.) started attending therapy in the summer of 2008, when she was 27, to try and solve her anxiety problems, which were mostly related to her job as a speech therapist in a school. Her first contact with psychological therapy, however, happened one year before, in the form of a single session in which she was given some guidelines regarding anxiety and how to control it.

Two years later, in the winter of 2010, she came back to the same clinic, with the same problem. She was now treated by a different therapist. In that moment she felt unable to go to work or leave her home, and had trouble interacting with other people, along with doubts concerning her (at the time) impending wedding. She was on a 4-day sick leave authorized by her doctor, who had also prescribed Transilium (benzodiacepine) and Rexer (anti-depressant). The client feared she was having another depressive episode, since she had had two of these before (in 2001 and 2007), also while she was medicated.

This second psychological treatment (henceforth Treatment 2) consisted of 3 assessment sessions (using interviews with the client and her relatives as an assessment tools, along with homework that consisted mainly in the client having to take notes about her thoughts in difficult situations and pleasurable situations) and 4 treatment sessions, one of which consisted mainly of the explanation of the functional analysis (that will be detailed later, since it is broadly the same in all interventions underwent by the client). In this intervention phase, several clinical targets were proposed. These will also be detailed later, because they were mostly the same throughout all of the client's treatments. This treatment was interrupted by the client citing her wedding as a reason, even though it had not yet been considered complete.

After Treatment 2, the client was medicated with anti-depressants for 10 months, experimenting a slight improvement of her symptoms due to her adaptation to her new marital life and also to convenient changes in her job (a new Head of Studies had been appointed, and she was in charge of what she perceived to be an “easier group” of children). She kept her good mood until she had to take care of a group of children with learning difficulties (which meant a slower progression and being exposed to more responsibilities and critics). Through several months, the anxiety responses had been increasing, and her mood getting worse even while being treated with Transilium. She decided to start a new psychological therapy in the summer of 2012 (henceforth Treatment 3) with a different therapist. She complained of a low mood, high anxiety, and a general dissatisfaction with her life. She had lost a lot of weight, she did not rest enough at night and she had a very negative speech about her job, her skills, her marital relationship and her vital situation. She was also very worried about this recurrence of her problems. In this occasion, she was trying not to take a sick leave, and also to keep active and discuss with herself her negative thoughts in an effort to refute them.

Treatment 3 consisted of 6 sessions: 3 assessment sessions and 3 treatment sessions, one of which was mostly dedicated to the explanation of the functional analysis of her problem. The last two sessions took place after the treatment was interrupted for a month.

Information was gathered for the assessment phase using various strategies: interviews with the client and her relatives and different data-collection sheets completed by the client herself. In this assessment phase, there was some psychoeducation too, a verbal reinforcement of positive coping behavior, and guidelines to stymie the progressively more severe situation.

The treatment phase was directed towards the achievement of the clinical targets (detailed later in this text) and, much like Treatment 2, consisted of the training of specific techniques and tasks that were instrumental in reaching the targets.

In this occasion, the client experimented a deterioration of her situation (both her mood and anxiety levels) after the summer holidays, which was associated to the start of the academic year, when she found out she was to take care again of the same group of children with learning difficulties. By session 6, she has asked for sick leave and manifested her intention of abandoning psychological therapy and choosing pharmacotherapy, citing “lack of improvement” as a reason for this. The therapist urges the client to give the therapy more time in order for changes to appear, but the client cancels session 7 via phone, saying she prefers to give more time for her medication to work.

Fourth (Current) TreatmentBetween the previous treatment, abandoned by E., and this one, two years had passed. In this period, E. has gone through some very stressful situations: some of her students’ parents formally complained to the school board saying she was mistreating the children by yelling at them. Despite all the support she had from an ample majority of her students’ parents, who even wrote a letter in her defense to the board, E. was subject to an inspection by the competent authorities. For a whole year, all her work was overseen by an inspector who even was present while she was working in the classroom. The relationship between E. and this inspector was quite fraught, since, according to E., “it seemed like [she] did everything wrong”, and the inspector remarked on this “in a very rude manner”. She could not understand why everything she did was wrong, when “everyone else” did it the exact same way without being subject to the same scrutiny to which she was subject. Daily, E. drove the approximately 40 kilometers from her home to her workplace in a very anxious mood that only got worse once she reached the school in which she worked. She cites tachycardia, sweating, and uncontrolled crying as symptoms of this anxiety. After her working day ended, she drove back home, where she worked all through the evening to “comply” with the guidelines set by the inspector. Often she kept working until it was time to dinner, in a constant state of anxiety that made it difficult for her to concentrate, which meant she wasted a lot of time. After having dinner she went to bed, although it took up to two hours for her to actually fall asleep.

This situation continued for a year. In her summer holidays, she traveled abroad with her husband, L., and she describes this trip as “very nice”. She remembers she was calm and relaxed, with no sleeping problems and in a better mood. All these improvements came to an end when her holidays ended and she had to go back to her work. All anxiety symptoms reappeared and worsened, and generalized from her workplace to driving in her car, or even riding any car – even if she wasn’t driving. Seeing that her work was starting to be hugely affected by all this, she asked for a sick leave and started on medication prescribed by a psychiatrist and her family doctor. Both of them told E. that her problem was chronic and she would be in that state all her life, even going so far as to tell her that she wouldn’t be able to ever have children because she was going to be medicated for life. Rebelling against this, and considering that the guidelines she had actually followed had had a positive impact in her problem (especially keeping active and try to go out of home even if she didn’t want to), E. again resorted to psychological therapy in the same clinic she had attended for her previous treatments.

This fourth treatment (henceforth Treatment 4) has lasted for 24 sessions, 4 of them being of assessment, 16 of treatment (including one that consisted mostly of an explanation of the functional analysis of her problem and the description of the clinical targets and the techniques that were to be used), and 4 follow-up sessions. She currently is in this follow-up phase, with sessions every two weeks.

Assessment PhaseThe assessment was carried out through interviews with the client and her husband and the use of data sheets that were to be filled in by the client (one for complicated situations and a questionnaire of reinforcing stimuli, in order to find things or activities that she found nice, entertaining, or fun).

