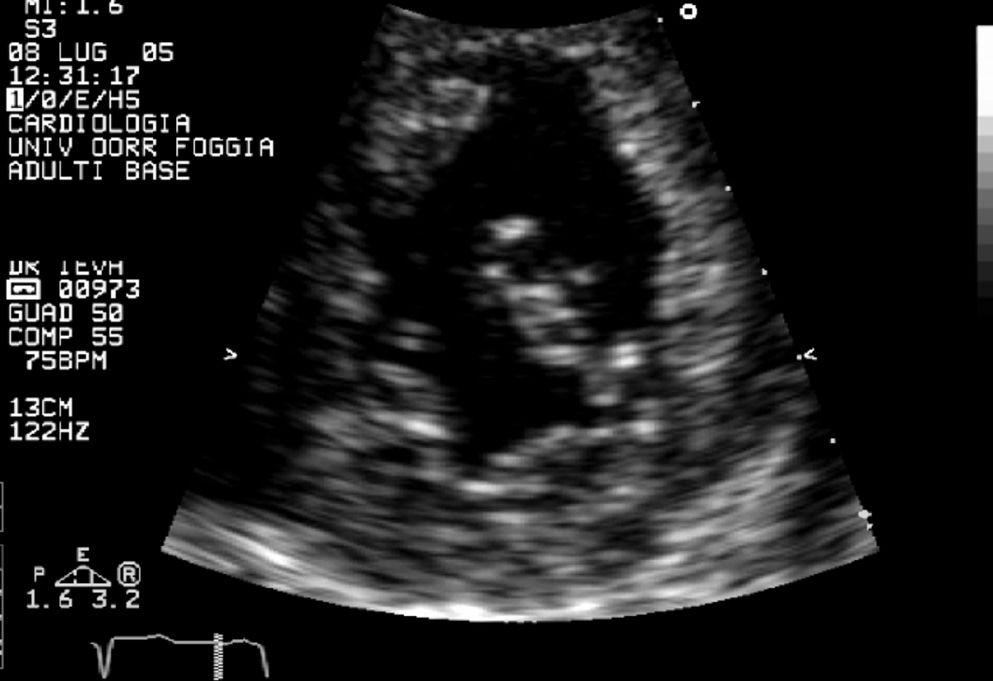

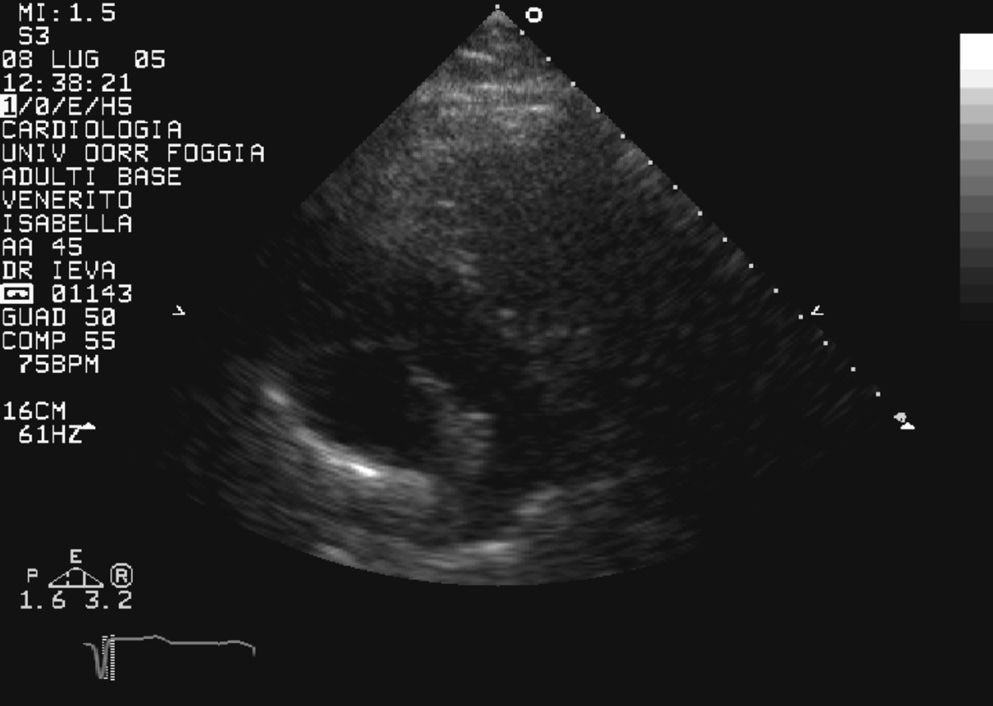

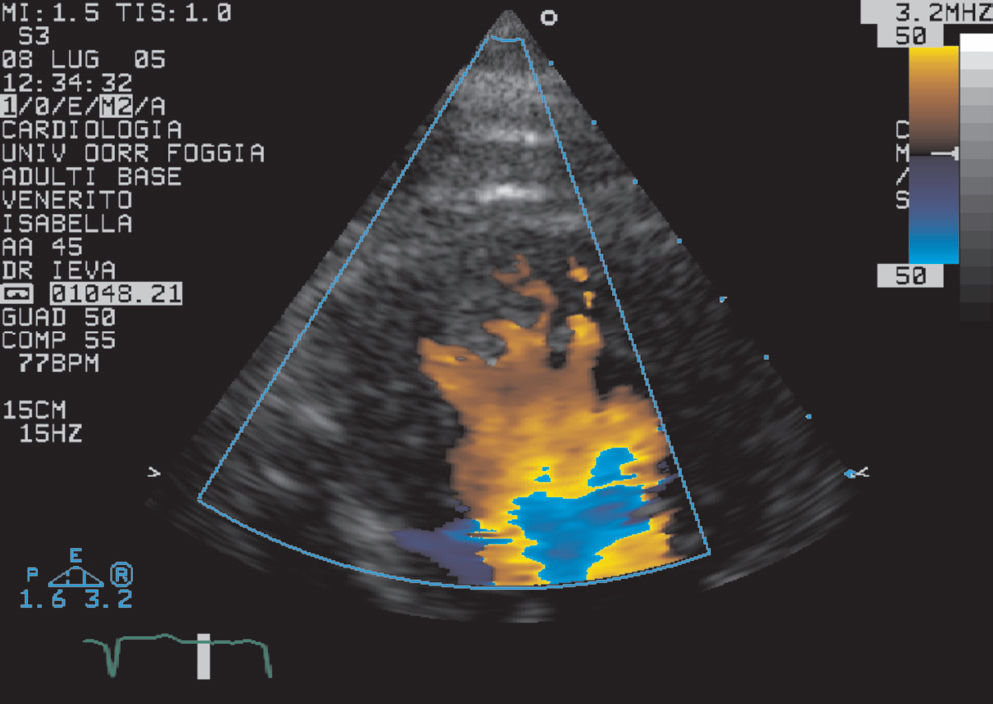

A 65-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and a prior diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was admitted to the Department of Cardiology for palpitations. Cardiac examination revealed a 3/6 holosystolic murmur over the left parasternal area. Echocardiography showed that the aorta extended from the morphological systemic ventricle (RV), which was identified by the three-leaflet tricuspid valve (Fig. 1) that was inserted more apically than the mitral valve (Fig. 2). The pulmonary trunk, identified by its bifurcation, arose from the morphological “pulmonic” ventricle (LV) (Fig. 3). The RV was mildly dilated, the septum wall was 18 mm thick, and systolic RV function was mildly reduced (ejection fraction 40%). There was moderate atrioventricular (tricuspid) valve regurgitation. The LV showed normal function and there was mild atrioventricular (mitral) valve regurgitation. There was mild aortic regurgitation but no pulmonary valvular stenosis. A persistent patency of oval-shaped foramen was found. The aorta was anterior and to the left of the pulmonary trunk, and the two vessels were side by side. Holter monitoring demonstrated incessant tachycardia with only brief periods of sinus rhythm. The patient was submitted to electrophysiological evaluation, and the accessory pathway was successfully ablated using radiofrequency pulses.

Apical four-chamber view shows dilatation of both the left atrium and left appendage and a smooth interventricular septalright surface against the trabeculated septal left surface in the correct position (normal atrial situs). This permits diagnosis of ventricular inversion and the presence of a three-leaflet tricuspid valve inserted more apically than the mitral valve

