Dear Editor,

Quinolones were first introduced in 1962, and their excellent oral absorption, good tissue distribution in tissue, and urinary concentrations, which exceed the minimum inhibitory concentration for many common pathogens, popularized their use in routine clinical practice. Structural modifications of quinolones resulted in improved pharmacokinetics, with a longer elimination half-life, which permitted once-daily dosing and improved tissue penetration. For this reason and many others, fourth generation compounds, such as moxifloxacin, are increasingly being prescribed (1,2).

Moxifloxacin is licensed to treat acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, community acquired pneumonia, complicated and uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections, and complicated intra-abdominal infections. In 2007, moxifloxacin ranked 140th among the top 200 drugs prescribed in the United States, and it has proven to be a blockbuster drug, generating billions of dollars in revenue. In 2007 alone, Avelox® generated $697.3 million in sales worldwide (2).

In ophthalmology, moxifloxacin is widely prescribed as eye drops to treat infectious keratitis and as a postoperative prophylactic regimen during cataract surgery. It is also injected intraocularly to prevent and treat intraocular infections (3).

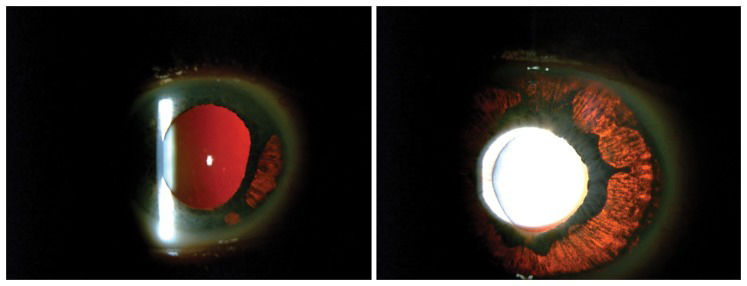

Acute depigmentation of the iris is a new clinical condition that is characterized by an acute onset of pigment dispersion in the anterior chamber, depigmentation and discoloration of the iris stroma, pigment deposition in the anterior chamber angle, and positive transillumination (4). Systemic moxifloxacin treatment has been associated with this condition (5).

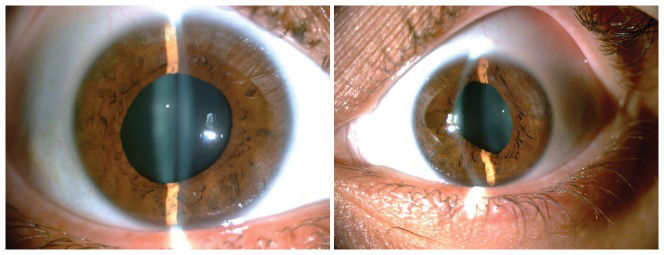

Several types of iris changes, such as positive transillumination, dyschoria, and depigmentation, have been reported; anterior chamber reaction and anterior uveitis-like syndrome have also been observed in some cases. Patients usually have bilateral asymmetrical involvement. Atonic pupils with distorted margins and occasionally ocular hypertension were described by Tugal-Tutkun et al. (4,5).

This assemblage of clinical findings is distinct from other known causes of iris depigmentation and pigment dispersion, such as Fuchs' uveitis syndrome, viral iridocyclitis, Horner's syndrome, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, and pigment dispersion syndrome (4,6,7,8).

Acute depigmentation of the iris may be more common than expected in many countries, including Brazil. Therefore, it is important to detect and correctly diagnose it. Below, we describe three recent cases of acute depigmentation of the iris.

THMZ, a 70-year-old white female with diabetes and hypothyroidism, presented with photophobia for 15 days. Her eyes were examined twice in the previous 2 years and found normal. A current exam revealed best corrected visual acuity of 20/20 OU. The IOP was 14 mmHg OU. Anterior biomicroscopy showed positive iris transillumination in both eyes and a heavily pigmented anterior chamber angle. No anterior chamber reaction or signs of inflammation were noted. The lens was clear OU. The fundoscopic findings were unremarkable. The patient had been prescribed a 15-day course of systemic moxifloxacin (Avalox®) for pneumonia 3 months before the onset of symptoms.

TF, a 32-year-old white female complained of low visual acuity and photophobia in the left eye for 10 weeks and the right eye for 8 weeks. The exam revealed visual acuity of 20/20 OU. Biomicroscopy showed bilateral positive iris transillumination, dense atrophy, and dyschoria. The lens was clear OU. The IOP was 16 mmHg OU, and the fundoscopic findings were normal. No signs of active ocular inflammation were noted. The patient had been extensively examined for uveitis and pigmentary glaucoma, with negative results. She had been prescribed systemic moxifloxacin (Avalox®) for pneumonia 2 months before the onset of symptoms.

RMP, a 26-year-old male, also had a previous history of systemic moxifloxacin use for upper respiratory infection 3 months before the onset of symptoms. An exam revealed visual acuity of 20/20 OD and 20/30 OS. Biomicroscopy showed a normal right eye, positive transillumination and dyschoria in the left eye, and a moderate anterior chamber reaction. The lens was clear OU. The IOP was 12 mmHg OU, and the fundoscopic evaluation was normal. No keratic precipitates were noted, and the condition was resolved with a short course of mild steroids.

Our cases indicated that these Brazilian patients had unilateral or bilateral asymmetrical involvement, transillumination defects, and dyschoria. Photophobia was the main complaint. The first two patients were examined after complaining of photophobia. We presume that iris transillumination was already present, although we do not know whether the patients had prior inflammation signs. The third patient was observed earlier in the course of the disease, and signs of mild inflammation were observed. All patients were treated with mild topical steroids, and their symptoms improved, although the clinical signs remained stable.

The differential diagnosis involves inflammatory and non-inflammatory entities; in most cases, the etiology and physiopathology mechanisms leading to the iris changes are unclear. Herpetic iridocyclitis without associated keratitis is a distinct entity that is characterized by unilateral recurrences in the same eye, sectoral or patchy atrophy of the iris, and an acute IOP increase (4). Sectoral iris atrophy is rarely observed in immunocompetent patients with CMV anterior uveitis. Sectoral atrophy resulting from ischemic necrosis of the iris and loss of function of the sphincter muscle may cause pupillary distortion, which is sometimes associated with iris spiraling. Transillumination caused by the loss of iris pigment epithelium may be observed in the absence of apparent iris stromal atrophy. Posterior synechiae develop in more than 50% of cases (5).

Fuchs' uveitis syndrome is another unilateral uveitic entity that is associated with diffuse atrophy of the iris with or without heterochromia. One of the early diagnostic features is iris stromal smoothing, with loss of the normal corrugated texture. Iris stroma does not assume a granular appearance in Fuchs' uveitis syndrome, and atrophy, with or without hypochromia, is diffuse (6,7).

The pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin demonstrate that the aqueous concentration is higher than the vitreous concentration upon topical administration. However, the aqueous concentration is similar to that in the vitreous when moxifloxacin is taken orally. Knape et al. observed that only phakic patients have been reported with acute depigmentation of the iris associated with moxifloxacin, most likely because the posterior-to-anterior clearance may be impaired or perhaps posterior synechiae trap the drug in the posterior chamber. This explanation might be the reason why only systemic and not topical moxifloxacin causes this condition (9).

All physicians, not just ophthalmologists, should be aware of this entity. The potential associations should be better understood because it is still unclear whether this disease represents an adverse effect of fluoroquinolone use or the sequelae of a systemic infectious disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONSNascimento HM wrote the manuscript and collected the data. Sousa JM wrote the manuscript. Campos M collected and revised the data. Belfort Jr collected the data and revised the final draft.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.