During this phase, E. provides quite a lot of information about the origin and permanence of her problem, while clearly showing her interactive style, which is heavily focused on complaining and getting help from her social surroundings (especially from her husband, L.), that systematically reinforces with attention any expression of distress and/or any sign of negative emotions such as crying or issuing utterances like “I’m going to be like this forever”. She cries frequently, and her eyes fill with tears easily. Her difficulty to commit to tasks set by the therapist is also made clear, even with those that are comparatively simple like information sheets. In virtually every session, she asks for the therapist to e-mail her the tasks she has to perform as well as key points of the therapist's explanations. Besides this, she tries almost every week to get in touch with the therapist, be it via phone or e-mail, outside of the appointed dates for her sessions. In these contacts, she alludes to her difficulty to remember the things she was told to do or her fear of her sick leave being revoked, which would mean she would have to go back to work immediately. In these moments, the therapist reminds her of their appointment while trying to relativize her fears.

Just as was done in previous treatments, during this phase the therapist makes a point of correcting the explanations that E. gives herself about her situation, as well as giving some quick guidelines and strategies that could improve her mood before the treatment phase begins (for example, telling her to go shopping after the session, something she enjoyed).

Functional AnalysisThere are a few dispositional variables that, while not being the direct cause of the problem, have facilitated its appearance, maintenance and recurrence. These are:

- •

Overprotective environment. Ever since she was a child, E. has resorted to her family when faced with problems or decisions, which has made her prone to asking for help to do everything and to going to them for calm, never truly learning to cope with difficulties by herself. She's married to L., with whom she's been for over ten years, and he fills the same role her family did. She goes to him for everything, and feels very dependent on him. Despite loving him dearly, the doubts about her marriage and her relationship, and whether she is a burden to L., are recurrent when she feels sad or anxious.

- •

Confluence of several sources of stress in her environment. The start of her problematic episodes has always been precipitated by the appearance of simultaneous factors with which E. has not been able to adequately cope: the imminence of her wedding and her (unfounded) doubts about it, starting to live with L. far from her overprotective family (with the new responsibilities that come with it), changes in her workplace and side effects of her anti-depressant medication. Regarding these last two factors:

- •

Her job has been a source of stress due to several reasons:

- -

In the first place, her job itself: she used to work as a speech therapist in a school (until she applied for a job as an elementary school teacher, which she got), and when things were not wholly favorable – be it because of her bosses, the tasks she had to perform or the group of children with whom she had to work – she felt insecure and overwhelmed, developing job-related anxiety and low mood. When circumstances of her job have been more favorable, E. has felt better in all areas of her life.

- -

Likewise, due to the changes of school (she has worked at three different schools in the last 5 years) and her difficulty interacting with her colleagues, she felt like she was out of place on a regular basis.

- -

Finally, she has serious insecurities about her proficiency in her job. She doubts her own professionalism, and is very worried about what others might think of her and her work. However, she was most often well considered by her coworkers.

- -

- •

Although her medication supported her mood increase, it has become a source of stress, as will be explained later, both between different episodes of the problem (by making E. gain weight) and in them (by affecting her memory, reflexes, and clarity, and the concern that others might notice her state).

- •

- •

The recurrence of these “episodes” of her problem has facilitated the establishment of erroneous ideas about depression as a disease, her predisposition to it, and her helplessness when it came to prevent it.

- •

Concerning her basic abilities:

- •

Cognitive style that tends to focus on and exaggerate all negative and/or problematic things. She reads into things and reaches conclusions without evidence to support them, doubts everything and spends a lot of time thinking about what other might think and pondering her situation over and over. This is also made patent in the way she describes herself (she is very negative when describing herself and her abilities and skills). This has some consequences: 1) it favors a low mood and makes every small problem in her life prone to ending up becoming a big problem; 2) it affects her interactions with other people; 3) it favors the avoidance of every situation in which she feels she does not have control; and 4) she has a hard time enjoying things, since she's too busy focusing on the negative aspects of every situation.

- •

Deficit of adequate coping skills needed to see complicated situations and distress moments through. Her most used strategies have been: staying at home, not coming out of bed, avoiding supposedly problematic contexts, resorting to psychiatrists and medication and leaning on her family for everything. This avoidance and search for support in others has prevented certain erroneous ideas from being put to the test and discarded, which in turn has meant that she hasn’t learned her own coping strategies when faced with new or difficult situations, or those that require initiative and resolution, maintaining her dependence from her environment and her lack of self-confidence. E. just becomes paralyzed and crumbles emotionally very easily when these situations happen, and thus the problem simply reappears when she's faced with any difficulty. Among the strategies she has not fully developed are social skills and assertiveness, both to begin and end conversations and to receive criticism without feeling hurt or questioning her value.

- •

- •

Very dependent on immediate reinforcement. She finds it hard to persist trying to do things or tasks that lack short-term results, or those in which she feels she is not proficient. She has not developed almost any tolerance to frustration. This has an influence in various parts of her life, such as her job (when she has had to work with complicated groups), or her daily life, where she has trouble finishing her daily chores – which is only made worse by the fact that E. works in a very chaotic way, making it difficult for her to actually finish what she started.

- •

Low rate of reinforcing stimulation. Personal leisure time, as well as quality time with her husband and friends, is practically non-existent. She has never had any hobbies, and there is a great difficulty in identifying pleasurable activities or moments. Due to her lack of social skills, she had plenty of aversive stimulation in her life associated with social interaction.

- •

Physical vulnerability to stress. When faced with problems, E. has experienced an increase in basal psychophysiological activation, which manifests in tachycardia, diarrhea, decreased immune system, and herpes. She also loses weight and feels physical weakness. This favors her emotional instability. During the assessment phases of her various treatments, he has shown an appearance of being tired and downhearted.