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA) is a rare form of congenital heart disease, first described by Von Rokitansky in 1875.1 It accounts for < 1% of all forms of congenital heart disease. In this anomaly, the right atrium enters the morphological LV, which gives rise to the pulmonary artery, and the left atrium connects with the morphological RV, which gives rise to the aorta. Thus, AV and ventriculoarterial discordance exists, and although blood flows in the normal direction, it passes through the “wrong” ventricular chamber. In addition, the aorta is usually, but not always, anterior and to the left, and the great arteries may be side by side. Because the tricuspid valve always enters a morphological RV, it also lies on the left side in the systemic circulation and is more appropriately termed the systemic AV valve.2 Thus, the LV supplies pulmonary circulation and the RV supports systemic circulation.

CCTGA usually is associated with a severely reduced life expectancy due to ventricular septal defects (74%), pulmonary valvar stenosis (74%), systemic (tricuspid) valve abnormalities (38%), and complete heart block (5%). Only 1–10% of individuals with CCTGA have no associated defects.3 Patients with CCTGA are increasingly subject to cardiac heart failure (CHF) with advancing age; this complication is extremely common by the fourth and fifth decades. Tricuspid (systemic atrioventricular) valvular regurgitation is strongly associated with RV dysfunction and CHF.4 Life expectancy is limited by the onset of systemic (morphologically right) ventricular failure.5 Although long-term survival is possible, it is exceptional and tends to occur in those patients without associated abnormalities and in whom no operation has been undertaken.6

Primary diagnosis of CCTGA in adulthood using echocardiography can sometimes be missed, especially if this rare condition is not suspected. This is probably due to similarities between some echocardiographic features of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and the features due to other cardiomyopathies. Differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, prominent normal myocardial trabeculations, cardiac tumors, and left ventricular apical thrombus.