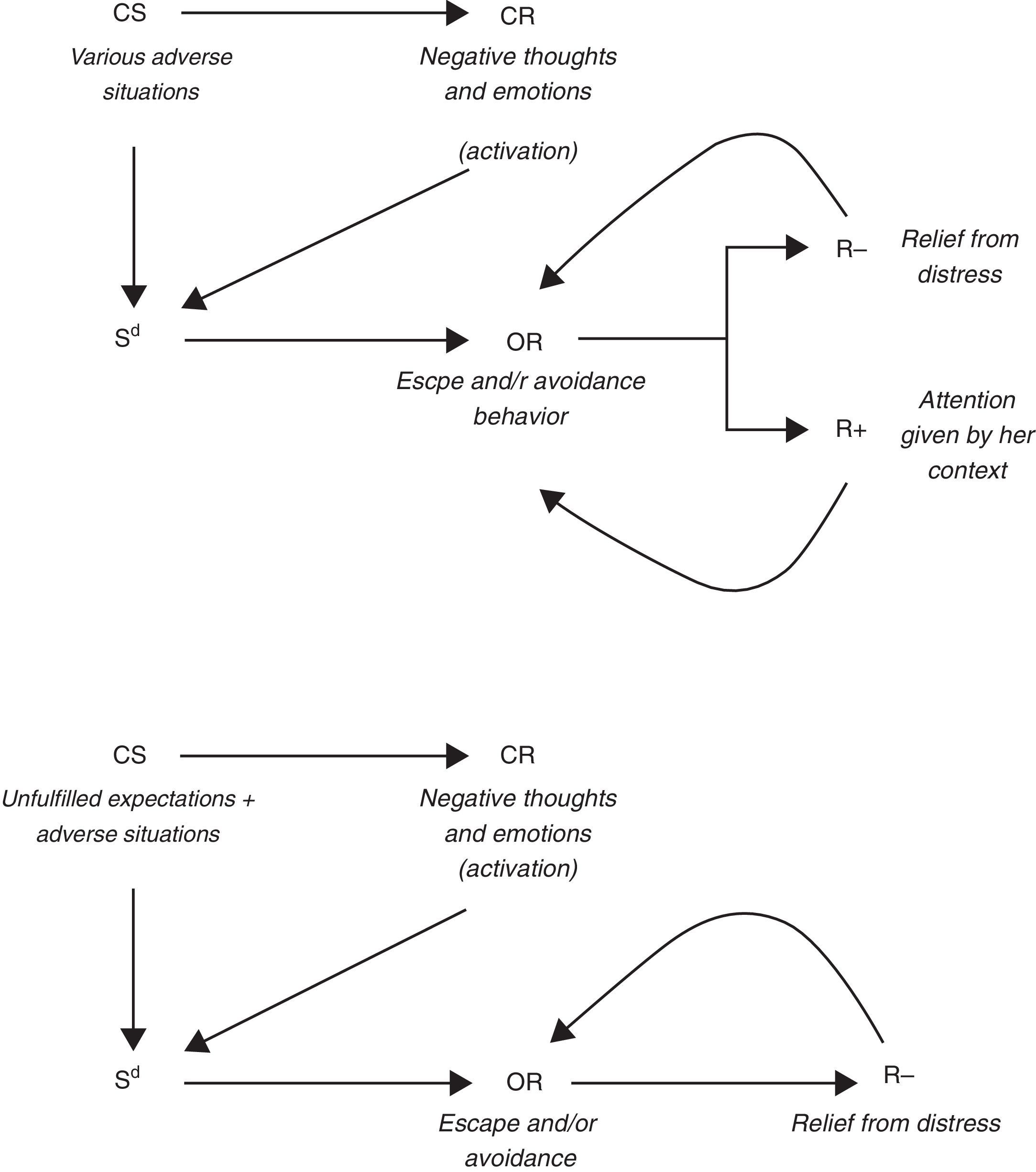

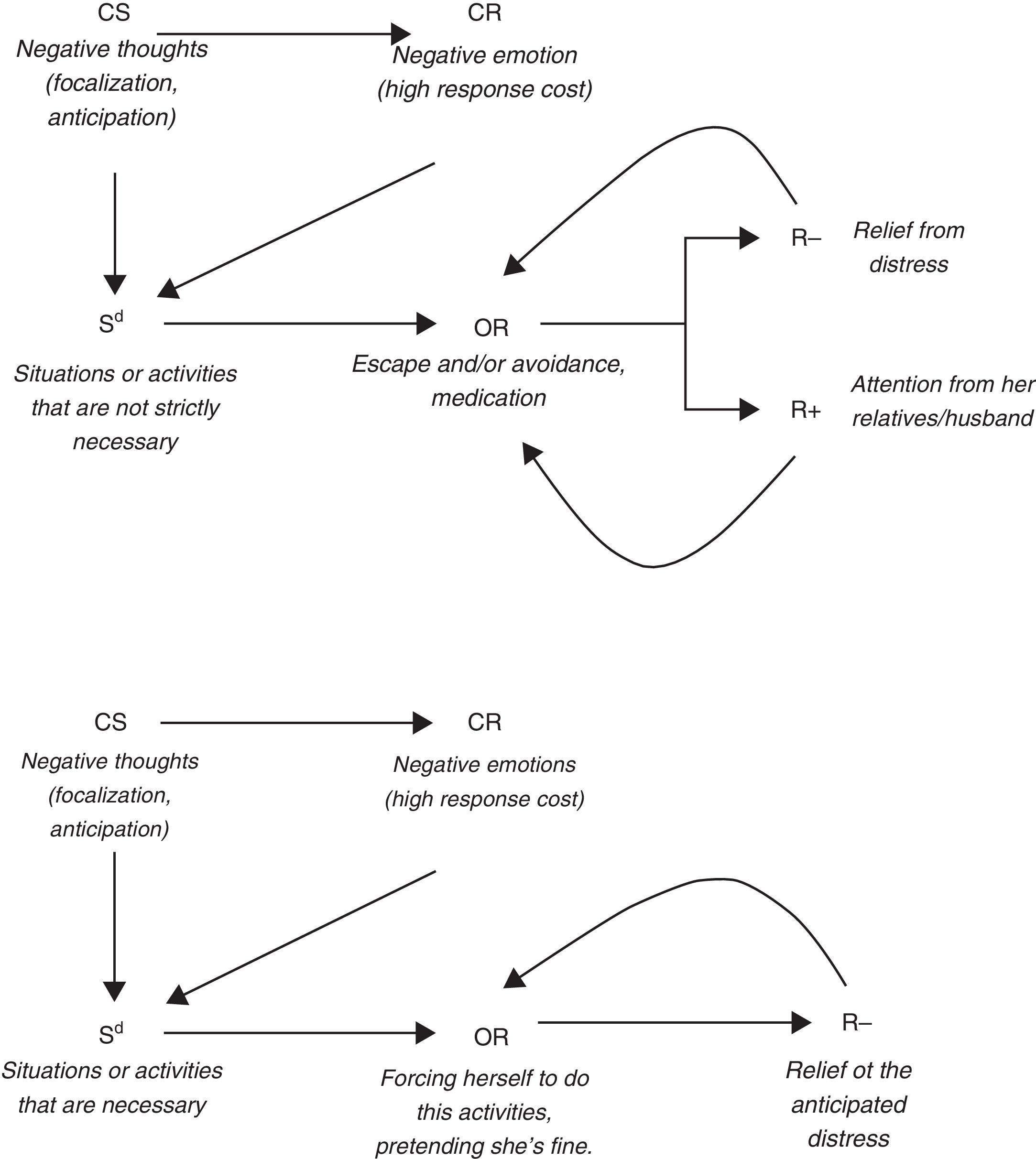

In light of these variables and analyzing the evolution of the problem, we could say that, in her life, E. has gone through certain moments or episodes in which her mood has been very low (“depressed”), and her anxiety has risen. These moments have most always been related to some negative circumstance that appeared in a given area of her life, and with which E. did not adequately cope. In fact, she started avoiding things as a coping mechanism, not going out, staying in bed, trying to shelter herself in her social “safety net” (her family and husband), avoiding problematic contexts (by, for example, asking for a sick leave), going to see a psychiatrist and starting on medication, etc. E. also resorted to psychological therapy, but never actually finished any of the treatments she started, abandoning them instead in the moment in which she was told she had to implement some changes in her behavior that required effort and/or facing her difficulties (once again showing her penchant for avoidance). These problems were solved by time, with help from medication and favorable changes in her circumstances; this taught E. to keep a stable mood if and when her circumstances were favorable, without learning to deal with problematic situations. Hence, when something became negative or suffered any kind of unexpected change that she did not particularly like, E. fell on a very negative, distorted speech that, instead of helping her, contributed to make the problem worse. These verbalizations generated intense negative emotions, which interfered with her performance in her job and her social and personal life. This speech was characterized by constant doubt and fears about everything she does and about even the most day-to-day situation (like going to the grocery), focusing on, anticipating, and maximizing the negative in relation with things that were going to happen and how others will behave with her (some of which are derived from the rule “everyone wants to hurt me”), thoughts of guilt regarding the suffering she causes to those that love her, anticipations of another depressive episode, and the constant search for explanations about why she feels bad. Some suicidal thoughts were briefly mentioned, although they seemed to not mean a serious problem upon close inspection.

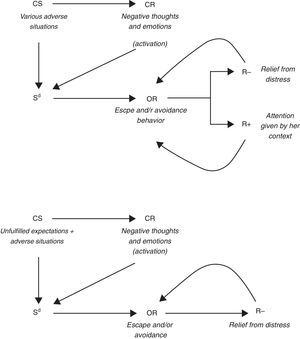

In difficult moments, she resorted to help and support from her family and husband, who reassured her and helped her in her difficulties, while devoting great amounts of attention to her. As soon as things improved or got better, so did her mood, experiencing an increase in her will to do things and setting targets that she could not reach while she was not feeling well. However, little by little these new self-imposed pressures started to overwhelm her (because the targets she set for herself were too demanding). This, together with her chaotic way of programming her schedule and her lack of tolerance of reinforcement delay, meant that she had great difficulty to undertake and persist in the tasks she set for herself, thus changing her targets and chores without really finishing anything and, therefore, not being able to see the results of her efforts. This led her to again doubt herself, her skills, and to focus her attention on negative aspects of the situation. All this could combine at any moment should anything go wrong in her life, setting the foundation for the recurrence of her problem. See Figure 1 for a graphic summary of the origin hypothesis for E.’s problem.

The dispositional role played in this process by the medication that E. had been prescribed is worth considering: despite whatever positive effect they might have had, the fact that as a side effect E. gained weight was very aversive for her. The rest of the side effects were also very hard for her (lack of reflexes, difficulty in focusing on tasks, feeling “drowsy” or “emotionally plain”, etc.). Given this, every time she recovered from her problems she tried to lose weight on her own without medical advice (eating less, resorting to laxatives, etc.). Shortly after starting this process, there is a moment in which she considers that she has lost too much weight, and she does not want to lose anymore. These moments usually happen when her mood is, again, low. Therefore, her low weight is an additional problem for several reasons: she starts worrying about what will people think about her image (fearing they will think she's sick or has an eating disorder), that combines with the bodily disarrangements that stem from depressive/anxious states (that affect her digestive system and make it hard for her to gain back her weight) and the negative incidence of the physical consequences of a low weight in her mood (lack of energy, etc.)

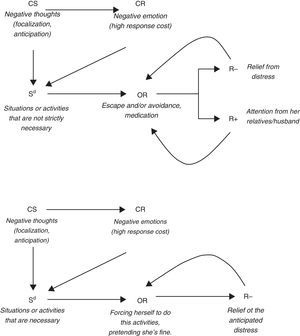

Regarding the maintenance of the problem (see Figure 2), we have to again allude to the fact that, when E. does not feel well, she starts focusing on the negative side of everything. This inner speech affects her mood and she finds it harder and harder to go out and do anything. She, in that moment, starts feeling “obligated” to do things and “pretends she's right”, all the time anticipating that she is not going to have fun, that people will notice and think ill of her, that they are going to ask her and she's going to be forced to give explanations, etc. All of this means she will start avoiding these situations, and thus giving up on potential reinforcement sources; or, in the event that she actually goes out, she always does so predisposed to focus on negative aspects, which means she will, in fact, not have a good time and hence confirming her prognostic. This makes it likelier for her to stay at home or, if she goes out, to anticipate she will not have a good time, thus conditioning social situations as more and more aversive.