In the present patient, after previous echocardiographic examinations, a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was diagnosed that involved primarily the interventricular septum and free wall, with relative sparing of the posterior wall. At the time of our examination, we excluded trabeculae and intertrabecular recesses, which are typically absent in this idiopathic heart muscle condition. The prominent trabeculations were of the same echogenicity as the surrounding myocardium, despite the fact that apical thrombi showed different echogenicity from the surrounding myocardium.7 In addition, they were localized to apical segments of the ventricle, despite prominent normal myocardial trabeculations, which are rarely located in the apical region.8 It would have been possible to diagnose isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium based on the fact that color flow imaging showed forward and reverse flows between prominent trabeculations during the cardiac cycle (Fig. 4). However, the position of the three-leaflet tricuspid valve, which was inserted more apically than the mitral valve, and particularly the atrioventricular and ventriculoarterial discordance indicated a diagnosis of congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA). In this congenital cardiopathy, the systemic ventricle (RV) shows both prominent trabeculae and septomarginal trabeculations (“septal band”), which is consistent with what was observed in the present case.

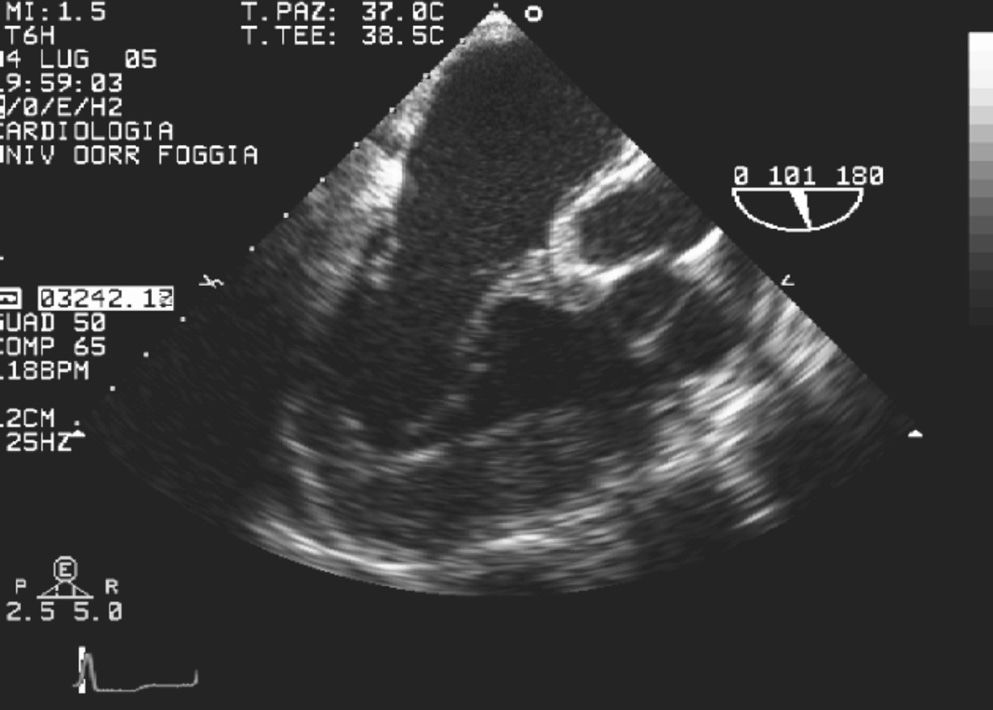

Prominent myocardial trabeculations can also be recognized in dilated cardiomyopathy, but to a lesser extent than in CCTGA. The transesophageal examination, which directly evaluated the morphological features of the appendage (Fig. 5), correctly determined atrial situs. Moreover, the mid-esophageal view showed the discontinuity between the aortic valve and the systemic atrioventricular valve because of the muscle interposition (Fig. 6); transthoracic view failed to reveal this discontinuity.

Previous authors9 suggested that two-dimensional echocardiography, combined with color-flow Doppler imaging, might provide sufficient information to arrive at the correct diagnosis of this cardiac malformation and its associated anomalies. However, we think that in some adult cases, transthoracic and transesophageal approaches should be integrated. As shown in the present case of echocardiographic visualization of severe ventricular hypertrophy and prominent trabeculations, examination of the ventriculoarterial and atrioventricular connections may be necessary. As a result of the impressive success of pediatric cardiac care, the number of adult patients with congenital heart disease is now greater than the number of pediatric cases. Therefore it is important for echocardiographers to learn about this congenital heart defect in order to avoid diagnostic mistakes.