Faced with situations that she deems too costly or aversive (because she anticipates she will be uncomfortable or not proficient enough, or because they generate uncertainty in her if they are new situations or decisions to make), she also tries to avoid them (by taking a sick leave or asking for others to do things for her) or faces them feeling very distressed (with constant negative verbalizations about the situation and her behavior). This avoidance is maintained through a process of negative reinforcement, but also of positive reinforcement, since she receives support and attention from her husband and family. This pattern, however, makes it difficult for E. to actually develop more adequate coping skills by herself, thus maintaining the problem. And given this lack of coping skills, the problem keeps on getting worse until she decides to go see a psychiatrist and receive some medication, which, again, has the negative effects we have previously mentioned.

Therapeutic Targets and Intervention TechniquesThe targets were essentially the same throughout all 3 treatments that progressed enough to formulate them, with all due adaptations to the specific circumstances of E. in each instance. This supports the idea that, rather than a series of different problems, we are treating the same problem manifested over and over, with the same functional analysis, and derived from inadequate or non-existent coping skills.

- •

Mood improvement. This was considered to be a transversal target as much as a requisite for all other targets to be achieved. Given the lack of pleasurable activities in which E. participated, it was considered essential to help her start some leisure habits through the planning of pleasurable activities, not only in order to raise her mood, but also because hobbies could have a protective effect against hypothetical reappearances of the problem. Besides this, attention was devoted to the reducing and modifying of her negative utterances (distortions, negative bias, exaggerations, erroneous inferences, maladaptive rules, etc.), and to the elimination of her constant complaints that only served to make her more distressed through the social reinforcement of these complaints. This was approached by using instructions in session, training E. so she was able to stop her thoughts in relevant circumstances, Cognitive Restructuring in-session, and training her in using debate strategies so she could put her invasive thoughts through reality checks.

- •

Providing E. with adequate coping skills for difficult situations, in order for her to be able to control her anxiety and prevent future episodes. To do that, problematic situations were evaluated (going back to work, driving her car, having conversations, etc.) and procedures of exposition were put to use, with the support of different coping strategies (reduced activation techniques such as progressive muscular relaxation, self-instructions that discriminated pro-therapeutic behaviors, self-reinforcement, specific instructions to face questions and remarks made by others, gradual expositions to her car and her workplace, etc.) and covert procedures when they were considered necessary so as to de-condition the situation and make her performance easier. Some of the techniques used in order to achieve this target were used too for the previous one: learning to question her own irrational thoughts and ideas and substitute them for other, more adaptive thoughts, that would in turn discriminate better adjusted behavior (through the use of cognitive restructuring) and stopping all ruminations and anticipations that favored her distress and made her interact worse with people and situations (through thought-stop techniques). She was also trained in decision-making and problem-solving so as to improve her confidence in her ability to face difficult situations without help from her environment.

- •

Giving medication up. Although it was not a target in and of itself in any of the different treatments, it was desirable in the sense that, should E. develop her own coping skills, she would have to use these skills as a first reaction to difficult situations, instead of medication, if the problem reappeared.

This phase begins with the explanation of the functional analysis and the treatment plan. E. is positively sure that her problem has been caused by her job, and the therapist makes a great effort for her to understand that, even though her job had precipitated her current situation, the problem goes beyond this and includes her general way to react to anxiety-inducing situations. As evidence for this, the therapist cites the reasons she gave for going to therapy in all previous instances, as well as the situations that she sees as complicated. Much like happened in the assessment phase, E. asks the therapist to e-mail her with the tasks she should perform, saying she has trouble remembering things. Throughout all the treatment, but especially at the beginning, she often says that she doesn’t understand why this is happening to her. Initially, the therapist repeats the relevant part of her functional analysis to her, and even e-mails it to her. Later, when the treatment has progressed, he limits himself to stopping the dialogue and asking E. to make an effort and answer herself. The answers given by E. are more and more close to the truth as the treatment progresses.

Very often, E. complains when the therapist tells her about the tasks she must do. She alludes to the high cost or difficulty those tasks mean (even when they are quite simple), and takes a long time before actually starting to use strategies like thought-stopping or finding time to enjoy herself, a pattern of behavior that also took place in the previous treatments.

Since E. does not have any hobby or engage in any activity for the sole pleasure of it, including these in her life is very important: she devotes all her free time to cleaning, ironing, and other home chores, or (most often) she takes home part of her work and spends her evenings working at home. This means that, should anything go wrong or any problem present itself in her workplace, she spends all her day thinking about it and has no effective way to distract herself, hence aversively conditioning other places (like some parts of her home) and keeping her speech tightly tied around her problems in her workplace. This is the way the therapist often emphasizes how important it is for her to find hobbies she can enjoy daily, or activities that would distract her and help her enjoy life. She initially shows great opposition to this measure, saying it is “worthless” and “wouldn’t help at all” because she “simply can’t think of anything to do”. The therapist, as a supporting measure, and having previously agreed with E. to do so, sends a co-therapist to her home between sessions 9 and 10 with instructions to help E. cook something new, something that the client had thought would be “fun”. However, the experience proves to be very unpleasant for E., who says the co-therapist had “made her feel bad” because she (the co-therapist) “had done a lot of things in her lifetime” and E. had not. It is in this moment that E.’s opposition to the treatment reaches its highest point. She expresses both verbally and paraverbally a lack of confidence in the strategies that she is told to use, although she continues to express her confidence in the therapist and the process. The therapist answers this by specifying what would happen should E. leave the treatment, and highlighting the uselessness of trusting the therapist but not the strategies he proposes. E. reacts by crying, but this session proves to be a turning point in the treatment. From this moment on, E. starts following the therapist's instructions more frequently and, hence, she starts seeing results. Her verbalizations are more adaptive and changes can be seen even in the way she dresses, acts, and speaks more energetic and active.

In the 13th session, E. says she is going to have to go back to work, because her sick leave has ended. Here the therapist verbally anticipates the possible difficulties she would face coming back to her workplace, and instructs her to go visit it before, in order to be exposed to the stimular complex that evokes her anxiety and stat controlling it before having to go back to work. In the end, E.’s re-incorporation to her job is less problematic than was expected, aside from the logical tensions that are normal when coming back to her job after months of sick leave. The therapy starts focusing from that moment in the relationship between E. and her coworkers, and in trying to help E. work less time at home and finding hobbies for her.

The clinical targets are considered to be achieved in session 19. Sessions 20 to 24 are follow-up sessions.

Follow-up PhaseIn this part of the treatment, the therapist focuses on trying for E. to generalize all she has learnt to other problems that may arise in the future. To do this, he allows E. to again complain in session – for about anything other than the first problems of which she complained when the therapy started –, steering her speech towards she herself finding possible ways to solve them, while verbally reinforcing any sign of generalization. Besides this, the therapist tries to evoke the emission of verbalizations by E. that adequately describe, in functional terms, the problems she might have.

In the 24th session, the case is considered to be in remission and the pharmacological therapy is starting to be interrupted.

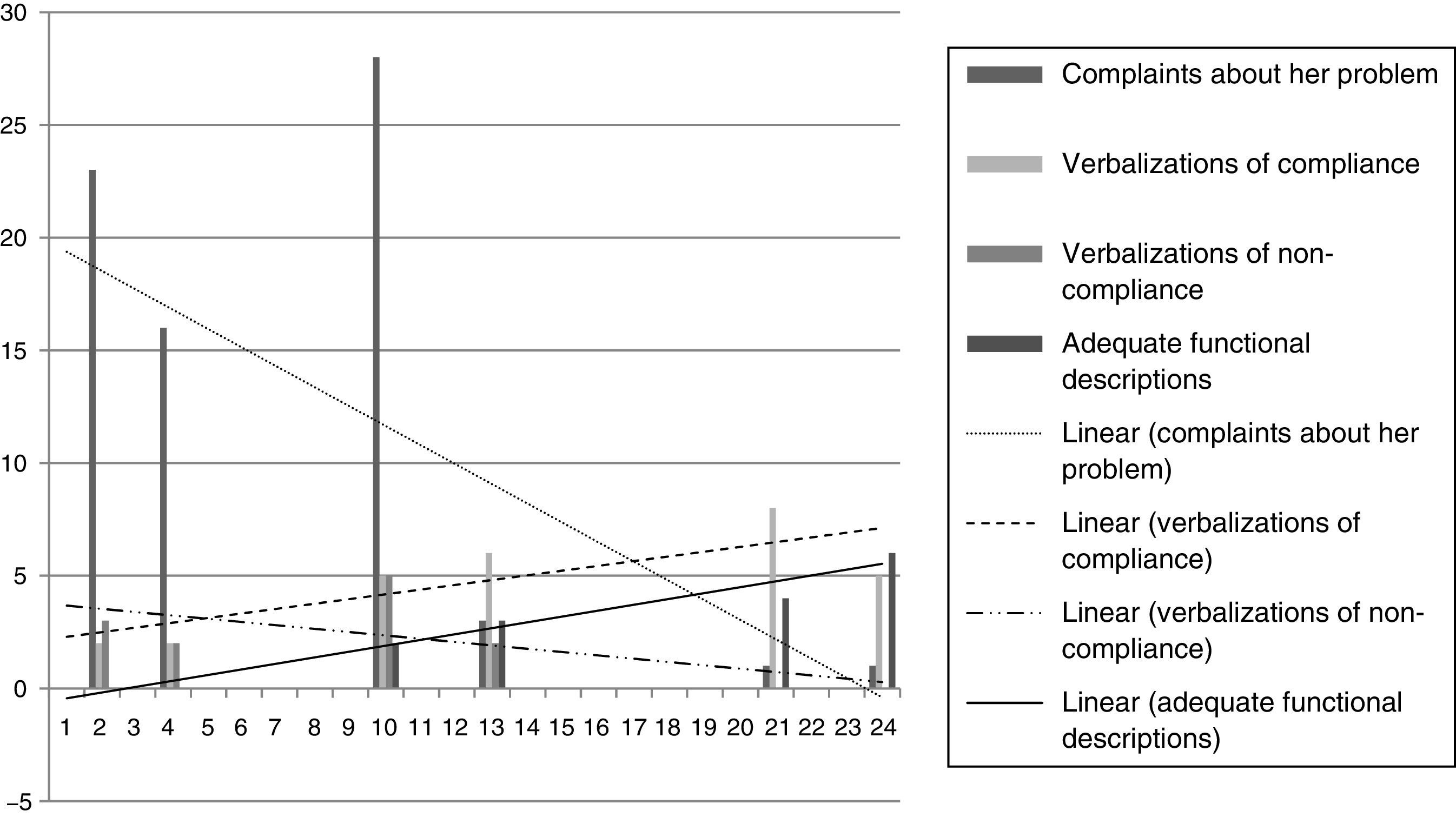

Objective Signs of ChangeEach and every clinical session with E. was recorded with a closed-circuit video recording system, after she gave her consent. All records were stored in compliance with the data protection laws.

Two randomly selected sessions from each of the three phases (assessment, treatment, follow-up) were studied. Some objective signs of change were selected:

- •

Percentage of the session in wich E. cries. E. cried frequently in the first sessions and got emotional easily throughout the treatment. Only the time she spent crying about her problems (and not about how happy she is with her husband, for example) was taken into account for this study.

- •

Compliance with instructions. Both her description of having followed the therapist's instructions and her verbally anticipating she was going to do it were taken into account, as were her description and/or anticipation of non-compliance.

- •

Negative descriptions of her problem. Utterances by E. that include complaints of an expression of despair or lack of confidence in her own ability to change or to experiment any improvement in the future.

- •

Functionally correct descriptions of her problem. This sign was chosen because E. often manifested she did not understand why this happened to her. We consider that it is of the utmost importance that she starts understanding and describing the functional mechanisms that govern her maladaptive behavior, since it would allow her to act in a more precise way and prevent the reoccurrence of her problems.

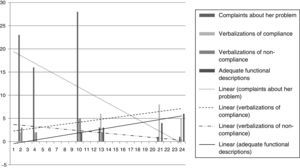

In each session, the occurrence of each of these signs was noted. In the case of crying, its duration was also registered (see Figure 3).

As can be seen in Figure 3, E. shows an objective improvement, according to the selected signs. Negative signs (non-compliance utterances and complaints about her problem) show a decreasing tendency, while positive markers (compliance utterances and correct functional descriptions) show an increasing tendency as the treatment progresses. This is coherent with what could be directly observed by interacting with the client and observing her speech and her prosody. We can say, then, that her problem is objectively in remission.

DiscussionRegarding E.’s improvement, it is obvious that it has happened, not only through the objective markers but, as was said before, through the interaction with her and the content of her utterances. Initially, E.’s behavior in session was, both verbally and para-verbally, that of a very depressed, despondent person: crying often, speaking in a hush, slumping in the chair, etc. Besides, she constantly alluded, with a great dose of drama and sorrow, how horrible she felt and how hard it was going to be for her to get better, since this had happened to her before. She verbalized a great mistrust in her own ability to feel good and a deep concern for the future that awaited her, should she prove unable to recover.

However, as soon as she started following the therapist's instructions, the content of her speech and the way she expressed started changing: the crying disappeared relatively soon, and even though her complaints were still uttered often, their content had changed from despair to a sort of indignation that proved to be way more productive and more useful in helping her change.

This progression, regarding E.’s original demands, was undoubtedly related to the techniques that were used in the treatment. However, the main concern of this paper is not to merely show E.’s improvements in terms of how her relevant behaviors were reduced or modified, but to reflect on what made E. commit to this treatment in a way in which she had not committed to the other three that were conducted by therapists from the same clinic with the same theoretical frame and the same way of working, each of whom designed their intervention plans in accordance with a very similar (if not identical) functional analysis, setting the same clinical targets and even using the same techniques and strategies. It would be rash, however, to give all credit for the client's improvement to the performance of the therapist; therefore, we have considered several hypotheses that could be possible explanations for the different degree of compliance and adherence between this last treatment and those that went before.

- •

Differences in the anxiogenic situation. The fact that the client has faced in different moments situations that have clear similarities that caused similar problems for her (anxiety responses) and evoked similar maladaptive verbalizations might constitute a learning history that allows E. to simply not be willing to let it happen again.

- •

Vital stage. In previous treatments, E. was in what could be called “transition stages” in her life (getting married and leaving her parents’ home, taking care of new children in her job, etc.), but did not carry the weight that, in this treatment, her age has added: she is now thinking about having children. She does not want to have them as long as she is still “not well” and under medication, and she is overwhelmed and pressured by the idea that “she's going to be like this forever” (an erroneous idea, but one that has been created by both the psychiatrist and the family doctor that treated E.). This new factor, the notion that, should she have children, she has to start in the near future, might have had an impact and exerted a certain pressure that made E. commit to the treatment and put more effort into following the therapist's instructions.

- •

Previous treatments. Doubtlessly, the fact that in the three previous treatments the explanation of the problem was so very similar (if not the same) to the one proposed in this treatment might have been very important. Besides, the previous therapists had explicitly anticipated to E. what would happen if she abandoned the treatment or did not follow the instructions they gave her. This anticipations proved correct in time, which may have led E. into investing more effort in the treatment, thinking that, when they speak about functional chains, therapists tend to be right. All in all, E. has learned that if she attends a therapy but does not follow the therapist's instructions, she falls in the same problem again.

A central point of our argument for the importance of the therapeutic interaction in the adherence and behavior change in this case is the comparison between the performance of the three first therapists that treated E. (Therapists 2 and 3, since Therapist 1 only treated her for one session) and the last one (Therapist 4). This comparison has been made after watching all sessions from Treatment 4 and reading the clinical files of Treatments 2 and 3, and interviewing Therapists 2 and 3. We conclude the following:

Performance of Therapists 2 and 3. Both of these therapists have a very empathetic pattern, which may have led them to play the same role as the client's family and husband: calming her, resolving her doubts, generating positive expectations of improvement, etc. This may have contributed to the maintenance of her complaints and her unchanged behavior pattern. Very often, positive consequences of committing to the therapy are anticipated, but they don’t cause the intended effect on the client. The aversive consequences of not committing to the treatment and just keep doing the same things are not anticipated as often. When E. complains, both therapists displayed empathy and understanding, and again try to focus on the positive effects of change, only very rarely choosing to extinguish the complaint itself or exposing the client to aversive stimuli. The strategies are frequently insisted upon, but punishment is seldom used. It is noteworthy that in both treatments the therapy was interrupted precisely in the moment in which, after the functional analysis was explained to E. and the clinical targets were set, concrete strategies were proposed and some effort was required. It is the moment in which the client was asked to work and start changing behaviors and verbalizations that were deeply rooted in her way of living. She started following some instructions, but got rapidly frustrated by the lack of fast progress and the inherent difficulties of changing habits. Again this made her complain and start doubting the efficacy of the techniques themselves, which could have meant that they became more costly for her to perform. The therapists might have been excessively permissive and not firm enough to correct this lack of commitment. In both cases, the treatment was interrupted by the client few sessions after the treatment phase began, without any target having been achieved. Despite this, some advances were made that were apparent in the subsequent treatments, such as changing her concept of “depression” or “anxiety” as diseases in the medical sense of the term, the importance of staying active despite sadness or trying to question her negative thoughts, etc. This may account for the fact that, despite there was an overall lack of changes, the client still gave a chance to psychological treatments, even in the same clinic.

Performance of Therapist 4. In spite of the logical similitude between Therapist 4 and Therapists 2 and 3, there are some differences in his way of interacting with E. that are worth discussing:

- •

Differential reinforcement of complaint throughout the treatment. Even though in normal circumstances the therapist would not reinforce complaints (except in the assessment phase or if he wanted to evaluate the progress), in this case and considering that one of the objectives of the treatment was to ensure that the client would commit to it, the therapist reinforced (with attention, questions that showed interest, etc.) E.’s complaints until the treatment had progressed quite a lot, with the intention of favoring her adherence. In this way, he wanted to prevent E. from feeling judged or uncomfortable in any way for expressing thing that, in her context, are always met with attention and affection. This reinforcement was, logically, slowly diminished in intensity and frequency and, from a given moment in the treatment, E. was asked to tell one good thing for each bad thing she told, which the therapist used to differentially reinforce positive verbalizations. This gradual change in intensity and frequency of the reinforcer might have made a difference.

- •

Interaction style. In purely paraverbal terms, Therapist 4's style is much more “reserved” than that of Therapists 2 and 3. This means he doesn’t smile as often and makes a great effort to be emotionally neutral in his expression in the initial sessions of the treatment, in order for his smile to not lose its potential power as social reinforcer due to habituation.

- •

Normalization. E. is constantly describing herself as “weird” or somehow “inferior”, which makes her suffer greatly. Therapist 4 makes great efforts to explain to her, time and again, that there is nothing weird in her, that she functions just like everyone else and it was her circumstances that made it almost inevitable for her to face this situation. This has a calming effect in E., who also starts saying more frequently that what happened to her was a consequence of her circumstances, instead of her being “crazy” or “somehow wrong”, as she said often in the beginning of the treatment. This redirecting of her attention to her context and how to interact with it has led her to follow the therapist's instructions more often, with the positive effects that were to be expected, as well as her interest in the therapy growing.

- •

Directiveness. A common factor to all behavior therapists is that they are, in theory, directive. Far from meaning they are rigid or somehow curt in their manners, this simply means they direct the client's behavior in an active way, reinforcing or punishing utterances attending to whether they are pro- or anti-therapeutic. In this case, besides, Therapist 4 made it a point of responding by issuing aversive verbalizations when the client engaged in anti-therapeutic behavior, displaying as well severe facial expressions and prosody (for example, he did this when the client complained about the co-therapist, trying to make E. see that it wasn’t the co-therapist that had made her feel bad, but her own descriptions of the situation). Being unequivocally aversive in certain circumstances favors the discriminative power of the therapist, and the differential and comparatively sparse use of appetitive utterances prevents the client from habituating to any verbal behavior the therapist might use. Besides, if we conceptualize the clinical process as a verbal shaping, this would be coherent with the results that show that this shaping is more effective if the therapist not only reinforces pro-therapeutic utterances, but also punishes anti-therapeutic verbalizations (Calero-Elvira, Froján-Parga, Ruiz-Sancho, & Alpañés-Freitag, 2013).

- •

Anticipation of contingencies. Playing a fundamental role in the client's motivation for therapy, the anticipation of contingencies might be very relevant to the following of instructions and adherence to the treatment (de Pascual, 2015). The therapist intentionally emphasized the consequences (positive and negative) that E.’s behavior would have on her problem. This means that, when he explained or proposed a particular strategy or homework assignment for the client, the therapist frequently alluded to the apetitive effect it would have on her problem (for example, “if you practice relaxation often, you will control your anxiety more easily”) and to the possible difficulties she might face (for example: “the first time you get into your car again you will not feel good but if you stay inside and follow my instructions, you will find you will start feeling better faster than you expect”). He also emphasized the long-term effects of the treatment (“if you keep it up, you’ll see you are going to feel great very soon”). Quite relevantly, he also used the exact same sentences many times when describing the problem and the processes that explained it, with the (successful) intention of them becoming something the client would in time use. A good example could be “the only way for you to fall in this again, is for you to keep acting the same way”, something the therapist said every time the client complained or expressed her doubts or fear of “falling in this” again. This uniform and repeated use made the client start saying this to herself and, most importantly, using it as an answer when people close to her asked her about how she thought she was going to be in the future. However, positive consequences were not the only ones that were anticipated; in the moments in which E. verbalized doubts about following instructions or even abandoning the treatment, the therapist explicitly anticipated what was most likely to happen. For example, when the client expressed her doubts about finding hobbies and alluding to a fear she had previously expressed, the therapist said: “it's up to you, you have two options: either you find things that you enjoy doing just for the sake of doing them and you invest time in them, which will protect you in the future, or you keep devoting all your time to your job, in and out of the school, and you become that sad, grey woman you are so afraid of becoming, a woman about which one can only say that she's sad because there is nothing else to say”. This dichotomy, this anticipation of apetitive and aversive consequences, might have contributed to E. starting to anticipate in a more accurate way the consequences of her own behavior, including her behavior of following a treatment and actively working for the change in her life. The therapist tries to evoke every now and then the emission of functionally correct anticipations or descriptions of her problem by the client, something that, as was apparent in the results shown, he managed to achieve. This can also be relevant regarding her commitment to the treatment.

- •

Gender of the therapist: although this factor cannot be purely considered to be related to his “performance”, it must be taken into account when trying to propose possible explanations for the difference in the treatments’ results. Therapists 1, 2 and 3 are female, while Therapist 4 is a male. The client's closest persons, those who have taken care of her more often, are both male (her father and, later, her husband), which might have had an impact on how Therapist 4 was perceived from the beginning.

In summary, we consider the difference in adherence to the treatment and the various therapists’ instructions can be explained by the influence of several factors like the reoccurrence of the anxiety-depression episodes, specific circumstances that might have motivated the client to change, and the learning processes that took place during the previous treatments, with the differences in interactive style between therapists being a very important factor. This last point makes us consider that maybe, when trying to favor the following of instructions, motivation, and adherence to treatment, it is important for the therapist to be very careful about how he or she issues reinforcements (smiles, attention, etc.) and verbal aversive stimulation, in order for he or she to not lose his/her potential strength as a control element regarding the client's behavior. This must not be interpreted as a recommendation for all therapists to be curt or sullen in their interaction; they simply must pay attention to the client not being satiated or habituated to the reinforcers that the therapists are using. Lastly, and very importantly, we think that the therapist must strive to explicitly anticipate what the consequences of the client's behavior will be, both aversive and appetitive. In this way, we will not only be treating a problem: we will be teaching the client to anticipate the results of their own behavior.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.